Implementation frameworks and quality improvement initiatives emphasize the importance of supervision and feedback in advancing practitioners’ use of evidence-based practices (EBPs) in community mental health services (

1–

5). Appropriate supervision improves practitioners’ views about EBPs, increases fidelity of EBP implementation, and assists with the adaptation of EBPs to specific client problems, populations, or settings (

6–

10). However, a supervisor’s leadership behavior may play a key role in influencing practitioners’ attitudes toward receiving supervisory feedback to support EBP delivery (

11,

12).

Feedback is an important component of efforts to improve quality of care (

13). A growing body of research is investigating how targeted, ongoing feedback that is relevant to practitioner needs can be used to improve the implementation of EBPs (

2,

4,

14–

16). For example, audit and feedback interventions can improve implementation by highlighting discrepancies between practitioners’ current practice and their target performance and creating an action plan for improvement (

17,

18). Inherent in these interventions is the assumption that practitioners are open to feedback, but individual attitudes toward feedback may vary. Supervisory leadership behavior may influence practitioners’ willingness to seek out feedback and to apply it when it is given (

19,

20).

Transformational leadership theory and leader-member exchange (LMX) theory, two of the most influential theories in the business and management literatures, describe how leadership affects team and employee performance (

21). The full range leadership model developed by Bass and Avolio (

22) identified several dimensions of leadership behaviors, with the transactional and transformational styles being the most effective and well-researched. This study examined supervisor transformational leadership because of its focus on creating a vision and buy-in for strategic initiatives such the implementation of EBPs and its promising role in previous implementation studies (

12). Transformational leaders inspire employees to follow a particular course of action by considering individual employees’ unique talents, stimulating new ways of thinking and solving problems, and creating a shared vision and sense of purpose among employees (

22,

23). Transformational leadership has been shown to have a positive association with practitioners’ attitudes toward EBPs during implementation, and it has been linked to feedback-seeking behavior and use of supervision (

12,

19,

24–

28).

LMX theory focuses on the dyadic relationships between leaders and followers, and on how social exchanges create and sustain the quality of such relationships (

29). Low- LMX relationships are based on economic exchange and characterized by formal agreements and tit-for-tat mentality (

30,

31), whereas high-LMX relationships are more social in nature and characterized by reciprocity, support, and commitment (

32–

34). Research on LMX and implementation of EBPs is limited, with the exception of a study by Aarons and Sommerfeld (

35) that found no significant association between LMX and attitudes toward EBPs. However, outside of the context of EBP implementation, research has consistently demonstrated a correlation between LMX and staff perceptions about supervision, reception to general feedback, and feedback-seeking behavior (

20,

36–

40).

Researchers have called for more integrated studies of transformational leadership and LMX on the basis of evidence that the two leadership dimensions complement and influence each other (

41–

45). For example, Wang et al. (

45) suggest that transformational leaders nurture higher-quality LMX because their charismatic appeal makes employees more receptive to interaction. Conversely, supervisor-employee interaction (i.e., LMX) may be necessary for the impact of transformational leadership to fully emerge (

42,

43,

46). Moreover, transformational leadership may be ‘personalized’ through the individual exchanges that build LMX (

45,

47).

This study examined both transformational leadership and LMX as they relate to each other and to practitioners’ attitudes toward feedback (

48,

49). We examined how transformational leadership and LMX may work together or independently to influence practitioners’ attitudes toward feedback to support EBP delivery. Despite growing evidence of the importance of feedback for EBP implementation, there has been relatively little focus on practitioner attitudes toward feedback in mental health settings. This study provides a starting point for understanding leadership-related mechanisms that may influence practitioner attitudes toward feedback and subsequent adoption and use of EBPs (

18). We conducted a multilevel path analysis using survey data from 363 mental health practitioners to examine how transformational leadership and LMX relate to one another and to practitioners’ attitudes toward feedback that supports EBP delivery.

Extending from the literature discussed earlier, the study hypotheses were as follows: transformational leadership will be positively associated with mental health practitioners’ attitudes toward feedback (hypothesis 1), LMX will be positively associated with mental health practitioners’ attitudes toward feedback (hypothesis 2), and transformational leadership will be indirectly associated with mental health practitioners’ attitudes toward feedback through LMX (hypothesis 3).

Study findings have the potential to inform leadership interventions aimed at increasing staff openness to feedback, feedback-seeking behavior, and incorporation of feedback into day-to-day service delivery. In turn, openness fostered through effective leadership may enhance clinical practice, improve EBP implementation and sustainment, and ultimately increase the quality of care provided to clients.

Methods

Participants

This study was part of a larger research project focusing on organizational issues and improving public-sector mental health care for children, adolescents, and their families through implementation of EBPs. Participants were recruited from a roster of all public-sector mental health clinics in San Diego County that received county funding for services. Eligibility criteria included provision of behavioral health services to children, adolescents, families, or some combination and at least one identified team leader or supervisor. The study focused on teams, rather than organizations, because community-based mental health service delivery is often centered on treatment teams or clinics. Teams were defined as groups of practitioners who share the same primary work supervisor and regularly interact with each other to accomplish work objectives. On the basis of administrative data, we identified 99 mental health treatment teams. One team was excluded for nonresponse despite repeated contact attempts, seven teams declined to participate, and 90 teams agreed to participate (91% team response rate). Twenty-three teams were subsequently excluded because they did not have a clearly identified supervisor. The final team sample consisted of 68 mental health teams (91% team response rate) across 18 organizations.

Of the 440 eligible staff members on those 68 teams, 435 agreed to participate (99% staff response rate). Administrative staff members (N=15) were excluded from the study, resulting in an initial sample size of 420 (

11). Data from 57 participants were excluded because participants did not provide enough information to identify their work team, resulting in a final practitioner sample size of 363 (

50). The mean±SD team size was 5.34±3.4 practitioners.

Procedure

Study approval from the appropriate institutional review boards and informed consent from practitioners were obtained before survey administration. Data were collected in 2007–2008. Trained research assistants administered the survey in paper format to participants in meetings at each program location. The survey took approximately 60 minutes to complete, and research assistants checked surveys for completeness. If participants did not finish during the allotted time, research assistants and participants agreed on a designated time (usually a week later) when the research assistant would return to collect completed surveys. Practitioners were not compensated for their participation in the survey, but light refreshments were provided during survey administration. Ethical principles as outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki were followed.

Measures

Transformational leadership.

The Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) form 5X was used to assess transformational leadership (

51). The MLQ asks respondents to indicate the extent to which their supervisor engages in specific leadership behaviors. Consistent with past research (

51,

52), transformational leadership was represented by four domains: idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration. For example, participants were asked whether their supervisor “expresses confidence that goals will be achieved.” Response options ranged from 0, not at all, to 4, to a very great extent, on a 5-point Likert scale. We computed mean transformational leadership subscale and overall scale scores, with higher scores indicating a higher level of transformational leadership. Previous research found high reliability for each domain (Cronbach’s α=0.91, 0.86, 0.94, and 0.93, respectively) (

26). The overall Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for transformational leadership in this study was 0.95.

LMX.

Scandura and Graen’s (

53) seven-item measure of LMX was used. A sample item from the LMX scale is “How would you characterize your working relationship with your supervisor?” Responses were given on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0, extremely ineffective, to 4, extremely effective. We computed a mean LMX scale score from all items, with higher scores indicating higher quality of the leader-follower relationship. Previous studies using this measure reported Cronbach’s alphas of 0.92 and 0.94 (

54,

55). The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient in this study was 0.92.

Feedback.

The feedback subscale of the Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale–50 (

11) was used to assess practitioners’ attitudes toward feedback (the most recent version of the scale can be accessed at

https://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13012-017-0573-0) (

56). The feedback subscale consists of three items asking about attitudes toward EBPs: “I enjoy getting feedback on my job performance,” “Getting feedback helps me to be a better therapist/case manager,” and “Getting supervision helps me to be a better therapist/case manager.” Participants rated the extent to which they agreed with each item, and response options ranged from 0, not at all, to 4, to a very great extent. We computed a mean feedback subscale score by using all items, with higher scores indicating a more positive attitude toward receiving feedback. Previous research indicated that these three items represent a single factor, with loadings ranging from 0.62 to 0.68 (

11). The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient in this study was 0.80.

Analysis

In preparation for data analysis, we examined all variable distributions for normality. Skew and kurtosis for study variables were assessed by dividing skew or kurtosis values by their respective standard error and evaluating the coefficient against a table of Z scores (

57). The feedback variable was negatively skewed and was logarithmically transformed (

57). However, because this transformation did not influence the findings, we retained the original variable for ease of interpretation.

On the basis of conceptual and empirical studies suggesting that transformational leadership operates at higher levels to influence the organizational context and practitioner-level outcomes, we treated transformational leadership as a team-level construct (

21,

58,

59). Similar to past studies, supervisor transformational leadership style was measured as the average transformational leadership score given by practitioners who share the same supervisor within their respective work teams (

24,

43,

50). In contrast, because LMX represents the quality of practitioners’ individual relationships with their supervisor (

53), LMX was treated as an individual-level variable (

43,

54), as was practitioners’ attitudes toward receiving feedback. To ensure the data supported team-level aggregation of transformational leadership, we computed the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and the average within-group correlation (

60,

61). The ICC suggested that variance between work teams in terms of transformational leadership was significantly different than zero (ICC=0.28, p<0.001, 95% confidence interval=0.18–0.41). The average within-group correlation for transformational leadership was 0.67, suggesting acceptable team agreement (

60). Taken together, these statistics support treatment of transformational leadership as a team-level variable.

We also examined multicollinearity between transformational leadership and LMX. The correlation between team-level transformational leadership and the individual-level LMX variable was 0.48. In addition, the variance inflation factor (1.28) indicated that both leadership variables fell well within the acceptable range of less than 10, suggesting that the two variables represented two relatively distinct constructs and could be appropriately used together in the analysis (

62).

Missing data patterns were explored prior to analysis. None of the variables had more than 5% missing values. Full information maximum likelihood estimation, which uses all available data to generate parameter estimates, was used to handle missing data.

To examine the study hypotheses, we conducted a multilevel path analysis by using Mplus, version 7 (

63). Model fit was evaluated by using the chi-square statistic, comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA;

64–

66). Practitioner level of education, job position, and job tenure were included in the model as control variables. The Sobel test for significant mediation was used to further examine the mediation effects (

67,

68).

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the sample and mean±SD scores for the central study variables.

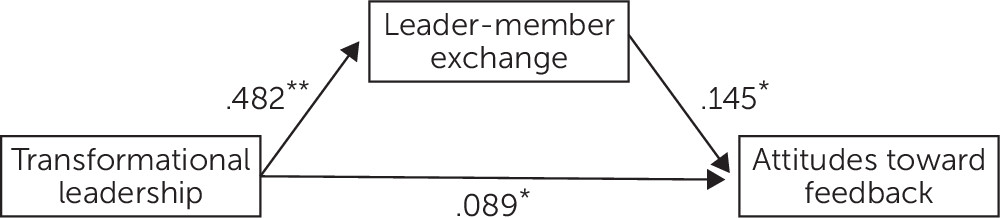

Figure 1 shows the standardized direct associations for the multilevel path analysis, and

Table 2 shows estimates for the direct and indirect effects of LMX and transformational leadership on attitudes toward feedback. Overall, model fit statistics indicated good model fit (χ

2=8.09, df=7, p=0.32; CFI=0.99; TLI=0.98; and RMSEA=0.02). Results showed that transformational leadership (β=0.09, SE=0.03, p<0.01) and LMX (β=0.15, SE=0.04, p<0.01) were directly and significantly associated with practitioner attitudes toward feedback. Both higher levels of transformational leadership and supervisor-practitioner relationships of higher quality were related to more positive practitioner attitudes toward feedback, supporting hypotheses 1 and 2. In addition, the results indicated an indirect relationship between transformational leadership and practitioner attitudes toward feedback through LMX (β=0.07, SE=0.02, p<0.01), a finding that was further supported by the significant Sobel test (p<0.01). Higher levels of transformational leadership were associated with more positive practitioner attitudes toward feedback through higher quality supervisor-practitioner relationships, supporting hypothesis 3. None of the control variables had statistically significant associations.

We conducted post hoc multilevel path analyses to determine whether any of the individual dimensions of the transformational leadership scale were driving the results. These models produced the same pattern of significant results as the model with the full transformational leadership scale (i.e., each transformational leadership dimension had a significant direct relationship with attitudes toward feedback, as well as a significant indirect relationship with attitudes toward feedback through LMX), suggesting that no single dimension was driving the findings.

Discussion

Leadership is increasingly becoming a focal point for research on effective implementation of EBPs (

12,

21,

35,

69,

70). Transformational leadership has been linked to EBP adoption, implementation climate, practitioner attitudes toward EBPs, fidelity, and sustainment (

10,

28,

50,

71,

72). This study extends research on transformational leadership by demonstrating its effects on practitioner attitudes toward feedback. LMX is less frequently studied in implementation research but played an important role in this study, suggesting that researchers should consider its contribution to the implementation process.

This study also contributes to work investigating how various forms of leadership operate independently and together to affect desired organizational goals (

41,

44,

45,

73). Our study explored the relationship between transformational leadership and LMX and showed how they may function simultaneously in an organization to influence how practitioners experience supervision and feedback. The finding that transformational leadership affects outcomes through LMX is in line with other results suggesting similar mechanisms of action (

34,

45).

Because ongoing supervisory monitoring and feedback are critical for implementation of EBPs and high-quality clinical practice, fostering an environment that encourages openness to feedback is essential (

3,

10). Our results suggest that supervisors with a strong transformational leadership style can inspire and motivate practitioners to be open to feedback and that a high-quality supervisor-practitioner relationship provides a channel through which transformational leadership has its influence. Supervisors can build trust with practitioners by alleviating their concerns about seeking and receiving feedback and reassuring them that the benefits of feedback (e.g., developing new skills and improving care) outweigh the costs (e.g., admitting mistakes) (

74).

This study focused on practitioners’ perceptions, but other research has suggested that leader-practitioner agreement on ratings of leadership behaviors is important to consider as well. For example, greater discrepancies between leader and practitioner perceptions of leadership behavior are associated with more negative organizational cultures (

75). Moreover, when leaders rate their own implementation leadership lower than do practitioners (i.e., “humble leadership”), organizational climate supporting EBP implementation is better (

76). These results illustrate the complexity of leader-practitioner dynamics and the need to develop and test nuanced approaches to leadership for promoting EBP implementation (

21).

Given evidence of the critical role leadership plays in developing a workforce that can respond to demands for implementation, administrators and policymakers should invest in evidence-based leadership training interventions. Research suggests that supervisors can be taught transformational leadership skills and coached to develop stronger bonds with their employees (

53,

77,

78). Similar to the process of training practitioners during EBP implementation, effective leadership training requires personalized training and coaching for leaders across multiple organizational levels (

21). The Leadership and Organizational Change for Implementation (LOCI) strategy is being tested in multiple service settings to evaluate its impact on outcomes such as organizational climate for EBPs, attitudes toward EBPs, and EBP fidelity (

21). As in LOCI, leadership interventions should be multifaceted and support leaders in strategies to articulate vision, motivate practitioners, and develop stronger relationships with practitioners as well as lead implementation of EBPs (

79). Experiential team-building workshops may also facilitate the development of higher quality supervisor-practitioner relationships (

80).

Some limitations should be considered when interpreting our results. First, we assessed practitioners’ attitudes toward feedback rather than their actual feedback-seeking behavior or their incorporation of feedback into practice. Although it is reasonable to expect that attitudes about feedback influence whether one seeks or uses feedback, care should be taken when drawing conclusions about the findings. Second, the cross-sectional design inhibits our ability to draw causal inferences. It is possible that practitioners who are more open to feedback tend to view their supervisors more favorably, and more research is needed to investigate the directionality of relationships between variables. Third, although the relationships between leadership and practitioners’ attitudes toward feedback were robust, the modest parameter estimates suggest a need to explore additional predictors of practitioner attitudes toward feedback in future studies. These predictors may include practitioner-level variables (e.g., emotional intelligence or goal orientation), team- or organizational-level variables (e.g., organizational culture and climate), and the fit between the practitioner and job demands and abilities (

19,

20). Fourth, data were collected exclusively from staff members, potentially introducing common method bias (

81). Finally, the generalizability of the study’s findings to other mental health treatment settings may be limited given that many participants were in the early career role of working toward licensure (i.e., student interns or registered interns). The results may also have limited generalizability to organizations and practitioners with different client populations, geographic locations, and leadership structures. In addition, the age of the study data warrants caution when generalizing to current settings. Future research with prospective designs, more objective measures, and different sample compositions can address some of these limitations.

Conclusions

This study contributes to evidence indicating that leadership plays a key role in shaping the organizational context of mental health service organizations. Future research should focus on developing and testing effective methods for translating research findings regarding leadership into usable interventions and strategies for mental health treatment organizations (

21). To improve practitioner attitudes toward feedback that supports the implementation of EBPs, leadership interventions should train supervisors in both transformational leadership and the cultivation of high-quality relationships with staff.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the community-based organizations and clinicians for their participation in this study.