Benzodiazepines are prescribed to over 5% of the U.S. adult population, and use is growing (

1–

3), concentrated among middle-aged adults, for whom use increased nearly 50% from 1996 to 2013 (

1). However, the prevalence of benzodiazepine use among adults ages 65 and older has been shown to be highest, at 8.6% (

1). Prescribing to older adults has been considered potentially inappropriate for decades, given associated harms, including falls and fractures (

4–

7); however, the growth in benzodiazepine prescribing has been accompanied by increases in related adverse events for adults of all ages. One area of concern has been their combined use with opioids, given the increased risk of overdose and overdose death among opioid users coprescribed benzodiazepines (

8–

10). But benzodiazepines pose risks of their own. In an analysis of emergency department visits from 1999 to 2006 for poisoning from opioids, sedatives (sleep promoting), or tranquilizers (anxiolytics or muscle relaxants), the largest absolute growth was in benzodiazepine-related poisonings (

11), and benzodiazepine-related overdose mortality grew nearly fivefold from 1996 to 2013 (

1). Concerns related to benzodiazepine prescribing have spread beyond older adults and beyond coprescription with opioids (

12).

The growth in adverse outcomes suggests that benzodiazepine prescribing and misuse in the United States have increased in tandem; however, less is known about benzodiazepine misuse. After marijuana use, prescription drug misuse—defined here as use in a manner other than prescribed or by a person to whom it was not prescribed—is the most common type of illicit drug use (

13). Most recent benzodiazepine-related work has focused either on misuse in the context of opioid use (

14–

16) or on tranquilizer or sedative medication misuse—but not on benzodiazepines specifically (

17,

18). The lack of information about misuse among older adults is particularly striking because they are prescribed benzodiazepines at the highest rates, are most at risk of related adverse events, and have higher rates of use of alcohol and other substances than prior aging cohorts (

19,

20). A recent systematic review of benzodiazepine and opioid misuse among older adults (

21) found just one study that estimated potential benzodiazepine misuse among older adults in the United States (

22). Given their widespread use, abuse potential (

23), and related risks, surprisingly little is known about benzodiazepine misuse.

Addressing the growing problem of benzodiazepine use and misuse first requires information about the current scope and nature of misuse. As a result of a 2015 redesign, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) now provides detailed information regarding prescription drug use and misuse in the United States, including the type of and reasons for misuse and the source of the misused medication. We used data from the redesigned NSDUH to develop national estimates of benzodiazepine use and misuse among U.S. adults and to determine whether characteristics associated with misuse varied by age, given the unique risks of these medications to older adults and the need for targeted interventions to reduce misuse.

Methods

This analysis used data from the NSDUH, which measures the prevalence and correlates of drug use among the U.S. civilian, noninstitutionalized population (

24). The survey uses a 50-state design with an independent, multistage area probability sample; is administered by RTI International; and is sponsored by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Respondents complete two computer-assisted segments, one conducted by an interviewer and a second audio-assisted portion without interviewer help, intended to provide a private environment to increase the likelihood of honest reporting of illicit drug use.

NSDUH was redesigned in 2015 to collect more detailed information on the use and misuse of prescription medications, including benzodiazepines—in prior years, questions were limited to misuse exclusively (

25). The pre-2015 NSDUH definition of misuse was limited to “nonmedical use,” but the 2015 definition was revised to include “in any way a doctor did not direct.” This analysis was limited to data from respondents ≥18 in the 2015 and 2016 survey years (N=86,186), the years available since the redesign.

Benzodiazepine Use or Misuse

Respondents could report benzodiazepine use through survey queries about tranquilizer or sedative use. NSDUH classifies tranquilizers as medications specifically for relief of anxiety or muscle spasms and sedatives as medications for insomnia. This analysis was limited to the 10,290 respondents who specifically reported benzodiazepine use in response to the tranquilizer and sedative items. [Additional details are provided in an online supplement to this article.]

For each medication class, NSDUH collected information on past-year use (that is, taken as prescribed) and misuse. Respondents were asked about the specific manner of misuse: without a prescription, in greater amounts or more often than prescribed, longer than prescribed, or any other use other than as prescribed. Next, they were asked about reasons for misuse: “to relax,” “to experiment,” “to get high,” “for sleep,” “for emotions,” “to counter the effect of another drug,” because they were “hooked,” or another reason. Finally, respondents were asked about the source of medication for misuse (for example, their clinician or a friend or relative). For this analysis, the misuse category identifies a respondent who reported any past-year misuse, even though that respondent may have also used the benzodiazepine as prescribed. Presence of abuse or dependence was determined by DSM-IV criteria.

Other Respondent Characteristics

We included respondent self-rating of health and past-year presence of a major depressive episode, suicidal thinking, and mental illness by using a variable developed by NSDUH based on responses to items about psychological distress, functional impairment, symptoms of a major depressive episode, and suicidal ideation (

26).

We included past-year alcohol, marijuana, and heroin use or abuse or dependence; past-year use of tobacco products; and past-year use, misuse, or abuse of or dependence on prescription opioids and stimulants.

Finally, respondents provided sociodemographic information, including age, gender, race-ethnicity, and household income.

Analysis

Analyses incorporated weights, clustering, and stratification, using NSDUH design elements to account for the complex survey design and generate nationally representative estimates. After determining population characteristics among adult respondents, we estimated the prevalence of benzodiazepine use—as prescribed, misuse, and any use—among adults overall and by age group. We compared demographic and clinical characteristics of adults with and without any benzodiazepine use by using chi-square tests. We determined the magnitude of the association between respondent characteristics and benzodiazepine use by using multivariable logistic regression (0, no benzodiazepine use; 1, any benzodiazepine use), adjusting for other sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

We then limited the analysis to respondents who reported any past-year benzodiazepine use, split into those who reported use as prescribed or misuse. We compared characteristics of each group by using chi-square tests. Next, we completed bivariate logistic regression for each characteristic (0, use as prescribed; 1, misuse), including an interaction by age (younger [18–49] versus older [≥50]), to determine whether age moderated the association of each characteristic with misuse. We used ≥50 years as the age cutoff because prescription benzodiazepine use among those in later middle age approaches that of adults ages ≥65 (

1), and the youngest respondents in the Baby Boom cohort (those born in 1964) would have turned 50 just before the 2015 NSDUH. We used multivariable logistic regression to determine the characteristics associated with misuse among benzodiazepine users, adjusting for other demographic and clinical characteristics.

The final stage of analysis examined the characteristics of past-year benzodiazepine misuse overall and by age. We determined the type of, reason for, and source of misused benzodiazepine, along with the specific benzodiazepine misused.

Analyses were conducted with Stata, version 13.1, with two-sided tests and α=.05. The University of Michigan Medical School Institutional Review Board (IRB) considers analyses of deidentified, publicly available data exempt from IRB approval.

Results

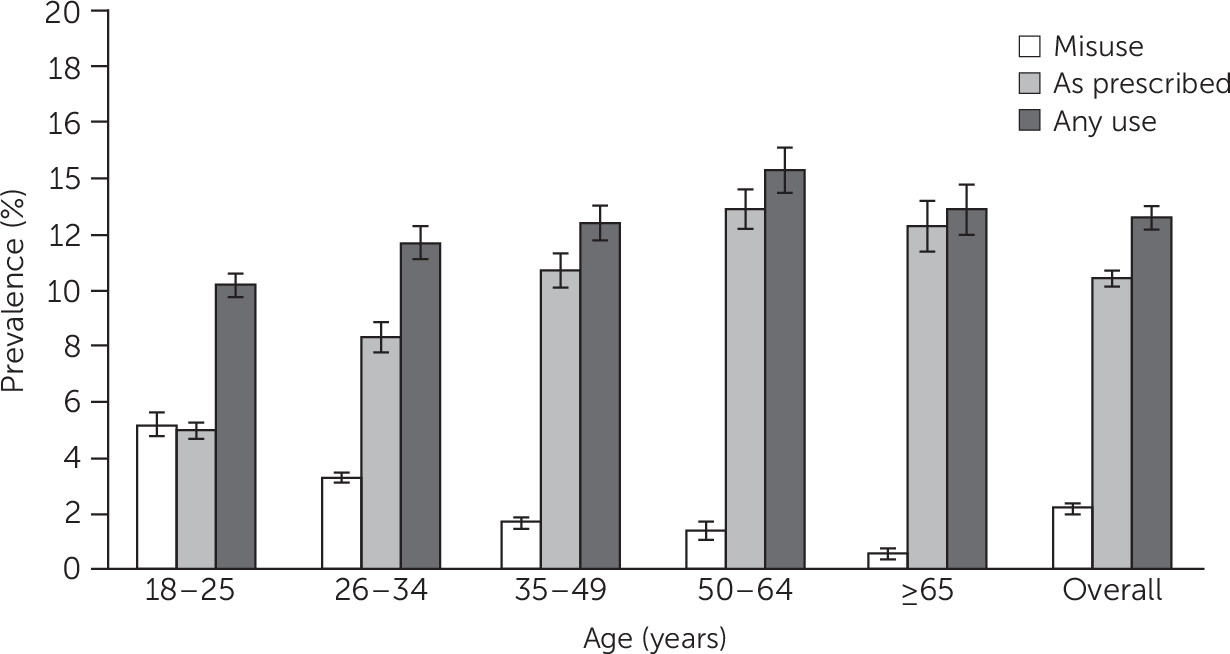

Prevalence and Predictors of Any Benzodiazepine Use

An estimated 30.6 million adults per year in the United States (95% confidence interval [CI]=29.7–31.5 million) used benzodiazepines in the past year, an overall prevalence of 12.6% (CI=12.2%−12.9%), including misuse among 2.2% (CI=2.0%−2.3%) and use as prescribed among 10.4% (CI=10.1%−10.7%). Use among adults ages 50–64 was highest (

Figure 1 and

Table 1).

Women and non-Hispanic white respondents reported the highest rates of any past-year use. In the adjusted logistic regression model (

Table 1), female gender, older age, and more education were all associated with increased odds of use, and respondents’ race-ethnicity other than non-Hispanic white was associated with lower odds of any benzodiazepine use.

The presence of past-year mental illness was associated with increased odds of any use, as was worse self-rated health. In almost every instance, past-year use, misuse, or abuse of or dependence on tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, heroin, prescription opioids, or prescription stimulants was associated with any benzodiazepine use. Among all substances, prescription opioids were most strongly associated with benzodiazepine use at every level, from use as prescribed through abuse or dependence.

Prevalence and Predictors of Benzodiazepine Misuse

Among respondents who reported any benzodiazepine use, 25.3 million (CI=24.5–26.1 million) reported use as prescribed by their clinician, and 5.3 million (CI=5.0–5.6 million) reported misuse. Use as prescribed was highest among adults ages 50–64 (

Figure 1 and

Table 2). Misuse was highest among the youngest adults and decreased with age. Most benzodiazepine use among respondents ages 18–25 was misuse (5.2%, CI=4.8%−5.6%). In contrast, misuse was reported by just .6% (CI=.4%–.8%) of adults ages ≥65.

Bivariate logistic regressions testing for a moderating effect of age on the associations between respondent characteristics and misuse found a statistically significant interaction in just three instances (

Table 2). Even though age itself was strongly associated with lower odds of misuse, because of the minimal evidence for a moderating effect, characteristic × age interactions were not included in the multivariable model. Females had lower odds than males of misuse; however, apart from age, no other demographic characteristic was associated with misuse. Fair or poor health self-rating was associated with lower odds of misuse, whereas any level of marijuana or alcohol use was associated with increased odds of benzodiazepine misuse. Prescription opioid use as prescribed was associated with lower odds of benzodiazepine misuse, whereas opioid misuse and abuse or dependence were the characteristics most strongly associated with benzodiazepine misuse.

Characteristics of Misuse Among Younger and Older Adults

The most common type of benzodiazepine misuse overall was use without a prescription, although this type of misuse use was less likely to be reported by respondents ages ≥50, compared with younger adults (ages 18–49) (

Table 3). Compared with younger adults, older respondents were more likely to report using their benzodiazepine more often than prescribed.

The most common reason for misuse overall was to relax or relieve tension, followed by to help with sleep. Older adults were significantly more likely than younger adults to endorse misuse to help with sleep, and they were much less likely to report misuse to get high.

The most common source of the misused medication for both younger and older groups was from a friend or relative. When all sources of benzodiazepines were combined—free, bought, or stolen—a friend or relative was the source for nearly 70% of respondents reporting misuse. The next most common source was a single clinician.

Alprazolam was the most common benzodiazepine misused. Compared with younger adults, older adults were more likely to misuse lorazepam or diazepam. Respondents who reported misuse did so on 5.4 days (SE=.3) in the past month. Among those with benzodiazepine misuse, 4.6% (CI=3.7%−5.6%) and 6.8% (CI=5.6%−8.2%) met criteria for past-year abuse and past-year dependence, respectively.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional analysis of survey data from U.S. adults, the annual prevalence of benzodiazepine use, when both prescription use and misuse were included, was 12.6% and exceeded 15% among women and non-Hispanic white respondents. By age, the highest rate of overall benzodiazepine use was among adults ages 50–64. More than 2% of respondents overall endorsed misuse, which was highest among the youngest adults (ages 18–25), for whom misuse exceeded as-prescribed use. In contrast, adults ages ≥65 had the lowest prevalence of misuse (.6%).

To our knowledge, this is the first analysis of benzodiazepine use in the United States to find that the highest prevalence of use is no longer among adults ages ≥65. Although use among those ages ≥65 has not been declining (

1,

3), the decades of evidence regarding safety concerns (

4,

7,

27) and professional guidelines (

6,

28) recommending limited use among older adults may have helped slow growth. In contrast, the aging Baby Boomers—who constituted nearly the entire 50–64 age group in this analysis—have higher rates of alcohol and other substance use, compared with previous cohorts of aging adults (

19,

20,

29). The high level of use among these late-middle-age adults means that potentially inappropriate prescribing of benzodiazepines to older adults may continue as this cohort ages.

The NSDUH redesign affords new insights into the nature of benzodiazepine misuse, which accounted for nearly 20% of all use among adults but which was much more common among younger adults. Although age largely did not moderate the patient characteristics associated with misuse, the nature of misuse varied between younger (ages 18–49) and older (ages ≥50) adults. Misuse without a prescription was the most common type of misuse, although this was more common among younger adults; older adults were more likely to use their benzodiazepine more often than prescribed. Misuse to help relax and to help sleep were the main reasons for misuse among both age groups, although sleep was a relatively larger driver of misuse among older adults. Relatively little misuse was for experimentation or to get high, and few respondents who reported benzodiazepine misuse met criteria for past-year abuse or dependence.

Taken together, these misuse findings raise questions about the underlying contributors to misuse as defined and identified in the NSDUH. Younger adults are more likely than other age groups to lack health insurance (

30), whereas the most common reasons for misuse (for example, to relax or relieve tension) were reasons for which a clinician might prescribe a benzodiazepine or refer for behavioral treatment. Therefore, a significant proportion of NSDUH-defined “misuse” could reflect use for untreated symptoms among those with poor access to care—specifically, for behavioral treatments for insomnia (

31,

32) or anxiety disorders (

33,

34). The development of interventions, such as Web-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia, may help increase access to benzodiazepine alternatives for those who lack access to providers or insurance or both (

35).

Clinicians should recognize their role as a source of misused benzodiazepines, either through medication that they prescribe but that is used other than as instructed or as the source of prescribed medication given for misuse to a friend or relative. In addition to being mindful of their role as a potential source of misused medications, clinicians have an important role in understanding the reason for their patients’ misuse to determine the appropriate intervention. If patients are consuming prescribed medication faster than expected, clinicians should determine the reason. Is it for inadequate symptom control? For additional indications—for example, prescribed for anxiety but also used for sleep? Is a patient allowing another family member to use some? Some misuse may be for symptoms appropriately treated by a benzodiazepine, but clinicians should be mindful of other potential reasons for misuse. An uninsured young person may use an older relative’s prescribed benzodiazepine for insomnia rather than to get high, but this certainly was not the intention of the prescribing clinician.

Other substance use disorders were strongly associated with benzodiazepine use and misuse. Benzodiazepine misuse was most strongly associated with misuse of and abuse of or dependence on prescription opioids and stimulants. Prescription drug monitoring programs are an important tool for clinicians to understand which of their patients may be misusing other medications and would thus be at high risk of benzodiazepine misuse. The association of alcohol abuse or dependence with increased odds of benzodiazepine misuse is particularly concerning in light of the increased potential for fatal poisoning when these substances are combined (

36,

37). This has received much less attention than the opioid-benzodiazepine combination, even though alcohol use disorders are more prevalent than prescription opioid use disorders.

Our findings that women, older respondents, and non-Hispanic white respondents reported higher rates of benzodiazepine use are consistent with previous work (

1,

2,

38–

40). In contrast, women and older respondents were less likely than men and younger respondents to report misuse. This may further support the hypothesis that higher misuse is partly a function of limited access to a prescribed option—limited for younger individuals because of lack of insurance and for men because of minimal disclosure of mental health concerns to providers (

41). However, higher misuse was not found among racial and ethnic minority groups, even though they have limited access to specialty mental health care and lower rates of insurance, compared with non-Hispanic whites (

30).

Our estimate of the annual prevalence of any benzodiazepine use—12.6% overall and 10.4% as prescribed—is higher than other recent results. A study using data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) found that 5.6% of adults filled a benzodiazepine prescription in 2013 (

1), and an analysis of data from the 2013–2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) found benzodiazepine use among 4.2% of adults (

42). Survey differences may partly account for the different estimates: NHANES assesses medication use in the past 30 days (

43), whereas MEPS samples households, with information often provided by a single knowledgeable informant (

44). MEPS respondents may underestimate the number of unique medications used in a year, specifically underreporting those used for a shorter duration or with fewer fills (

45), which is how benzodiazepines may be prescribed. Finally, NSDUH is the only survey to include misuse. Our estimate of misuse is similar to an NSDUH estimate from 2002–2004 (

17), although that analysis examined tranquilizers and sedatives overall and was not limited to benzodiazepines.

Our analysis had a number of limitations. NSDUH is cross-sectional, and because of the 2015 redesign, we could not track trends in misuse over time. There was a potential for nonresponse bias. NSDUH response rates have been declining, although this is unfortunately true for several federally administered national surveys (

46). NSDUH is nationally representative but of the civilian population and thus does not include active-duty members of the military or institutionalized adults.