Researchers have paid much attention to frequent users of emergency services in order to cut down on what has been considered nonemergent use (

1). One particular group has surfaced as warranting particular attention: people with psychiatric diagnoses (

2). The results of the existing literature highlight that the service needs of this group are not being met in many jurisdictions (

3–

5). The reasons for the frequent visits, as reported by users of mental health services, center on lack of alternatives (

5,

6), ease of access (

4,

5), needing shelter or medication (

4), feeling out of control, and family turmoil (

7). Curiously, and contrary to results of quantitative studies (

8,

9), some have found that the presence of symptoms did not lead to frequent use (

4). This discrepancy is a good illustration of why qualitative inquiry is necessary (

10). Epidemiological studies exploring the reasons for frequent use of emergency services in general hospitals are limited by the data available in the administrative records. Because the complexities of living with a mental illness are usually unmeasured, such studies have been satisfied with attributing frequent use to the presence of a mental illness diagnosis in the records instead of to the mechanisms underlying the link (

2). Qualitative work provides a greater understanding of the phenomenon, but more could be done to focus specifically on the reasons for frequent use among service seekers. Existing qualitative work tends to focus on general experiences, treating the reasons for frequent use as a theme among many (

3,

6). As a result, current research has agglomerated the lived experience of attending services with other elements, including the interactions service seekers have with staff and the visits’ precipitating factors (

5,

6).

Results

The distribution of diagnoses resembled previously reported patterns among frequent users (

17), with the exception of a marked overrepresentation of personality disorder: 11% (N=5) of our sample versus 2% (N=281) of previous population-wide estimates (

17).

Table 1 provides the demographic characteristics of our participants. Notably, our sample recorded a median of 8.9 visits each year participants were in contact with emergency services, with a range of 2.6 to 54.7 visits per year.

Because we intended to examine the reasons for frequent use of emergency services, we bypassed reasons that may have been the cause of isolated use (e.g., “I came once because I needed a medical certificate”) among frequent users.

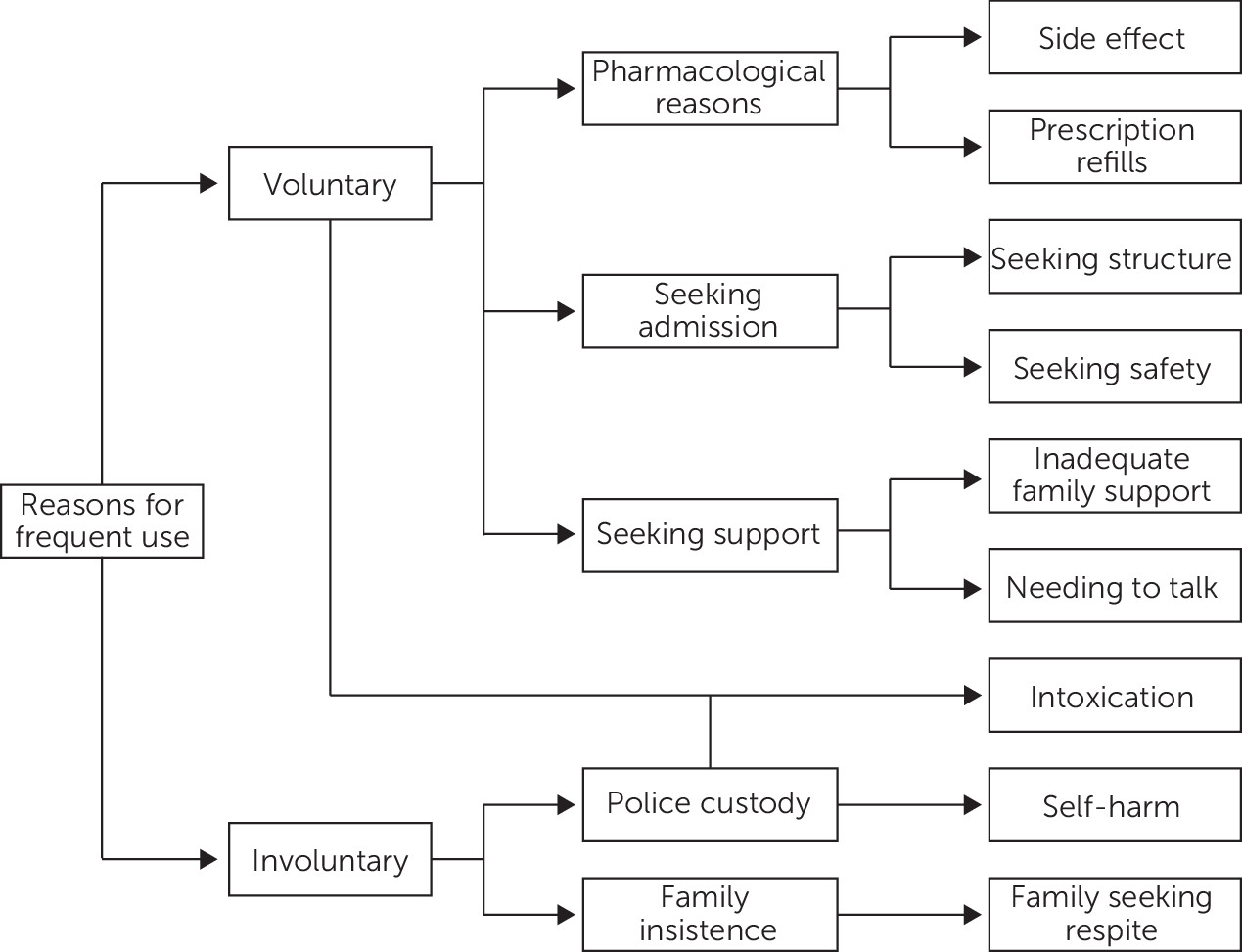

Figure 1 illustrates the structure of the data. (The

online supplement reports quotations supporting the themes and subthemes.)

Reasons for Voluntary Visits

Pharmacological reasons.

Several visits were due to the need for psychiatric services after office hours to adjust doses, refill prescriptions, or receive depot injections. In these cases, a need for medications or some aspect of care related to medication precipitated the visit. These were common reasons for frequent visits among employed individuals, whose employment and schedules put a lot of pressure on them:

So normally what I do is I tell the doctor that I cannot come [to my outpatient appointment], but I will come and go to the A&E [accident and emergency department] for my injection and for my medication, and then I go home and sleep after that. Worse come to worse I need to spend money on the taxi fare, but at least there is no pressure of waiting in the queue or, you know, having to answer calls or having to balance my thoughts between work and medication. (10011)

Being unable to conform to clinic schedules was frustrating for our participants, and they had limited choices other than to visit emergency services.

Seeking or avoiding admission.

Twenty-eight service users visited repeatedly, seeking admission for their safety or for the comfort they derived from being in a structured environment. Those who worried about their self-control (N=14, 32%) sought admission to isolate them from potentially dangerous situations, thereby obtaining safety. They sought admission because they had recognized signs that heralded a relapse, but at the time of their visit they had not yet experienced symptoms that would warrant admission:

I have tried before, but sometimes. . .some doctors they will tell you, “No, this is not the place.” You must have a very good reason, like you want to suicide, then they will admit you. You must tell them your life is in danger, you want to hurt yourself, then they can admit you. If you want to tell them, “Oh, I don’t want to make mistake outside, that is why I want to come here to admit myself,” they will not agree for you to stay. (10041)

Magnifying subacute symptoms could be highly problematic; in this study, three participants (7%) reported genuinely experiencing suicidal intentions at one visit but overstating the severity of their symptoms at other visits in order to obtain admission for their safety.

Seeking structure, comfort, and respite from the stressors of life led 14 of our participants (32%) to seek services on multiple occasions. Older participants, who had longer histories of institutionalization, spoke more of the comfort they derived from being in a familiar place.

The belief that the wards provided structure and comfort was not universally held. Six participants (14%) wished to avoid returning to the inpatient wards precisely because of the distressing events in chaotic wards. These participants adjusted their behaviors because of their frequent use. A consequence of prior admission was the adoption of strategies to avoid being readmitted. They avoided telling their physicians about their genuine complaints, which were usually related to self-harm, and instead mentioned complaints that did not warrant hospitalization:

They [emergency staff] are the last [people] I would go to because if they know that I have suicidal thoughts, I am afraid they would ward me at IMH [the Institute of Mental Health]. Every time I see the doctor here at IMH, I just tell her, “Oh, OK I am fine, everything is OK,” but that is not the truth, you see. It is, like, I just tell her, “Oh, I can’t sleep,” then you know, like, then she will give me medicine. (10023)

Participants who used this strategy wanted to retain control over which symptoms of their illness were treated, but they needed services nonetheless.

Seeking external support.

Participants found that emergency services gave them access to someone who took the time to listen genuinely when they needed to talk. Outpatient services did not offer time with clinical staff, or the interactions felt insincere, and participants’ experiences with medical professionals changed when the participants transitioned to outpatient services. They felt that outpatient services were unable to meet their needs and preferred to return to emergency services:

To me it [outpatient services] doesn’t help me, I just go in, I tell him that, and he prescribes me a new set of medicine, and that’s it? One session, 2 minutes, 3 minutes? To me, it is just nonsense. . . .Almost all my experiences there [emergency department], the doctor will scribble, scribble what I say down, at emergency. And then after that they will read awhile and then tell me how to help me, and whatnot. (10033)

This perception was especially relevant when people felt that family support was lacking. These participants could not depend on their family or outpatient services to unburden themselves of their daily stressors and sought, instead, the emergency services. The process of determining whether an individual required admission—the emergency psychiatrists’ primary task—allowed participants to talk freely and at their own pace.

Substance Use

Emergency services, easily accessible sources of care, were the default places where police brought participants with drug and alcohol use histories who were found intoxicated in public. Substance use, therefore, contributes to both voluntary and involuntary causes of frequent use of emergency services. Alcohol intoxication perpetuated service needs because it led to contact with police, a desire to seek help, or suicidal thoughts:

Yeah, got suicidal, and then got hearing voices. Too much alcohol, that time, I suffering outside. I got no proper place to sleep. (10016)

However, because treatment did not eliminate addictions or address housing instability (the latter was reported by five participants [11%]), participants found themselves frequently in need of rehospitalization, which often happened after paydays or quarrels with family, rooting the cause for frequent use of emergency services in social circumstance.

Reasons for Involuntary Use

Police custody led six participants (14%) to be remanded repeatedly to psychiatric emergency services for assessment because they had been arrested for putting themselves in dangerous situations (e.g., trying to jump from high-rises) or because of public nuisance behaviors linked to acute mental illness. Prior to the decriminalization of suicide in Singapore (which took effect in January 2020), police could charged those suspected of having deliberately harmed themselves with the intention of ending their lives. Three participants (7%) spoke openly about the police investigation, and one spoke extensively of the conditions of her probation following formal charges. Because of repeated contact with law enforcement, these participants learned that, although the charges were serious, the police officers involved in the investigation were empathic and wished to spare the individual from the criminal process.

At the insistence of family, some participants were frequently asked to go to (N=3, 7%) or were led to (N=7, 16%) to emergency services. In these instances, the family sought respite from dealing with challenging behaviors by admitting their kin. According to our participants, these visits were not the result of medical need:

I disturbed [my father] because he was sleeping and I asked him for money—$10 to buy cigarettes—then I disturb my father. That is why he got very angry and. . .he sent me to the A&E, and he wants the doctor to admit me. Actually at first the doctors don’t want to admit me, he say I am OK. “You got no problems, I don’t see that you are sick.” But my father say, “I cannot endure, because he was all the time disturbing me,” and I was sent to the ward. (10014)

Participants who spoke about these issues tended to be more reliant on their family for daily support. In these cases, participants usually attributed their deterioration to quarrels with family members.

Discussion

This is one of the few qualitative studies to look in depth at people’s self-reported reasons for frequently visiting a psychiatric emergency department. Describing reasons for frequent use revealed the need to also describe the consequences of help-seeking behaviors. Our results echo existing findings about the multiplicity of reasons that precipitate service seeking and the importance of control, safety, and family involvement (

5,

7). The lack of reliable alternatives for safety found in this study is also similar to qualitative studies done in markedly different cultural settings (

5,

6).

Service providers suggested that intoxication, medication-seeking behaviors, families seeking admission, and remand cases were the most common contributors to frequent use (

17), which is in line with predictors of frequent use (

27). Our interviews echo some of their beliefs. Additionally, our findings highlight that some frequent service users seek admission for safety (

5,

6,

28) or visit to talk with empathetic professionals. The idea that emergency services represent a low-barrier source of care also echoes findings from other contexts (

5,

29).

A curious finding is the way in which frequent service users modified symptoms to obtain a desired outcome. Our results present a different perspective on malingering, noted to be particularly prevalent in this group (

30). For those who worried about a potential relapse, magnifying the severity of the symptoms assured their admission. Denying the option of admission has a well-documented negative impact on service user satisfaction (

31) and, as we have shown, leads to strategic changes in service-seeking behaviors. For those dissimulating severe symptoms to avoid admission, sleep disturbances appear to be a placeholder illness. Participants knew that their actual thoughts of self-harm and suicide would warrant admission but that reporting sleep disturbances would not. This phenomenon has genuine implications for managing suicide (

32). Although thoughts of self-harm, rooted in difficult social circumstances, may prompt the visit, people censor their complaint to obtain their desired outcome. These people may receive inadequate and improper treatments because service providers cannot obtain sufficient information to establish a suitable treatment.

Implications

The impact of family members seeking admission for their kin could be limited by addressing the unmet need for respite (

33). Adopt respite policies similar to those used in the care of people with dementia may be beneficial (

34). However, the literature has yet to offer clear guidance on how such services should be integrated into the system (

35). For respite services to be most effective, admission processes should bypass emergency services and should be planned before the need for respite becomes critical. More could be done with tools such as advanced psychiatric directives (

36), especially in Asia (

37), to enable service users to cocreate the strategies designed to achieve the resolution of their crisis (

5).

Patient-controlled hospital admission is a novel approach to reduce coercive measures (

33). If traditional pathways force service users to adapt their symptoms to meet the criteria for admission, self-controlled admission may improve open communication by eliminating the need to magnify symptoms.

Limitations

We limited our sample to people who visited our emergency department frequently. We therefore omitted input from people who may have experienced psychiatric issues but found solutions prior to their use becoming frequent.

It is possible to dispute the point at which we found the participants’ reasons for frequent use in the causal chain of events. If we had pressed participants to explain further why they had difficult behaviors that led their family to seek respite, for example, we may have uncovered additional reasons. We did not press participants to provide additional explanations in order to avoid an interrogative line of questioning.

Finally, cultural differences may explain our results. For example, the criminal charges that follow attempted suicides changed the way our participants sought services. However, self-harming behaviors have had a similar effect on censoring presentation of symptoms elsewhere (

32).