Opioid analgesic misuse is a significant public health concern facing the United States (

1,

2). In 2015, approximately 4 million people ages 12 years and older misused opioid analgesics (

3). Opioid analgesic misuse is associated not only with substantial economic burden (

4–

6) but also with high mortality rates and significant morbidity, which lead to hospitalizations and emergency department visits (

7–

9). Additionally, misuse can lead to addiction, necessitating inpatient or outpatient treatment for substance use disorder. Opioid analgesic misuse is also a gateway to heroin use, which greatly increases the risk of accidental lethal overdose (

10,

11). Deaths involving opioids increased more than threefold since 2000, reaching more than 15,000 in 2015 (

12,

13).

Much opioid misuse originates from prescriptions intended for therapeutic use (

14). The link between prescriptions intended for therapeutic use and misuse may be related to prescribing practices, patient drug-seeking behaviors, or both. Overprescribing of opioids, prescribing of long-acting opioids for acute pain, and/or overlapping prescriptions of multiple opioids or of opioids and benzodiazepines may unintentionally contribute to misuse (

15–

19). Examples of patient behaviors that can contribute to misuse include seeking opioids from multiple providers or pharmacies and using opioids for nonmedical reasons (

20,

21). Patients who are exposed to these factors—all of which are considered problematic prescription practices—are at greater risk of opioid misuse (

15,

22–

24).

Estimating the prevalence of potentially problematic opioid prescriptions is important because of its link to misuse, which can increase morbidity and mortality. Although a wide variety of policies address opioid misuse, there is room for additional strategies, especially in reducing potentially problematic prescriptions. Previous studies that examined rates of potentially problematic prescriptions were limited to small databases, a small number of potentially problematic prescription practices, or both (

25–

28).

Methods

Data

We used claims data from the 2005–2015 IBM MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database and the Multi-State Medicaid Database. These databases contain detailed patient-level claims provided directly by health plans and offer the largest convenience sample available in proprietary claims databases. The MarketScan databases are consistent with the definition of limited data sets under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act Privacy Rule and contain no direct patient identifiers.

Sample Population and Setting

Each year, we identified individuals aged 18–64 years with a pharmacy claim for opioid analgesics in the commercial and Medicaid data. We restricted the sample to individuals who had at least 90 days of continuous enrollment that year and had no hospice claims or cancer diagnoses in the 12 months prior to their first opioid fill of the year. We excluded opioid pharmacy claims that appeared to be invalid (e.g., days’ supply of ≤0 or >365 or pill quantity of ≤0) or were outliers (pill quantity in the 99th percentile or higher). We also excluded from the Medicaid analysis any individuals who were dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid because we did not have pharmacy claims paid by Medicare. In addition, for a more robust comparison of Medicaid and private insurance enrollees, we limited the sample to data contributors (employers, health plans, and states) that provided data for each of the years of the study. We excluded the private claims data from any state for which we did not have corresponding Medicaid data. After applying these criteria, we identified 45,921,008 private and 7,164,739 Medicaid enrollees with a valid opioid pharmacy claim over the entire study period.

Characteristics of Included Prescriptions

We included all forms of Schedule II–IV opioid pain medications (see Appendix Table A1 for a list of each included opioid and its associated morphine milligram equivalent conversion factor. Because methadone can also be used to treat opioid dependence, we used Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System service codes to identify and exclude claims for methadone for treatment of substance use disorders.

The MarketScan pharmacy claim does not include information on the prescriber or the reason (diagnosis) for the prescription. Therefore, to analytically determine the prescriber and the diagnosis, we looked back 7 days from the date of each opioid fill to identify the inpatient, outpatient, or emergency department claim that occurred closest to the fill date. We considered only outpatient visits in which an opioid could have been prescribed by using procedure and revenue codes, including 90791–2, 99201–5, 99211–5, 99217–20, 99241–5, 99341–5, 99347–50, 99384–7, 99394–7, G0463, H0034, H2000, H2010, T1015, 0510, 0515–7, 0519–23, 0526, 0528–9, 0911, and 0982–3. We assigned the provider ID on that claim to the opioid prescription. We used the diagnoses on this most recent claim to identify the reason for the opioid prescription. If there were no outpatient, inpatient, or emergency department claims in the 7 days prior to the fill date, we recorded the prescriber and reason as missing. If inpatient and outpatient date of service overlapped within the prior 7 days, we used the outpatient claim to identify the diagnosis. For refills, we assigned the prescriber and diagnosis from the initial fill.

Indicators of Potentially Problematic Prescription Behavior

We constructed five binary indicators of potentially problematic prescription practices on the basis of the previous literature (

24,

30). In addition, we created a dichotomous variable to indicate whether the individual had two or more incidents of any of these five practices in each year of the study period. We defined high-dose opioids as opioid prescriptions for greater than 120 morphine milligram equivalent for 90 or more consecutive days. We calculated the daily dose of each opioid prescription by dividing the number of pills by days’ supply, which allowed us to measure the prescribed number of pills each day. We multiplied that number by pill strength to calculate daily total dose. We converted this number to the morphine milligram equivalent dose by using existing conversion factors established by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (

31) (see Table A1, which is available as an

online supplement to this article). If there were overlapping opioid prescriptions, we added the daily dose in morphine milligram equivalents for each prescription.

To identify long-acting opioid prescriptions written for acute pain, we used the National Drug Code to distinguish long-acting opioids from immediate-release opioids. We categorized pain as acute or chronic by using the Chronic Condition Indicator, a diagnosis classification tool developed as part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (

32), applied to the first four diagnoses on the claim. Consistent with the literature (

25,

27), we identified opioid overlap as instances in which a patient filled or refilled an opioid drug prescription while he or she still had a supply of seven or more days (assuming the drug was taken as prescribed on the pharmacy claim). We applied the same rule to identify opioid-benzodiazepine overlap, a potentially lethal combination given that both drugs sedate users, suppress breathing, and impair cognitive functions. To identify multiple providers, we counted the number of unique prescriber IDs associated with opioid claims for each person in each year. We categorized individuals with three or more opioid prescribers as having multiple prescribers.

Analytical Approach

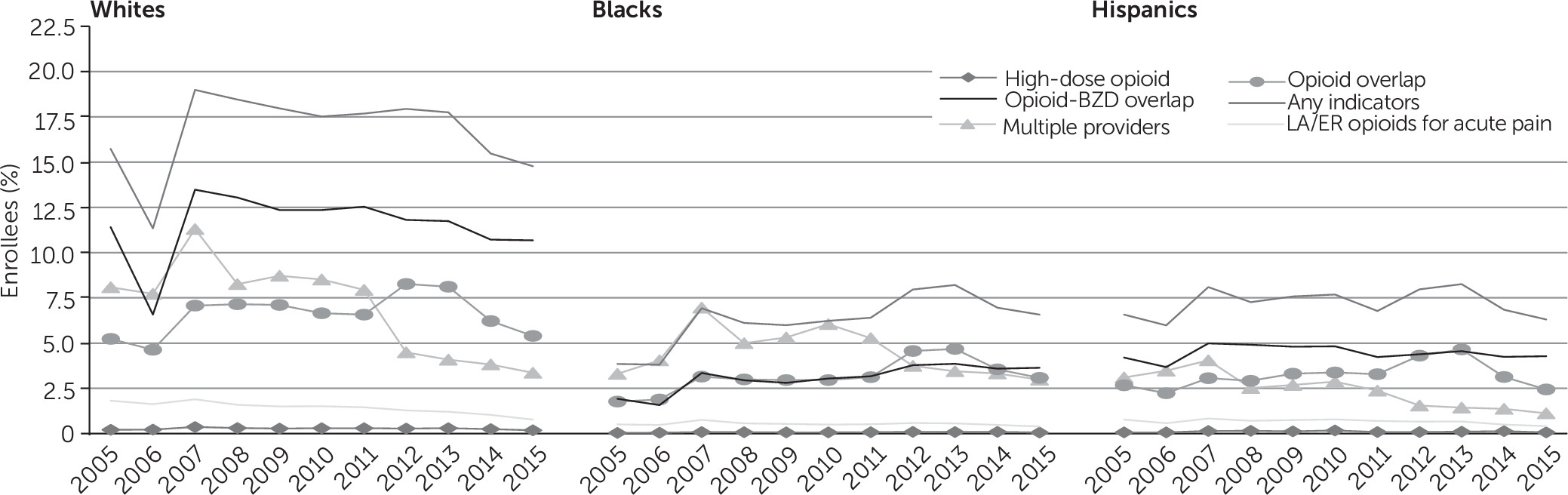

We calculated the number and percentage of enrollees with any potentially problematic prescription practice, as well as the number and percentage of enrollees with each specific practice type (see Tables A2 and A3 in the online supplement). In our presentation of results, we focus on the percentage of patients with two or more incidents of long-acting opioid prescriptions for acute pain, high-dose opioids, multiple providers, and overlapping prescriptions as a conservative approach to identifying potentially problematic prescription practices. Rates were stratified by sex, age group, and health plan type for both private and Medicaid enrollees, by race and ethnicity for Medicaid enrollees only (we did not have complete race and ethnicity data for private insurance). Finally, we used the chi-square test to examine the significance of change in yearly rates compared with baseline (2005).

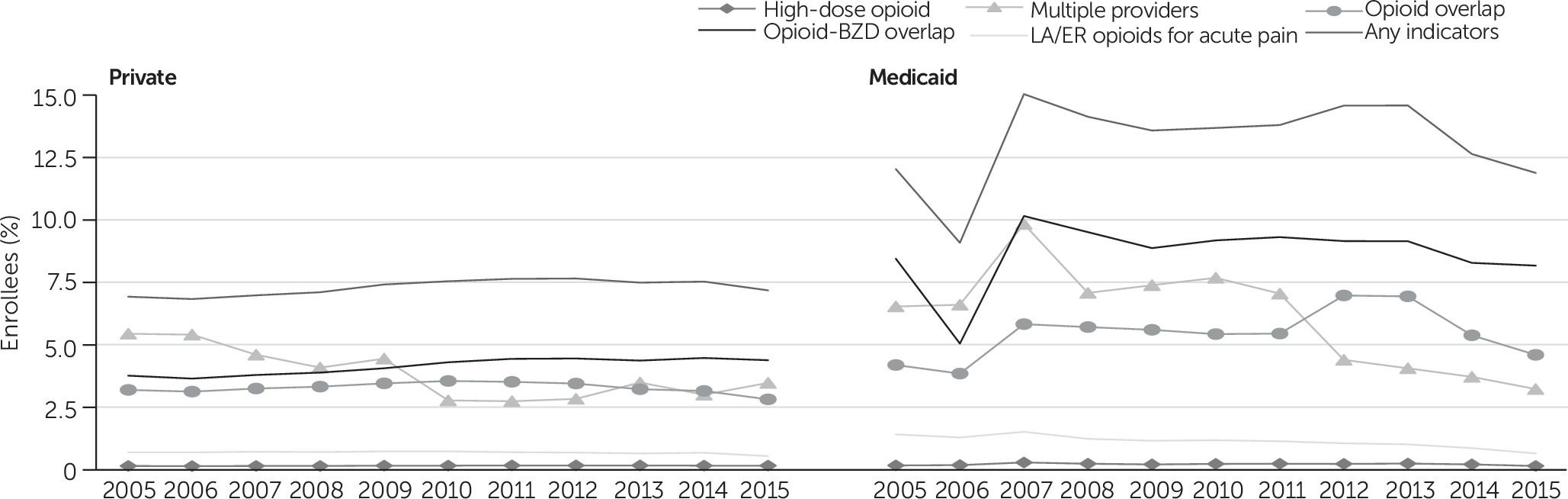

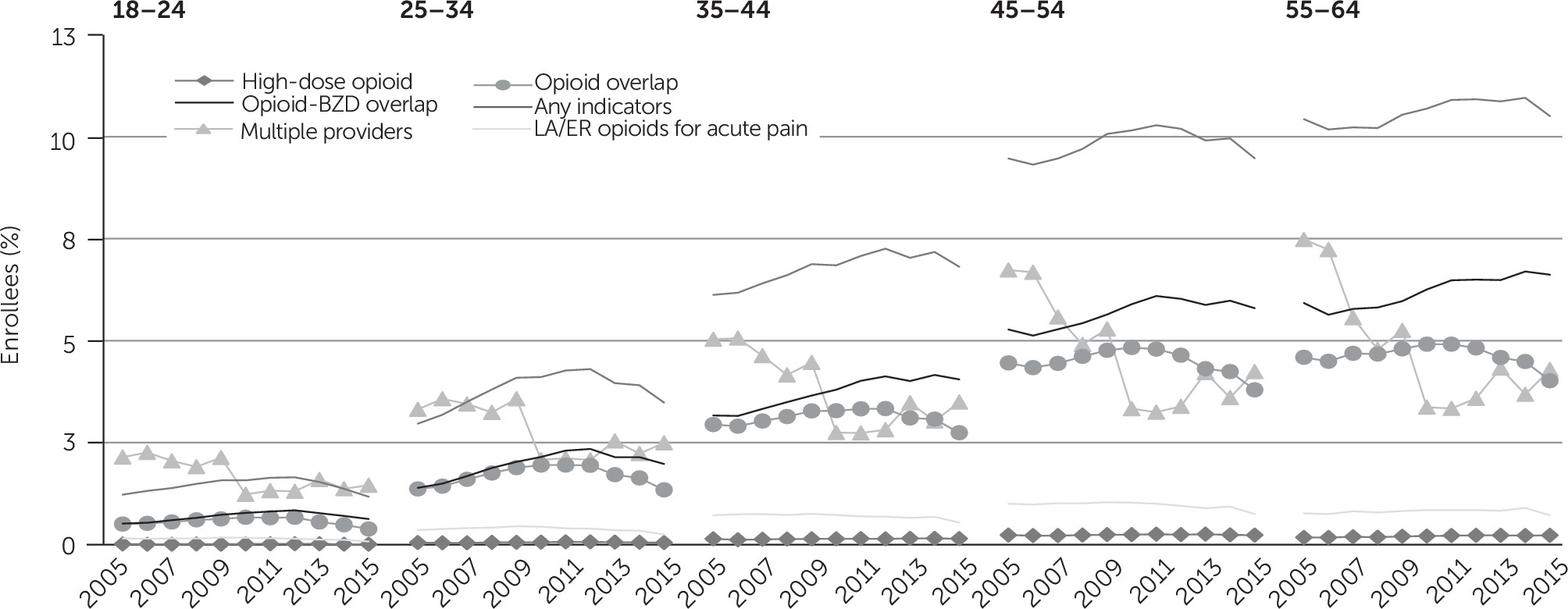

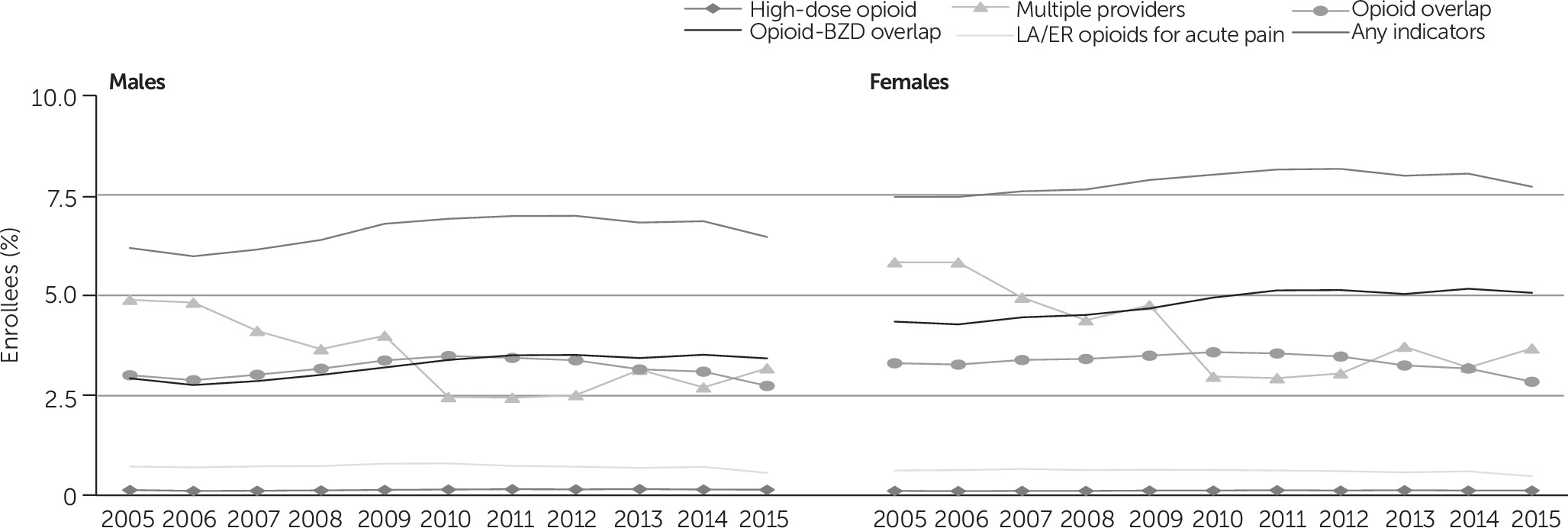

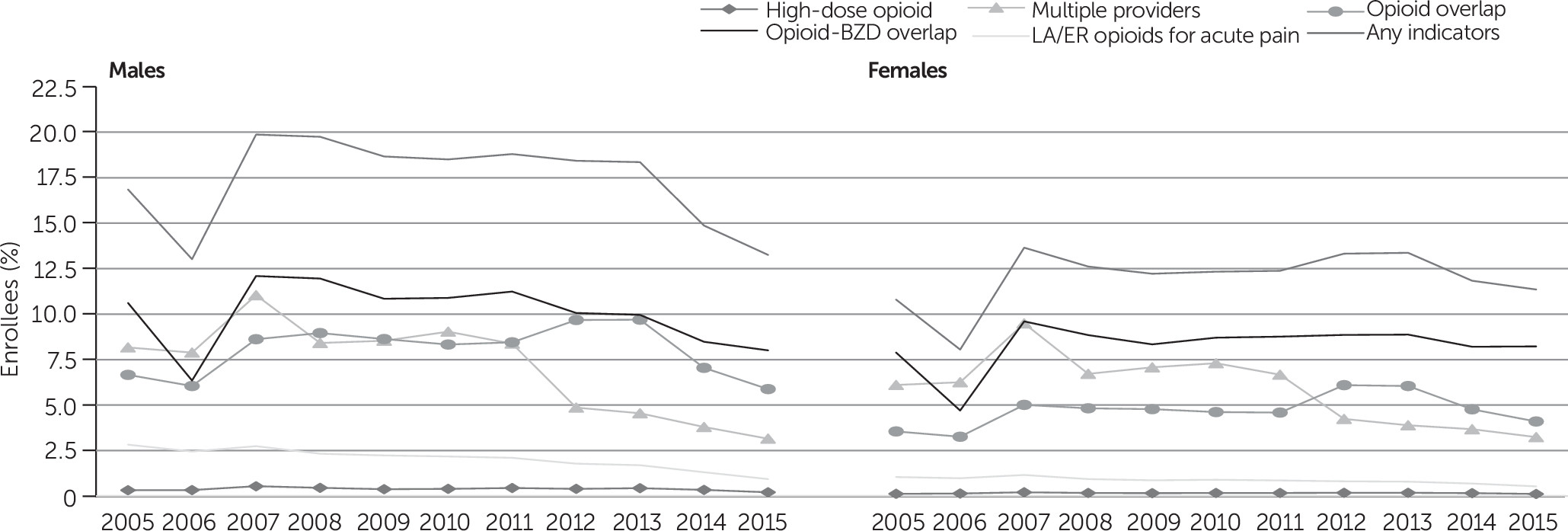

Discussion

Consistent with prior literature (

25,

26), we found that one in 13 enrollees in private insurance and one in seven Medicaid enrollees who were prescribed opioids had at least two indicators of potentially problematic prescriptions that deviated from guidelines. There is a variety of possible explanations for this finding. Medicaid beneficiaries may use different physicians or settings for their care, or they may seek or receive opioids for somewhat different reasons. However, across the decade, potentially problematic prescriptions declined over time and declined more steeply among Medicaid enrollees than among those with private insurance. There was greater room for improvement at the beginning of the study as well as actual improvements in care by 2015, demonstrating that some of these practices may have reduced certain types of problematic prescriptions through policy, educational, or clinical interventions. Our results also revealed variation in rates of problematic opioid prescription by age, sex, health plan type, and race or ethnicity (

33).

Prescriptions for high-dose opioids remained low and relatively stable across the study period for both payer groups, suggesting that prescribers are exercising caution regarding the prescribing of opioids with a high-morphine-milligram-equivalent. The incidence of this practice may be lower than for other prescription practices because of the greater risk of adverse events, including medication side effects (e.g., constipation, drowsiness, nausea, and vomiting) as well as overdose. Some prescription practices were more common at the beginning of the study, including the rate of receiving long-acting opioid prescription for acute pain, but decreased for both Medicaid and privately insured populations. This demonstrates an appropriate move away from long-acting opioids, which are more commonly reserved for chronic pain rather than for acute pain. By contrast, overlapping prescriptions, both for two or more opioids and for opioids and benzodiazepines, was a persistent concern across the study period, with some decline in 2014 and 2015, particularly for opioid overlap prescriptions. Prescribing of high-dose opioids over long periods of time, use of long-acting opioids for acute pain, and overlapping prescriptions are indicators that are potentially within the control of prescribers and can be influenced by public policy initiatives. For example, from August 2016, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration began to require a black box warning label on opioids regarding the dangers associated with concurrent use with benzodiazepines, and an important direction for future research will be investigation of its effect (

34).

The role of patients in potentially problematic prescriptions also was evident in our study. Approximately 5% of privately insured enrollees and 8% of Medicaid enrollees obtained opioids from three or more providers. Opioid seeking from multiple providers is hard to monitor without access to a prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP). Recent literature has shown evidence of a decline in doctor shopping behavior in states where mandatory enrollment in and access to PDMPs are implemented (

35). This finding highlights the importance of PDMPs in preventing potentially problematic opioid misuse.

The differences in rates of problematic opioid prescription behavior across demographic characteristics (especially among Medicaid enrollees) highlight the potential for more targeted interventions and outreach efforts. Recent research has shown an increase in mortality among low-income, middle-aged non-Hispanic whites, largely related to drug overdose, and our results showing a higher prevalence of problematic opioid prescriptions among this demographic group underscores the urgency of addressing this issue (

36).

Our results should be interpreted in light of four limitations. First, we could not directly attribute prescription fills to a specific provider. We linked fills to the provider associated with the most recent relevant encounter. There are many reasons that patients with certain medical needs—particularly older patients—might see multiple providers, often within a short period of time. Not being able to link providers with prescriptions directly is most likely to affect our results regarding the use of multiple prescribers, with the likely effect of overestimating the number and percentage of patients actually obtaining opioids from more than one health care provider. Second, MarketScan includes only adjudicated pharmacy claims instead of actual drug consumption, meaning that there may be more prescription fills than our study revealed (e.g., prescriptions filled where the patient paid with cash), potentially underestimating opioid prescriptions filled. There also may have been fills that were prescribed but were not consumed. Third, this study used only data from private and Medicaid claims, excluding Medicare enrollees, the uninsured, and other payers. Patients who are uninsured are less likely to have adequate medication management, and patients with Medicare are more likely to have multiple health conditions, which may require opioid analgesics. Therefore, a potential implication of this limitation (along with our continuous enrollment requirement, which might exclude at-risk Medicaid patients) is that the rates of inappropriate prescribing reported in this study may be an underestimate. Fourth, other indicators of potentially problematic prescriptions cannot be captured with claims data (e.g., whether the physician reviewed the PDMP when starting opioid therapy and periodically thereafter if opioid therapy continued). Analysis of additional indicators with alternative data sources might be an important area for future work.

Conclusions

Recent literature shows that prescribing of opioids has decreased over the past few years (

37), yet concerns about prescription practices remain. This study shows that indicators of problematic opioid prescriptions remained steady for much of the time period examined but, in some cases, decreased at the end of the study period.

Various policy approaches for limiting problematic opioid prescriptions are ongoing, at both the federal and state levels, but there is still room to expand implementation. Expanding access to PDMPs, which have been documented to reduce opioid related outcomes (

35), and ensuring they have key features that facilitate their use may, in particular, help reduce the number of potentially problematic prescriptions. The 21st Century Cures Act authorized funding for states to deliver a comprehensive approach to expanding opioid use disorder prevention, treatment, and recovery support services, and these activities might play a critical role in combating the opioid crisis (

38).