A stated goal of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was to improve access to community mental health treatment (

1). The combination of Medicaid expansion, individual and employer mandates, and subsidies for low-income people, alongside provisions in the contemporaneous Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act, sought to increase access to insurance coverage and mental health treatment for people with mental illness (

2–

4).

The ACA was thought to be especially important for the millions of community-dwelling individuals involved with the criminal justice system, because of their high rates of mental illness and historically low rates of health insurance coverage (

5–

8). One in seven individuals released from prison has a major depressive or psychotic disorder (

9), and serious psychological distress is five times more common among individuals involved in the criminal justice system, compared with the general population (

10). This high burden of psychiatric disease contributes to high rates of morbidity and suicide-related mortality among individuals with criminal justice involvement (

11–

13). In addition, up to 80% of individuals with a history of criminal justice involvement had no health insurance prior to the ACA (

7).

Criminal justice experts hypothesized that the ACA, and especially the expansion of Medicaid, would provide insurance coverage for more than one-half of community-dwelling individuals with criminal justice involvement (

7,

14,

15). Several studies prior to implementation of the ACA demonstrated that Medicaid enrollment was associated with higher levels of mental health treatment in the general population (

16,

17) and among individuals with criminal justice involvement (

18). Thus, gains in insurance coverage through the ACA were expected to improve access to needed mental health treatment for individuals with criminal justice involvement (

5–

7). Whether rates of mental health treatment indeed changed for individuals involved in the criminal justice system following ACA implementation has not been examined.

The goal of this study was to estimate changes in insurance coverage and use of mental health treatment among individuals involved in the criminal justice system after implementation of the ACA. Although the ACA is associated with improvements in mental health treatment among individuals in the general population (

19,

20), changes in treatment patterns among individuals with criminal justice involvement may differ because the law does not directly address barriers specific to this population, such as stigma in mental health care settings, higher rates of poverty, housing instability, and food insecurity (

21,

22).

Methods

Data

We analyzed data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) from 2011 to 2017. The NSDUH is a nationally representative, cross-sectional survey of noninstitutionalized men and women age 12 years and older (

23). The survey is sponsored by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and conducted by RTI International. The purpose of the NSDUH is to estimate the prevalence of substance use and mental illness in the United States and determine the need for treatment services. Data from approximately 55,000 in-person interviews are included in the annual NSDUH public use file.

Sample

We restricted our main sample to nonelderly men and women ages 19 to 64 with and without criminal justice involvement in the past year who met criteria for serious psychological distress. We focused on nonelderly adults because they represent the intended target population of the ACA’s key provisions to expand health insurance coverage (i.e., Medicaid expansion and marketplace plans). We conducted the analysis among those with serious psychological distress (score of ≥13 on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale [K6]), because they are likely to be in need of mental health treatment (

24). The K6 is a validated, six-item inventory utilized as a screening tool to detect serious mental illness in the general population; a score of 13 or greater has specificity of 0.96 and sensitivity of 0.36 for serious mental illness (

24).

Independent Variable

We determined criminal justice involvement in the past year if respondents reported being arrested and booked in the past year (excluding minor traffic violations) or under community supervision via probation or parole in the past year.

Dependent Variables

We categorized respondents as insured if they were enrolled in a private or public health insurance plan at the time of the interview. We also created mutually exclusive health insurance categories. Those enrolled in any private plan were categorized as having private insurance, and those enrolled in Medicaid, but not a private plan, were categorized as having Medicaid. Individuals not enrolled in either Medicaid or a private plan were labeled as “other.”

Study measures of mental health treatment were based on self-report. We created binary variables for receipt of any mental health treatment, any inpatient mental health treatment, any outpatient mental health treatment, and any mental health prescription medication. We categorized payment for mental health treatment as private insurance, Medicaid, self-payment/uninsured, or “other.” Participants were categorized as having unmet mental health treatment need if there was any time in the past 12 months during which they reported needing mental health treatment but did not receive it. Receipt of any mental health treatment and having unmet mental health needs were not mutually exclusive categories. Among individuals who indicated unmet need, we estimated the proportion who reported insurance coverage or the affordability of treatment as a perceived barrier.

Covariates

We adjusted for participant age, gender, race–ethnicity, urban or rural location, marital status, and poverty level in our models. We categorized participants’ age into the following groups: 19–25, 26–34, 35–49, and 50–64. Gender categories were based on self-report, and individuals were categorized as either male or female. Race-ethnicity categories included non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic white, or other. Rural or urban county of residence was defined by using rural-urban continuum codes (

25). Marital status was categorized as either married or nonmarried. We used the three federal poverty levels available in the NSDUH public use file: living below 100% federal poverty level, living at more than 100% but less than 200% federal poverty level, and living above 200% federal poverty level.

Statistical Analysis

Among nonelderly adults with serious psychological distress, we estimated weighted proportions of those with and without past year criminal justice involvement and compared differences in weighted proportions of baseline sociodemographic characteristics between the groups. We tested differences by using the chi-square test statistic.

To compare changes in health insurance coverage and mental health treatment over time, we divided the sample into two time periods: 2011–2013 and 2014–2017. These represent the time periods prior to and after implementation of the ACA’s key health insurance expansion provisions (Medicaid expansion and marketplace plans) (

26). We aggregated responses into discrete time periods to allow for sufficient statistical power to assess trends following ACA implementation. Among individuals with and without criminal justice involvement in the past year, we calculated the proportion of individuals who were insured or received any mental health treatment in each time period. We compared differences in outcomes between each time period by using multivariable logistic regression. In these models, we created an interaction term for time period (pre- or post-ACA) × criminal justice status. We then used predictive margins to generate adjusted estimates of health insurance coverage and mental health treatment for individuals with and without criminal justice involvement in the past year for the periods before and after ACA.

We further assessed changes in receipt of various types of mental health services (inpatient services, outpatient services, or prescription medication) and source of payment for mental health treatment. We also assessed unmet mental health needs regardless of receipt of any mental health treatment. For those with unmet mental health needs, we examined the proportion who reported coverage and cost-related concerns as a barrier to care.

To assess the robustness of study findings, we conducted sensitivity analyses among individuals more likely to be affected by implementation of the ACA, namely those living at or below 200% federal poverty level, and among individuals with any mental illness or with serious mental illness.

All analyses were adjusted for the covariates described earlier unless otherwise specified and accounted for in the complex survey design of the NSDUH. We utilized person-level survey weights developed by the Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality to provide estimates that were representative of the noninstitutionalized U.S. population. All data were analyzed by using Stata/SE, version 15.1. Two-sided p values of <.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

The unweighted, pooled sample consisted of 14,044 individuals who reported criminal justice involvement in the past year, representative of approximately 7.8 million nonelderly U.S. adults annually, and 232,946 who reported no criminal justice involvement in the past year, representative of approximately 181.2 million individuals annually. Among individuals with past-year criminal justice involvement, 3,688 (25.4%, 95% confidence interval [CI]=24.4–26.4) met criteria for serious psychological distress across all survey years and were representative of 2.0 million individuals annually. Among individuals with no criminal justice involvement in the past year, 33,872 (11.5%, 95% CI=11.3–11.7) met criteria for serious psychological distress across all survey years, representative of 20.9 million individuals annually.

Among individuals with serious psychological distress, there were statistically significant differences in sociodemographic characteristics between individuals with and without criminal justice involvement in the past year (

Table 1). Individuals with criminal justice involvement in the past year were more likely to be younger, be male, be black or Hispanic, live in a rural county, be unmarried, have incomes below 200% of the federal poverty level, and have a higher K6 score.

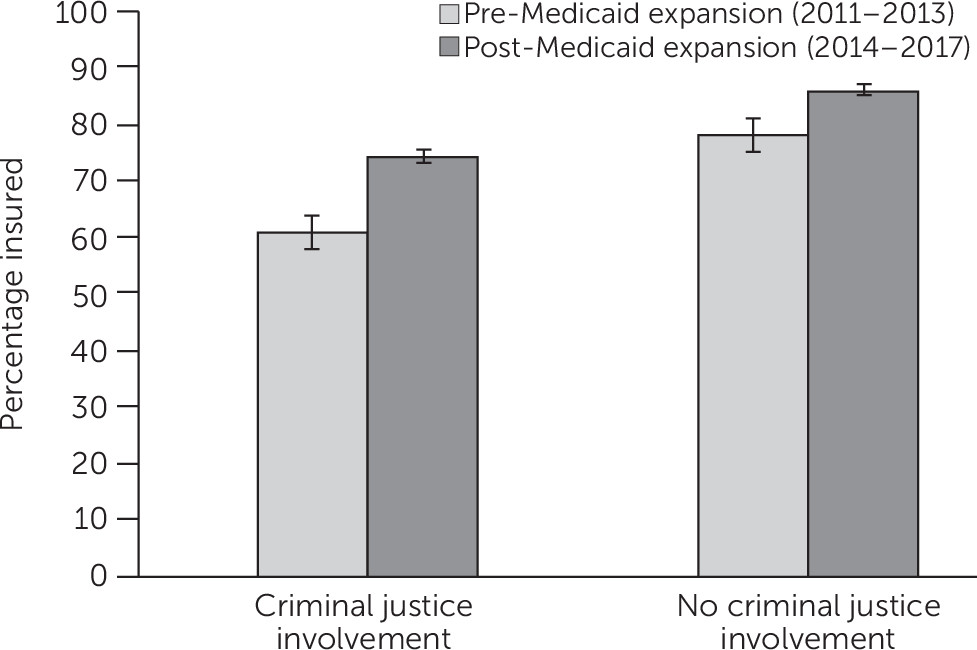

Insurance Coverage

Following implementation of Medicaid expansion, the employer mandate, and private health insurance exchanges, the proportion of individuals who had insurance coverage increased significantly among those who reported criminal justice involvement in the past year (increase of 13.4 percentage points (95% CI=8.5–18.3), from 61.0% (95% CI=56.7–65.2) in 2011–2013 to 74.4% (95% CI=71.8–77.1) in 2014–2017 (

Figure 1). Among individuals with no criminal justice involvement in the past year, there was a statistically significant increase of 8.1 percentage points (95% CI=6.9–9.4) in the proportion of individuals who had insurance coverage, from 78.0% (95% CI=77.0–79.0) in 2011–2013 to 86.1% (95% CI=85.4–86.9) in 2014–2017 (

Figure 1). Insurance coverage increased to a greater degree among individuals with criminal justice involvement, compared with the general population (difference-in-differences estimate=3.6 percentage points, 95% CI=–0.4 to 7.8).

Following ACA implementation, the proportion of individuals with criminal justice involvement in the past year who had Medicaid insurance increased significantly from 25.4% to 37.4%, a difference of 12.0 percentage points (95% CI=7.2–16.7). Also, there was a significant, although smaller, increase in the proportion of individuals with criminal justice involvement who had private insurance, from 24.0% to 28.7%, a difference of 4.7 percentage points (95% CI=0.5–8.9). These changes were similar to those seen in individuals who had no criminal justice involvement in the past year. (A table showing these data is available in an online supplement to this article.)

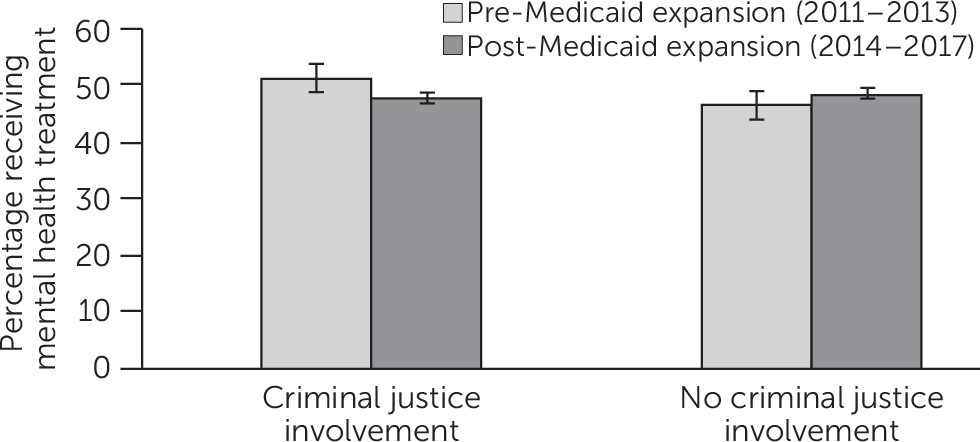

Mental Health Treatment

Among adults with past-year criminal justice involvement, there was no significant change in receipt of any mental health treatment following ACA implementation (from 50.7% [95% CI=47.3–54.2] in 2011–2013 to 47.3% [95% CI=44.0–50.6] in 2014–2017, a difference of –3.4 percentage points [95% CI=−8.0 to 1.1]) (

Figure 2). Among individuals with no past-year criminal justice involvement, there was a significant increase of 2.2 percentage points (95% CI=0.4–3.9) in receipt of any mental health treatment after implementation of the ACA (from 45.7% [95% CI=44.1–47.2] in 2011–2013 to 47.9% [95% CI=46.9–48.8] in 2014–2017).

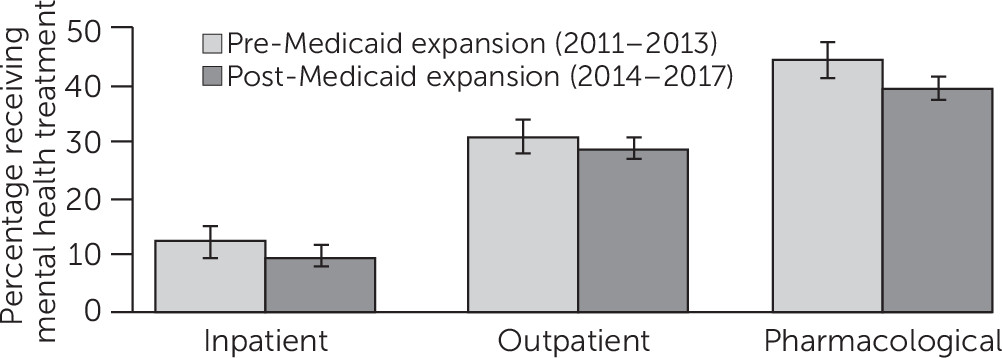

Among individuals with criminal justice involvement in the past year there were no changes in the proportion reporting any inpatient mental health treatment (−2.5 percentage points [95% CI=−5.7 to 0.5]), outpatient mental health treatment (−2.0 percentage points [95% CI=−6.2 to 2.2]), or receipt of prescription medication for a mental disorder (−4.6 percentage points [95% CI=−9.0 to 0.2]) (

Figure 3). Conversely, among individuals with no criminal justice involvement in the past year, we found significant increases in the proportion reporting any outpatient mental health treatment (2.0 percentage points [95% CI=0.2–3.8]) and receipt of prescription medication for a mental disorder (1.8 percentage points [95% CI=0.1–3.4]). (Details are available in the

online supplement to this article.)

Barriers to Mental Health Treatment

There was no change in the proportion of individuals with unmet mental health care needs following ACA implementation among individuals with criminal justice involvement in the past year (33.1% in 2011–2013 and 32.2% in 2014–2017, a difference of –0.8 percentage points [95% CI=−5.4 to 3.6]). Among those who reported an unmet mental health need, there was a decrease in those reporting that they did not get care because of financial reasons (i.e., cost, lack of insurance coverage, or insurance not paying enough for treatment) (61.3% in 2011–2013 and 49.0% in 2014–2017, a difference of –12.3 percentage points [95% CI=−4.4 to –20.1]). These changes were similar to those seen in individuals with no criminal justice involvement in the past year. (Details are available in the online supplement to this article.)

Mental Health Treatment Payer

There was no statistically significant change in payers for mental health treatment after ACA implementation among individuals with criminal justice involvement in the past year. Those reporting that Medicaid paid for their mental health treatment increased, but not to a statistically significant degree, from 25.3% to 29.9% (a difference of 4.5 percentage points, 95% CI=−3.4 to 12.5). In addition, the proportion that reported their mental health treatment was paid for by themselves or their family members decreased, but not to a statistically significant degree, from 26.8% to 23.4% (a difference of –3.4 percentage points, 95% CI=−10.0 to 3.3). There were no changes in the proportion of individuals who reported that private insurance paid for their mental health treatment following Medicaid expansion. These changes were similar to those seen in individuals with no criminal justice involvement in the last year. (Details are available in the online supplement to this article.)

Sensitivity Analyses

Among individuals with past-year criminal justice involvement who were living at or below 200% of the federal poverty level, who had any mental illness or who had serious mental illness, changes in health insurance coverage and mental health treatment were substantively similar to the findings of our primary analysis. (Details are available in the online supplement to this article.)

Discussion

Among a nationally representative sample of nonelderly adults with psychological distress who were involved in the criminal justice system, we found that insurance coverage increased substantially following implementation of the ACA’s key provisions, largely driven by increased Medicaid enrollment. The changes in health coverage we found may partially be attributable to efforts among some jails, prisons, and community organizations to enroll individuals with criminal justice involvement in Medicaid (

27–

29).

However, despite large gains in health insurance coverage, there was no change in the proportions receiving any mental health treatment or reporting unmet mental health needs. This is in contrast to the general population, where implementation of the ACA was associated with an increase in mental health treatment, a finding also demonstrated in this study (

19,

20,

30). When taken together with previous work indicating that the ACA is not associated with changes in substance use treatment for individuals with criminal justice involvement, we conclude that behavioral health treatment for individuals with criminal justice involvement did not increase after ACA implementation (

31). Although insurance coverage increased, mental health service availability may not be sufficient to meet the demand for treatment among this population (

32,

33). Furthermore, the intensity of mental health treatment may not be adequate to alleviate perceptions of unmet treatment need (

34).

Absence of a detectable change in the proportion accessing mental health treatment may also reflect unique barriers to mental health treatment for this high-need population. Compared with the general population, individuals with criminal justice involvement experience higher rates of poverty, housing instability, and food insecurity, often exacerbated by policies that limit social services for those with specific felony convictions (

21). These competing demands may take priority over accessing mental health services (

35–

39). In addition, previous negative experiences, stigma, and structural discrimination within the health care system create mistrust and have been shown to affect the experience, quality, and acceptability of mental health care among individuals with criminal justice involvement (

22,

37–

39).

Care coordination or clinical settings tailored to the needs of people with criminal justice involvement may be promising tools to bridge the gap between health insurance and mental health treatment among individuals with criminal justice involvement (

40–

44). Implementation of these specialized programs is complicated by a federal law that prohibits the use of Medicaid during incarceration (

18), which interferes with continuity of care during transition to the community. Revision of the Medicaid inmate exclusion would facilitate expansion of models that coordinate services across state Medicaid agencies, criminal justice systems, and mental health treatment providers.

Although the primary goal of our study was to examine the association between the ACA and mental health treatment changes among individuals with criminal justice involvement, it is important to note that mental health treatment among people with and without criminal justice involvement was similar in the post-ACA period. We anticipated mental health treatment would be higher in people with criminal justice involvement, because, among those with psychological distress, individuals with criminal justice involvement had a higher mean K6 score and a larger proportion would have likely been mandated by courts to receive treatment. It is possible there is a ceiling effect that caps the level of mental health treatment in the community, and, therefore, it is difficult to increase treatment levels despite increasing coverage.

There were important limitations to our study. The NSDUH is a cross-sectional survey, and, therefore, we could not elucidate a temporal relationship between mental health treatment and criminal justice involvement. The NSDUH is a household survey of noninstitutionalized individuals and excludes people who are homeless or currently incarcerated. These exclusions may lead to a relative underrepresentation of individuals involved in the criminal justice system (

45). Although criminal justice involvement is measured with a heterogeneous set of indicators in the NSDUH, estimates of community supervision in the NSDUH are generally similar to other national data sources (

46). Because information is limited to past-year arrest, lifetime arrest, and parole and probation, we were unable to determine the degree of justice involvement and lifetime history of incarceration, a level of granularity that should be pursued in future studies. Criminal justice involvement, insurance coverage, and mental health treatment in the NSDUH are based on self-report and, as in any survey, are susceptible to recall bias.

Conclusions

Despite substantial increases in health insurance coverage for individuals with serious psychological distress and criminal justice involvement, mental health treatment did not change following implementation of the ACA. Our findings highlight that health insurance coverage is a necessary, but not sufficient step to increase needed mental health treatment for individuals involved in the U.S. criminal justice system. Future work should address the persistent barriers that hinder access to mental health treatment for this high-need, vulnerable population.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the faculty and colleagues at the Yale National Clinician Scholars Program, who provided thoughtful and constructive feedback on this project during its development.