Psychotic disorders affect many areas of life—including educational, social, and occupational functioning (

1–

4)—and they are associated with increased suicide risk. Studies of long-term outcomes in psychosis, primarily nonaffective psychosis, indicate that early detection and intervention lead to improved outcomes for individuals with psychotic disorders (

5–

12).

The RAISE (Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode) research initiative supported the development of coordinated specialty care (CSC) programs for first-episode psychosis (FEP) in community clinics (

13). This research led to the development of statewide community-based programs, such as OnTrackNY in New York State (NYS), which utilize a CSC model for people who are experiencing early, nonaffective psychosis (

11,

14,

15).

Traditionally, Medicaid plays a significant role in financing behavioral health services (

16). However, that is less true for individuals experiencing FEP, who tend to be younger and not insured (

17). The recent Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and federal policy initiatives focused on coverage of early intervention services for FEP, and these initiatives are expected to increase Medicaid coverage of individuals with behavioral health needs, including those experiencing FEP (

16). In NYS, for example, changes in Medicaid programs and policy require the identification of Medicaid members with FEP and linkage of these members to CSC services, including OnTrackNY (

18–

20).

Population-based approaches to identify individuals experiencing FEP are needed to support these initiatives. A recent population-based approach used insurance claims to determine the incidence of psychotic symptoms among persons ages 15 to 29 (86 per 100,000) and ages 30 to 59 (46 per 100,000) (

21). The study was not likely representative of individuals receiving services in the public mental health system, given that only 10% were insured through Medicaid or Medicare (

21). In addition, the inclusion of the 30–59 age group may be too broad, given that the typical age of onset for schizophrenia is late adolescence or early twenties, with a slightly later onset in females (

22).

We describe a retrospective, population-based study of first diagnosis of psychosis in the NYS Medicaid program. The primary aim of this study was to estimate FEP incidence rates in a Medicaid sample by adapting a previously published method that used administrative data for estimating FEP incidence (

21). Secondary aims were to examine demographic and service patterns related to first psychosis diagnosis in Medicaid and to utilize record review to validate the algorithm and estimate the adjusted incidence of FEP and settings of FEP presentation in a Medicaid population.

Methods

The NYS Medicaid billing and encounter data system (Medicaid) was used to identify patients with new onset of psychosis during the 5-year period between January 1, 2013, and December 31, 2017. Psychosis was defined as having at least one claim or encounter for an outpatient or inpatient service with the following diagnoses: schizophrenia spectrum disorders (ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes 295.0–295.9 and F20.0–F20.9), affective psychosis (296.04, 296.14, 296.24, 296.34, 296.44, 296.54, 296.64, F30.2, F31.2, F31.5, F31.64, F32.3, and F33.3), and other psychotic disorders (297.1, 297.3, 298.8, 298.9, F21–25, F28, and F29). Diagnoses of substance-induced psychosis were not included as qualifying first-episode diagnoses.

The study population referred to as “putative cases” was limited to individuals between the ages of 15 and 35 at the time of diagnosis with no prior Medicaid claims or encounters for service for psychosis. The prior-service lookback period was inclusive of 13 years prior to the study period (2000–2012) where data were available. Finally, the study population was limited to those continuously enrolled in Medicaid for at least 12 months prior to the first identified diagnosis. Individuals with dual eligibility for Medicare and Medicaid were excluded.

Demographic and service-related characteristics of putative cases were extracted from Medicaid. Demographic characteristics (age, gender, and race-ethnicity) were categorized as follows: age at first presentation (15–25 versus 26–35), gender (male or female), and race-ethnicity (non-Hispanic white; racial-ethnic minority, including non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and other; or unknown). Service-related characteristics were categorized as follows: service setting at first presentation (behavioral health–related emergency or inpatient setting, nonbehavioral health–related emergency or inpatient setting, outpatient behavioral health specialty setting, or outpatient general setting), indication of any antipsychotic medication fill prior to first diagnosis, and Medicaid program type (managed care or fee for service [FFS]).

Annual crude incidence rates (IRs) were calculated for demographic and service-related characteristics as the number of putative cases per year divided by the number of Medicaid recipients continuously enrolled during calendar year 2015, yielding an estimate of annual incidence (putative cases per 100,000 persons per year). Stratified analyses were conducted for age at first diagnosis (15–25 versus 26–35) and for demographic and service-related characteristics. Poisson distribution models were used to estimate IRs of psychosis for the two age groups by demographic and service-related characteristic and compare the results by using rate ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) (

23,

24).

The OnTrackNY data system was used to confirm putative cases as FEP and to compare date of onset of psychosis with the first service date in Medicaid. The OnTrackNY data system collects participant-level, clinician-reported standardized assessments over the course of care. Medicaid ID and date of onset of psychosis were extracted for Medicaid-enrolled OnTrackNY recipients. The OnTrackNY sample was matched to putative cases for confirmation of identity and to compare date of first presentation with psychosis in Medicaid with the first onset of psychotic symptoms recorded by OnTrackNY.

Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) were invited to assist in validation of the algorithm. Three managed care entities (MCEs) agreed to participate, including nine MCOs represented by one behavioral health organization (BHO) and two MCOs. These MCEs represent 65% of the state’s MCE plans (11 of 17 plans) and 53% of the lives covered by Medicaid managed care statewide in 2017. These organizations agreed to participate in a chart review of putative cases identified by the algorithm for calculation of adjusted IRs. MCEs use NYS guidelines to implement FEP-identification protocols that include reviewing individual clinical records (

15,

18,

19).

A random sample of 50 cases from each entity was selected for review. Entities completed a tool to confirm putative case identity (Medicaid ID, name, date of birth, and Social Security number) and to indicate confirmation or nonconfirmation of FEP diagnosis and date. Cases were categorized as confirmed if plan records identified the member as having FEP via an algorithm or via clinical assessment. Reasons for nonconfirmation were documented as diagnostic rule-out (records indicate psychotic diagnosis was ruled out rather than confirmed); not continuously enrolled in plan; or other.

Adjusted IRs were calculated by age group and service setting by using the number of putative cases identified and confirmation rates. The 95% CIs for confirmation rates were estimated without continuity correction (

25). Initial estimated IRs (based on putative cases) were multiplied by confirmation rates (confirmed cases divided by putative cases) to yield final estimates of adjusted IRs in each stratum.

This study protocol was approved by the Nathan S. Kline Institute Institutional Review Board with a full waiver of informed consent. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS software, version 9.4 (

26).

Results

Incidence of FEP in Medicaid

This study identified 62,470 individuals ages 15 to 35 who were first diagnosed as having any psychotic disorder during the study period (2013–2017). Excluding individuals with dual eligibility for Medicare and Medicaid reduced the sample to 59,719 individuals. Selected individuals were further limited to those continuously enrolled in Medicaid for at least 1 year prior to the first diagnosis date. The final study population consisted of 31,606 individuals with a psychosis diagnosis that was first recorded during the 5-year study period.

Table 1 displays the distribution of FEP cases by demographic and service characteristic. The first recorded diagnosis was schizophrenia spectrum in 21% of cases, other psychosis in 48%, and affective psychosis in 31% (

Table 1). In terms of service category, the largest proportion of cases involved individuals who were identified in specialty mental health outpatient settings (44%), followed by individuals identified in acute behavioral health inpatient or emergency room settings (38%). In 62% of cases, individuals had an antipsychotic medication fill prior to the first diagnosis (

Table 1).

Table 2 displays crude IRs and age-stratified IRs for putative cases in Medicaid of FEP by demographic and service characteristics; the RRs of putative cases by age for each demographic and service characteristic are also displayed. The overall IR was 454 per 100,000 in this Medicaid population. The rate was highest for enrollees in Medicaid FFS (IR=856), males (IR=517), and nonwhites (IR=503).

Age-stratified rate comparisons revealed significantly lower IRs in the younger age group (15–25) relative to the older age group (26–35) for males (RR=.926), for those with a first-diagnosis type of schizophrenia spectrum (RR=.885) or affective psychosis (RR=.934), for those with a first service setting of outpatient behavioral health specialty (RR=.902), and for those with a prior antipsychotic fill (RR=.853) (

Table 2). Significantly higher IRs were found in the younger age group (15–25) relative to the older age group (26–35) for those with a first-diagnosis type of other psychosis (RR=1.111), for those with a first service setting of acute behavioral health emergency or inpatient facility (RR=1.286), and for those covered by FFS Medicaid (RR=1.508) (

Table 2).

OnTrackNY Confirmation of FEP and Date of Onset

The OnTrackNY data system was used to identify enrolled individuals with Medicaid insurance during the study period (N=493 of 1,024 total OnTrackNY clients, 48%). Matching putative cases to Medicaid-insured OnTrackNY clients revealed that 42% (N=208) of the OnTrackNY clients were identified by the Medicaid algorithm as putative cases. A much higher match rate (N=446, 90%) was found when 1 year of continuous Medicaid eligibility was removed as a selection condition for putative cases.

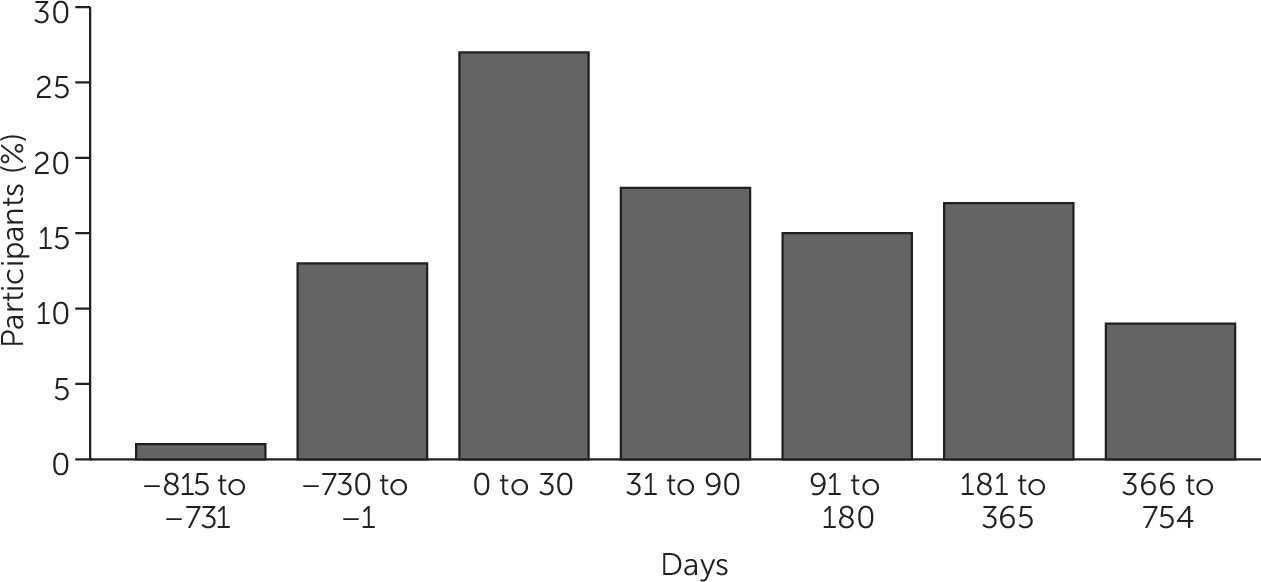

Date of first psychosis diagnosis identified by the Medicaid algorithm and date of onset of psychosis recorded in OnTrackNY were compared for individuals for whom both dates were available (N=440). Of putative cases identified by the algorithm, the majority (45%) were identified within 3 months after the onset date indicated in OnTrackNY, another 32% were identified within a year after the OnTrackNY onset date, and a small percentage (9%) were identified within 2 years after the OnTrackNY onset date. For approximately 14% of putative cases, the first-episode date identified by the algorithm was earlier than the first-onset date indicated in OnTrackNY (

Figure 1).

Estimation of Adjusted IRs For FEP

The three MCEs participated in a chart review of a random sample of 50 members from each entity who were identified by the algorithm as putative cases (N=150). Selected cases were diagnostically representative of the underlying sample: affective psychosis (N=52, 35%) and schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders (N=98; 65%). MCEs completed a data sheet including relevant information on the putative cases (data collection tool available upon request). The selected MCEs were asked to confirm putative cases through in-depth review of plan records.

MCEs confirmed 66% (N=65) of the putative cases of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders and 48% (N=25) of putative cases of affective psychosis, for an overall confirmation rate of 60% (N=90). The remaining 40% (N=60) of cases were not confirmed as FEP for several reasons: the individual’s diagnosis was not included as FEP in the plan’s algorithm (N=34; 21 related to an affective psychosis diagnosis and 13 related to schizophrenia and other psychotic diagnoses); the individual was eligible for the plan for less than 1 year (N=15); or other (N=11). Confirmation rates across age groups and service settings are presented in

Table 3.

The stratum-specific confirmation rates provided by the MCEs were used to estimate adjusted annual IRs per 100,000 individuals by age group and service setting (

Table 4). The adjusted annual IR was higher for ages 15–25 relative to ages 26–35 in behavioral health–related emergency or inpatient settings and in outpatient specialty settings. In outpatient general medical services and nonbehavioral health emergency department or inpatient services, the adjusted IR was higher for ages 26–35 compared with ages 15–25 (

Table 4).

Discussion

This study adapted a previously published population-based algorithm to identify first presentation of psychosis in Medicaid (

21). In this Medicaid population–based study, we estimated the actual IR of first diagnosis of psychosis to be 272 per 100,000 per year. This rate is higher than the rate estimated by the replicated study, in which a majority of the population was privately insured (

21). Both this study and the replicated study estimated higher IRs relative to studies using clinical case identification methods (

27–

29). Higher IRs in a Medicaid population are not surprising, given ample research demonstrating a relationship between lower socioeconomic status and psychosis (

30–

34).

In terms of its ability to identify a younger population prior to accumulation of significant disability related to psychosis, the importance of this algorithm should not be underestimated. Compared with individuals with a serious mental illness in the Medicaid system (

35), the individuals identified as putative cases by this algorithm were less disabled. In addition, this analysis should alert the Medicaid program to examine the need for FEP services in the populations that were carved out of Medicaid managed care but that remain covered by FFS Medicaid (

36). These populations may include individuals who are enrolled in or who have a history of being in the child welfare system, who have intellectual disabilities, or who have other chronic health needs. In this study, the group covered by FFS Medicaid had a higher crude IR of FEP compared with the group covered by Medicaid managed care. This high crude IR for the population covered by FFS Medicaid may point to disparities in need for FEP services for populations excluded or excepted from Medicaid managed care (

37).

This study also supports continued work to develop CSC models that are more broadly inclusive of the population in need, including those experiencing affective psychosis or those with a comorbid substance use disorder. It also points to a potential demand based on estimated adjusted IRs that exceeds capacity (

38,

39). That said, we utilized broad inclusion criteria to support planning related to early intervention programs. Case definitions in both this study and the previous study included patients with new claims for any of a broad set of psychosis diagnoses (

21). It is possible that individuals with a co-occurring substance use disorder or co-occurring mood disorder were included as cases in the sample and that these individuals may later be clinically determined to have substance or mood disorders rather than schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Clinically it is known that initial diagnostic classification among schizophrenia disorders changes over time; however, more work needs to be done to understand the stability of psychosis diagnosis in insurance claims (

40).

In addition, this study indicates that programs focusing on outpatient mental health and acute settings would identify many of the incident cases. Programs like NYC START may have important potential to identify incident cases of FEP in acute settings, a critical point in the presentation of early psychosis (

41). However, FEP case identification methods likely need to be enhanced in outpatient mental health settings as well.

Translating this algorithm from research to practice is an important next step. This will require additional epidemiologic research on the algorithm and operational work to pilot outreach, case confirmation, and treatment planning for identified individuals. Preliminary conclusions using OnTrackNY case confirmation indicate that the algorithm has high sensitivity, provided continuous eligibility (CE) requirements are relaxed. However, given the findings of high crude and adjusted IRs, it is likely that improving the specificity and reducing false positives identified by the algorithm may also be required. As mentioned previously, having Medicaid MCO-reported data on cases of FEP will allow us to conduct sensitivity analyses on the algorithm. The critical areas to examine include the window of CE prior to first diagnosis and the definition of a qualifying diagnostic event or set of events. Currently the qualifying event is one diagnosis of psychosis following a clean period with CE of 12 months. Criteria that can be modified are the number and type of events, time windows between events, and windows of CE prior to the defined events. In this study, individuals in the majority of identified cases had an antipsychotic prescription fill prior to the first psychosis diagnosis. Research to examine the weighting of events by type could lead to a more robust case definition and allow inclusion of less specific information, such as psychotropic medication fill. Next steps in terms of piloting an operational approach to outreach to identified individuals will be planned with the state Medicaid and state mental health authorities, Medicaid MCOs, and service providers. Care will be needed to address privacy issues for these individuals.

We should acknowledge some important study limitations. First, the algorithm identified putative cases by only one claim for psychosis in primary or secondary positions in Medicaid and 1 year of CE in Medicaid prior to this claim. Imposing a CE criterion on a sample derived from insurance is a method used commonly to provide a sample with an equal opportunity to be included in a measure (

42). In this study, a 1-year window of CE was used for purposes of comparing results with the previous study (

21). It is likely that this study missed individuals who qualified for Medicaid for a shorter duration prior to a first-presentation diagnosis. Second, it is possible that the single identifying claim was a rule-out diagnosis rather than a clinical assessment of psychosis. These limitations could both over- and underestimate the true incidence and as such will be important factors to examine in future work to refine the algorithm.

Third, individuals who did not present for treatment are not captured in the algorithm estimate. That would be expected to underestimate true incidence in the population. However, such individuals may be identified in the algorithm as symptoms escalate and care is required. Fifth, the adjusted IR calculations were based on record review by plans that agreed to participate. The record review was a time burden on MCEs, so the state could not randomly assign the task. However, the participating plans represent a majority of lives covered by the state’s Medicaid managed care plans, and these plans are expected to follow guidance provided by the state Medicaid authority for the definition of FEP (

18–

20). As such, the adjusted IR calculations in this study may miss individuals who are covered by other MCOs or who are in FFS Medicaid. In 2019, MCOs are required to submit all first-episode cases to the state for review and oversight. Future work will include these data for calculating adjusted incidence rates.

Conclusions

This study has important implications for the public mental health system. This algorithm presents a mechanism to identify a high-risk population before individuals accumulate significant disability. A comprehensive system for outreach, assessment, and treatment for FEP can be appropriately resourced by using these estimates. Additional research is needed to fine-tune this administrative data algorithm for use as a basis for communication and active outreach by early intervention programs.