There is evidence for a bidirectional link between mental health conditions and obesity, which is likely affected by a host of biopsychosocial factors (

1–

7). For example, mental health status may contribute to obesity via emotional eating, neuroendocrine factors, or obesogenic psychotropic medications. Conversely, obesity may contribute to mental health status through physical disability and weight stigma. The limited existing work suggests that rates of depressive disorders and anxiety disorders are higher among people with obesity versus without obesity, particularly for women (

5,

7). However, there is a critical gap in understanding differences in the rates of other mental health conditions, such as psychotic disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), among people with and without obesity.

Veterans Health Administration (VHA) data are ideal for comparisons of mental health diagnosis rates among people with and without obesity. Among the six million veterans using VHA, over 40% have obesity (

8). VHA is also the largest integrated health care system in the United States and has a diverse patient population. Further, roughly 95% of VHA patients are weighed annually (

9), and VHA administrative data provide national, population-level information on a wide range of mental health conditions (

10).

Our objective was to examine rates of psychiatric diagnoses among a national cohort of VHA primary care patients with and without obesity. All analyses were sex stratified, given that women veterans who use VHA are generally younger, are more racially and ethnically diverse, and have higher rates of psychiatric and physical health diagnoses than men veterans who use VHA (

10). A better understanding of similarities and differences in psychiatric diagnosis rates between people with and without obesity will help guide clinical practice, research, and policy for the delivery of weight management and mental health care.

Methods

The national study cohort used VHA administrative data and comprised all veteran primary care patients who used VHA primary care services in fiscal year 2014 (October 2013–September 2014) and who had a body mass index (BMI)≥18.5 kg/m

2. Unless otherwise noted, additional information, including details on specific

ICD-9 codes, is available elsewhere (

10). This work was approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board.

Psychiatric diagnoses included those related to depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, and PTSD; alcohol use and drug use disorders; psychotic disorders (e.g., schizophrenia); and other psychiatric diagnoses (e.g., eating disorders and personality disorders). The presence or absence of diagnoses was based on fiscal year 2014

ICD-9 diagnosis codes in VHA inpatient care, ambulatory care, and VHA-purchased community care (

10).

We initially categorized patients by obesity status (no obesity, BMI<30 kg/m

2; obesity, BMI≥30 kg/m

2). Follow-up analyses used the following categories: normal weight (18.5 kg/m

2≤BMI<25 kg/m

2), overweight (25 kg/m

2≤BMI<30 kg/m

2), obesity class 1 (30 kg/m

2≤BMI<35 kg/m

2), obesity class 2 (35 kg/m

2≤BMI<40 kg/m

2), and obesity class 3 (BMI≥40 kg/m

2). BMIs were based on a previously developed algorithm that draws upon centralized VHA vital signs data collected during routine clinical encounters. This approach calculates BMI using modal height and the weight taken closest to the patient’s first primary care appointment in fiscal year 2014 (

8).

Sex, age, and race-ethnicity information came from VHA administrative data.

We used descriptive statistics to assess the proportion of patients with any psychiatric diagnosis, using a chi-square analysis to assess sex differences (α=0.001). Next, in sex-stratified analyses, we used descriptive statistics to assess rates of any psychiatric diagnosis and specific diagnoses by obesity status (no obesity [BMI<30 kg/m2] versus obesity [BMI≥30 kg/m2]). Then, we used separate, sex-stratified chi-square analyses to assess rates of any and specific psychiatric diagnoses by obesity status (α=0.001). Finally, we used descriptive statistics to assess rates of any and specific psychiatric diagnoses within more granular weight categories by sex. Because of the large sample size, there was a high likelihood of statistically significant chi-square tests. Therefore, we considered an absolute difference of ≥5% as indicating clinical significance for analyses with the composite variable, any psychiatric diagnosis, but report smaller differences for specific diagnoses, given their relatively low frequency.

Results

The cohort included 342,262 women (44.2% with obesity) and 4,524,787 men (41.7% with obesity). Mean BMI was 29.9±6.5 among women and 29.7±5.7 among men. Mean age was 48.1±14.9 years for women and 63.0±15.4 years for men. Roughly 55.5% of the women and 71.0% of the men were white, 28.9% of the women and 14.8% of the men were black or African American, and 6.5% of the women and 5.6% of the men were Hispanic. A greater proportion of women than men had any psychiatric diagnoses (52.0% vs. 36.3%, p<0.001).

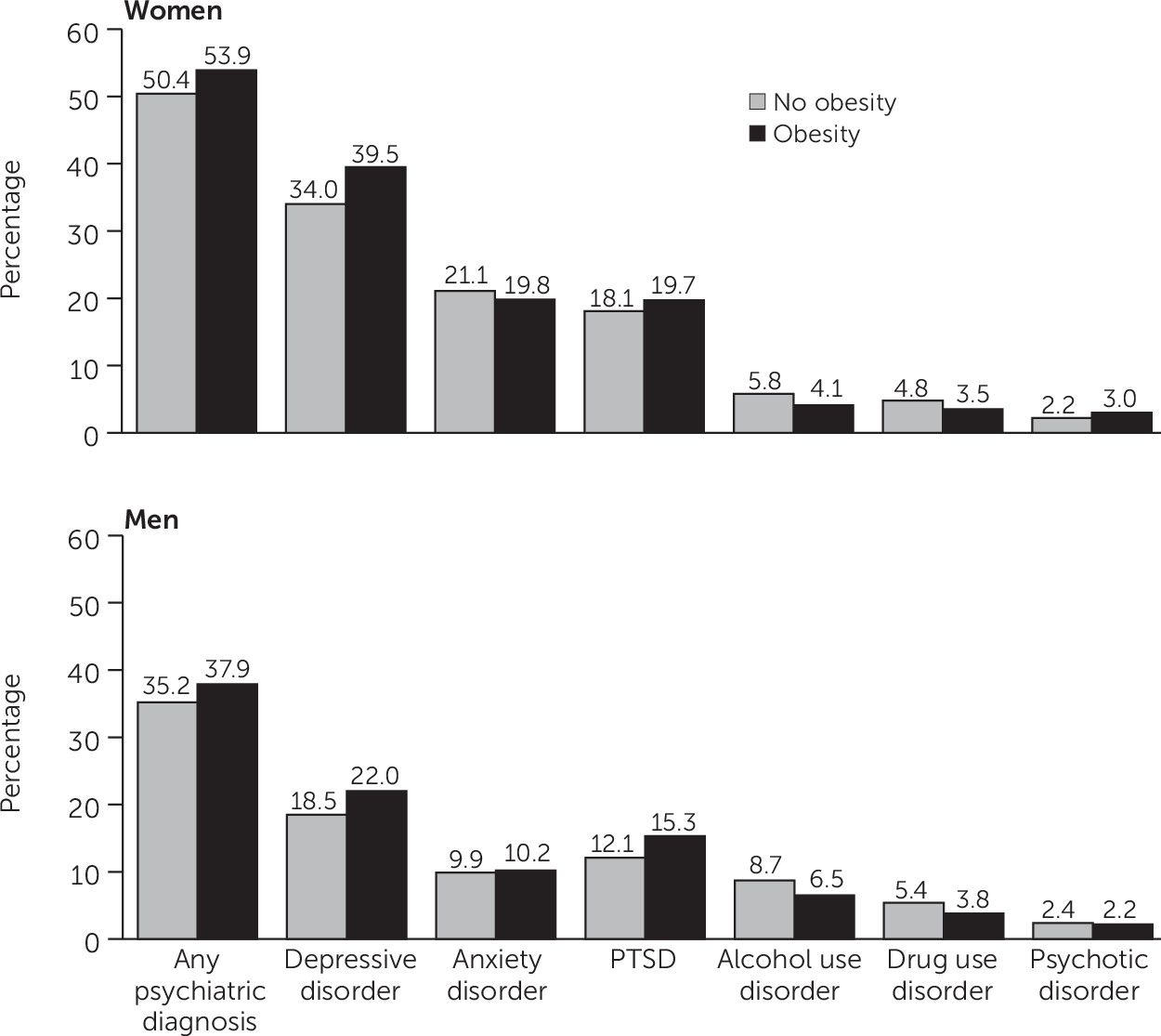

All chi-square tests assessing rates of psychiatric diagnoses (any and specific diagnoses) by obesity status (obesity vs. no obesity) were statistically significant (p<0.001 for all). As seen in

Figure 1, a greater proportion of women with obesity had any psychiatric diagnosis (53.9%), compared with women without obesity (50.4%). The same was found for men; 37.9% of men with obesity had any psychiatric diagnosis, compared with 35.2% without obesity.

As seen in

Figure 1, depressive disorders were the most common diagnoses among women with and without obesity. The difference in the rate of depressive disorder diagnoses among women with or without obesity was on the border of the clinically significant threshold (39.5% vs. 34.0%). It is notable that PTSD and psychotic disorder diagnosis rates were also higher among women with obesity, with a nearly 50% higher rate of psychotic disorders among women with obesity versus without obesity (3.0% vs. 2.2%). Substance use disorder diagnosis rates were lower among women with versus without obesity, with large relative differences. Anxiety disorder diagnosis rates were slightly lower among women with versus without obesity.

Among men, depression was the most commonly diagnosed condition, and men with obesity had higher rates than those without obesity (

Figure 1). There was a 25% higher PTSD diagnosis rate in men with obesity (15.3%) versus men without obesity (12.1%). Substance use disorder diagnosis rates were lower among men with obesity versus without obesity, and as was seen among women, the relative differences were sizable.

The online supplement provides psychiatric diagnosis rates within normal weight, overweight, and obesity classes. The same patterns were generally observed for these more granular weight categories.

Discussion

This national, population-based study is one of the first to provide information on psychiatric diagnoses rates among women and men with and without obesity. We found a higher rate of psychiatric diagnoses among people with obesity versus without obesity, particularly with regard to depression and PTSD. Women with obesity had higher rates of psychotic disorder diagnoses than women without obesity. In addition, women and men with obesity had lower rates of substance use disorder diagnoses than those without obesity. Women with obesity had slightly lower rates of anxiety disorder diagnoses than women without obesity. Although small, this finding has not been previously reported, perhaps because much of the previous work occurred before anxiety disorders and PTSD became separate diagnostic categories.

As in past work, rates of mental disorders were more common among women than among men (

5,

7). However, rates of psychiatric diagnoses were higher than in previous studies comparing the diagnosis rates of people with and without obesity (

5,

7). Because of differences between veterans who use VHA and the general population (

11), it is not possible to make direct comparisons. Nonetheless, the results underscore the substantial mental health challenges facing VHA patients with obesity. At the same time, it is important to recognize that a sizable proportion of women (46.1%) and men (62.2%) with obesity had no psychiatric diagnoses, particularly because most previous population-level studies have not provided these data.

Our results provide further support for the finding that many veterans have concurrent obesity and psychiatric diagnoses. Integrated treatment addressing obesity and mental health could benefit patients, providers, and the health care system by meeting patients’ physical and mental health needs in less time than separate treatment. Judiciously using resources to achieve this goal will require answering questions about optimal treatments for patients with different combinations of conditions. For example, given that physical activity could help patients manage both obesity and depression (

12), health care systems could focus on exercise-based weight management programs. Alternatively, weight management could be explicitly incorporated into psychiatric care, extending the reach of weight management programs beyond current arrangements. In the latter case, stabilizing psychiatric symptoms may take priority over weight management, but psychiatrists could be encouraged to consider factors such as weight-related side effects of psychopharmaceuticals. Psychological treatments could also indirectly affect weight-related behaviors, for example, by helping patients use cognitive-behavioral skills to reduce emotional distress, which could also reduce emotional eating.

Existing work has found comparable weight loss among VHA patients with and without serious mental illness who participate in MOVE!, VHA’s flagship weight loss program (

9). Programs tailored for patients with serious mental illness and obesity have been shown to increase physical activity within (

13) and outside VHA (

14), a particularly promising development given that physical activity could affect mental health and weight. Additional research on the effectiveness of weight management programs tailored for people with less serious mental health conditions would help shape health services and program implementation. The high rates of psychiatric diagnoses among women in our findings suggest that it may be important for future research to occur in women’s health clinics with colocated medical and mental health services (

15).

Limitations to this study included a focus on VHA patients, who may not be representative of all U.S. citizens or veterans who do not use VHA. We did not assess differences by race or ethnicity, and we included normal weight and overweight in a single category, potentially attenuating differences. However, rates of psychiatric diagnoses among these groups are provided in the online supplement. Finally, given a reliance on administrative data, it is possible that patients had undiagnosed mental health conditions. Strengths included the national and diverse cohort representative of the universe of VHA patients as well as the availability of measured BMI values for categorizing those with and without obesity.

Conclusions

Clinical practices and policies supporting programs that simultaneously address weight management and mental health have the potential to help address the substantial rates of psychiatric diagnoses observed among people with obesity. Such services may be particularly useful for women. The novel finding of lower rates of anxiety disorders among women with obesity versus without obesity merit additional research to confirm the finding and to explain possible causal mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jimmy Lee, M.S., John Radin, M.P.H., Fay Saechao, M.P.H., and Eric Berg, M.S., for technical assistance and Jazmin Reyes-Portillo, Ph.D., and Vivian Yeh, Ph.D., for their feedback.