Suicide remains a leading cause of death in the United States, and suicide rates have risen in nearly every state from 1999 to 2016 (

1). Experiencing suicidal thoughts and attempting suicide are also pervasive across the U.S. population. In 2016, 9.8 million adults (ages 18 and older) reported having serious thoughts of killing themselves, and 1.3 million adults reported attempting suicide during the past 12 months (

2).

Regarding this public health crisis, it is important to link people who are experiencing suicidal thoughts and behaviors to accessible and immediate resources. Since the second half of the 20th century, suicide hotlines have played an important role in U.S. suicide prevention efforts by de-escalating people in crisis and referring them to community-based resources (

3–

5). In 1999, the National Hopeline Network became the first national suicide hotline (

6). Subsequently, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline was launched in 2005 and is currently the largest suicide hotline in the United States (

7). Calls are redirected to local call centers, where volunteer crisis counselors provide crisis intervention and service referrals (

8). The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline received 12 million calls from 2005 to 2017 and expects to receive the same number of calls within the next 4 years (

7). This high call volume emphasizes the role of empirical research in understanding hotline users.

Research indicates that commonly mentioned problems by users of U.S.-based suicide hotlines include mental and general health problems, financial instability, relationship problems, and housing problems (

3,

9). These psychosocial issues correspond with the contributing factors identified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for suicide among individuals with and without psychiatric diagnoses (

10). Yet, studies have often included samples from select call centers and have not reported on whether the types of issues vary by the number of calls per user (

3,

9), even though repeated callers account for most hotline calls (

11). This method obscures potential differences and severity of caller issues by varying frequency of usage. Also, available research has not measured how the issues of repeat callers may change by conversation (

11–

13). Because repeat callers and callers who report suicidal ideation or related behaviors require great amounts of hotline resources (

7,

12), it is important to identify these callers’ issues as a first step to inform crisis counseling interventions (

13).

Hotlines utilize new technology in an effort to increase help seeking among people who wish to remain anonymous or want to use different modalities (

14,

15). Crisis Text Line is a text-based platform supporting a network of crisis support organizations in an effort to increase help seeking for distressed individuals. This free hotline can be accessed via text message, either by phone or Facebook messenger. Users send a text message to the help number and are then connected to a crisis counselor based at one of the network’s crisis centers. The service was originally based in the United States and has now broadened its reach to Canada and the United Kingdom.

The demographic characteristics of the hotline’s users are diverse. Approximately 75% of users are younger than age 25 (

16). Of the texters, 6% have identified as Native American, and 19% have identified as Latinx or Hispanic (

16)—two ethnic groups that have been traditionally less likely than white non-Latinx residents to seek help via phone hotlines (

17,

18). Additionally, 20% of the hotline’s user volume comes from the lowest 10% of income zip codes in the United States (

16).

Texters can decide to have their anonymous conversations scrubbed from the hotline’s database. Texter data may inform literature on hotline services and advise training and interventions conducted by crisis counselors. Because the hotline uses a machine-learning algorithm to help high-risk texters first (i.e., those who report suicidal ideation, previous suicide attempts, or both;

19), it is imperative that crisis counselors understand the needs and issues of these texters.

Considering the interest in technology-enhanced crisis hotlines (

8) and the use of text messages in suicide attempt prevention (

20), more peer-reviewed studies on large-scale conversations of text message hotlines are needed (

21–

23). Because research suggests that individuals who report suicidality are often repeated users of text-based hotlines (

22), in this study we aimed to increase knowledge by exploring distinct classes of texters who report suicidality by frequency of Crisis Text Line use and by whether the conversation was the first contact with the hotline, one of two contacts, or the last of several. Usage frequency highlights differences between individuals who have potentially acute versus ongoing issues, whereas conversation number among repeated texters allows insight into whether latent subgroups change by interaction with the hotline. Identifying subgroups of texters and their issues may inform text message hotline counselors on how to communicate with texters who report suicidality and alleviate crises (

11,

24,

25).

Methods

The original data set included 211,258 Crisis Text Line conversations in which users mentioned current or previous suicidality from 2013 to 2017. Data scientists determined suicidality through a word search of all conversations approved for research purposes during the hotline’s initial years of service. Data scientists queried the message-level data using machine-learning techniques to find all conversations that included associated terms and word combinations (i.e., phrases that expressed previous or current suicidality, such as “overdose”). The machine-learning model was programmed to predict suicide risk by reading variability in text messages and understanding context (

19). The model can identify 86% of people at severe imminent risk for suicide in their first conversations. Additional queries ensured that all selected conversations mentioned phrases related to suicide and that the hotline users and crisis counselors were engaged in actual conversations rather than in “dropped” or incomplete conversations.

Subsamples by Usage Frequency and Number of Conversations

All conversations were from the U.S.-based branch of the hotline. For this analysis, subsamples were created on the basis of the users’ frequency (i.e., total number of text conversations from the same phone number) of accessing the service and conversation number (for frequent texters). Cases with a third-party issue tag were removed from the sample (N=5,690) because this tag indicated that the hotline user was seeking advice for another person rather than for him- or herself; therefore, the suicidal person was not participating in the conversation. Each texter received a unique number after initial contact with the hotline, and the frequency of the texter identification number within the data set indicated whether a texter had called once, twice, or three or more times. One-time users included 92,304 participants, composing 44.9% of the full sample’s conversations (N=205,568). Two-time users (N=15,999) contributed 31,998 conversations (15.6%). Texters contacting the hotline three or more times (N=14,606) contributed 81,266 conversations (39.5%), but only the first and last conversations were included in this analysis to evaluate whether texter issues were different between the initial contact with the hotline and the final conversation. The final analytic sample comprised 153,514 conversations from 122,909 individuals.

This study was approved by the internal review boards from the respected universities as exempt from human subject research. The data set did not include any identifying information of the texters or crisis counselors (e.g., names or specific locations). Access to the aggregate-level texter data were granted by the hotline as part of its initial data enclave program (

26).

Measures

Indicators of psychosocial issues were related to four domains: psychological health, relational life, abuse, and environmental stressors. Crisis counselors “tagged” or reported psychosocial issues at the completion of each conversation on the basis of its content. Crisis counselors are volunteers who have completed 34 hours of supervised training and who have been vetted by the hotline to respond to and document calls. Crisis counselors selected from a list of 35 issue tags that had been established by the hotline. Seven tags were excluded from our analysis because they did not inform the latent construct of psychosocial issues, were redundant for our sample (i.e., suicidal ideation), and had been identified by the hotline’s research scientists as highly biased: suicidal ideation, third-party caller, medication issues, none, other, psychiatric hospitalization, and problems with therapist or psychiatrist.

Twenty-eight issues were selected to measure the psychosocial issue construct, including seven psychological health tags (depression, self-harm, anxiety, mental health issues, stress, eating disorders, substance use), seven relational tags (family, friends, relationships, bereavement, isolation, bullying, LGBTQ [lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning]), five abuse tags (physical, sexual, emotional, domestic violence, sexual assault), and nine environmental tags (medical, financial, work, educational testing, school, military, homelessness, homicide, and local and national elections). Tagging was based on the discretion of the crisis counselor. Demographic variables were excluded from the analysis because of the high amount of missing data (approximately 92%). Missing or incomplete caller or texter demographic data are not uncommon in hotline research (

11,

27,

28) given that hotlines are an anonymous crisis service. Yet, the amount of missing data in our study exceeded that of other studies (with values ranging from approximately 1% to 64%).

Analysis

The five subsamples based on frequency of use and conversation number were described according to the 28 issue tags informing the latent construct. To facilitate theoretical interpretation of the tags and our findings, we categorized tags into one of four broad issue domains: psychological, relational, abuse, and environmental. We then used latent class analysis (LCA;

29,

30) with an expectation-maximum algorithm to classify texters from subpopulations or “classes” with similar psychosocial issues during their first and last conversation by subsample of users grouped by frequency of use and conversation number. The categorization of issues by psychosocial tag did not influence modeling of the latent classes because all 28 issues were included in the analyses.

LCA is an appropriate statistical technique for our study because it identifies two or more unobserved subgroups of participants on the basis of covariation between multiple observed indicator variables (

31,

32). Class enumeration occurred within each frequency and conversation subsample, guided by fit indices and considerations of parsimony (

32). Within each subsample, we implemented one- to five-class LCA models and evaluated the following fit statistics: Akaike information criterion, Bayesian information criterion, sample size–adjusted Bayesian information criterion, and Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test (

33).

Starting with a one-class model (the baseline comparison for all subsequent models), enumeration continued until empirical underidentification or convergence problems signaled that the inclusion of additional classes was not needed or feasible (see

online supplement). Entropy was also estimated to evaluate quality of class separation (

34), with values approaching 1 indicating clearer distinction between classes on the basis of the indicators (

35). Following model selection, class-specific probabilities of having an item tagged were graphically displayed within each frequency and conversation subsample. Analyses were conducted with Mplus, version 8.1 (

36).

Results

Table 1 displays the prevalence of the 28 psychosocial issue tags for each subsample (one-time users, first and second conversation among two-time users, and first and last conversation among ≥3-time users) Across the overall sample, depression (41.9%) and family concerns (25.0%) were the two most frequent issues. Among the one-time users, depression (42.2%) and family concerns (26.5%) were also the two most frequent issues. Among the two-time users, 45.0% described depression as an issue in their first conversation versus 37.7% in the second conversation. Family concerns were again a frequent issue in their first (25.5%) and second (21.9%) conversations. Among users who contacted the Crisis Text Line three or more times, depression (47.7%) and self-harm (25.7%) were the most frequent issues in the first conversation; depression (35.5%) and family concerns (19.2%) were the most frequent issues in the second conversation.

Class enumeration results and fit statistics for the unconditional latent class models are presented in

Table 2. On the basis of statistical and substantive results, a three-class solution was chosen for each of the five subgroups. Entropy (range 0.73–0.82) indicated that the most probable class assignment was good (

34).

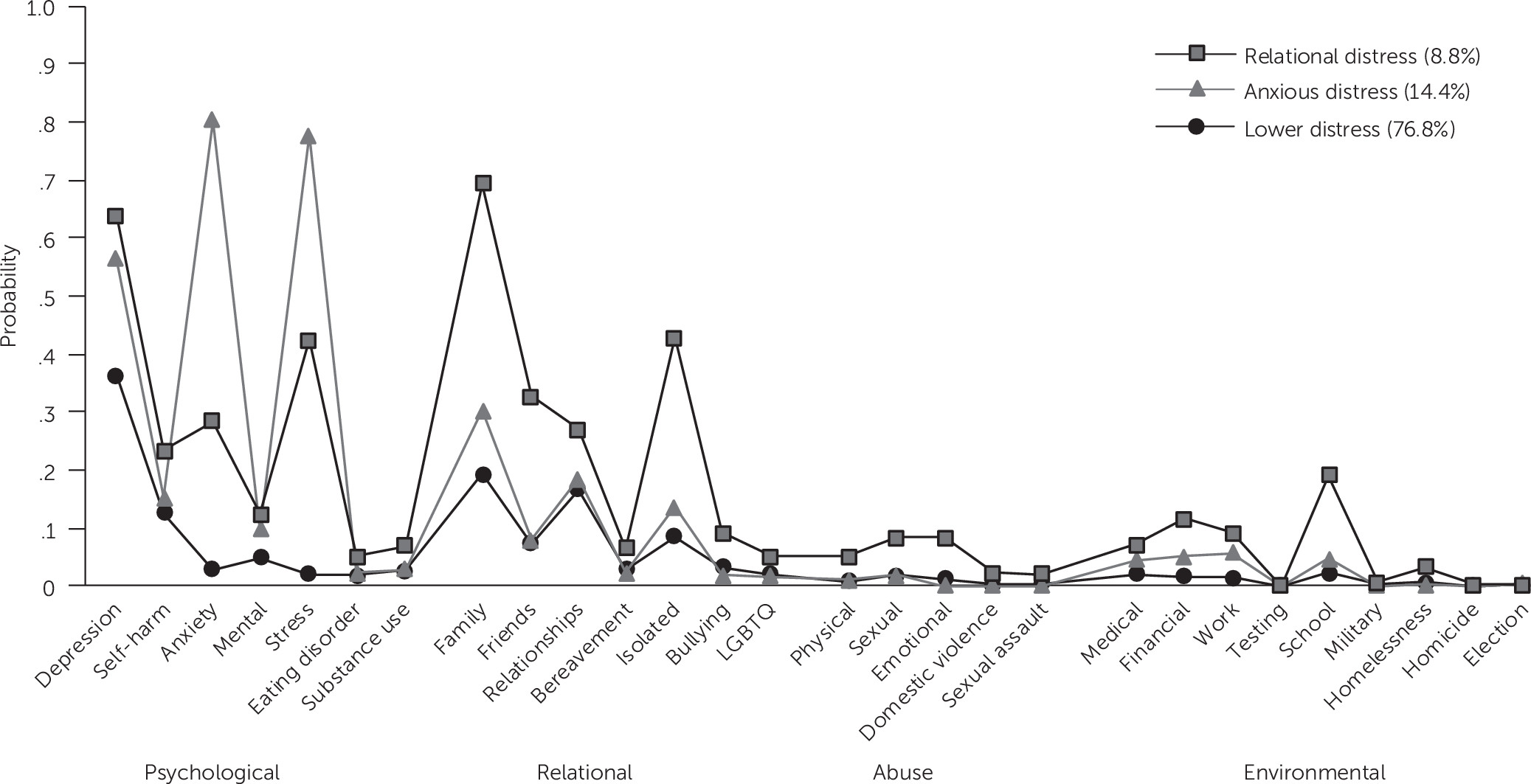

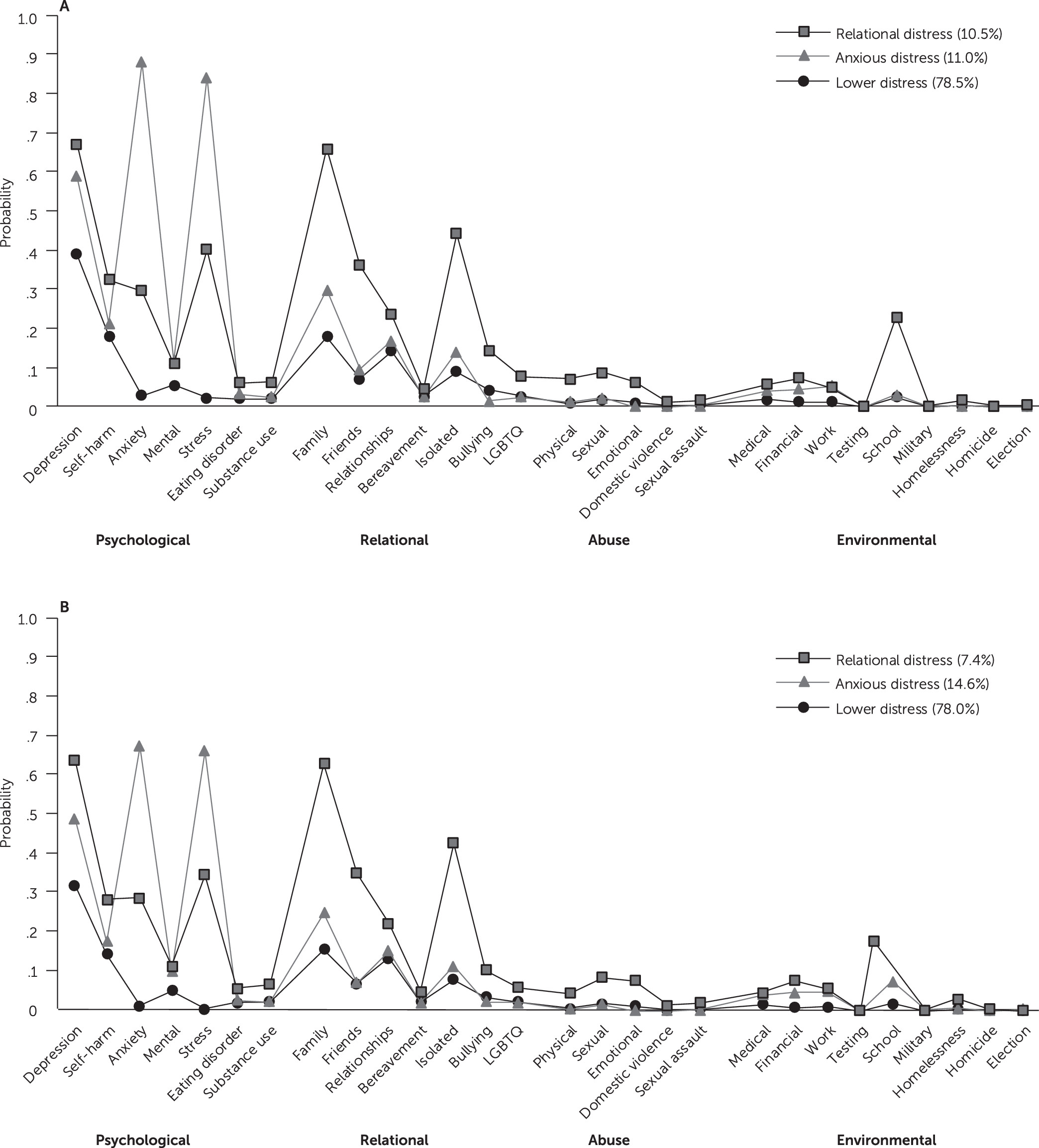

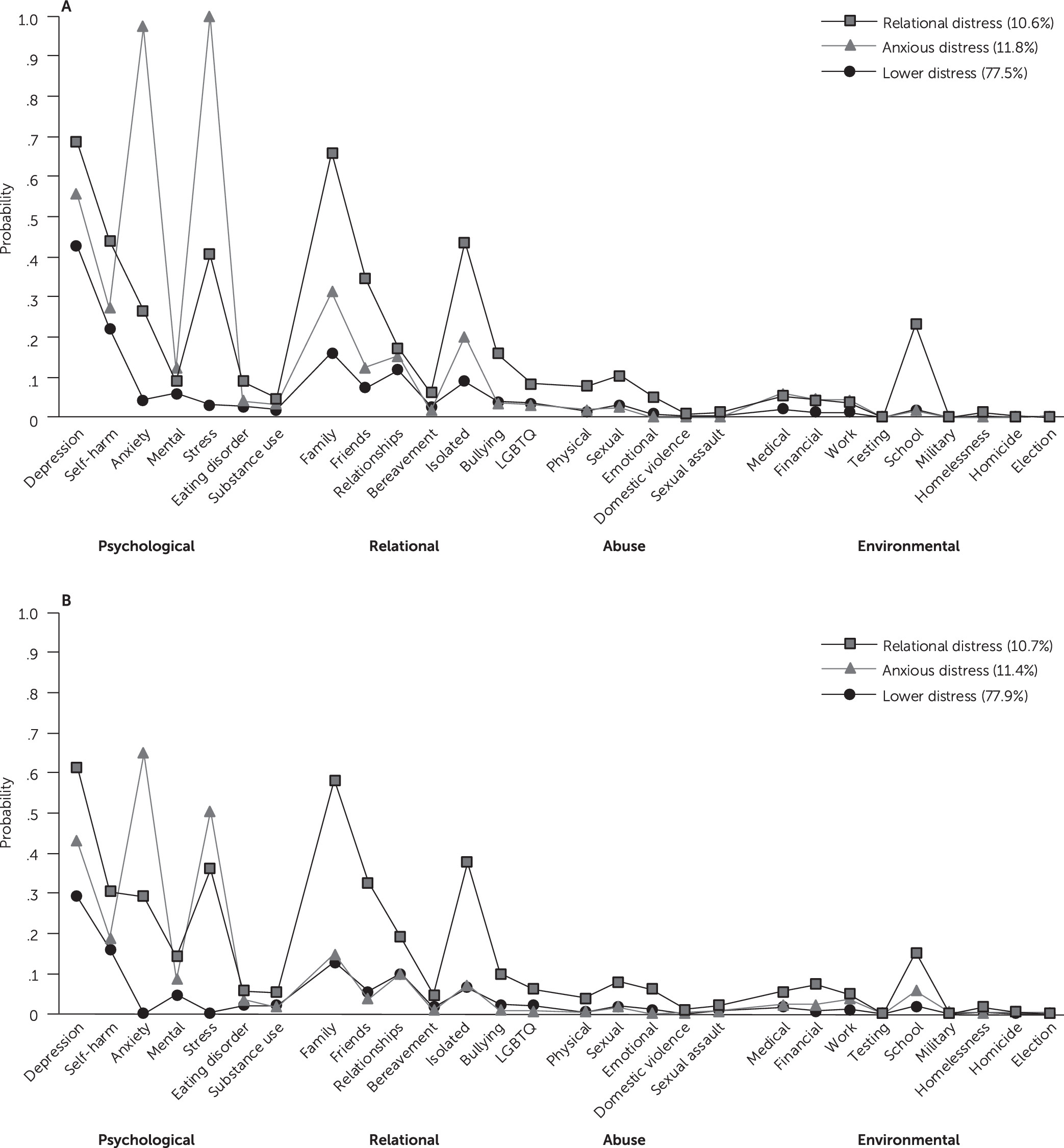

Similar classes of texters according to their psychosocial issue tags were found across all five frequency/conversation subgroups (

Figures 1,

2, and

3). The largest class (approximately 75% of each subsample) was named “lower distress” because the prevalence of all issues, regardless of domain, was lower in this class than in the other classes. However, theses texters expressed nonnegligible levels of depression and self-harm. Other salient issues among this class were relational in nature and pertained to family, friends, or relationships. The second largest class (11%–15% of each subsample) was composed of texters with “anxious distress,” named because they had the highest prevalence of anxiety or stress. They also were more likely to report depression than texters in the lower distress class.

Finally, the smallest group was the “relational distress” class (range 7%–11%). These texters were classified as having the highest prevalence of depression and self-harm. Although they had elevated levels of the majority of indicators in the relational domain, the most salient issues were related to family, friends, and isolation. In addition, school issues emerged as prominent concerns. These texters were classified as having medium levels of anxiety and stress compared with the other two classes. These three classes (lower distress, anxious distress, and relational distress) were found in all five subsamples.

Discussion

In this large-scale study, the authors explored distinct classes of users of the Crisis Text Line who reported suicidality. Classes were based on texters’ presenting psychosocial issues and were explored across frequency of hotline use and conversation number. We found three general classes of texters who reported suicidal ideation or behaviors, which did not change greatly by frequency of hotline use or conversation number. Classes were distinguished mostly by prevalence of psychological and relational issues, as opposed to abuse and environmental issues, reported by crisis counselors during text message interactions. Whereas the most common subgroup across hotline use and conversation displayed fewer issues of depression and self-harm, two smaller subgroups demonstrated problems with stress, anxiety, friends, and school in addition to higher levels of depression and self-harm. Our results suggest that, despite differing frequency of hotline usage, most texters who reported suicidality endorse similar issues, and these issues did not seem to vary by conversation. However, there seemed to be distinct subgroups of texters on the basis of their presenting issues, which can inform hotline strategies.

These findings support the emerging research on the psychosocial issues of users of text message–based hotlines who report suicidal ideation. Sindahl et al. (

22) reported that self-harm, bullying, and interpersonal problems were co-occurring issues for Danish texters who reported suicidal ideation. Mental health problems, issues with family or partners, and rumination were the most prominent co-occurring issues for users of the Dutch 113Online suicide prevention crisis chat service (

27). Among callers from eight local telephone hotlines in the United States, Gould et al. (

37) identified similar psychosocial issues, including exposure to interpersonal problems, mental health concerns, and difficulty meeting basic needs (e.g., shelter, food). More research is needed to better understand the subgroups of users of text message hotlines who report suicidality across frequency of use and conversations, and how they may compare with telephone hotline users.

Our findings have implications for crisis counselor training. The LCA results suggest that, in addition to depression, suicidal texters primarily struggle with stress and anxiety management and interpersonal relationships. Crisis counselors should be prepared to use emotion regulation techniques to support texters until they receive community-based services. Specifically, crisis counselors should understand evidence-based coping skills suited for people with urges to self-harm, anxiety, and interpersonal issues outside of abuse.

Crisis counselors may also tailor approaches to the three distinct classes of texters that were found in the overall sample of texters who reported suicidality. Understanding that these subgroups exist may help crisis counselors address issues not initially presented by the texter. For example, a crisis counselor who engages a texter expressing school-related issues may also want to use open-ended questions to inquire about other issues known to be prevalent in the “relational” class (i.e., the class with the highest probability of school issues, such as problems with family, friends, and feelings of isolation. Because the classes present similarly across frequency and conversation subsamples, how the crisis counselor approaches the individual is not necessarily informed by a texter’s history with the hotline. In contrast to studies on frequent users (

11–

13), our findings suggest that knowing whether a texter is a repeat caller versus a one-time caller does not enhance the crisis counselor’s ability to address the psychosocial issues at hand.

To validate the tagging of texters’ psychosocial issues, the hotline counselor may ask for texters to self-report their most pressing issues. The storage of message-level data may also provide future opportunities to examine the validity and reliability of issues tags from conversations and to improve the accuracy of issue tagging. Such information may illuminate why texters who report suicidal ideation and related behaviors and who are tagged with similar issues display different frequencies of hotline usage and how to encourage community-based help seeking.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting these findings. As described in the Methods section, data were collected during the hotline’s initial years of service, and there are significant missing data on texter demographic characteristics (i.e., age, gender, and ethnicity). Therefore, we cannot apply the findings to specific populations. Recently, the hotline has used strategies to reduce missing data regarding user demographic characteristics and user experience, such as imputing survey responses for nonrespondents.

Additionally, the crisis counselors tagged texter conversations from a list of prevalent psychosocial issues versus collecting texters’ self-reported problems. Tags were at the discretion of one crisis counselor per conversation, and interrater reliability could not be calculated. Research scientists regularly perform quality checks of the issue tags and have removed highly biased tags from the list (see the Methods section). As previously mentioned, the inclusion of message-level data in future studies is another strategy to further validate the issue tags labeled by the crisis counselors. Last, individuals who use the hotline are a self-selecting population who are seeking help. The findings do not speak to psychosocial issues that non-help-seeking suicidal individuals endure.

Typically, hotline studies are naturalistic studies and do not include a control sample because callers are affected by various life circumstances and may engage in various help-seeking activities (

38). Although we did not have access to a comparison sample, future studies may include a sample of texters without suicidality so that differences and similarities in presenting psychosocial issues of texters can be evaluated.

Conclusions

Text message hotlines are one strategy to reach diverse groups of people with suicidal ideation and related behaviors on a nationwide basis. Yet, there is a disparity in peer-reviewed research that explores the meaningful subgroups of texters reporting suicidality. Findings suggest that most texters who report suicidality struggle with psychological and relational issues. However, distinct subgroups of texters face a unique constellation of issues. Crisis counselors may benefit from additional training on emotion regulation and interpersonal problem solving as well as from understanding which issues tend to co-occur. This training will allow crisis counselors to inquire about additional but unexpressed issues. Findings also have implications for how the hotline may supplement collection of texter information through user identification of psychosocial issues and message-level data. This information may inform how the severity and types of issues differ among subgroups of texters with suicidality and inform future implementation of hotline services.