Individuals diagnosed as having schizophrenia have a life expectancy approximately 30 years shorter than the general population (

1,

2). In the United States, an estimated 114,000 new presentations of psychosis occur annually (

3). Roughly 75% of individuals with psychotic disorders experience their first-episode psychosis (FEP) before age 25 (

4). Treatment of FEP initiated within the critical period following initial onset may improve short- and long-term outcomes for schizophrenia spectrum disorders (

5,

6).

Because of successes found in early intervention FEP programs (

7), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration allocates 10% of the Community Mental Health Services State Block Grant toward the implementation of programs that address FEP. Using these appropriated state funds, Washington State Health Care Authority implemented in 2014 the New Journeys early intervention program for FEP. The model is based primarily on NAVIGATE (

7). Approximately 13 states within the United States have since developed early intervention programs based on the NAVIGATE model, but to our knowledge, published data on the outcomes of these programs have been limited.

The aim of this article is to provide an overview and preliminary outcomes of Washington State’s New Journeys network for FEP through an examination of the initial changes in psychiatric symptoms, quality of life, educational and vocational functioning, and substance use for clients during the first 12 months of treatment.

Methods

New Journeys Intervention Model

The New Journeys treatment model includes individualized medication management, family psychoeducation, individual resiliency training, and supported employment and education components of NAVIGATE (

8,

9). Individualized medication management focuses on a shared decision-making approach to reduce symptoms and prevent relapses while managing side effects. The goal of individual family psychoeducation is to teach families about psychosis and its treatment while reducing family stress through communication and problem-solving skills.

Individual resiliency training is an individually delivered psychotherapeutic intervention based on positive psychology, illness self-management, and cognitive-behavioral therapy. It focuses on helping clients achieve their personal goals and develop resiliency and skills to target ongoing challenges. Supported employment and education are evidence-based models that support clients in developing and achieving employment and education goals related to their career interests (

10). All components of the New Journeys intervention are delivered in person. On the basis of client and family needs, clinicians determine whether family psychoeducation, individual resiliency training, and supported education and employment are delivered on site, within the home, or in the community. Each site utilizes a team-based approach facilitated by weekly meetings to coordinate treatment planning and engagement for each client. To serve a maximum of 30 clients, each team consists of one psychiatrist or advanced registered nurse practitioner (0.2 full-time equivalent [FTE]) and bachelor’s- or master’s-level mental health professionals in the following roles: program director or family education specialist (1.0 FTE), individual resiliency training clinician (1.0 FTE), supported employment and education specialist (1.0 FTE), and case manager (0.5 FTE). A peer specialist role (0.5 FTE) was added to the New Journeys model after the initial implementation period.

Consistent with the elements of a learning health system, and to increase the efficiency of data collection from clients, the implementation and evaluation team along with program developers, clinicians, and administrators modified and developed an existing Web-based dashboard (Toolkit) that would provide both data infrastructure and support a clinical feedback system. Before the implementation of New Journeys, clinicians and administrators provided feedback on the usability and acceptability of the Toolkit prototype, which was used to improve the Toolkit prior to implementation. The Toolkit facilitates the implementation, training, and supervision of evidence-based treatments, and it is accessible by log-in only.

New Journeys Sites

Each year, Washington State distributes a request for information for FEP sites, using funds from the Community Mental Health Services State Block Grant, to all behavioral health organizations and managed care entities in the state. Interested community-based sites are required to apply in response to the request for information. Applications are assessed on population need, experience, community and clinical resources, agency capacity, and sustainability. Determinations are based on the best fit for providing services. Through this mechanism, New Journeys has been implemented sequentially across five counties throughout Washington State. The evaluation team had no direct contact with program clients. The Washington State Institutional Review Board determined that this program evaluation was not human subjects research.

Participants

Between October 15, 2015, and December 31, 2018, a total of 201 potential clients were referred to five clinical sites, of which 112 clients were eligible after screening. Program eligibility included clients ages 15–40; a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, schizophreniform disorder, brief psychotic disorder, or other specified psychotic disorder, as assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders, Clinician Version (SCID-5-CV;

11); and presence of psychotic symptoms for greater than 1 week and less than 2 years and less than 6 months of treatment with antipsychotic medications. In 2018, a diagnosis of delusional disorder was added to the primary diagnosis inclusion criteria. All insurance types are accepted, and clients who are uninsured are also eligible to receive services. Exclusion criteria included psychosis due to substance intoxication or withdrawal or known to be the result of a medical condition, and more than one episode of psychosis (i.e., a psychotic episode that was followed by full symptom remission and then relapse to another episode).

Training Procedures

During the first 2 years, New Journeys team members participated in yearly in-person training conducted by NAVIGATE treatment developers and the implementation team. Trainers conducted a 2-day workshop that included large group presentations on current and past treatment practices and breakout sessions on specialty roles (i.e., program director, family clinician, individual resiliency training clinician, supported employment and education specialist, and prescribers) and corresponding treatment components, which consisted of demonstrations and behavioral rehearsals. In addition to the NAVIGATE training, team members participated in a 2-day SCID-5-CV training course conducted by a certified SCID trainer. New Journeys team members also participated in a 1-day of training that provided an overview of the Toolkit, information on clinical and functional measures, and an interpretation of results conducted by two members of the evaluation team. Training involved role play, mock data entry, and didactics. To address the training needs of new staff because of turnover, program directors conduct orientations to New Journeys training. Subsequently, the implementation and evaluation team coordinates with program directors to schedule role-specific measurement and data input training.

Ongoing Supervision

Two separate universities hold contracts with the state to provide implementation and evaluation, respectively. In year 1, sites participated in biweekly (for the first 6 months) and monthly phone-based consultations conducted by the NAVIGATE treatment developers. The implementation and evaluation teams provided continuous technical assistance and data monitoring. New Journeys site directors participated in individual monthly calls focused on missing data, site performance reports, barriers to data collection, and staff turnover.

Assessments

The Toolkit provided the online data management support for all sites. The evaluation team selected reliable and valid measures that captured areas of assessment in previous literature, provided meaningful clinical cut-points, were brief, and were at no cost to New Journeys sites (

12,

13). The measures selected were a mixture of self-reported and clinician-rated instruments to reduce the burden associated with collecting data. Self-reported measures were completed during appointment times, either directly by the client or delivered by trained providers at the request of the client. Demographic information, psychiatric symptoms, information on real-world functioning, and medical history were collected at intake by site staff.

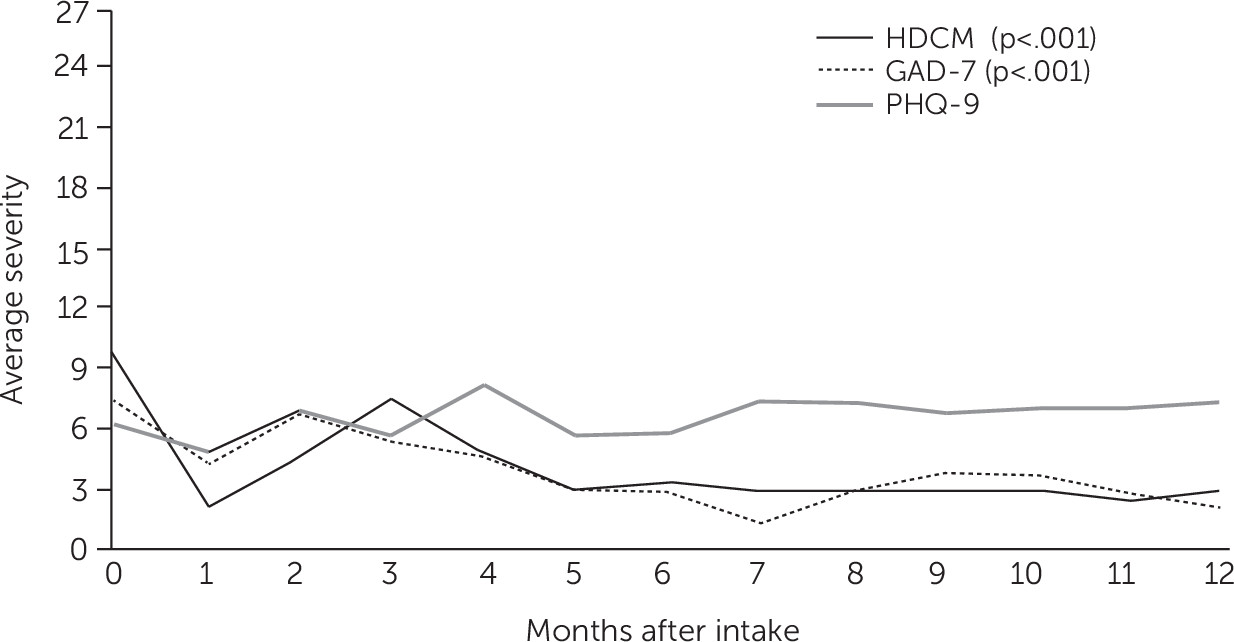

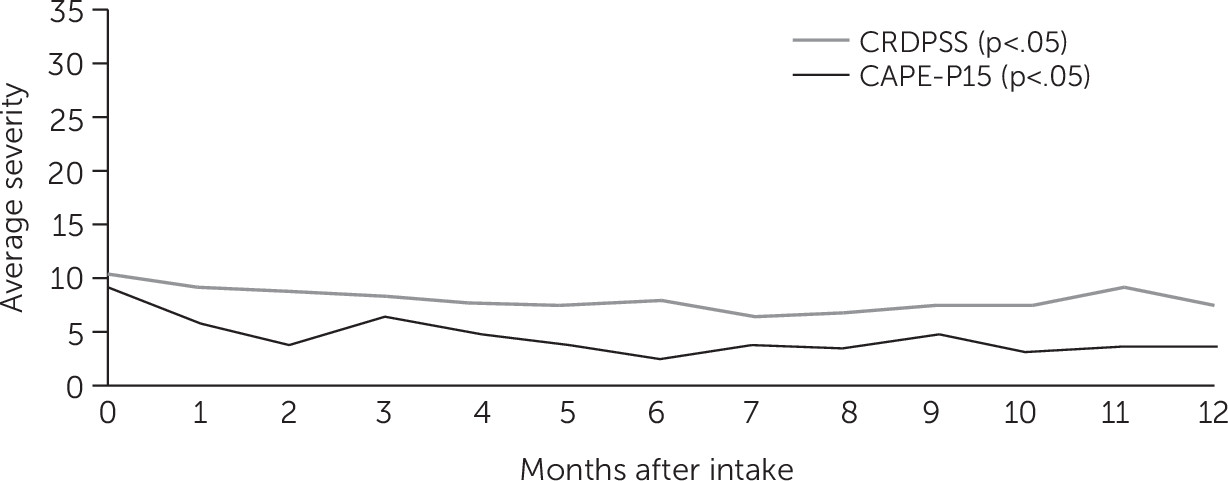

Psychiatric symptoms.

The eight-item

DSM-5 Clinician-Rated Dimensions of Psychosis Symptom Severity (CRDPSS) measure was administered separately to the client at intake and weekly during treatment by the individual resiliency training specialist to assess symptom severity across seven domains: hallucinations, delusions, disorganized speech, abnormal psychomotor behavior, negative symptoms, depression, and mania (

14,

15). The impaired cognition domain was omitted, which is consistent with the eligibility and exclusion criteria. The CRDPSS is rated on a 5-point Likert scale for each of the seven domains with a maximum score of 28, with higher scores indicative of more severe clinician-rated symptoms of psychosis (

16).

The 15-item Community Assessment of Psychic Experiences-Positive (CAPE-P15) scale is a self-report measure with a Cronbach’s α of 0.79 designed to assess the severity of psychosis-like experiences (

17). This measure was rated on a 4-point Likert scale with a maximum score of 45 in which higher scores represented more severe psychosis-like experiences (

18). The individual resiliency training specialist administered the CAPE-P15 at intake and monthly during treatment.

The nine-question Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) is a self-report measure with a Cronbach’s α of 0.89 and was administered by the prescriber monthly (

19). On a 4-point Likert scale, total scores range from 0 to 27, with higher scores representing more severe depression (

20).

The seven-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) self-report measure is rated on a 4-point Likert scale administered at intake and monthly during treatment with the prescriber and was used to assess symptoms of anxiety, with a Cronbach’s α between 0.79 and 0.91 (

21). Total scores range from 0 to 21, with higher scores representing more severe anxiety.

Quality of life.

Questions from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Health-Related Quality of Life, Healthy Days Core Module were administered at intake and monthly during treatment to evaluate perceptions of overall physical and mental health (

22–

24). For instance, clients were asked, “During the past 30 days, for about how many days did poor physical or mental health keep you from doing your usual activities, such as self-care, work, or recreation?” Responses with more days indicated poorer physical and mental well-being.

Educational status and vocational functioning.

Educational status was determined at intake and was reassessed monthly by the supported employment and education specialist on the basis of the client’s response to the question, “Are you currently enrolled in school?” Employment status was determined at intake and was reassessed monthly during treatment on the basis of the client’s response to the question, “Have you attended work or volunteered 20 or more hours per week in the last month?”

Substance use.

The Car-Relax-Alone-Forget-Family and Friends-Trouble (CRAFFT) measure was modified to include tobacco use and was administered at intake and reassessed monthly by the individual resiliency training specialist (

25). This six-item measure, with a Cronbach’s α between 0.68 and 0.86 (

26), was used to assess alcohol, drug, and tobacco use in the form of a yes or no question (e.g., “During the past 30 days, did you drink any alcohol [more than a few sips]?”). Affirmative response to two or more questions indicates risk.

Service utilization.

A service utilization measure assessing client attendance at individual components was obtained weekly by New Journeys staff.

Administrative Data

To examine differences in service utilization among New Journeys clients 24 months before and up to 24 months after intake, we obtained data using the Integrated Client Database, which contains individual-level administrative data from multiple state agencies on client service risks, history, and outcomes (

27). The 24-month window was selected to match the maximum timeframe of services clients could receive. Prescribed medications, emergency room (ER) visits, inpatient hospitalizations from three different facilities (i.e., medical hospitals, community psychiatric programs, state-funded psychiatric programs), and the use of behavioral health organization mental health services were assessed for only New Journeys participants with Medicaid claims and encounters. Administrative data were used to identify clients who had any services from Washington State’s Economic Services Administration, which includes Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, Basic Food, and other public assistance programs (e.g., Diversion Cash Assistance, Supplemental Security Income–State, Disability Lifeline Unemployment). Administrative data from different sources have varying lengths of delay, and clients admitted into the program after the latest data update were excluded from the analysis. As a result, the final sample sizes for these measures differ by data source.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses of demographic variables were conducted. Separate generalized estimating equations (GEEs) were used to assess all measures at baseline compared with the first 12 months of treatment. Twelve months was chosen as the cutoff point to maximize the number of available pairs used in GEE and to reduce the effect of missing data. For example, in measuring PHQ-9 scores, 83 clients (74%) were eligible for analysis when we used the 12-month window, which was consistent across measures. GEEs were also used to assess administrative data obtained from Medicaid-eligible participants 24 months preintake and up to 24 months postintake. Administrative data were retrieved for publicly insured eligible clients from four New Journeys sites (N=84). One site was omitted because of its brevity in the New Journeys network, and an additional seven clients were missing intake dates and were excluded from analyses. Given the various intake dates and lengths of treatment among clients, those who had an intake date after the reporting period for each agency were also excluded. Unstandardized regression coefficients and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are presented for continuous outcomes. Analyses were performed with SPSS, version 25.0, and statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Discussion

New Journeys serves as an example of a state-funded early intervention program for FEP within community-based mental health clinics, in which 54% (N=60) of clients were from racial-ethnic minority groups. More specifically, 34% (N=38) of clients identified as Hispanic, a disproportionately large number relative to the Hispanic population in Washington State (13%;

28). Despite the lack of control group, these preliminary findings demonstrate the potential impact of New Journeys on psychotic symptoms, psychosis-like experiences, and quality of life in the first 12 months of treatment. Together with the recently published outcomes from OnTrackNY (

29), these findings highlight the viability of the real-world implementation of an early intervention program and client outcomes during treatment in the United States.

Although previous studies have observed various rates of client enrollment in federal disability benefits (i.e., Supplemental Security Income, Social Security Disability Insurance;

29,

30), New Journeys assessed only receipt of state-funded public assistance. Clients significantly reduced the use of public assistance programs, which possibly demonstrates the impact of early intervention services on the receipt of state benefits. A plausible explanation for the decrease in public assistance may be due to a significant increase in school enrollment, which may affect eligibility for public assistance programs such as Basic Food. Rates of inpatient hospitalizations at medical facilities and state-funded psychiatric facilities were relatively low among clients, and no significant reductions were observed. However, from pre- to postintake, the utilization of community psychiatric inpatient hospitalizations decreased by 20% and ER visits decreased by approximately 40% among New Journeys clients. These findings were lower than the 60% decrease in hospitalizations reported after client enrollment in OnTrackNY (

29).

The disengagement rate observed in New Journeys (29.4%) was similar to the 30% rate of disengagement observed in a review of FEP programs (

31,

32). In an effort to reduce client and family disengagement, the state will incorporate additional engagement strategies and outreach activities into the New Journeys model, such as expanding the role of the peer support specialist to all sites. Substance use among New Journeys clients did not decrease in their first year of treatment. These findings are consistent with previous research, which found no significant changes in substance use in NAVIGATE (

33,

34). Previous research has found that substance use among those with FEP is negatively associated with treatment outcomes (

34–

36), further emphasizing the importance of incorporating effective substance use treatments into early intervention programs.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting these findings. First, these preliminary findings are limited by the absence of a control condition, making it difficult to draw inferences about the impact of the New Journeys model on client outcomes. Future efforts are aimed to identify a matched comparison using administrative data that will serve as a comparison group to determine the specific impact of New Journeys compared with standard care. Second, the fidelity of treatment delivery was not formally assessed because of evaluation constraints; thus, providers may or may not have delivered treatment components as intended, and the effect this had on treatment outcomes is unknown. However, informal fidelity review during monthly consultation calls was conducted. Third, there was ambiguity in the definition of completed or graduated for the nine clients who were reported as completed. Moving forward, treatment completion needs to be further defined and include clear thresholds for improvement in symptomology that is consistent across sites. Finally, the length of the program and the number of services utilized were not included in the model as potential treatment moderators. As clients continue to complete the New Journeys program, potential moderators such as these should be examined to determine whether the outcomes during and after treatment are sustained and to inform best practices among sites.

Conclusions

Enhancing early interventions for youths and young adults experiencing psychosis is a priority mission for Washington State. On the basis of the initial successes of New Journeys in addressing psychiatric symptoms and functional recovery, recent legislature has been passed promoting the rapid expansion of New Journeys in Washington State. As more community mental health clinics adopt early intervention programs for FEP, additional efforts focusing on substance use behaviors, general health, peer engagement, and measurement-based care are needed. The use of technology-based monitoring systems should also be leveraged to facilitate engagement during and after care. Continually evaluating the effectiveness of the New Journeys program in improving both clinical outcomes and quality of life for individuals with FEP will be crucial as the program continues to expand to new communities within Washington State.