Access to treatment for mental health services can enhance the initiation of appropriate treatment and preventative services, decrease financial strain, and minimize preventable hospitalizations (

1). Two thirds of primary care providers (PCPs) reported difficulty in accessing psychiatric care for their patients (

2). Furthermore, when a referral is sent to a mental health professional, only about half of these appointments are attended (

3). When access to care is delayed, patient satisfaction can be reduced, and health outcomes are poorer (

4). Currently, there is a shortage of psychiatric providers able to manage those in need of psychiatric care (

5). One emerging solution to this challenge is to leverage psychiatric expertise through evidence-based integration of mental health services into primary care settings, such as the psychiatric collaborative care model (CoCM) (

6).

The purpose of this column was to describe the transformation of psychiatric services at a midwestern federally qualified health center (FQHC) by implementing integrated care strategies and the CoCM over a 3-year period. The main outcome measured for this quality improvement (QI) project was the number of patients on the waitlist for a psychiatric referral. This report may be valuable in informing current practices striving to achieve similar objectives.

Setting, Process, Interventions, and Resources

The project was based in a midwestern FQHC comprising a large main campus medical home and seven satellite clinics. Health center staff included 19 M.D.s, 32 midlevel practitioners, and 12 behavioral health therapists. The therapists performed integrated care interventions consisting of single-visit warm handoffs directly after PCP appointments to address behavioral health concerns. Common encounters included assistance in diagnostic assessment, crisis management, psychoeducation, and brief interventions such as teaching relaxation in 20- to 30-minute sessions. The FQHC saw 41,868 patients in 2017. The patient population included 91% of individuals who lived more than 200% below the poverty line; 75% who were members of racial-ethnic minority groups, primarily Latinos; and 49% uninsured individuals (

7).

The FQHC had previously received funding for various mental health initiatives; before initiation of this work, an 8-hour-a-week psychiatric position was vacant for 9 months. Outside organizations providing psychiatric medication management were difficult to access because of extensive waiting lists, noncentralized referral sources, and staffing shortages. PCPs at the clinic had become the sole psychiatric medication providers for the majority of their patients, including those with severe and persistent mental illness. Referrals were made to psychiatric care for a full range of mental health diagnoses.

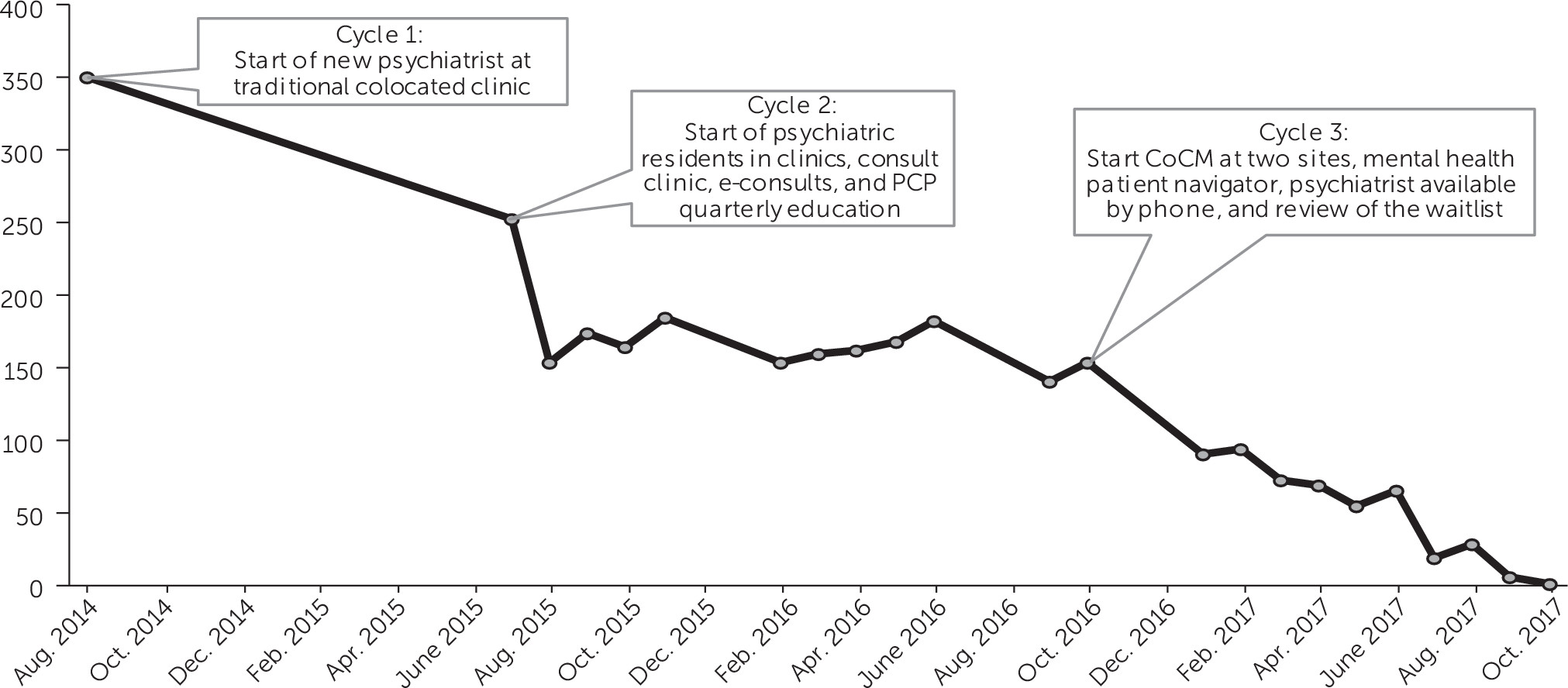

In August 2014, the waitlist to see a psychiatric provider at the FQHC consisted of 350 patients. At this time, the clinic began focusing on QI for access to psychiatric services and contracted with a local academic facility to provide 8 hours of psychiatric care per week. A team consisting of the chair of psychiatry; the chief medical officer of the FQHC; the behavioral health director of the FQHC; the contracted faculty psychiatrist working at the site; and, later, the residency program director met two to four times a year.

The transformation of this FQHC comprised three PDSA (plan-do-study-act) cycles, each 11–13 months in length. The academic facility identified this as an opportunity to develop a training site for psychiatric resident physicians to treat underserved individuals and gain experience in the primary care setting. The FQHC recognized this as an opportunity to establish a relationship with an academic facility and alleviate the problem of access to psychiatric services. The main outcome measure tracked for this QI project was the number of patients on the waitlist for a psychiatric referral. New referrals were accepted in an ongoing manner.

The first cycle lasted from August 2014 to June 2015, with the identified goals of reducing the waitlist and increasing patient satisfaction. The intervention was hiring a new psychiatrist for 8 hours a week to perform colocated care (shared space and medical records). The waitlist decreased from 350 to 252. The team concluded that the waitlists remained too long and would never be eliminated with the current practice. Through the iterative process, the team discussed altering the role of the clinician to be more consultative in nature, and the academic center secured funding to train residents at this site.

The second PDSA cycle lasted from July 2015 to September 2016. The identified goals were to provide a meaningful educational experience for the trainees, equip PCPs with skills to treat mental illness, and leverage psychiatric expertise to address the population in need. Interventions included placing one to two senior psychiatry residents in clinics for 8 hours a week, transitioning from traditional patient care to a one-time consultation clinic, utilization of e-consults, and providing PCP quarterly education (see online supplement). The waitlist decreased from 252 to 154. During evaluations, senior residents expressed that the rotation did not teach them anything new, given that it was so close to traditional care. An attempt was made to increase collaboration by setting up a phone call with the provider and a resident before the consultation. This was burdensome in the scheduling of PCP time and did not improve the resident experience. This intervention was abandoned. The chair of psychiatry suggested the use of the collaborative care model (CoCM) for the next cycle. The team set up a plan for the psychiatrist to train in this model, and the site explored the feasibility and resources needed for implementation.

The third and final PDSA cycle lasted from October 2016 to October 2017. The three goals were to maintain a commitment to previous goals, provide outcome-based treatment, and improve the resident experience by teaching unique collaborative care skills. The first intervention was the implementation of CoCM at two of the eight community clinical sites. Other integrated consultative strategies beyond the CoCM were simultaneously utilized to meet individual patient needs and decrease wait time. These interventions included hiring a mental health patient navigator, making the psychiatric consultant available by cell phone, and reviewing the waitlist (see

online supplement). The outcome of these interventions was that the number of patients on the waitlist decreased from 154 to 1. After year 3, the traditional psychiatric referral waitlist consisted of one patient, and there was a 1- to 2-week wait time for patients to enroll in the CoCM program.

Figure 1 illustrates a steady decrease in the number of patients on the waitlist. The CoCM outcome measures tracked for patients in the program included the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (every 2 weeks), the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale–7 (every 2 weeks), the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (monthly), and

DSM-5 cross-cutting measures (monthly). Direct psychiatric consultations were still available to providers for a full range of diagnoses. After the interventions, psychiatric consultations were utilized primarily by sites that did not have CoCM and for individuals with severe and persistent mental illness. The interventions were considered successful, and all were continued. Because of the success in clinical improvement and access to care, a plan to expand CoCM to all the clinical sites began.

Several resources were utilized to make this project possible. Organizational leadership involvement promoted cultural change. The chief medical officer was a QI team member and the physician champion. The academic affiliation helped in creating new ideas in the planning stage. Training and technical assistance for CoCM were accessed through the resources available from the American Psychiatric Association Support and Alignment Network (APA SAN), as part of the Transforming Clinical Practices Initiative (see online supplement). The psychiatric consultant completed core training in May 2016 at the APA annual meeting and participated in the APA SAN Collaborative Care Learning Collaborative in the spring of 2017. Resident physicians completed APA SAN training through online modules. The leadership accessed information on implementation, and information technology support used a registry template from the University of Washington AIMS Center Web site. The behavioral health care manager (BHCM) was a licensed independent mental health practitioner. The BHCM was trained in CoCM available through online modules on the University of Washington AIMS Center Web site, augmented with teaching from the psychiatric provider (see online supplement).

The FQHC received funding for mental health services through a Health Resources & Services Administration grant, which was not time limited. The behavioral health referral navigator and resident physician salaries were funded by a grant from the state. Billing of services provided shifted from the psychiatric consultant to the PCP and therapist. The behavior health care manager involved in CoCM billed for therapy time, and PCPs billed for their clinical visits. To promote sustainability, the site applied for and was granted payment for clinical visits by PCPs for medication management for the uninsured patients from the state’s regional behavioral health authorities. Before this, funding for medication management had gone only to psychiatric providers.

This study was approved by the Creighton University Institutional Research Board and determined to be exempt based on exemption category 4. The data did not have any patient identifiers, and informed consent was not needed.

Summary, Discussion, and Implications

The waitlist decreased during each QI cycle until there was only a 1- to 2-week wait time for access to services. Qualitative feedback included the following: the BHCM enjoyed the collaborative role, residents felt the CoCM model staffing time was their favorite part of the rotation, and PCPs felt supported in treating a variety of mental disorders.

Key strategies used in this effort included the CoCM, a transition from traditional care to a one-time consultation clinic, e-consults, quarterly PCP education in psychiatry, availability of a mental health patient navigator, a psychiatric consultant available by cell phone, and regular review of the waitlist (see the online supplement). We believe that these interventions were needed for improved access because, in traditional psychiatric care, a waitlist will stagnate because of the need for follow-up care limiting the opportunity for new evaluations. The CoCM used 2–3 hours of weekly psychiatric time to care for about 60–80 patients who would have otherwise been referred to traditional psychiatric care. The availability of psychiatric consultation through the CoCM, e-consult, and curbside consultation by telephone allowed many patients to be managed solely by indirect care. Reviewing waitlists identified patients who could be managed through indirect care. Last, with targeted PCP education, the PCP becomes less reliant on psychiatric consultation.