Child psychiatric hospitalizations are common and costly. Over the past 15 years, pediatric hospitalizations for mental disorders have increased by over 50%, with total expenditures of $11.6 billion (

1). Between 2005 and 2014, pediatric hospitalizations in U.S. children’s hospitals rose five times more among children with a psychiatric diagnosis than among children without a psychiatric diagnosis (

2). Recent studies suggest that one in four youths is readmitted to a psychiatric hospital within 1 year of discharge (

3–

6), with most readmissions occurring within 3 months (

7). Repeat hospitalizations disrupt social support and school performance and result in greater stigmatization for youths and their families (

8,

9). A national indicator of risk of poor quality of care is the rate of repeat hospitalizations within 7 and 30 days (

10). Nevertheless, questions have been raised as to whether repeated child psychiatric hospitalizations reflect hospital-level factors, ecological factors, or the complexity of the clinical presentation of the child served and the psychosocial factors involved (

11,

12).

Sociodemographic characteristics appear to influence the risk of readmission, although findings are mixed (

13,

14). For example, studies suggest that younger children (

4,

13,

15) as well as older children (

14,

16) may be more frequently readmitted, whereas other studies find no relationship with age (

17,

18). Similarly, the posited relationships between readmission and gender (

13,

16,

19), race-ethnicity (

7,

13,

20), guardianship status (

6,

16,

19,

21), early life stress and child abuse (

6), and socioeconomic status (

16,

22) are multidirectional. The role of disease severity also remains unclear, with variable findings regarding primary diagnosis and symptom severity (

23), comorbidity (

3), self-injury, and suicidality (

5,

6,

23,

24).

Characteristics of hospitalization may also predict readmission, such as length of stay (

6,

14) (LOS), access to inpatient case management services (

23), and postdischarge care, including aftercare services (

17), disposition to residential treatment or partial hospitalization (

23), and discharge medications (

21,

22,

25). Identifying predictors of readmission at this level can inform health policies and quality improvement interventions to mitigate cost and burden to systems and families (

26). However, to our knowledge, no quantitative meta-analysis of the literature on child psychiatric hospital readmissions has been conducted.

Methods

Search Strategy

A systematic search was performed in PubMed/MEDLINE, Google Scholar, and PsycINFO databases from January 1, 1997, through June 1, 2018. The study timeline was restricted to these years in light of substantial changes to systems of practice in hospitals, including the advent of managed care, so as to ensure relevance of our results to current providers. Search terms included (psych* OR mental health OR schizophreni* OR schizoaffective OR psychosis OR psychotic OR bipolar OR manic OR mania OR depress* OR mood OR autism OR attention deficit hyperactivity disorders OR neurodevelopmental) AND (readmi* OR rehosp* OR utilization OR hospital* OR admi*) AND (adolesc* OR child* OR youth). (Search strings are detailed in a table in an online supplement to this article.) The search strategy was augmented via review of the reference lists of each of the included manuscripts, citation tracking, and, when necessary, contact with study authors.

Study Selection

The study adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement guidelines (

28) and followed a predefined protocol registered in PROSPERO (

29) (CRD42018117268). Original studies published in peer-reviewed English-language journals were reviewed. The following inclusion criteria were applied. First, study participants were restricted to children and adolescents (age <18). Studies including adults (≥18 years old) were included only if the study reported data separately for youths. Second, eligible studies had to include a group of youths admitted to a psychiatric inpatient treatment setting (thus studies involving admission to day treatment programs and group homes were excluded). Studies solely targeting emergency psychiatric evaluation services were excluded if no data on hospitalization were available. Exclusion criteria were as follows: publications not including quantitative measures, such as reviews or book chapters; studies not published in English; studies that included adult participants without reporting separate data for youths; studies solely assessing eating disorders and chemical dependency units (because of substantial differences in LOS, medical acuity, and pathology); and studies that did not assess at least one potential predictor of psychiatric readmission.

Data Extraction

The effect size (ES), or statistic from which an ES could be calculated, was extracted for each predictor of readmission. In addition we extracted the following data when available: study author(s), study year, sample size, mean age of participants, sex or gender, and race-ethnicity of participants, study location, study design, institutional study site, level of care, study-specific exclusion criteria (including medical acuity and presence of an autism spectrum disorder [ASD] or intellectual disability [ID] diagnosis), most prevalent diagnoses of the study population, whether the study specifically targeted suicidal youths (attempt or ideation), percentage of suicidal youths, percentage of youths in foster care, provision and type of aftercare services (follow-up appointments, wraparound services, and case management), mean LOS (days), mean time to readmission (months), and study duration (days).

The literature search, title and abstract screening, decision to include full-text articles, and data extraction were independently reviewed by two authors (J.E. and B.Z.). Disagreements were resolved via consensus ratings. In the absence of consensus, a third author (M.S. or B.L.) was consulted.

Risk of Bias

Assessment of the quality of included studies was conducted with an eight-item form adapted from previously published quality criteria for systematic reviews (

30,

31). The items assessed whether the study had a nationally representative sample, used a representative sampling time frame, and used random selection. The items also assessed the quality of data collection, use of a sufficient timeline over which to assess readmissions, use of an appropriate sampling size, and presence of multivariate analyses. The last item was an overall assessment of the risk of bias of the study.

Bias was ascertained independently by two authors (J.E. and B.Z.). Each item was rated as low, moderate, or high risk of bias. When studies were missing information, the item was scored as high risk of bias. Thus the overall measurement tended to overestimate risk of bias. Disagreements between raters were resolved via discussion.

Statistical Analyses

Studies were combined if at least three independent studies reported an ES for a given predictor. Because studies reported both continuous and dichotomous measures, ES estimates were converted to the natural logarithmic transformation of odds ratios (ORs). This was done because conversion to a dichotomous ES is more conservative and less prone to biases than conversion from a dichotomous to a continuous ES (

32). Effects were pooled by using the DerSimonian-Laird random-effects method of meta-analysis to account for variation between studies and to allow for generalization beyond the study population (

33,

34). Following pooling, the log ORs were converted to ORs for ease of interpretation. Because survival data cannot be readily statistically combined with dichotomous cross-sectional data, survival analyses were tracked and reported separately. Each predictor was assessed for publication bias by using Egger’s test (

35,

36). Funnel plots were inspected for asymmetry.

Heterogeneity was measured via the I

2 statistic and Cochran’s Q test (

33,

35). Potential sources of heterogeneity were explored by using subgroup meta-analyses (categorical covariates) or random-effects meta-regression (continuous covariates). Meta-regression is a well-established methodology in meta-analysis in which an outcome variable (the effect estimate) is predicted according to the values of one or more explanatory variables (characteristics of studies that might influence the size of the effect estimate) (

37). Subgroup analyses were performed if at least five studies evaluated the same predictor. The following variables were considered in subgroup analyses: study location (U.S. versus international); study design (retrospective versus prospective); study site (single versus multisite); inclusion versus exclusion of individuals with ASD or ID, mood disorders, or suicidality; and inclusion versus exclusion of previously hospitalized children. The following variables were considered in univariate meta-regression: sample size, study year, mean age, gender (percentage female), race-ethnicity (percentage Caucasian because insufficient data were available for other races and ethnicities), mean LOS, mean days to readmission, follow-up interval, and percentage of sample hospitalized for suicidality.

All analyses were performed with the metan package of Stata MP software, version 15.1 (

38,

39). Meta-regressions were performed via the metareg command. An alpha level of 0.05 conferred statistical significance, and p values were two-tailed. The study did not meet criteria for review by an institutional review board.

Discussion

For pediatric mental health admissions, indicators of clinical severity emerged as predictive of repeat hospitalization. Measures of clinical severity at the patient and hospital levels were more predictive of readmission than were sociodemographic characteristics. Studies were heterogeneous with regard to methodology and practice setting, and analyses of bias suggested a need for larger controlled studies and standardization of methodology.

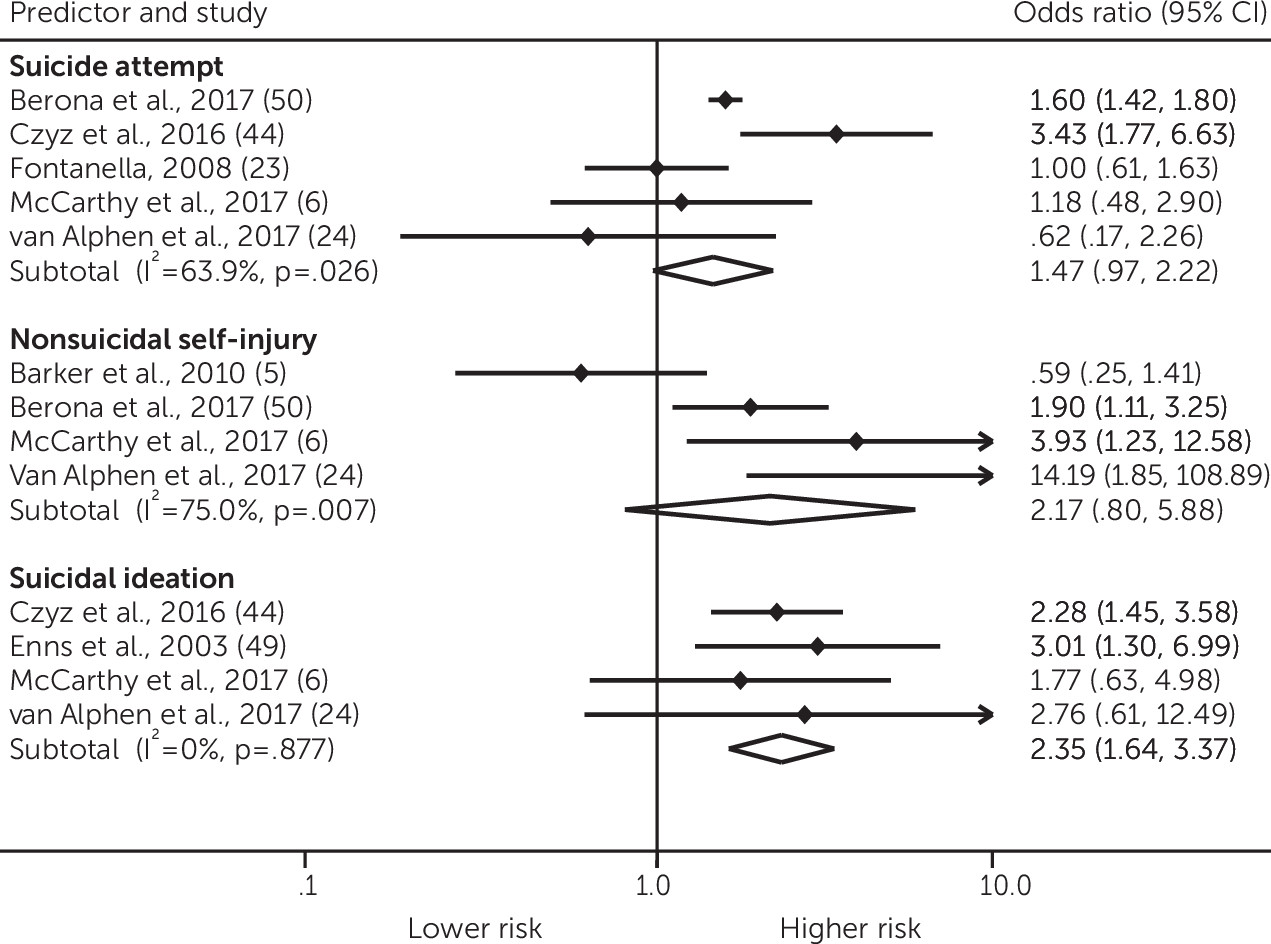

In multiple cases, demographic features significantly moderated the size of the relationship between predictors and readmission. For example, although gender was not a significant predictor of readmission itself, studies with more females tended to find a positive relationship between history of suicide attempt and readmission, whereas studies with more males tended to find a positive relationship between history of nonsuicidal self-injury and readmission. This may suggest that controlling for gender is important in identifying predictors of readmission. Moreover, screening for nonsuicidal self-injury, particularly among males, for whom self-injury is less common (

53), may help identify children at elevated risk of readmission. The wide breadth of acute mental health care settings of the included studies may have contributed to the nonsignificance of demographic features (age, gender, and race-ethnicity) in directly predicting readmission when ESs were pooled. Of note, no studies reported data for gender nonbinary youths.

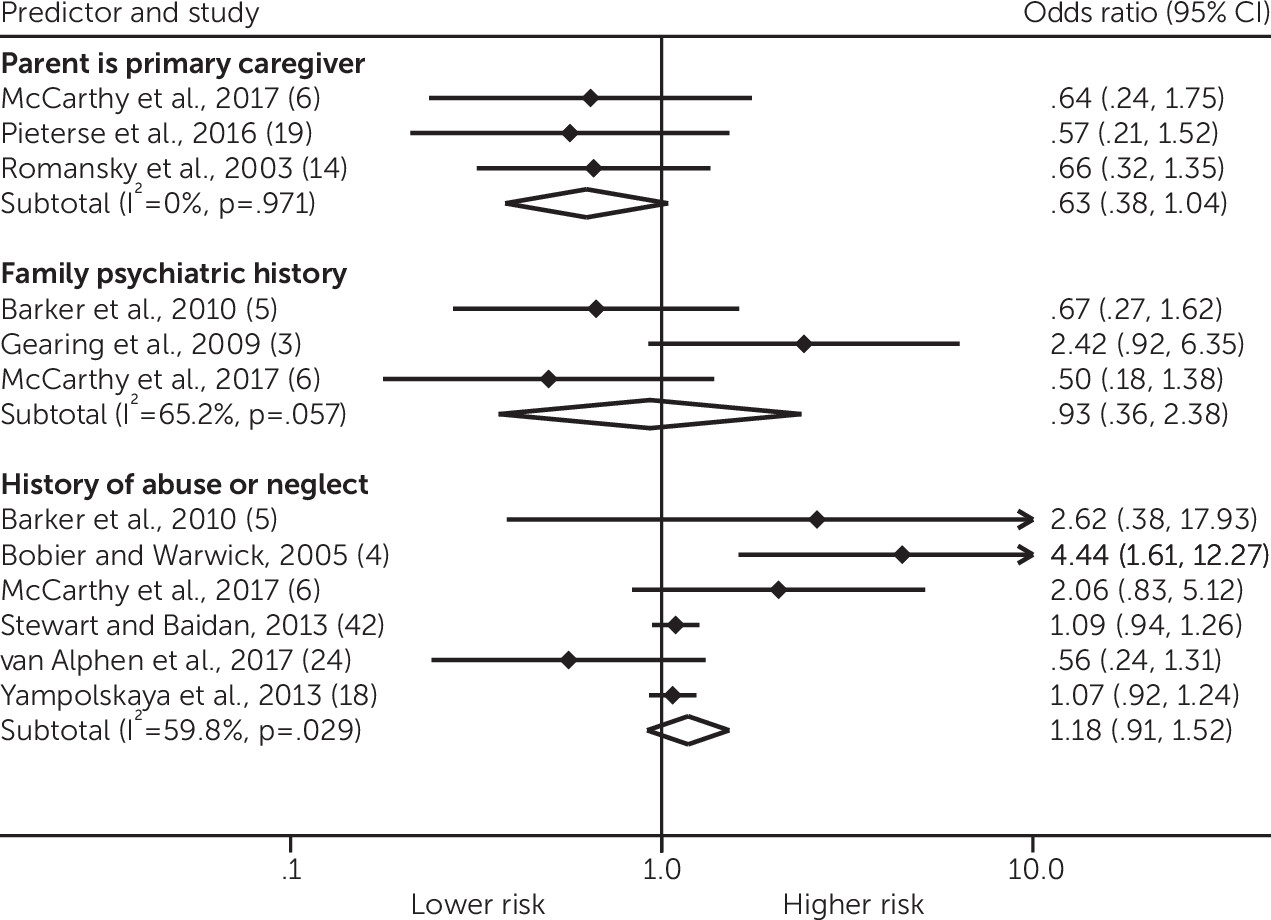

This meta-analysis identified 20 different measures of family functioning (e.g., family risk index, parent-child conflict, and parental involvement). However, only three of these measures (primary caretaker, family psychiatric history, and history of abuse or neglect) were reported by more than one study, and none reached significance when pooled. There was a trend toward significance that youths whose primary caregiver was a parent were at lower risk of readmission. Future standardization of measures pertaining to family and peer factors would be beneficial, because homegrown measures are difficult to combine or compare.

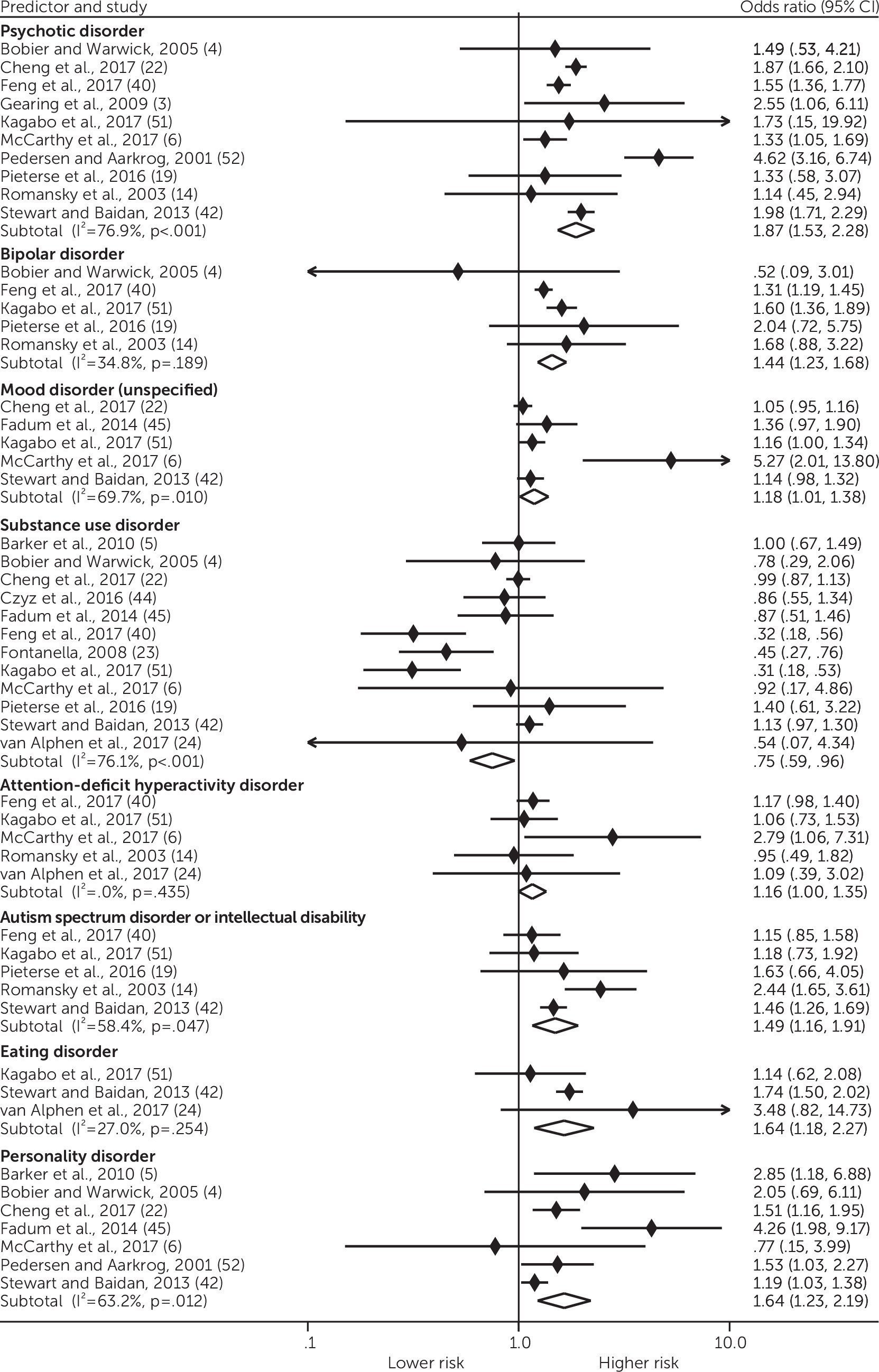

Across all predictors, youths with suicidality and more severe illness experienced an elevated risk of readmission. Youths with suicidal ideation were readmitted at twice the frequency of youths without suicidal ideation. Suicidality is a known predictor of psychiatric readmission among adults (

54), and as psychiatric inpatient units are increasingly transformed into short-term crisis intervention facilities, rates of admission associated with suicidality have increased (

55). Because criteria for admission frequently revolve around suicidality, impulsivity, and situational aggression, admissions for suicidality may be an indirect reflection of readmission risk as perceived by the provider. Serious mental illness (psychotic and mood disorders) was associated with increased risk of readmission in this analysis. It is striking that the relationship between psychotic disorders and readmission persisted even with the wide variation in number of study sites, study design, mean LOS and duration of follow-up, and study location.

Unexpectedly, substance use disorders were associated with a reduced risk of readmission. This finding may suggest that youths with substance use disorders are referred to substance use treatment, experience poorer access to care, or are diverted from psychiatric readmission—for example, through incarceration in juvenile detention facilities. Alternatively, youths with substance use disorders may have a higher probability of loss to follow-up because of transition between systems of care, with relatively few studies tracking readmissions across institutions. Beyond substance use disorders, readmission estimates for populations that may require specialty mental health services, such as youths with eating disorders, may be more difficult to interpret because of movement between primary and specialty mental health care.

ASD and ID were associated with increased risk of readmission. Insufficient data were reported to distinguish rates of readmission between youths with ASD or ID and ASD alone. Of the five available studies investigating this population, none were prospective, none reported data for the racial-ethnic composition of the study population, none reported mean time to readmission, and only three included youths ever previously hospitalized. The aggregated national costs of supporting children with ASD in the United States is $61 billion per year (

56). Research has suggested that increased spending on respite care is linearly associated in adjusted analyses with decreased odds of hospitalization (

57). The results of this meta-analysis suggest that the availability of robust aftercare services and respite care may be beneficial for this population in mitigating frequent readmissions; however, overall, more data are needed regarding risk of readmission in ASD and ID populations, which will, in turn, inform interventions to reduce acute care utilization.

Personality disorders were also a significant predictor of readmissions. Personality disorders may increase risk of readmission secondary to illness burden, comorbidity, or suicidality and other safety factors. Moreover, this association might reflect that youths with frequent readmissions and suicidality are more frequently diagnosed as having personality disorders. In turn, youths with personality disorders may also be more frequently categorized as treatment resistant or more severely ill (

5).

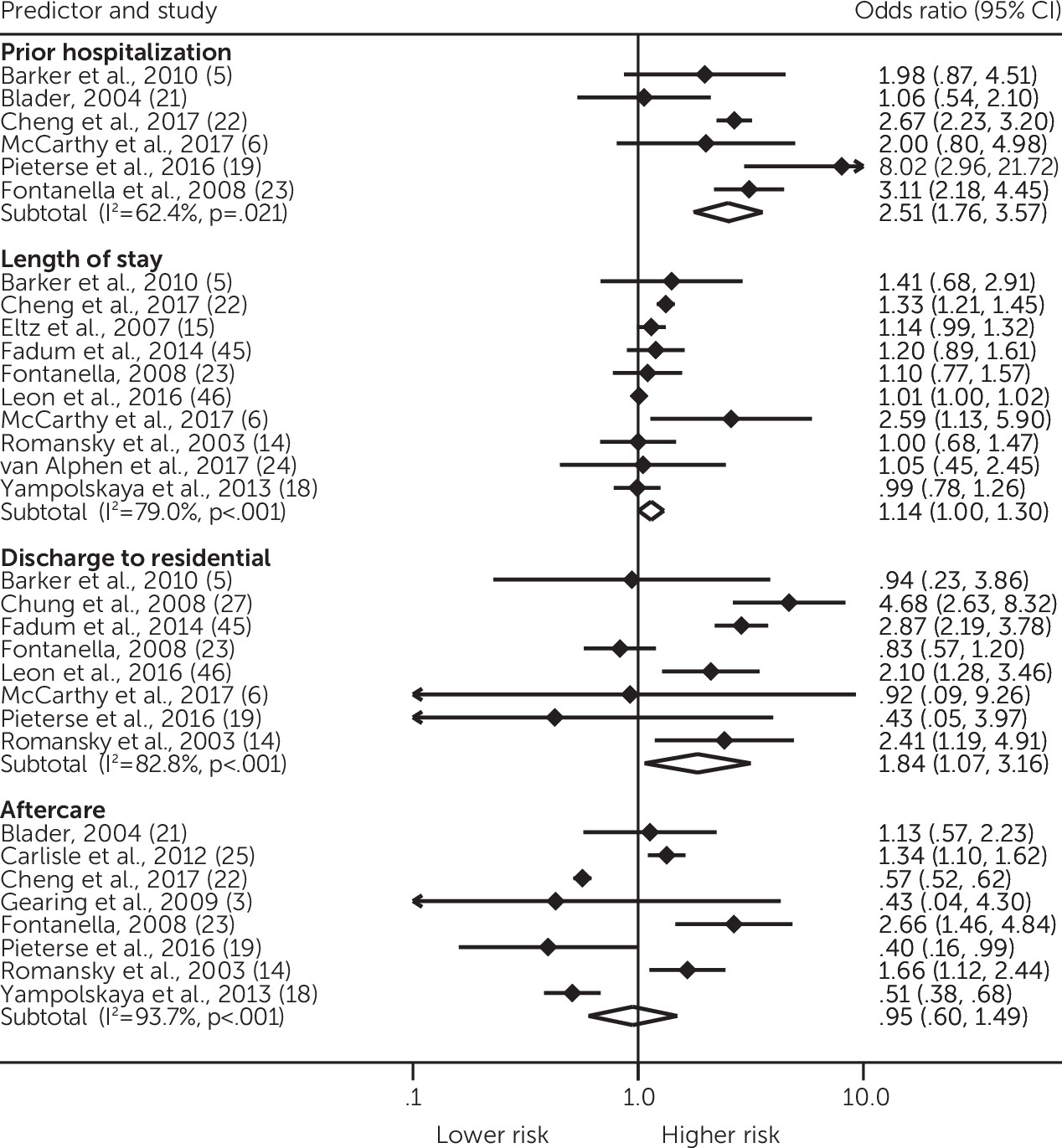

The relationship between clinical severity and readmission was also evident at the hospital level: prior hospitalization, discharge to residential treatment, and longer mean LOS were all associated with readmission. Diagnostic and utilization-related predictors are likely inherently confounded—for example, youths with serious mental illness are more likely to have prior hospitalizations. Across varied inpatient practice settings and diverse cohorts, the studies suggest that youths with higher clinical severity are more likely to experience frequent hospital admissions and early readmission. This may justify increased implementation of resource-intensive postdischarge interventions for severely ill youths to mitigate the costlier alternative of rehospitalization.

The long mean LOS (N=16.6 days) of the included studies may be an indicator of differences in resources across hospital systems reporting data on readmissions compared with those absent from this sample. The LOS may also reflect an evolution in the prevalence of managed care over the past 20 years. Included studies ranged in data collection from 1997 through 2018, and newer studies may more accurately reflect current managed care practices. There was a significant negative correlation between year of study and LOS (r=−0.693, p=0.001), consistent with the evolution of managed care practices over the past two decades. Of note, hospital-level predictors were pooled across a wide range of practice settings, including 11 international studies (Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Norway, China, Denmark, and South Africa) conducted within diverse health systems.

Several limitations of this meta-analysis should be acknowledged. This study describes an association between individual predictors and readmission; no causal inferences or assumption of multivariate adjustment can be made. Although in some cases, individual studies attempted to control for confounding variables, many did not. Potential sources of heterogeneity were explored by using subgroup and meta-regression analyses. Differences in study population and methodology may have contributed to the moderate to high ES heterogeneity of multiple predictors. Results from meta-regression analyses should be interpreted with some caution because of the possibility of type I errors (

36,

37). Study bias was evident in the existing literature, with most studies rated as being at moderate risk of bias, suggesting that negative studies are less frequently published.

Because meta-analysis is inherently limited to predictors previously reported in the literature, this review may be missing potentially important predictor variables, such as type of aftercare interventions, outpatient care, distribution of specific diagnoses in the study population, community resources, various socioeconomic factors and other social determinants of health, and processes of care on the inpatient unit (e.g., medication changes). Several studies reported unexpected results—for example, an inverse relationship between presence of child abuse or neglect and readmissions (

24). Modality of biopsychosocial and diagnostic assessment varied between studies with regard to extent of standardization (e.g., structured versus unstructured interview), and thus sensitivity of assessments across multiple domains likely differed.