In 2017, there were 19.8 million U.S. veterans, of whom approximately nine million were enrolled in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health system, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). Among VHA patients in 2010, approximately 1.8% had received diagnoses of schizophrenia and 2.5% had received diagnoses of bipolar disorder in the prior 24 months (

1). Veterans with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia have substantial ongoing treatment needs, and VHA provides a continuum of care over the life course.

Dementia is an illness with a devastating impact on those affected and their families. In 2010, approximately 36 million people worldwide had dementia, a prevalence that is predicted to increase substantially in the coming decades (

2). By 2040, a total of 81 million people will have dementia (

3). In 2013, among veterans ages 65 and older who used VHA services, 142,951 had a diagnosis of dementia from VHA or Medicare providers. This represented a 7.4% prevalence rate of dementia among older veterans receiving VHA care (

4).

Research has found that persons with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are at increased risk of dementia. Understanding that risk is paramount for treatment as persons with schizophrenia and bipolar illness age. A recent meta-analysis of six studies with over five million participants calculated a relative increased risk of 2.2 times for the development of dementia among those with schizophrenia, compared with those without schizophrenia (

5). In a Danish population-based cohort study, schizophrenia was also found to increase the risk of dementia twofold (

6). In that study, 7.4% of persons with schizophrenia developed dementia prior to age 80, compared with 5.8% of those without schizophrenia. The relative risk was nearly fourfold among those under age 65. Estimates did not change significantly when the analyses adjusted for cardiovascular disease and diabetes.

Bipolar disorder has also been found to be associated with an increased risk of dementia. In a meta-analysis that included 3,026 individuals and six studies (

7), a history of bipolar disorder, compared with no history of bipolar disorder, increased the risk of dementia, with an overall calculated odds ratio (OR) of 2.36 (95% confidence interval [CI]=1.36–4.0). A large cohort study in Australia showed an adjusted hazard ratio for dementia of 2.30 (95% CI=1.80–2.94) among those with bipolar disorder, compared with the general population (

8). A small population-based study demonstrated significant risk of subsequent dementia among patients with bipolar disorder over a 20-year period, after the analysis adjusted for cardiovascular risk factors (

9). An analysis of data from a large Taiwanese database of patients given dementia diagnoses over the course of a decade matched 9,304 persons by gender, age, and index date to those without dementia. In addition, medical conditions, including cerebrovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, head injury, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and substance use disorders were analyzed as covariates. Bipolar disorder was significantly associated with an increased risk of subsequent dementia, with an adjusted OR of 4.32 (95% CI=3.21–5.82), even after the analysis controlled for other comorbidities (

10). Preuss et al. (

11) compared 315,244 inpatient admissions for U.S. patients who were diagnosed as having Alzheimer’s dementia and who were at least 60 years old. After the analysis controlled for age and gender, patients with Alzheimer’s disease (versus those with osteoarthritis) had a higher rate of bipolar disorder (OR=2.78). Kessing and Nilsson (

12) analyzed data from all hospitalized patients in Denmark between 1977 and 1993 and found that those with a diagnosis of unipolar or bipolar depression were at a greater risk of being diagnosed as having dementia at a subsequent readmission. Another longitudinal study of 345 patients with bipolar disorder who were over age 55 found that they had an increased risk of developing dementia, compared with age- and sex-matched persons in a control group, even after the analysis adjusted for medical comorbidities (hazard ratio=5.58, 95% CI=4.26–7.32) (

13).

No previous study has examined the incidence of dementia among VHA patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. To inform VHA operations, the purpose of this study was to characterize the risk of developing dementia among veterans in VHA care and to assess whether incidence differs among those with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, compared with patients with neither condition, with adjustment for comorbid general medical diagnoses.

Methods

Study data were drawn from the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), which includes information regarding inpatient and outpatient care, such as dates of service and clinical diagnoses. Using CDW data, we identified all veterans who received VHA services in both 2004 and 2005, who were between ages 18 and 100 as of January 1, 2006, and who did not have a dementia diagnosis in 2004–2005. Veteran VHA users were identified on the basis of veteran status indicators from VA and the Department of Defense. This project was conducted in support of clinical operations and was approved by the VA Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention.

The cohort was followed for up to 10 years (2006–2015) to assess onset or incidence of dementia. Prior to October 1, 2015, dementia was identified by using the following ICD-9-CM codes: 046.11, 046.19, 046.3, 046.79, 290.0, 290.10–290.13, 290.20, 290.21, 290.3, 290.40–290.43, 291.2, 292.82, 294.10, 294.11, 294.20, 294.21, 294.8, 331.0, 331.11, 331.19, and 331.82. As of October 1, 2015, dementia was identified by using the following singular ICD-10 codes: A8100, A8101, A8109, A812, A8189, A819, F0390, F0391, F1027, F1997, G231, G300, G301, G308, G309, G3101, G3109, G3183, and G903; the following code combinations were also used: B20, G10, G20, and G912, with F0280 or F0281 or a primary diagnosis of I6 with a secondary diagnosis of F0280 or F0281.

We assessed whether participants had a diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder during the baseline period. This was categorized as bipolar disorder, schizophrenia disorder, or neither condition (“no serious mental illness”) on the basis of the most frequent diagnosis in the baseline period, 2004–2005. Individuals with an equal number of encounters with diagnoses of schizophrenia and of bipolar disorder were categorized as having schizophrenia. Bipolar disorder was identified by using the following ICD-9-CM codes: 296.0, 296.1, and 296.4–296.8. Schizophrenia was identified by using the following ICD-9-CM codes: 295.0–295.9. Covariates included age as of January 1, 2006 (categorized as 18–49, 50–64, 65–79, and 80–100 years) and sex.

Analyses were specific to ongoing VHA users, assessed based on date of last VHA use. The outcome for this study was incident dementia, defined as the first ICD-9-CM or ICD-10 dementia diagnosis recorded during the follow-up period. In survival analyses, individuals were censored at whichever came first: death; age 100; the end of the study period; or the date of last use through 2015, if the person had no VHA use in 2016.

Next, baseline general medical comorbid conditions as well as substance use disorders were included in multivariable models of incidence rate ratios (IRRs). These included cerebrovascular disease (ICD-9-CM codes 431, 434.01, 434.11, and 434.91), diabetes (250), essential hypertension (401), dyslipidemia (272), traumatic brain injury (800, 801, 803, 804, and 850–854.1), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (416.8, 416.9, and 490–498), alcohol use disorder (291, 303.0, 303.9, and 305.0), drug use disorder (292, 304, and 305.2–305.9), tobacco use (305.1, 649.0, and 989.84), renal diseases (403, 404.02, 404.12, 404.92, 582, 583, 585, 586, 588, and 593.9), ischemic heart disease (410–414), and congestive heart failure (428).

Survival curves were created to assess dementia-free survival by diagnosis and age group by using the actuarial method. Poisson regression was used to model the IRR of dementia by serious mental illness diagnosis, age, and sex. Baseline comorbidities were added to the multivariable model to calculate IRRs.

Results

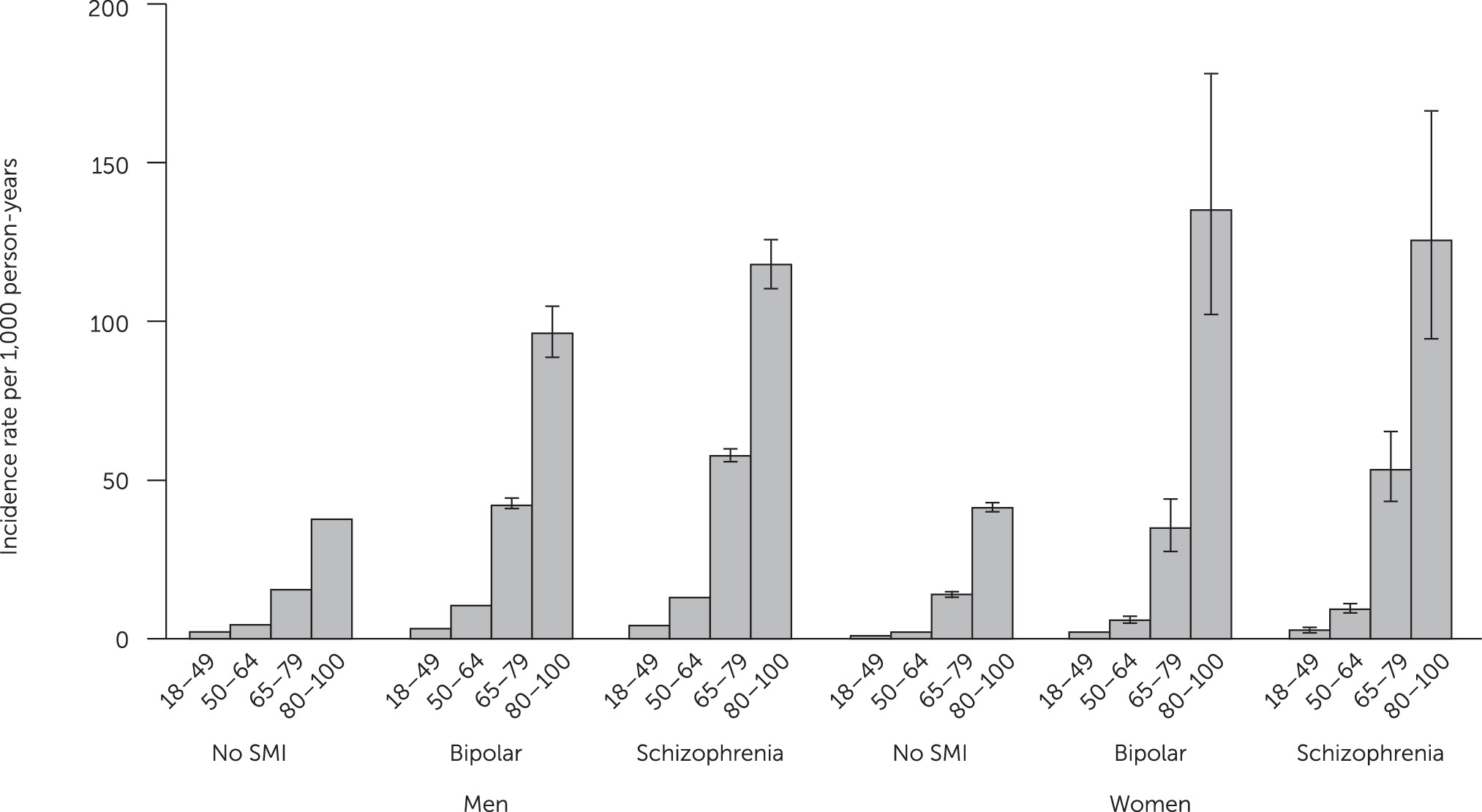

A total of 3,648,852 veteran VHA patients were included in the study cohort: 3,407,752 men (93%) and 241,100 women (7%). Most individuals had no diagnosis of either bipolar disorder or schizophrenia (96% of men, and 93% of women). The incidence of dementia per 1,000 person-years was calculated by gender, age group, and diagnosis. For men with bipolar disorder, the mean incidence of dementia per 1,000 person-years was 11.5, and for men with schizophrenia it was 15.1, compared with the mean of 11.2 for the control group (

Table 1). For women with bipolar disorder, the mean incidence of dementia per 1,000 person-years was 4.1., and for women with schizophrenia it was 8.4, compared with the control group mean of 4.0. Findings by age group for men and women are also presented in

Figure 1. Among veterans diagnosed as having dementia during the follow-up period, the mean±SD age at first recorded dementia diagnosis was 78.8±9.6 for individuals with no serious mental illness, 67.9±11.0 for those with bipolar disorder, and 68.5±10.9 for those with schizophrenia.

The IRRs were calculated on the basis of the baseline diagnosis, gender, and age and were adjusted for general medical comorbidities and substance use disorders that can contribute to dementia risk (

Table 2). Even after the analysis accounted for general medical comorbidities, the IRRs for dementia were higher for veterans with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, compared with those with neither diagnosis. The overall IRR after adjusting for age and sex was significantly higher for veterans with a baseline diagnosis of schizophrenia (IRR=2.92, 95% CI=2.86–2.98) and for veterans with a baseline diagnosis of bipolar disorder (IRR=2.66, 95% CI=2.20–2.31) as compared with veterans with no serious mental illness.

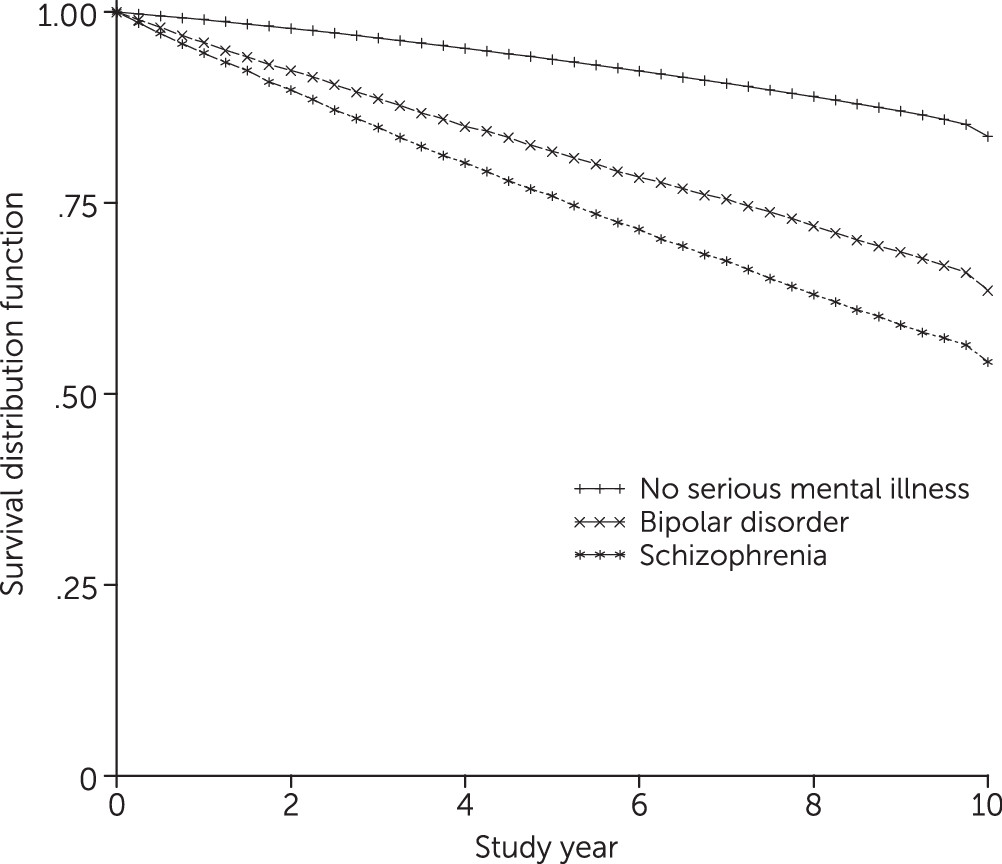

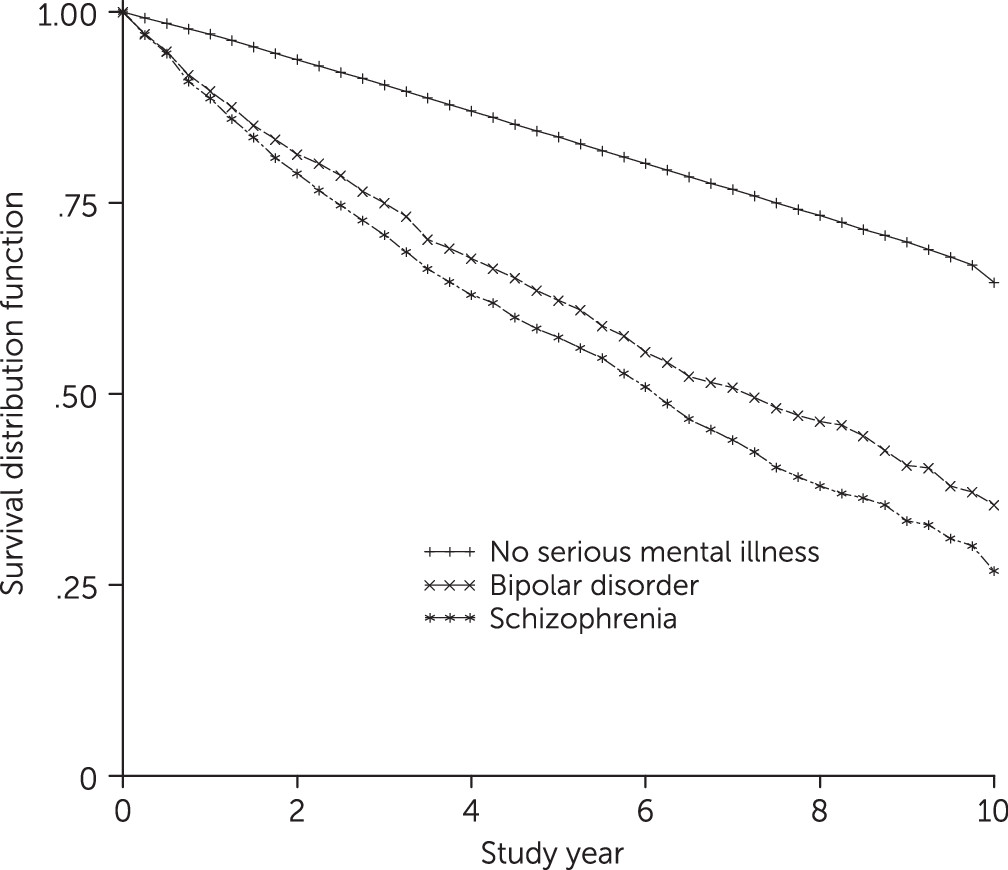

Figures 2 and

3 show dementia-free survival in the older age groups for men and women combined.

Discussion

The VHA serves an aging patient population, and it is important to understand risk factors for incident dementia among VHA patients. The study reported here confirmed prior studies indicating that individuals with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia have increased risk of dementia onset, even when the analysis controls for general medical comorbidities. For both illnesses, the IRRs for patients with these conditions were higher than for patients with neither condition. Individuals with schizophrenia were at highest risk of developing dementia.

Our understanding of why dementia develops at a higher rate among those with schizophrenia is incomplete. Schizophrenia is associated with a wide range of cognitive deficits that can be severe and enduring. Seidman et al. (

14) demonstrated significant and clinically meaningful neurocognitive deficits in attention, working memory, and declarative memory during the prodromal phase of schizophrenia among persons who went on to develop psychosis. A study of stabilized patients with first-episode psychosis found significant memory deficits in addition to motor and executive dysfunction, compared with a control group (

15). In addition, severe neurocognitive deficits have been demonstrated to continue in the chronic phases of schizophrenia, with 61%−78% of patients in one study scoring below the median on a wide range of neurocognitive measures (

16). Therefore, it is possible that patients with schizophrenia have cognitive and functional changes that are consistent with dementia over their lifespan and that they are only formally diagnosed as having dementia at a later age. Some studies suggest that in addition to being a neurodevelopmental condition, schizophrenia may be a neurodegenerative disorder (

9,

17). Lyketsos and Peters (

18) suggested that only a subpopulation of persons with schizophrenia develop a neurodegenerative disorder, reflecting the heterogeneity of the disorder.

Increased general medical comorbidity has been found among persons with schizophrenia, including medical conditions that are independent risk factors for dementia. These include diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, ischemic heart disease, congestive heart failure, and substance abuse (

19–

23). Yet this study and other studies have found an increased risk of dementia even after analyses controlled for medical comorbidities (

24).

In a postmortem study, neuropathologic findings among persons with schizophrenia were different from findings among those with Alzheimer’s disease, with high neurofibrillary tangle density (corresponding to dementia) but lower than expected neuritic plaque findings (

25). The neuropathology of dementia may be different in important ways.

Similarly, the higher rates of dementia in bipolar disorder are as yet unexplained. Although baseline cognitive impairment has been demonstrated among about 30% of patients with bipolar disorder (

26), longitudinal studies have failed to show evidence of neuroprogression (

27–

30). If baseline cognitive impairment does not inevitably lead to neuroprogression, there may be an increased overall risk of dementia. In addition, more refractory forms of bipolar disorder appear to be a risk factor, because a higher number of lifetime affective episodes have been associated with an increased risk of dementia (

27,

31).

Medical comorbidities in bipolar disorder are serious and common and include metabolic syndrome, hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and endocrine abnormalities (

26,

32,

33), as well as substance use disorders (

34). These comorbid conditions can contribute to the risk of dementia. Psychiatric medications used to treat bipolar disorder can also contribute to medical comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disorders, which in turn increase the risk of dementia. Moreover, the intensity of medical care may be lower for persons with bipolar disorder. At least one study noted a lower rate of prescribing for coronary heart disease and hypertension among these patients (

35). Finally, negative health behaviors seen in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, such as poor diet, lack of exercise, and tobacco use, can also increase the risk of dementia (

7).

In bipolar disorder, there is compelling preclinical and clinical evidence that lithium has neuroprotective properties. Diniz et al. (

36) summarized the potential mechanisms of lithium, including the inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase, leading to a reduction of amyloid beta 42 production and tau protein phosphorylation. Lithium has also been shown to increase brain-derived neurotropic factor (

37,

38) and increase the volumes of the hippocampus and amygdala (

39). Moreover, higher white matter integrity has been demonstrated among older adults with bipolar disorder who remained on lithium (

40). In a 10-year study, Kessing et al. (

41) compared persons who purchased lithium at least once to a random sample from the general population and found that continued lithium treatment was associated with a reduced incidence of dementia, approaching that of the general population. Lithium, therefore, appears to have substantial potential to lower risk of dementia among patients with bipolar disorder.

Primary care and mental health clinicians should be educated about the elevated risk of dementia among VHA patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, as suggested by this study. They should be alert to memory or other cognitive complaints in this patient population and should initiate an evaluation for dementia when there are signs or symptoms of possible cognitive impairment. Possible prevention of dementia is also critical. Cardiovascular risk factors, such as smoking, diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, should be clinically managed to help mitigate the risk of dementia. Clinicians choosing medication treatment for schizophrenia or bipolar disorder should be aware of the increased risk of dementia and if possible select medications that will not increase cardiovascular risk.

This study had several limitations. We did not account for onset, course, or duration of psychiatric illness. No baseline measures of neurocognition or longitudinal measurements were conducted. The intensity of psychiatric and medical care was not measured, and we did not evaluate the potential contribution of psychiatric medication exposure. Future studies should account for these potential factors in their analyses because they may affect the risk of dementia.

Conclusions

This study of more than 3.6 million U.S. veterans in VHA care demonstrated an increased risk of dementia among those with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, even after the analyses controlled for general medical comorbid conditions. VHA clinicians should be educated on the potential elevated risk of dementia among VHA patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder and should be encouraged to evaluate for possible dementia when there are signs or symptoms of cognitive impairment in this patient population. Prevention of dementia in these populations is critical and includes management of comorbid health conditions that can increase risk of dementia and careful choice of medications that do not increase cardiovascular risk. Lithium may be a promising agent in the prevention of dementia in bipolar disorder. Recommendations for providers working with persons with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder may be applicable to those working with persons from the general population.