Unlike quality measurement in general acute care hospitals, for which there is an overabundance of measures and measurement programs, quality measurement in inpatient psychiatric facilities is in its nascence (

1–

3). In the fall of 2012, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) debuted the Inpatient Psychiatric Facility Quality Reporting (IPFQR) program, a pay-for-reporting program for inpatient psychiatric facilities (IPFs). This program includes structural and process measures that IPFs must collect and submit to CMS, as well as claims-based measures that do not require data collection (

4). Quality measures from this program are publicly reported on the Hospital Compare Web site, alongside quality measures from the CMS quality reporting program for general acute care hospitals, and IPFs that fail to participate incur financial penalties (

4).

A large body of literature describes the merits and limitations of measures included in public reporting programs for nonpsychiatric inpatient facilities. For instance, readmission measures are common in quality measurement programs. Structures and processes of inpatient care have been found to affect readmission rates, suggesting that these rates can serve as proxy measures for the quality of inpatient care. Performance across facilities with similar characteristics often varies widely, suggesting opportunities for improvement (

5–

9). However, superior hospital performance on readmission measures has been found to be associated with greater upcoding (

10), higher mortality rates (

11), and patients’ higher socioeconomic status (SES) (

12).

Little evidence has been found to support an association between hospital performance on process measures and measures of the outcomes that these processes are designed to affect, including care coordination process measures and readmission outcome measures (

13–

20). In theory, process measures, which aim to measure compliance with evidence-based processes, should reflect the quality of clinical care at an institution and thus should be associated with care outcomes (

21). In practice, process measures often fail to capture essential elements of evidence-based processes because the feasibility of measuring them, and thus the ability of these measures to reflect true clinical quality, is limited (

21).

Little research has been conducted on the strengths and limitations of the measures in the IPFQR program. Since its inception, care transitions have been a major theme in this program. The program includes process measures of discharge plan development, discharge plan transmission, follow-up appointment attendance, and, most recently, readmissions (

22,

23). The 30-day all-cause unplanned readmission following psychiatric hospitalization (READM-30-IPF) metric measures the rate at which Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries who are discharged from IPFs are readmitted to any inpatient facility for any unplanned general medical or psychiatric reason within 30 days of the discharge (

23).

Our objective was to explore variation in the READM-30-IPF and to examine the association between this new psychiatric readmission measure and IPFQR care coordination process measures. We hypothesized that better facility-level performance on IPFQR care coordination measures would be associated with better performance on the readmission measure (i.e., the READM-30-IPF).

Methods

Data Source and Sample

We used data from the February 2019 Hospital Compare IPFQR data release. This data release was the first that made facility-level readmission rates publicly available, and these rates were based on discharges that occurred from July 2015 to June 2017 (

23). We merged this file with the 2017 and 2018 Hospital Compare IPFQR measure files (reflecting performance in 2015, 2016, and 2017), the 2015 American Hospital Association (AHA) annual survey to capture hospital-level characteristics (

24), and the 2015 Area Health Resource File (AHRF) to capture community-level characteristics of the counties in which an IPF was located (

25). Institutional review board approval was waived, because all data sets are publicly available.

The February 2019 IPFQR data file contained 1,631 IPFs, of which 1,513 (93%) had readmission scores. A total of 67 (4%) did not have scores because their number of eligible discharges was too small, and 51 (3%) lacked scores because they had no Medicare claims for this period or had elected to suppress the measure from public reporting. Of the 1,513 IPFs with readmission scores, 74 did not have data on one or more IPFQR care coordination measures (more details are included in an online supplement to this article). A total of 91 were not listed in the AHA annual survey. Five IPFs did not have corresponding demographic information in the AHRF. Our final sample therefore was 1,343 IPFs (89% of the population). Compared with IPFs that were excluded from the study because of missing data, the included IPFs had significantly more discharges eligible for the readmission measure (412 vs. 297, p<0.001); however, no statistically significant difference was noted in readmission rates (20% for included IPFQR programs vs. 20% for those excluded).

Measures

READM-30-IPF.

The READM-30-IPF measure assesses the rate of readmissions for Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries discharged from IPFs and includes readmissions for both psychiatric and medical conditions (see

online supplement for details). This measure was added to the IPFQR program by the federal rule published on August 22, 2016, and has been endorsed by the National Quality Forum (

26).

Encounters are excluded from the measure when patients are discharged against medical advice, transferred, readmitted to the same psychiatric facility within 2 days of discharge, or have planned readmissions (

23,

27–

29). The readmission measure is risk adjusted for age, gender, principal discharge diagnosis for the index admission, medical and psychiatric comorbid conditions, history of suicide attempt or self-harm, aggression, or discharge against medical advice. The comorbid condition and history risk factors are based on claims from the index admission and from the 12 months before admission (

23,

27). The rate that CMS publicly reports is already risk adjusted and combines readmissions for general medical and psychiatric causes.

Hospital and community characteristics.

We explored variation in hospital-level readmission rates across characteristics that have previously been found to be associated with readmissions, as well as characteristics indicative of external and organizational resources. According to the resource dependency theory, organizations do not always control the resources necessary to succeed (

30). Hospital-level characteristics included volume of Medicare fee-for-service discharges eligible for the readmission measure, teaching status, system affiliation, freestanding IPF or a psychiatric unit in a general hospital, ownership status, hospital size (number of beds), and Medicaid fraction (i.e., the percentage of all discharges covered by Medicaid) (

31–

33). Hospital size and Medicaid fraction included nonpsychiatric beds in the general acute care hospitals. Community-level characteristics included population density, percentage of county residents living in poverty, percentage of black or Hispanic county residents, number of psychiatrists per 10,000 residents, and number of federally qualified health centers or community mental health centers per 10,000 residents (

5,

33,

34).

Care coordination measures.

We also examined the relationship between hospital performance on the new readmission measure and the two sets of care coordination process measures in the IPFQR program: the transition record measures and the follow-up after hospitalization (FUH) measures (see online supplement for details).

The manually abstracted transition record measures assess whether inpatient providers completed a discharge plan with 11 specific components (transition 1) and whether that discharge plan was transferred to the next level of care provider within 24 hours of discharge (transition 2) (

35). For a record to be compliant with the transition-2 measure, it must first be compliant with the transition-1 measure. The denominator for the two measures is the same (

36–

38). IPFs began data collection for the transition record measures in January 2017, and annual rates are publicly reported. We included facility-level scores from the January–December 2017 reporting period in our analysis.

The FUH measures are claims-based measures that assess the rate of follow-up with a mental health provider within 7 days (FUH-7) and 30 days (FUH-30) of discharge from an IPF for Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries (

35,

39). FUH performance is reported annually. We used consolidated data from the July 2015–June 2016 and July 2016–June 2017 measurement periods to align with the reporting period for the readmission measure. If IPFs had missing data in 1 of the 2 years, we used data from the available year.

Data Analysis

We first calculated descriptive statistics for IPFQR measure performance for all IPFs with publicly reported readmission rates and examined the geographic variation in performance. Then, for the IPFs in our analytic sample, we explored variation within groups (e.g., teaching hospitals) by using means, SDs, and ranges and variation across groups by using Welch’s t tests for analysis of two groups and analysis of variance for three groups. Continuous variables were categorized into terciles. We also explored the correlation between hospital performance on the care coordination measures and the readmission measure. Because the readmission measure had a fairly normal distribution across IPFs (see online supplement), we used a linear regression model to measure the association between IPF-level readmission rates and performance on the care coordination measures included in the IPFQR program, while controlling for hospital and community characteristics. We limited our key independent variables to FUH-7 and the discharge plan transmission measure (transition 2) because these measures capture compliance with their partner measures. We also found significant variation across states and thus present our models with and without state as fixed effect.

We conducted sensitivity analyses by using the FUH-30 and transition-1 measures as our key independent variables, running separate models for the FUH-7 and transition-2 measures, and by using logistic regression to compare low-readmission to high-readmission IPFs and obtained similar results. All analyses were conducted in STATA 15/IC, and p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

As noted above, 1,513 IPFs had publicly reported READM-30-IPF rates (see online supplement). The mean±SD IPF-level rate was 20%±3% and ranged from 11% to 36%. IPFs with publicly reported readmission rates had an average FUH-7 rate of 30% and an average FUH-30 rate of 53%. On average, facilities created and transmitted plans for 47% of discharges (transition 2).

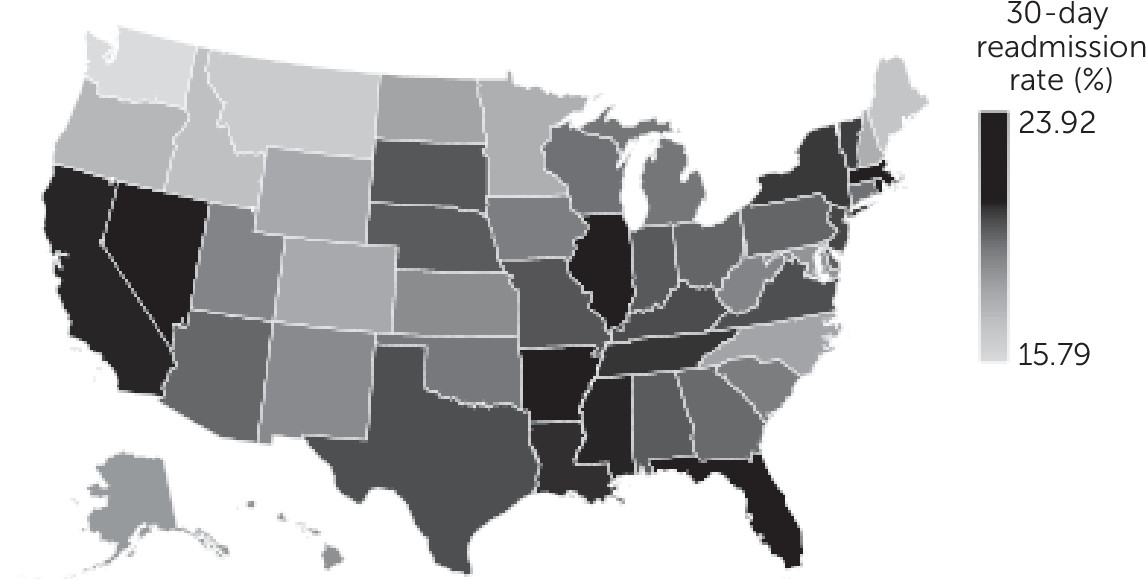

We found large variation across states as shown in the map in

Figure 1 (see also maps in the

online supplement). We found that mean READM-30-IPF rates were lowest in Washington (16%), Minnesota (18%), and New Hampshire (18%) and highest in Rhode Island (24%) and Florida (24%). FUH-7 rates were highest in New Hampshire (54%) and Maine (46%) and lowest in Nevada (17%) and Mississippi (17%). Transition record transmission was highest in Nebraska (75%) and Arkansas (72%) and lowest in the District of Columbia (10%) and Washington (15%).

In

Table 1, we present data on the characteristics of the 1,343 IPFs in our sample. Performance on the IPFQR measures did not markedly differ between our sample and the larger population (N=1,513).

Table 2 presents data on the variation in readmission measure performance across hospital-level and community-level characteristics. Substantial variation in these characteristics appeared to be present within groups. We also compared mean READM-30-IPF rates across categories and observed lower rates in IPFs that were freestanding psychiatric hospitals (compared with units in general hospitals), public hospitals (compared with nonprofit and for profit), facilities located in micropolitan areas (compared with metropolitan and rural areas), and facilities located in counties with lower percentages of residents in poverty and lower percentages of black or Hispanic residents. We also found lower mean readmission rates in IPFs with fewer discharges eligible for the readmission measure and in hospitals with a smaller percentage of discharges of patients covered by Medicaid.

Table 3 presents results of analyses of the relationship between performance on the care coordination process measures and the readmission measure. We found a slight correlation between FUH-7 and FUH-30 and performance on the readmission measure but no correlation between performance on the discharge plan measure (transitions 1 and 2) and the readmission measure. On average, hospitals with top tercile FUH-7 and FUH-30 performance had slightly better performance on the readmission measure.

In

Table 4, we present the results of regression models with and without state as fixed effect. Coefficient direction and statistical significance were similar for both models. In the state as fixed-effects model, IPFs in the top tercile of performance on FUH-7 had on average a readmission rate that was 0.58 percentage points lower than those of IPFs in the bottom tercile. No significant differences in readmission rates were noted between hospitals in the bottom and top terciles of the discharge plan transmission measure (transition 2).

System-affiliated hospitals, freestanding psychiatric hospitals, and public hospitals had lower readmission rates than those not affiliated with a system, units in general hospitals, and for-profit hospitals, respectively. Readmission rates trended upward as the number of discharges eligible for the measure increased; however, readmission rates trended downward as overall hospital size increased. Readmission rates trended upward as the percentage of black or Hispanic county residents increased and as the percentage of hospital discharges of Medicaid-covered patients increased.

Discussion

We found significant variation in 30-day all-cause readmission rates within and between groups, and by states, hospital-level characteristics, and community-level characteristics. This variation indicates likely substantial opportunity for IPFs in each group that we examined and for many states to reduce their readmission rates. However, it is unclear from the data that CMS makes publicly available whether the opportunities for improvement are greatest for readmissions for general medical conditions or for psychiatric conditions because only the combined measure is presented on the Hospital Compare Web site (see online supplement).

A large body of literature describes the causes of psychiatric readmissions after psychiatric hospitalization and outlines evidence-based strategies to prevent these readmissions (

40–

43), but very little literature reports on general medical readmissions after psychiatric hospitalizations. In the absence of research on why patients are medically readmitted after psychiatric hospitalizations and how psychiatric facilities can reduce these readmissions, the value of reporting all-cause readmission rates after psychiatric hospitalization is currently unclear. We recommend that CMS publicly report these rates separately to determine whether both are meaningful measures of the quality of psychiatric care. Mental health consumer groups, such as the National Alliance on Mental Illness, must also be included in these discussions. If marked variation in general medical readmissions after psychiatric hospitalization is noted across hospitals with similar characteristics, research will be needed to determine whether structures and processes that are capable of improving these outcomes can be implemented.

Similarly to studies of quality improvement programs in general acute care hospitals (

13–

15), our study also found little association between process and outcome measures. We found no association between facility performance on the discharge plan measures and the readmission measure and only a modest association between facility performance on the follow-up measures and the readmission measure.

This lack of an association between process and outcome may be related to the design of the measures (

44). The care coordination processes being measured have been found to reduce readmissions for psychiatric causes (

45) but not readmissions for general medical causes. The inclusion of readmissions for general medical conditions in the outcome measure may be hiding a process-outcome association. In addition, like all process measures, those in the IPFQR program can capture only aspects of the process that can feasibly be measured. The discharge plan creation measure examines whether 11 specific data elements are included in a paper document, but it does not measure whether the document was reviewed with the patient and includes correct information. The discharge plan transmission measure examines whether the plan was sent, but it does not assess whether this information was received (

46,

47). CMS may want to consider including a postdischarge survey in the IPFQR program to assess the quality of the care transition process from the perspective of the patient, similarly to the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems survey (

48).

Using claims to measure follow-up with mental health providers after psychiatric hospitalization may also weaken the association between follow-up and readmission. The percentage of patients who receive mental health follow-up appointments that are billed to Medicare likely varies across facilities (

49). Only 55% of U.S. psychiatrists accept Medicare, and this percentage varies by region (

50). Moreover, we found superior performance on the readmission measure among public IPFs; however, public IPFs have previously been found to have significantly poorer performance on the FUH-7 measure (

39). Patients being discharged from public IPFs, particularly from state psychiatric facilities, may be more likely to receive follow-up care at public mental health service providers that do not bill Medicare. A postdischarge survey may also be the only way to accurately capture this phenomenon.

Interestingly, this study also found that IPFs in the lowest tercile of Medicare psychiatric discharges had the lowest readmission rates. The positive relationship between volume and outcomes is well recognized in many facets of medical care, including psychiatry (

51–

54). However, this relationship has not been found consistently for readmissions (

32), perhaps because greater volume means less time spent with each patient or shorter lengths of stay (

32). The length of stay of psychiatric inpatients has consistently been found to be inversely correlated with readmission rates (

55–

57). Medicare beneficiaries admitted to freestanding psychiatric hospitals have been found to have longer stays than Medicare beneficiaries admitted to psychiatric units in general hospitals, which may have contributed to the superior performance of freestanding facilities on the readmission measure (

49). CMS currently does not publicly report mean length of stay, but reporting this metric could be valuable for both clinicians and policy makers.

Several limitations of the study are worth noting. First, the study was cross-sectional. Therefore, one cannot make any causal inferences about the relationship between process and outcomes. Similarly, because the unit of analysis was the facility, caution should be used in applying these findings to individual patients. The READM-30-IPF measure uses data only from Medicare fee-for-service claims, and results cannot be generalized to IPF performance for patients with other payers. Our findings cannot be generalized to the 170 IPFs with missing data that we excluded from our analysis. The study could not determine the association between hospital performance on the care coordination process measures and the readmission rate for psychiatric conditions because CMS publicly reports a combined all-cause readmission rate.

Conclusions

Quality measurement in inpatient psychiatric care is in its early stages. The IPFQR measures have only recently been integrated into the general hospital lookup section of the Hospital Compare Web site, instead of residing in interactive spreadsheets on a separate section of the site (

22,

39). Because these measures will certainly receive increased attention, it is important that they are designed to accurately capture processes and outcomes that are meaningful to individuals with psychiatric illnesses and to identify IPFs that provide high- and low-quality care (

58).