The Prison Policy Initiative (

1) has documented the difficulty of gaining employment for individuals who have spent time in prison. According to their 2018 report, the unemployment rate of formerly incarcerated individuals in 2008 (the most recent year for which data are available) was 27.0%, almost five times the rate of the general public. This circumstance leads to poor income, with as many as 45% of formerly incarcerated individuals not reporting earnings in the year after their release (

2). To address this disparity, various work reentry and supported employment programs have been developed.

Individual placement and support–supported employment (IPS-SE) is a promising model based on several core principles (

3,

4): eligibility based on choice, a focus on competitive employment, integration of mental health and employment services, attention to individual preferences, work incentives planning, rapid job search, systematic job development, and individualized job supports. Although IPS can be, and has been, adapted to better meet the anticipated needs of the population of interest, the preservation of these eight principles should be prioritized. In fact, IPS-SE programs scoring higher on standardized scales of fidelity to the evidence-based IPS model have been shown to produce significantly better competitive employment outcomes compared with programs with lower fidelity scores (

5).

IPS-SE Uses and Application

IPS-SE has been used in studies with individuals from a variety of populations, including those with serious mental illness (

6), spinal cord injuries (

7), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (

8), and substance use disorders (

9), as well as returning veterans (

10). More recently, the number of hybrid or enhanced programs that combine supported employment with another standardized vocational program (

11,

12) or other therapeutic modalities (

13) has increased.

In a meta-analysis and review of IPS populations, Bond et al. (

14) found broad evidence for the utility of supported employment across both traditional and nontraditional populations. However, several limitations were identified in the nontraditional studies, including relatively small samples, uncertain fidelity to the evidence-based supported model of IPS, and a limited number of controlled trials. Overall, IPS for veterans with PTSD offered the strongest evidence for support.

IPS-SE has been adapted for formerly incarcerated individuals. Bond examined the utility of IPS with justice-involved individuals with severe mental illness. A 1-year follow-up showed that 31% of IPS participants obtained competitive employment, compared with 7% in the comparison group (

15). LePage et al. (

16) applied a hybrid program of preemployment vocational classes and the principles of IPS-SE to facilitate vocational rehabilitation of formerly incarcerated individuals. In a 6-month follow-up study, they found that veterans who received vocational reintegration classes followed by IPS were significantly more likely to obtain employment than were veterans participating in only vocational classes.

The current randomized prospective study extends the work of LePage et al. (

16) by evaluating a hybrid program that combines IPS-SE and standardized group-based vocational rehabilitation. The study used a novel sample and followed participants for 12 months. We hypothesized that those receiving the combination of services would have higher rates of employment, become employed quicker, and have higher rates of stable employment (i.e., employed with the same employer for 3 continuous months) compared with participants in the group-based program alone.

Methods

Participants

A total of 146 veterans with a history of a prison incarceration and either a mental illness or substance use disorder were screened for the study at a large U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care facility. Inclusion criteria—having a felony conviction and a mental illness, substance use disorder, or both—were left broad to improve generalizability. Exclusion criteria were active psychosis or cognitive impairment precluding participation. Inclusion criteria were assessed through self-report and medical records, and a doctorate-level psychologist determined which veterans met exclusion criteria. Ultimately, 111 veterans (108 males and three females) participated in the analyses (see online supplement).

A majority (N=90, 81%) of the veterans had a substance use disorder. Fifty-nine percent (N=65) of the sample experienced current homelessness, and 52% (N=58) met the definition for chronic homelessness. Seven veterans in each condition had a service-connected disability. The mean±SD rate of having a service-connected disability for the vocational group only was 30%±20% and for the group with IPS-SE was 21%±21%. No participants were receiving Social Security Disability Insurance or had a disability that was unrelated to their military service. The study was approved by the VA North Texas Health Care System’s institutional review board.

Procedures

Veterans were recruited over 26 months between 2012 and 2015. A total of 27 vocational groups were conducted. The average number of veterans per group was 4.0±1.5, and between one and seven veterans completed each group. Groups were mixed with participants who would receive only the About Face Vocational Program (AFVP) and those who would receive AFVP and IPS-SE (AFVP+IP-SE). Groups were co-led by two vocational rehabilitation specialists. Each vocational rehabilitation specialist had specific training in the AFVP.

Supported employment was the responsibility of one primary staff member, with a second staff member providing as-needed backup. Both staff members had master’s degrees in rehabilitation counseling and advanced training in vocational rehabilitation counseling. Staff members had received training in IPS-SE through formal educational coursework, as part of a national VA training program for IPS research projects, or both.

All veterans were given a baseline assessment, which included questions about demographic information, housing status, legal history, and employment history. Diagnostic information was obtained from medical records. After the baseline assessments and interview were completed, all participants were randomly assigned to either AFVP or AFVP+IPS-SE.

AFVP.

The AVFP is a 1-week, manualized vocational group providing vocational reintegration strategies as well as specific modules focused on overcoming the employment consequences of incarceration. Veterans in the class met for 8–10 hours over the course of 1 week. The AFVP has been determined to achieve better outcomes compared with self-help protocols or receiving no services (

17).

The classes were provided in a standardized format following the

About Face Vocational Manual, which is described in detail elsewhere (

17). Participants worked through a standardized vocational manual and discussed their responses to the manual in the group. The classes focused participants on identifying and developing concrete examples of their skills. Veterans also developed strategies for honestly discussing incarceration and legal difficulties, gaps in employment, disruptions to work history, and short-term employments. Resumes, tailored to the veteran, were created, and specific job search strategies were developed.

At enrollment, participants performed a videotaped practice interview. After the groups met, participants performed a second practice interview. The group members watched the interviews during the last class, and the instructor reinforced areas of success and helped participants identify areas in need of improvement.

AFVP+IPS-SE.

Participants in the AFVP+IPS-SE condition completed the same class and procedures as those in AFVP only. After completion, the participants were assigned a supported employment specialist (SES) who delivered the IPS-SE. The caseloads for the SESs were approximately 30 active participants, with varying levels of services provided.

The IPS-SE delivered intentionally differed from published best practices of evidence-based supported employment (

4,

18) in several ways, including larger than recommended caseloads, relatively low integration with specific treatment teams, some exclusion criteria (i.e., interfering psychosis or cognitive impairment), requiring class attendance before receiving a SES, and a focus on “conviction friendly” professions. Overall, the program was not expected to meet all standards of evidence-based supported employment. Fidelity ratings were assessed based on anchors created by the IPS Employment Center (

19).

Data Collection

Veterans in both conditions were expected to contact study staff twice a month, once face-to-face and once by phone, to complete surveys and update their job search results. If the participant reported employment, the employment was confirmed by study staff through a review of pay stubs, community visits, contacts with employers, or other means. Veterans were compensated for follow-up contacts only; they were not compensated for job search activities or job procurement. Substance use during the study was assessed through patient report and chart notes.

Statistical Analyses

Continuous parameters were reported as mean±SD. Discrete parameters were reported as N and percent. Shapiro-Wilk tests were used to test for normality in continuous dependent variables. Continuous parameters were compared by using Mann-Whitney U tests, and discrete parameters were compared by using the Pearson chi-square test. Generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) were computed to examine differences in outcomes between the conditions, with participants nested within both therapy group and SESs, thereby adjusting for potential correlated observations within the therapy groups. Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were performed to compare the groups in terms of time until accelerated employment. Analyses were performed using SPSS, version 25.0 for Windows.

Results

Participants’ demographic and historical variables presented in

Table 1 were evaluated for inclusion as covariates in the analyses. No significant differences were found between the two groups on any demographic variable. Additionally, although at least one episode of substance use during the follow-up period was common (8%), the incidence rate was similar between conditions.

IPS-SE fidelity was assessed at three points during the study, one time per year. Median fidelity scores for items are presented in

Table 2. On the basis of the study’s limitations and the planed deviations from the evidence-based supported model of IPS-SE, the level of fidelity fell within the “fair” implementation range.

An overview of employment results can be seen in

Table 3. The groups were compared on rates of employment, rates of stable competitive employment, full-time employment, and the number of months employed. GLMM analyses revealed a significant difference between conditions in the rate of employment at 12 months (odds ratio [OR]=2.20, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.03–4.7, p=0.046. At the end of the study year, 57% of veterans in the AFVP+IPS-SE condition had found employment, compared with 37% in the AFVP condition. A significant difference between conditions was found at 12 months in rate of full-time employment, defined as 35 hours or more per week (OR=3.56, p=0.006). At the end of the study year, 43% of veterans in the AFVP+IPS-SE condition had achieved full-time employment, compared with 18% in the AFVP condition. Although results were in the predicted direction, veterans in the AFVP+IPS-SE condition did not have significantly higher rates of stable employment compared with those assigned to the AFVP only, 42% versus 29% respectively. Finally, the veterans in the AFVP+IPS-SE condition worked significantly more months during the study year than those in the AFVP condition (4.2±3.8 versus 2.3±4.6, respectively, t=2.2, df=109, p=0.027).

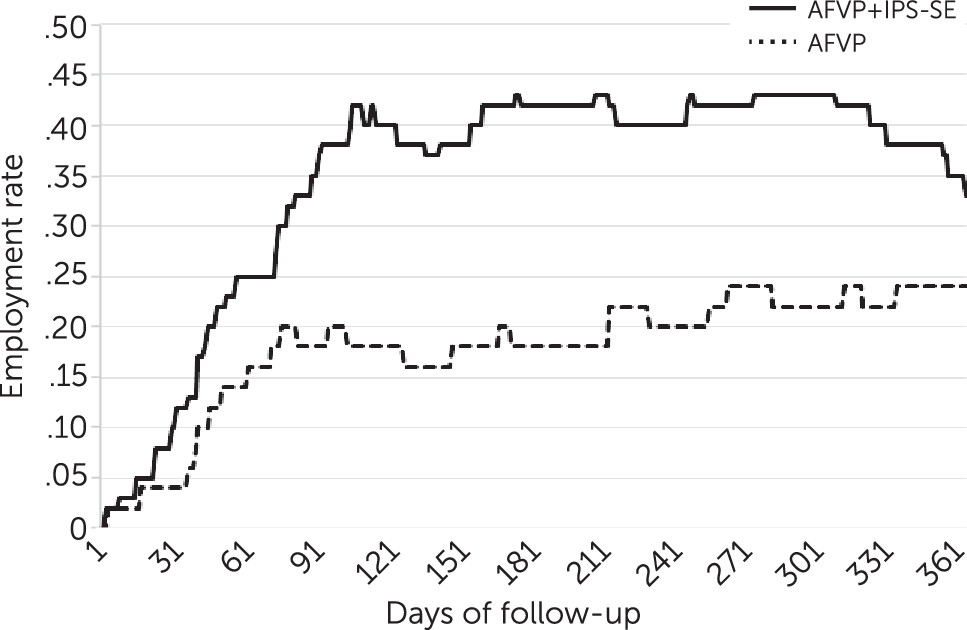

Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were performed for employment at 12 months. The time until employment revealed that participants receiving AFVP+IPS-SE were more likely to have found employment and to have obtained it sooner than veterans in the AFVP condition (χ

2=4.80, df=1, p=0.028) (

Figure 1). The median time to employment for veterans in the AFVP+IPS-SE condition was 192.5 days (mean=210±146) compared with 365 days (mean=277±131) in the AFVP condition.

Rates of employment at each month during the follow-up period were compared.

Figure 2 provides a collapsed view of overall employment over time, accounting for job gain and loss. Total employment in both conditions tended to flatten after 3 to 4 months, where gains and losses in employment begin to balance out.

The 53 veterans from either condition who had achieved employment within 1 year were examined separately for more in-depth analyses. Comparisons of this subset between the two study conditions revealed that the AFVP+IPS-SE condition had a significantly higher proportion of veterans with full-time employment than did the AFVP condition (77% versus 47%, respectively; p=0.032). However, no significant differences were found in other employment outcomes.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to evaluate the 1-year follow-up employment rates of a hybrid program that combines AFVP, a standardized group-based vocational rehabilitation program, with IPS-SE. Although the group-based program has been shown to be an improvement over treatment as usual and self-help methods, we believed that a more targeted approach that included the guided assistance of a supported employment specialist working with both the participant and employer would improve success.

The results confirm and extend previous work. The combined program demonstrated superior vocational outcomes, compared with group alone, across almost all employment measures at the group level. Rates of employment in the AFVP+IPS-SE condition were 52% greater than in group alone, with veterans in the hybrid program finding employment 2 months faster on average than their counterparts. Those in the AFVP+IPS-SE condition worked approximately 288 hours more and earned over twice the income as those in the group-only condition.

We expected the jobs obtained by those in the AFVP+IPS-SE condition would be higher paying, more likely to be full-time, and more stable compared with jobs obtained by veterans in group alone. Those receiving AFVP+IPS-SE had almost twice the rate of full-time employment as their counterparts. Veterans in the AFVP+IPS-SE condition who found employment found their job over a month quicker, worked 33% more hours, and earned almost 50% more over the course of the study than veterans in the AFVP-only condition who found employment, although these results did not reach statistical significance.

The study found similarities in outcomes between conditions within the subset of those who found employment; although underpowered, the findings are consistent with other IPS-SE studies (

20). Additionally, the findings are likely biased, because many of those in the AFVP+IPS-SE condition would not have found employment if they had been assigned to the AFVP condition.

Past studies have demonstrated that programs with “fair” fidelity to the evidence-based supported model have shown superior results compared with control groups (

14); this study, due to several planned and unplanned deviations from the evidence-based supported model of IPS, fell into this fidelity range. The deviations can be divided into three general categories.

The first were planned deviations due to study factors. These included participating in the class prior to engaging the SES portion of the study and the use of some exclusion criteria. Additionally, this study had no direct involvement from facility leadership nor support for the research program.

The second focused on the nature of the population, including participants’ interactions with mental health services. Veterans were recruited from a wide range of sources, including homeless shelters and word-of-mouth recruitment. For many, treatment involved relatively low use of mental health teams (i.e., seeing their mental health team only twice a year). Caseloads were higher in the current study compared with high-fidelity evidence-based supported employment. This deviation appeared acceptable due to the lower rate of psychotic disorders among participants. Additionally, this study focused more than does fully implemented IPS on careers and employment opportunities that tended to be more amenable to hiring those with histories of prison.

The third category of deviations involved the participants’ low desire to have the SES meet with the participants’ mental health team and employers after hiring, a finding noted in a previous study (

16). This pattern continued in the current sample and was noted in the fidelity ratings. The SESs’ more limited contact with employers and treatment teams may have contributed to the lack of difference, noted in

Table 3, between the two conditions in sustaining employment after finding a job.

This study had several strengths. The first was the use of a randomized controlled design. As described in a review of IPS in areas other than serious mental illness (

14), relatively few randomized controlled trails of IPS-related interventions have met adequate levels of scientific rigor. The second strength was that the group-only condition was based on a published effective treatment and not treatment as usual, wait listing, or other low-impact program. This design may have reduced the overall estimate of the effect size but created a stronger validation of the added benefits of IPS.

We identified several limitations to this study. First, as previously discussed, the study deviated from best practices of evidence-based supported employment, as demonstrated by the fidelity ratings. Because studies have demonstrated that fidelity is associated with improved outcomes (

21,

22), a stronger focus on aligning the current study with best practices may have rendered higher rates of employment. Additionally, the population served had low rates of psychotic disorders, resulting in limitations to generalizability. Furthermore, a higher rate of dropouts in the AFVP-only condition may have created biases favoring the control group. Finally, this study was a single-site study under the direction of those who created the AFVP. As such, the portability of the hybrid model has not been assessed.

Several notable lessons from conducting this study and from use of IPS-SE with this population will be of benefit to future programs. First, SESs should exercise patience. Although the SES is primarily focused on employment, participants may prioritize other areas of their lives. It is important for the SES to assist participants in connecting with needed services, to encourage continued employment search, and to help the participant see the benefits of employment to their current situation. The SES’s attempts to focus on employment when employment is not the participant’s priority must emphasize the positives of and encourage engagement in an employment search. Because motivation has been identified as a barrier to success (

23), it is speculated that incorporating motivational interviewing techniques (

24) may be helpful in keeping participants engaged.

Several disruptions encountered during the study need to be anticipated by SESs. The high rate of housing instability in this population (

25,

26) can shift participants’ immediate needs from employment to housing, causing lack of communication with the SES and periods when the location of the participant is unknown. This problem is compounded because many individuals in this population do not have close family to help locate them. There was also a high rate of at least one episode of substance use during the follow-up period. Substance use was frequently the cause of disruption to engagement in IPS-SE services and contact during follow-up.