Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is characterized by persistent deficits in social communication and interaction as well as restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior that begin early in development, with clinical impairment that persists through the lifespan (

1). Countries with low-, middle-, and high-income economies consistently report diagnostic delay for ASD (

2,

3). Parents often notice an abnormal development in their children before the age of 2, but a formal diagnosis is often not reached until many months later (

4). For instance, in the United States, the mean age at diagnosis for ASD is 4 years and for Asperger’s syndrome is over age 6 (75 months), with similar results in Mexico and other Latin American countries (

3,

5). Reducing age of diagnosis is linked to improved access to treatment, a better prognosis for cognitive function, and less symptom severity (

6). These outcomes in turn can mitigate the more challenging aspects of ASD for individuals, their families, and their countries’ health care systems.

Diagnostic delay in ASD is associated with components of the health care system such as the availability of local services, increased demand of specialized professionals (

7), failure in recognition by medical staff (

8), and low rates of referral by primary care providers (

2). In Mexico, the health care system comprises private and public sectors. When accessing private health care, patients cover the cost either out of pocket or by using insurance. These services cover less than 5% of the population (

9). The public sector comprises two sets of institutions. The first set, which is funded by the pooled financial contributions of the government, employers, and employees, provides services to workers belonging to the formal sector of the economy (47%). In these institutions, patients are evaluated by a primary care physician who, in turn, provides a referral to a specialist in the secondary or tertiary level of care. The second set provides services to the population that is without social security benefits (52%). Access to these services is subsidized by a government-funded program for individuals in the lowest income brackets (

10). While these facilities involve a referral network, patients can also seek secondary and tertiary care levels without a formal referral.

Regarding mental health care services, patients without social security benefits can seek care using a network of 38 psychiatric hospitals, only one of which is exclusively for children and adolescents. In the primary care level, care is offered in general health centers with psychological or psychiatric services as well as in mental health community centers.

Although public services allocate funds for treatment of some mental disorders (e.g., autism), which includes appointments with a medical specialist, diagnostic studies, and pharmacological treatment (

11), they do not cover neurodevelopmental interventions, which are considered a main line of treatment. Finally, the public education system offers a parallel network where parents of children with neurodevelopmental disorders can receive an informal diagnosis or intervention (

12). Family interactions with the health care and education systems also play a considerable role in age of diagnosis.

Studying pathways to diagnosis could help identify the points where the system fails to meet patients’ needs regarding diagnosis and referral because they may reflect a patient’s search for help outside of formal referrals. To understand diagnostic delays and their underlying causes, this study attempted to map the pathways in the health care system followed by Mexican families without social security that led to an ASD diagnosis.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

The sample was recruited from autism clinics of two specialized health centers: a psychiatric hospital for children and adolescents in Mexico City and a pediatric hospital in Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas. Both are tertiary care centers with medical residency programs, receive patients with no social security benefits, and are located in urban areas. The participants had been previously evaluated by psychologists and psychiatrists using the following standardized tools for a confirmatory diagnosis: Autism Diagnostic Interview–Revised, Autism Diagnostic Observational Scale–General (

13), Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule–Generic (

14), and Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia–ASD Supplement (

15).

Recruitment was performed between July 2015 and February 2016. Parents of children with a definitive diagnosis of ASD were approached in waiting rooms, where trained clinical psychologists invited them to participate in the study and interviewed them while their children were receiving therapy. The interview consisted of a comprehensive structured questionnaire to obtain a step-by-step description of the help-seeking pathway undertaken until the child received a formal diagnosis. The interview took 30 to 60 minutes, and the participation rate was 95% (N=186).

Assessment Tools

The Interview for Seeking Autism Resources in Children (I-SEARCH) is an interview developed by the authors (P.Z.R., L.A.G.). The interviewer asks for a list, in detailed chronological order, of the different professionals and places participants visited while looking for a diagnosis for their child. It inquires about sociodemographic data, age of the child when the parent first became concerned about his or her development, date of first consultation with a health care provider, sequence of professionals visited to reach a diagnosis of ASD, specialty of the health care professionals, age of the child at each evaluation, type of diagnosis, and any other relevant information given by the health care professional. Examples of questions in the I-SEARCH include, “Who was the first person you visited regarding the concerns you had about the development of your child?” “Did you decide to visit this person on your own?” and “Who recommended that you visit this person?”

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics summarizing the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample are presented as mean±SD, median and interquartile range (IQR), or frequency and percentage. Health care professionals were grouped as follows: mental health professionals, including psychiatrists, child psychiatrists, psychologists, and neurologists (N=464, 55%); pediatricians/neuropediatricians (N=204, 24%); primary care physicians (N=82, 10%); and “other” clinical professionals, including language and rehabilitation specialists (N=90, 11%).

We also obtained information about the following variables related to diagnostic delay (in months): time of first parental concerns, time of first medical appointment, child’s age at diagnosis, parent’s delay time (time between first parental concerns and first appointment), health care system’s delay (time between first appointment and age at diagnosis), and total delay time (time between the first parental concerns and the age at diagnosis).

To compare each of the delays by subtype of diagnosis (autism versus Asperger’s syndrome, according to

DSM-IV) we used a Mann-Whitney U test. Afterward, we performed a generalized linear model with Poisson error to explore the effect of sociodemographic and clinical variables. Predictor variables were simultaneously introduced into a single model without interaction terms. We evaluated the contribution of each variable by performing an analysis of variance on the results of the model and performed comparisons among clinical specialists by means of a post hoc Tukey test with the package multcomp, version 1.4 (

16). Finally, we performed a binomial logistic regression to evaluate the effect of the presence or absence of initial parental concerns on the total delay time by using the package nlme, version 3.1 (

17). Just as above, predictor variables were simultaneously introduced into the model without interaction terms. Statistical analysis and data visualization were performed by using R (

18). Significance for all tests was set at p<0.05, and analyses considered two tails.

Ethical Statement

The study was approved by the institutional review board of both health centers. Participants read and signed an informed consent form before starting the interview. Participation was voluntary, and respondents could terminate the interview at any point, knowing that withdrawing from the study would not affect the care they received at the hospital. A debriefing at the end of the interview was offered.

Results

Sociodemographic Description

The sample consisted of 186 interviewed participants, 46% (N=85) from the children’s psychiatric hospital and 54% (N=101) from the pediatric hospital). The mean age of children was 7.9±3.7 years, 88% were male, 70% had a diagnosis of autism, and 30% had a diagnosis of Asperger’s syndrome.

About half of the cases concerned the firstborn or only child (54%), a majority of families were biparental (67%), about half of interviewees had a high school education or less (53%), and slightly fewer had a bachelor’s degree (41%). Around three-quarters of the families (72%) had a monthly income of $323 (about 6,000 Mexican pesos) or less. A quarter of participants reported having another family member with ASD, aside from their child.

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the participating families.

Diagnostic Pathways

We identified a median diagnostic delay of 27 months (IQR 8–36) and a median of three professional contacts (IQR 3–6) to reach a diagnosis, with some patients requiring up to 11 contacts within the health system.

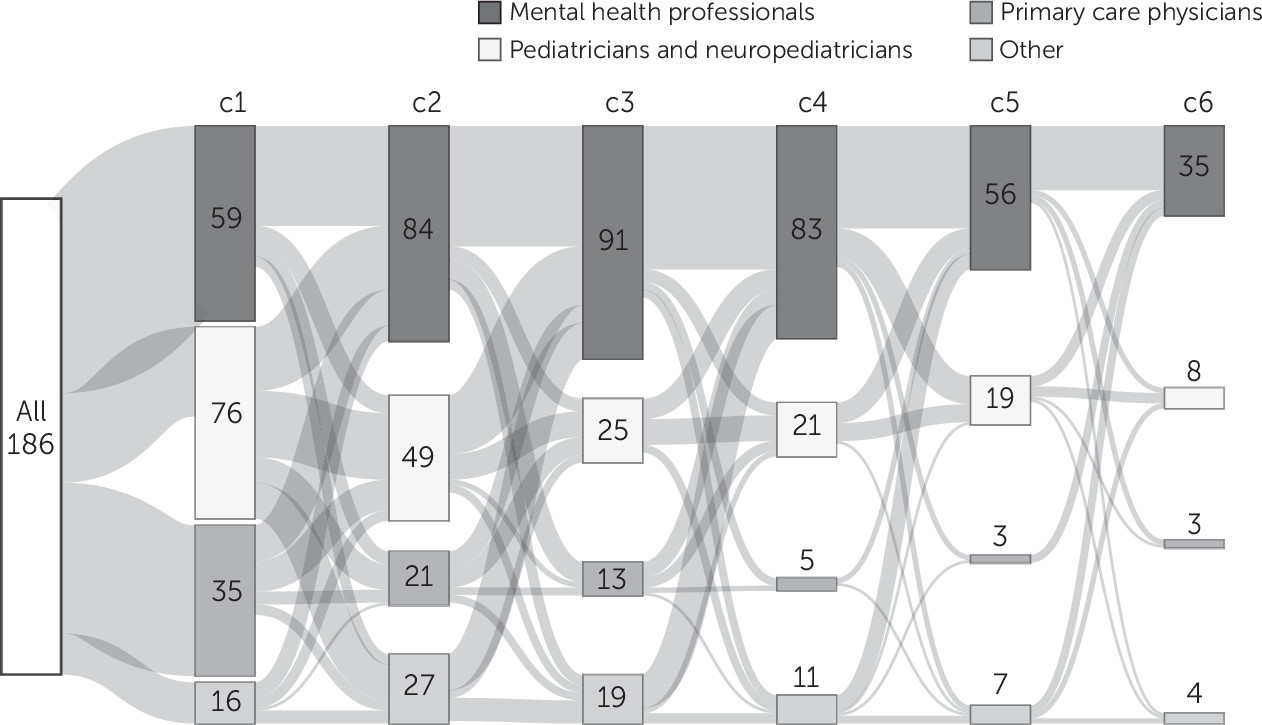

The Sankey plot (

Figure 1) shows the pathways of patients and the change in the types of health care professionals they visited at each contact. As shown in the timeline, the number of parents contacting mental health professionals increased, while the number of those approaching other clinical professionals decreased or stayed the same. (An interactive version of the plot is available at

https://tinyurl.com/y8pjfyue.)

Table 2 shows the number of patients at each contact (C), how many were seen by each type of clinical professional, how many received a diagnosis, and the time elapsed to diagnosis for the whole sample. Most families consulted pediatricians/neuropediatricians (41%) as their first contact, followed by mental health professionals (32%), while primary care physicians represented a smaller proportion (19%). However, as more clinicians were contacted, the percentage of patients seen by mental health professionals grew considerably, reaching 70% by the sixth contact. The number of patients with diagnoses peaked between C3 and C5; by the end of C5, 73% (N=136) of the sample had received an ASD diagnosis. Mental health professionals and pediatricians/neuropediatricians performed most of the diagnoses (78% [N=145] and 22% [N=41], respectively).

Diagnostic Delay Times

Table 3 summarizes the metrics for diagnostic delay. The median delay attributable to the health care system was three times larger than the median parental delay (18 versus 6 months). Additionally, we found that, compared with a diagnosis of autism, an Asperger’s syndrome diagnosis was associated with longer delays in each of the delay metrics, except for the time of first parental concerns. (Histograms of delay metrics can be found in an

online supplement.)

Sociodemographic Variables’ Influence on the Delay to Diagnosis

Regression analysis showed that sex and child’s age at first contact were positively associated with a longer diagnostic delay (

Table 4). Girls and older children received diagnoses later than boys and younger children. Variables associated with a shorter time to diagnosis included having another family member with ASD or suspecting the diagnosis of a family member and having consulted a mental health professional as a first contact (vs. pediatrician/neuropediatrician or other). An Asperger’s syndrome diagnosis (vs. autism) and larger family income (vs. lower income) were associated with a longer diagnostic delay. Neither the parent’s education level nor the type of clinical center visited affected the diagnostic delay. Finally, predictors of a shorter total diagnostic delay were parental concerns of social deficits, language, and developmental regression.

Discussion

In this study, we analyzed the pathways to diagnoses of ASD in the Mexican health care system. The diagnostic delay observed in the sample was within the range of that reported for other countries. Fortea et al. (

19) reported a mean delay of 13.6 months for patients in specialized centers in the Canary Islands, Spain (N=72), whereas Ribeiro et al. (

20) reported 36 months in a Brazilian clinical sample (N=19). However, studies looking at large community samples report longer delays: a 42-month delay (N=1,047) in the United Kingdom (

21), 30.1 months in the United States (N=969) (

4), 32 months in India (N=141) (

22), and 55.4 months in Germany (N=207) (

23). Similarities in the diagnostic delays among countries may reflect the difficulties intrinsic to an ASD diagnosis.

The method of our study allowed us to dig deeper into systemic factors by understanding families’ own accounts of their navigation within the health care system. We found that the pathway to diagnosis predominantly included visits to development and mental health professionals. Unexpectedly, patients often moved from tertiary (mental health professionals) to primary care (primary care physicians) even during the later stages of the pathway. Despite these shifts, the proportion of cases reviewed by mental health professionals increased over time, and practically all families had received a diagnosis by the 11th contact. Mental disorders were recognized (almost half of the patients were seen by mental health professionals by the second contact) but not specified; the percentage of patients diagnosed as having ASD at every contact was never above 18% of the total sample.

As in other studies (

4,

21,

24), pediatricians were the predominant health care professionals to serve as first contact. Most studies have focused on the reasons why pediatricians/neuropediatricians show a diagnostic delay (

25,

26). Some of these reasons might also apply to mental health professionals, such as the apprehensiveness to grant a definitive diagnosis before the achievement of developmental milestones, or “passing the buck” (

27); lack of proper diagnostic tools (

28,

29); and the absence of multidisciplinary teams (

30). Specifically, the findings of our study could reflect a lack of diagnostic tools used by first medical contacts as well as professionals’ lack of knowledge about protocols or clinical guides to consult for possible cases of ASD. For instance, in Mexico, developmental milestone guidelines (

31) do not include an algorithm to help clinicians decide when a screening for autism is necessary. These factors may influence parents whose child is under pediatric or psychiatric hospital care to keep looking for a diagnosis in primary care centers without a formal referral. It is worth noting that most visits to new health care professionals seen in the pathway do not reflect referrals but patients’ own attempts to look for help. Patients who seek care without a referral face increased risk of having longer diagnostic delays compared with the median reported.

Sociodemographic variables also had an impact on diagnostic delays. The presence of a relative with ASD, or suspected to have ASD, reduced delay times, which is to be expected because previous experience makes families more aware of symptoms or the appropriate venue and professional to visit (

32). In contrast with other studies (

4), we found that a higher income increased delay time. Families with more resources may seek more contacts in search of a second opinion. We found longer diagnostic delays for girls compared with boys, similar to previous reports (

33,

34). These reports also found longer diagnostic delay for patients showing less cognitive impairment, which makes ASD symptomatology less obvious to clinicians. A highly replicated finding (

8) was that children with Asperger’s syndrome were older when parents had their first concerns, had longer delays in seeking professional help, and took longer to receive a diagnosis than those with autism. This circumstance is usually explained by the fact that children with Asperger’s syndrome display better adaptive skills and milder symptoms and are often not grouped with children with intellectual disabilities and thus may go unnoticed. Finally, regarding the role of the family in initiating the search for help within the health care system, we observed that families that had concerns related to language delay, developmental regression, and poor social interaction had shorter diagnostic delays in comparison with families that did not have such concerns, as has been previously reported (

35,

36). This outcome could occur because these issues are suggestive of severe symptomatology.

Recommendations

Because the largest factor of delay seems to be related to the health care system (median=18 months) (

Table 3), we propose the following recommendations: train primary physicians and develop broad screening tools regarding the main symptoms of ASD (i.e., red flags), establish routine screening with Mexican standardized tools among children younger than 2 years, strengthen cross-communication between child psychiatrists and pediatricians so that joint vigilance of unclear cases can continue until a consensus is reached, raise awareness among families (using leaflets or other media available in waiting rooms) regarding the benefits of working within the health care system’s organizational flow, consider using a mixed model (both medical and educational) where therapeutic interventions also can be provided in school scenarios, and combat the stigmas associated with ASD so that doctors are not apprehensive about diagnosing.

Strengths and Limitations

Our results should be interpreted in light of the following limitations. The interview may be influenced by recall bias. However, parents had access to their medical appointment cards to validate exact times of clinical appointments and the type of medical professional consulted. We recruited patients at a tertiary level of care, including patients with particularly severe symptoms, and therefore our results may not be extrapolated to a general population, in which delays could be longer. A direction for future work could focus on the pathways of patients in community samples. Finally, we did not have access to measures indicative of the intellectual quotient of the patients.

Regarding the strengths, our study provides one of the first descriptions of clinical pathways of ASD in Latin America, a region for which there is little information available. Also, although this study included fewer patients compared with other studies (

4,

21), the face-to-face interviews using the I-SEARCH method allowed us to reconstruct pathways with a high level of detail. Finally, this study is the first that reports the health care system’s diagnostic delay separately from the total delay time.

Conclusions

Diagnostic delay for ASD in the Mexican health care system appears to be associated with systemic factors, such as failure to identify symptoms early, lack of coordination between professionals, and weaknesses in the referral and counter-referral systems in public health care institutions. Clinical and sociodemographic variables influence delay in a manner consistent with previous studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the patients and families whose generous contributions made this study possible. They are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their comments and thank Dr. Carolyn O’Meara for translating this article into English.