Individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders are more likely to smoke tobacco, smoke heavily (

1), and have severe dependence compared with those without psychiatric illness (

2–

4). Smoking rates are not decreasing for those with schizophrenia, as they are in the general population (

5), and smoking-related disease contributes disproportionately to a comparative 29-year mortality gap among adults (

6–

9). Although quitting smoking by middle age reduces the risk of death associated with continued smoking by 90% (

10), smokers with schizophrenia are less likely than those in the general population to be offered effective pharmacotherapeutic smoking cessation aids, particularly varenicline (

1,

11,

12). Consistent reports of abstinence rates of less than 5% among smokers with schizophrenia who receive behavioral smoking cessation treatment alone (

13–

19) suggest that this group in particular needs pharmacotherapeutic cessation aids to quit smoking.

Despite evidence of the safety and efficacy of first-line pharmacotherapeutic cessation aids in this population (

19,

20), clinicians report negative attitudes toward providing smoking cessation treatment for smokers with schizophrenia (

21), and pharmacotherapy—particularly nonnicotine pharmacotherapy—is particularly underutilized (

1,

11,

12,

22,

23). Additionally, Medicaid coverage of the most effective cessation treatments remains limited in many states, despite legislation barring state Medicaid programs from excluding cessation medications approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) from coverage (

24). High copays and prior authorization requirements remain common barriers to obtaining smoking cessation medication through Medicaid and Medicare plans that insure most people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders (

25). Additionally, limits on access to effective smoking cessation treatment, through low rates of prescribing and financial barriers, place people with schizophrenia at increased risk of smoking-related disease and death.

The neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy trial of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) among smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (Evaluating Adverse Events in a Global Smoking Cessation Study [EAGLES]) estimated the incidence of moderate to severe neuropsychiatric adverse events (NPSAEs) during a 12-week treatment period and 12-week follow-up and assessed tobacco abstinence rates (

26). NPSAE incidence and continuous abstinence rates have been reported for the schizophrenia spectrum disorders subcohort and compared with rates for the mood and anxiety disorders subcohorts (

27). To address safety concerns that may drive the particular underuse of effective smoking cessation medications for smokers with schizophrenia, we undertook a post hoc analysis of weekly patterns of NPSAEs and abstinence rates in the EAGLES schizophrenia spectrum disorders subcohort compared with smokers without psychiatric disorders. Our approach included analysis of timing of NPSAEs relative to start of study medication and change in weekly 7-day point prevalence abstinence (PPA) status and analysis of end-of-treatment abstinence rates by baseline psychiatric symptom severity rating.

Methods

EAGLES was a multinational, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active (NRT)-controlled trial, conducted from November 30, 2011, to January 13, 2015. The primary report provides details of the design and primary outcomes (

26). Study procedures and consent forms were approved by the institutional review boards at participating institutions. All participants signed informed consent.

Eligible participants were adults motivated to quit smoking, ages 18–75 years, who smoked 10 or more cigarettes per day, with expired carbon monoxide (CO) >10 parts per million (ppm) at screening. Eligible smokers with schizophrenia spectrum disorders met

DSM-IV-TR (

28) diagnostic criteria for current or lifetime psychotic disorders, including schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders. Smokers with schizophrenia spectrum disorders who had other psychiatric comorbid conditions were not excluded, except for those with an alcohol or other drug use disorder active within the previous 12 months. Smokers with schizophrenia spectrum disorders made up approximately 10% of the psychiatric cohort (N=390) in EAGLES. Enrollment criteria required a score of <5 on the 7-point Clinical Global Impression–Severity (CGI-S) (

29), indicating moderate severity of symptoms or less. The control cohort without psychiatric disorders (N=4,028) had no axis I diagnosis.

Random Assignment, Masking, and Study Treatment

Random assignment to receive 1 mg varenicline twice daily, 150 mg bupropion sustained-release twice daily, 21 mg NRT transdermal patch per day with taper, or placebo was done in a 1:1:1:1 ratio, with block size of eight for each diagnostic subcohort by region in a double-blind, triple-dummy, parallel-group design. Participants set a target quit date 1 week after random assignment, coinciding with the end of varenicline and bupropion up-titration and initiation of NRT. Study visits were weekly for 6 weeks, biweekly for 6 weeks, and then at weeks 13, 16, 20, and 24. Ten-minute individual smoking cessation counseling was provided at each visit (

30). Telephone contacts to determine smoking status were conducted weekly between visits.

Assessments

Psychiatric diagnosis was assessed at screening with the Structured Clinical Interviews for DSM-IV-TR Axis I and II Disorders (SCID-I and SCID-II) (

28,

31). Severity of cigarette dependence was assessed with the Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence (FTCD) (

32). Abstinence was assessed weekly and defined as self-report of tobacco abstinence since the previous study assessment. Expired CO of ≤10 ppm was used to validate self-reported abstinence. CO was collected at study weeks 1–6, 8, 10, 12, 16, and 24. Participants who discontinued the study or were lost to follow-up or had missing CO data at weeks 12 or 24 were considered nonabstinent.

An NPSAE was an adverse event in one of 16 neuropsychiatric symptom categories voluntarily reported, observed, or solicited via questioning during treatment or 30-day follow-up that was new or increased in severity from baseline, irrespective of whether the adverse event was considered causally related to study medication, and that met a priori severity criteria. The following events met criteria for an NPSAE: those expected to be more common (anxiety, depression, feeling abnormal, or hostility) that were rated as severe and those rated as moderate or severe in the categories of agitation, aggression, delusions, hallucinations, homicidal ideation, mania, panic, paranoia, psychosis, suicidal ideation, suicidal behavior, or suicide.

NPSAEs were assessed at each study visit with open-ended questions, direct observation, and the semistructured Neuropsychiatric Adverse Event Interview (

26,

33), which encompasses and extends beyond the psychiatric adverse events captured in the

Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities. Positive responses on the Neuropsychiatric Adverse Event Interview were evaluated for frequency, duration, and severity to determine whether they qualified as NPSAEs. Investigators evaluated whether positive responses on the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) or proxy reports from family members or others qualified as NPSAEs. Psychiatric symptoms were assessed at each study visit with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (

34) and C-SSRS (

35). Tobacco and nicotine use were assessed with a structured questionnaire and expired CO measurement.

Analysis

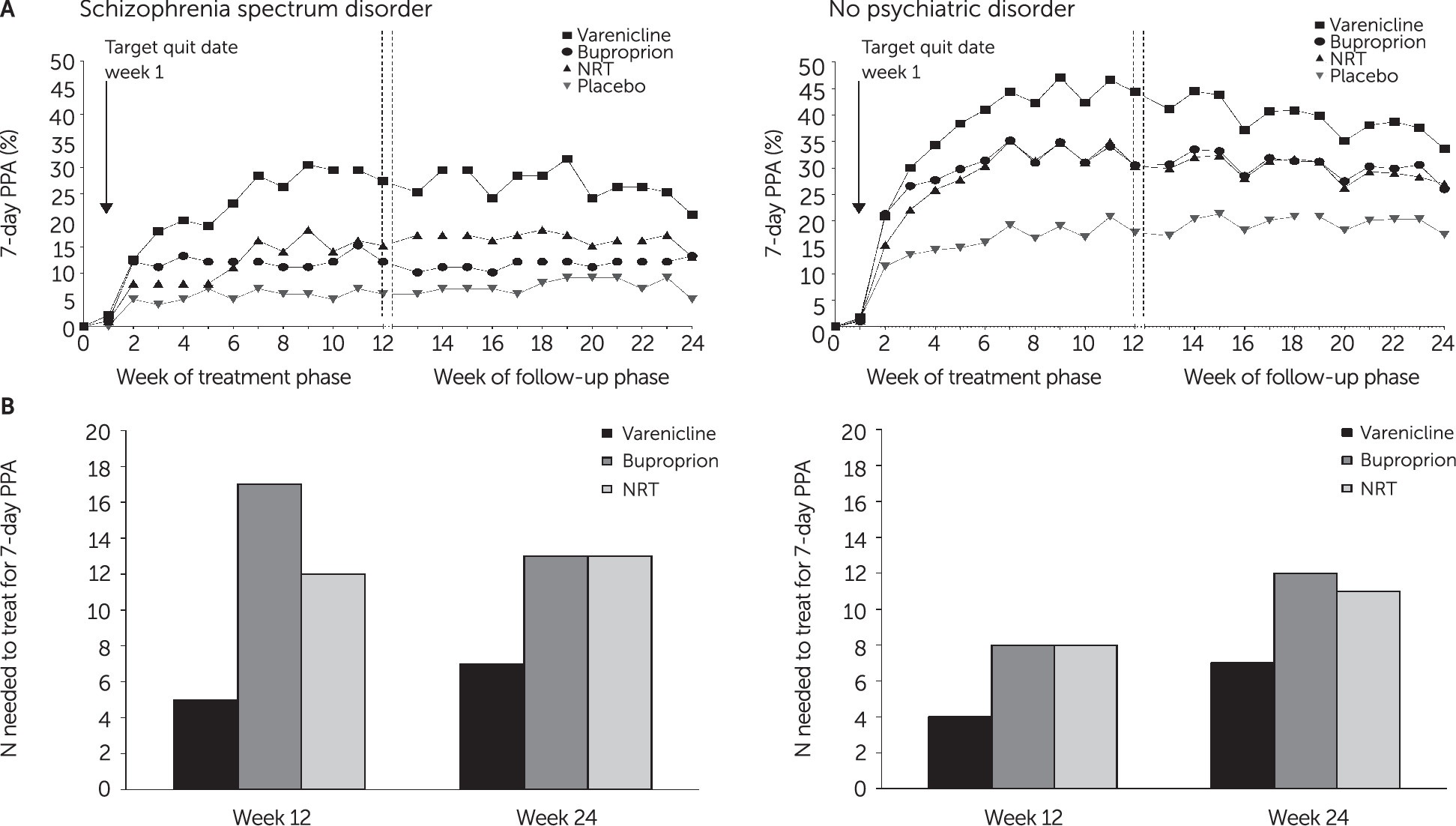

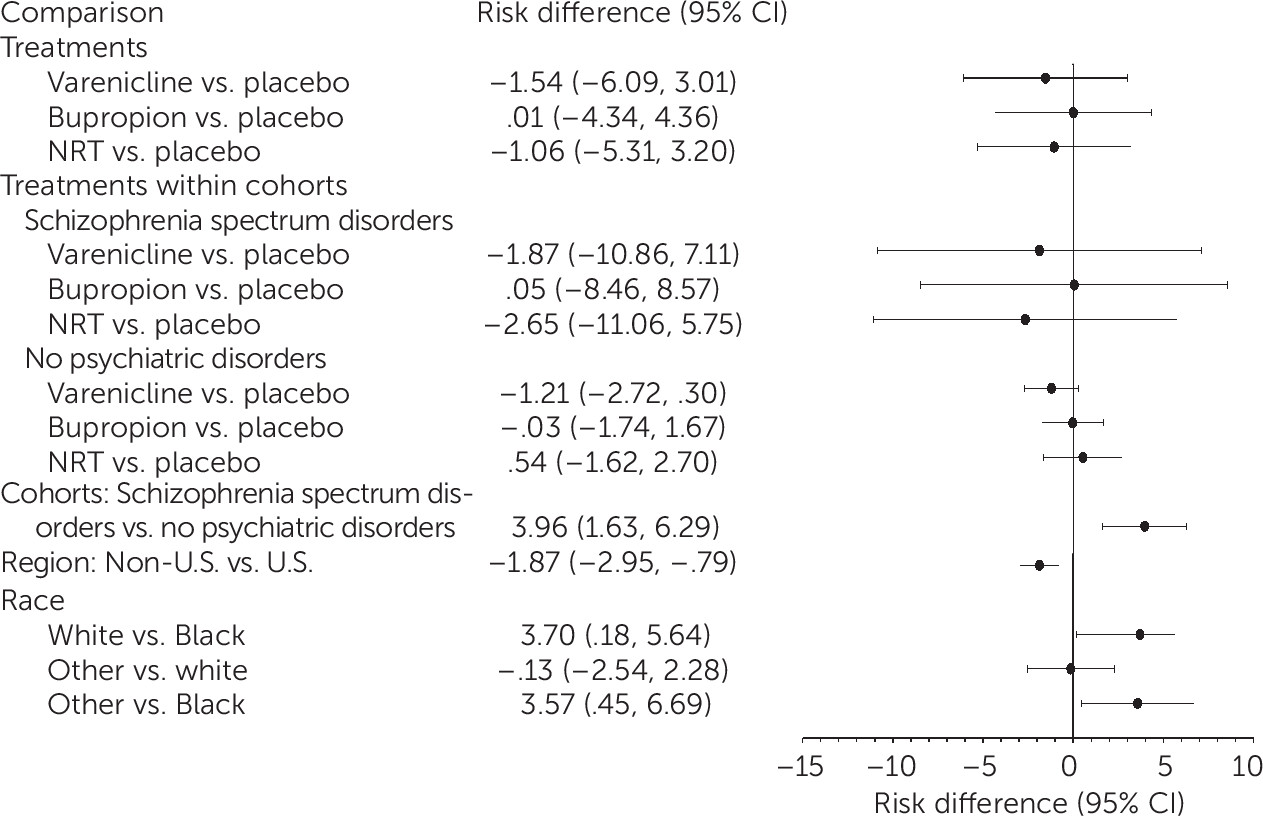

Generalized linear models (GLMs) were conducted to test the effect of treatment (varenicline, bupropion, NRT, or placebo) and cohort (schizophrenia spectrum disorders or no psychiatric disorders) on 7-day PPA and continuous abstinence rates during the treatment and follow-up periods. Observed rates of NPSAEs were reported, and GLMs were conducted to test effects of treatment, cohort, and their interaction on the NPSAE primary endpoint for 16 weeks following treatment initiation (12 weeks of treatment and 4 weeks of follow-up). All models included region, age, race, body mass index (BMI), smoking characteristics, and past cessation medication use if associated with outcome (

36). For each reported NPSAE, the week of the event was plotted together with change in weekly 7-day PPA status—smoker, partial abstainer, and abstainer—by treatment assignment and cohort.

Discussion

This analysis provides robust evidence for efficacy of first-line FDA-approved smoking cessation medications—particularly varenicline—among smokers with schizophrenia spectrum disorders and those without psychiatric disorders. The NNT to obtain end-of-treatment abstinence were 5 and 4, respectively, with no clear relationship in either cohort between baseline psychiatric symptom burden and attainment of abstinence or between the occurrence of NPSAEs and treatment. In both cohorts, odds of 7-day end-of-treatment PPA were higher with varenicline than with bupropion, NRT, or placebo and higher with NRT than with placebo. Prior trials have shown efficacy of varenicline (

37), bupropion (

14,

15), and bupropion combined with NRT for smoking cessation among smokers with schizophrenia (

16,

17). EAGLES is the first trial to report efficacy of NRT versus placebo for smoking cessation among smokers with schizophrenia.

Because of the greater severity of nicotine dependence and psychiatric symptom burden among smokers with schizophrenia, these participants would be expected to be less likely to quit smoking, compared with smokers without an axis I psychiatric illness. Of note, we found no clear relationship among smokers with schizophrenia between abstinence rates and psychiatric symptom severity, and the NNT for varenicline among smokers with schizophrenia and those without psychiatric disorders was essentially equivalent (5 versus 4). Although the confidence intervals overlapped, point estimates for odds of abstinence with varenicline were nearly twice as high among smokers with schizophrenia as among smokers in the group without psychiatric disorders, which was likely attributable to very low abstinence rates for smokers with schizophrenia treated with placebo, which is consistent with prior reports of 4%−5% abstinence rates with behavioral treatment alone (

14–

16,

19,

37). Such low success rates indicate that it is critical for smokers with schizophrenia to have access to pharmacotherapeutic cessation aids if they are to be successful in their efforts to quit smoking. Varenicline is underutilized for smokers with psychotic illness (

11,

12), and in this trial, smokers with schizophrenia reported significantly fewer prior treatment trials with varenicline, bupropion, or NRT, compared with smokers without psychiatric disorders—without significantly fewer prior cessation attempts.

It is not surprising that smokers in the schizophrenia cohort were more likely than those in the control group to experience an NPSAE during the treatment and follow-up periods, given their greater psychiatric symptom burden; higher ratings of anxiety, depression, aggression, and nicotine dependence severity; and more prior suicidal ideation and behavior. The baseline NPSAE rate for smokers with schizophrenia outside the context of a smoking cessation attempt was unknown. For smokers with schizophrenia, NPSAEs appeared to be multifactorial and sporadic: they did not cluster either within any particular symptom domain or shortly after study medication was initiated or the quit date; they occurred independently of treatment assignment; they rarely led to permanent discontinuation of smoking cessation medication; and approximately one-third were reported during study weeks with partial or complete tobacco abstinence. Serious adverse events were observed for less than 0.5% of smokers in the schizophrenia subcohort and for 0.2% of those in the cohort without psychiatric disorders. These findings are worth weighing against the well-established metric that half of smokers who do not quit will die prematurely from a smoking-related illness.

It is now considered a standard of care to offer effective smoking cessation pharmacotherapy to all smokers at every clinical visit (

38), even for smokers who report that they may not be ready to make a cessation attempt. In considering the risk-benefit ratio of providing smoking cessation treatment to smokers with schizophrenia, several points are worth considering. It is increasingly recognized that smoking cessation itself does not significantly exacerbate the symptoms or course of mental illness (

39,

40) and that active treatments that significantly improve abstinence rates among smokers with schizophrenia do not exacerbate psychiatric symptoms (

19,

41). In EAGLES, smokers with schizophrenia treated with placebo and behavioral support were as likely as those treated with varenicline, bupropion, or NRT to experience a moderate to severe NPSAE but were far less likely to attain abstinence. The life expectancy for people with schizophrenia is approximately 29 years shorter than for those without psychiatric illness, and tobacco smoking is the single largest cause of this disparity in life expectancy (

8,

42,

43), whereas smoking cessation effectively mitigates this risk (

10,

44,

45). Because tobacco smoking is associated with increased hepatic clearance of many psychotropic drugs, particularly those metabolized by cytochromes P450 1A2 and 2E1, it is recommended that clinicians monitor patients who reduce or quit smoking for evidence of reduced clearance of psychotropic medications metabolized by these enzymes and consider dose adjustment accordingly (

46–

48).

The study had several limitations. Although 27% of smokers with schizophrenia had a prior alcohol or drug use disorder, smokers with an active alcohol or drug use disorder other than nicotine were excluded, so results cannot be expected to generalize to those with active substance use. Likewise, although participants were symptomatic at baseline, enrollment criteria required that psychiatric symptoms be stable, and 95% of smokers with schizophrenia were taking psychotropic medications. Thus, results cannot be expected to generalize to unstable or untreated smokers with schizophrenia. Although increasingly considered standard clinical care, dual NRT (NRT patch plus NRT gum, lozenge, nasal spray, or inhaler) was not tested. Future research is needed to test the effects of dual NRT for smokers with schizophrenia and to compare efficacy and tolerability of dual NRT with those of varenicline and bupropion. The behavioral component of the intervention was brief; trials of pharmacotherapy plus more intensive behavioral treatment have shown higher abstinence rates among smokers with schizophrenia (

49). Further research is needed to determine whether more intensive behavioral treatment improves efficacy of pharmacotherapy for nicotine dependence among smokers with schizophrenia. We reported 24 weeks of efficacy data and 16 weeks of safety data, although clinicians and smokers will be interested in longer-term outcomes (

49,

50).