The Affordable Care Act (ACA) aimed to increase access to health care by expanding Medicaid coverage to low-income adults without children and by subsidizing premiums for private insurance plans purchased on exchanges. Because individuals with mental health problems are overrepresented among low-income population groups, commentators predicted that implementation of ACA provisions would especially benefit these individuals (

1–

4).

Results from the first 2 years after implementation of the ACA indicated significant increases in Medicaid and corresponding reductions in the numbers of uninsured individuals among low-income adults overall (

5,

6). These changes were also associated with reductions in reported financial barriers to health care. The proportion of low-income adults who reported that they did not receive needed medical care because of their inability to afford it was significantly reduced in Medicaid expansion states. However, there were parallel increases in structural barriers, such as less availability of timely appointments and increased wait times (

5). No appreciable change in the use of medical services was reported (

5).

These analyses were limited to general medical service use. The results may be different for mental health care because the ACA included several provisions to counter insurance disparities between mental and general health care, enhance care coordination, and improve financing of mental health services (

4). As a result, observers predicted increases in availability and use of mental health services after implementation of the ACA, especially among low-income adults (

4). Additionally, the higher price elasticity of demand for some mental health services compared with general health services (

7) suggested that improved financial access to mental health care would be associated with a higher proportional increase in the use of these services compared with general health services.

However, analyses of the first 2 years after ACA implementation failed to identify any significant changes in the prevalence of mental health treatment, although significant reductions in uninsurance rates were noted (

8). The longer-term effects of the ACA on mental health service use and on barriers to mental health care remain unexplored. This report used data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) for 2009–2018 to examine changes in insurance coverage; mental health service use; perceived unmet need for care; and financial, attitudinal, and structural barriers in the years before and after ACA implementation.

Methods

The NSDUH survey methods have been described elsewhere (

9). In brief, NSDUH is a national household survey conducted annually by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration through face-to-face interviews with adults and adolescents. This study focused on individuals ages 18 and older. A stratified, multistage area probability sampling design was used. Census tracts, census block groups, segments within census block groups, and dwelling units within segments were selected with probability proportional to sample size. An interviewer visited each dwelling unit to obtain a roster of household residents. Up to two residents who were ages 12 or older were selected for interviews on the basis of this roster. Persons without an address (e.g., homeless persons not in shelters), active duty military personnel, and institutional residents were not included. The weighted NSDUH sample is representative of the U.S. general population. The NSDUH data collection protocol was approved by the institutional review board at RTI International.

The interview response rates, according to the definition from the American Association for Public Opinion Research (

10), ranged from 75.6% in 2009 to 66.6% in 2018 (median=71.5%). The public access data set used in this study included data on 404,489 adult participants (ages 18 or older) across the 2009–2018 surveys. Of these participants, 78,874 (14.2%) were categorized as low-income adults (i.e., family income <100% federal poverty level). The study sample was further limited to 15,968 (18.0% of the low-income adults) individuals who met the criteria for serious psychological distress described below.

Serious psychological distress was defined by a score of 13 or higher on the Kessler Screening Scale for Psychological Distress (K6), a validated six-item measure of psychological distress commonly used in general population surveys. Health insurance was ascertained by asking about current coverage by Medicaid, Medicare, employer-sponsored or individually purchased private insurance, and other types of health insurance (e.g., veterans’ health insurance, TRICARE). Mental health service use was assessed with questions about outpatient or inpatient treatment for problems with “emotions, nerves, or mental health” or about using medication that was prescribed “to treat a mental or emotional condition” in the past 12 months.

Perceived unmet need for mental health care and barriers to care were ascertained by first asking, “During the past 12 months, was there any time when you needed mental health treatment or counseling for yourself but didn’t get it?” Participants who responded affirmatively were next asked about the reasons for not receiving such care. For this study, the responses were categorized into financial, attitudinal, and structural barriers. Financial barriers included not being able to afford the cost, health insurance not covering any mental health treatment or counseling, or health insurance not paying enough for treatment or counseling. Attitudinal barriers included concerns that getting mental health treatment or counseling might cause neighbors or community members to have a negative opinion of the participant, concerns that getting treatment or counseling might have a negative effect on their job, concerns about confidentiality, not wanting others to find out that the person needed treatment, fears of being committed to a psychiatric hospital or forced to take medicine, beliefs that treatment is not needed at the time, and beliefs that the person could handle the problem without treatment or that treatment would not be helpful. Structural barriers included not knowing where to get services, not having time (because of job, child care, or other commitments), not having transportation, being too far from treatment, and inconvenient service hours.

Analyses were conducted in three stages. In the first stage, sociodemographic characteristics, insurance status, and mental health service use among low-income adults with psychological distress were compared between the 2009–2013 (N=7,834) and 2014–2018 (N=8,134) periods. In the second stage, unmet need for mental health care was compared between these periods. Comparison of perceived unmet need was limited to 9,351 low-income adults with psychological distress who had not received any mental health care in the past year (2009–2013, N=4,772; 2014–2018, N=4,579). In the third stage, specific barriers to mental health care were compared between the two periods. Barriers were examined among 2,057 low-income participants with psychological distress who had not received any mental health care and who reported perceiving unmet need for mental health care (2009–2013, N=1,069; 2014–2018, N=988).

Analyses were conducted with binary logistic regression models adjusted for age (18–25, 26–34, 35–49, ≥50), sex, race-ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, other), and urbanicity of residence (large metropolitan area, small metropolitan area, nonmetropolitan area). The svy routines of Stata, version 16.1, were used in all analyses to adjust the percentages and regression results for survey weights, clustering, and stratification on the basis of the Taylor linearization method. All percentages reported were weighted to make the estimates representative of the U.S. general population. Weighted percentages may differ from percentages based on unweighted data. Because data were pooled for each of the 5-year periods (2009–2013 and 2014–2018), to provide average estimates, annual survey weights were divided by five.

Results

The prevalence of psychological distress did not appreciably change between the two periods (2009–2013, 18.1%, N=7,834; 2014–2018, 17.9%, N=8,134; adjusted odds ratio [AOR]=1.02, 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.95–1.08, p=0.626). (The sociodemographic characteristics, health insurance information, and mental health service use of low-income adults with psychological distress in the two periods are in the online supplement.)

Few statistically significant differences were observed in sociodemographic characteristics of participants between the two periods. In both periods, a majority of participants were female (2009–2013, 65.6%; 2014–2018, 66.0%; AOR=0.98, 95% CI=0.88–1.09, p=0.692) and non-Hispanic White (2009–2013, 53.9%; 2014–2018, 53.7%; AOR=1.01, 95% CI=0.91–1.12, p=0.852). The proportion of participants from the “other” racial-ethnic group was modestly higher in the later period (2009–2013, 6.7%; 2014–2018, 8.1%; AOR=1.21, 95% CI=1.00–1.47, p=0.047). About half of the participants in both periods were in the age groups younger than 35 years. The proportion of participants ages 35–49 was somewhat lower in the later period compared with the earlier period (2009–2013, 26.3%; 2014–2018, 23.8%; AOR=0.88, 95% CI=0.80–0.97, p=0.013) (see online supplement).

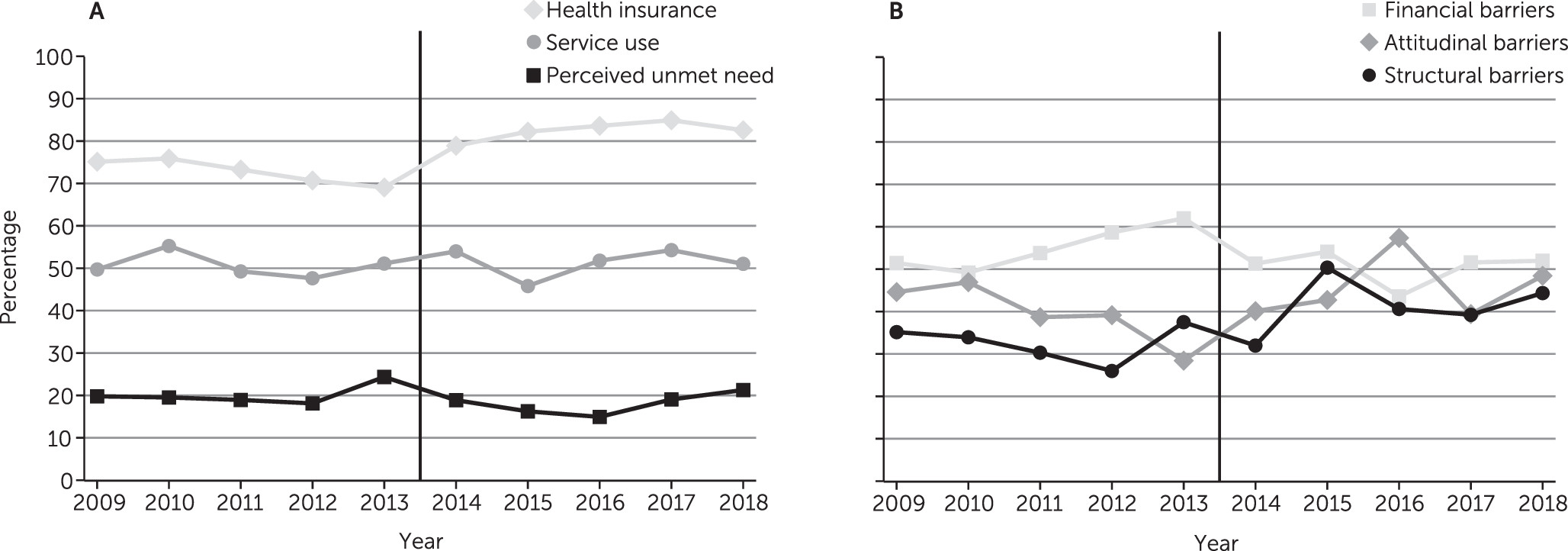

Medicaid coverage increased significantly in the period following implementation of the ACA (2009–2013, 43.9%; 2014–2018, 52.6%; AOR=1.48, 95% CI=1.32–1.65, p<0.001) as did private health insurance coverage (2009–2013, 18.0%; 2014–2018, 21.9%; AOR=1.25, 95% CI=1.09–1.42, p=0.001). Overall, any type of health insurance coverage increased significantly (2009–2013, 70.9%; 2014–2018, 81.5%; AOR=1.81, 95% CI=1.61–2.04, p<0.001) (see

online supplement and

Figure 1A).

Between 2009 and 2018, each year, 46% of low-income adults with serious psychological distress received any type of mental health care. This rate did not change significantly over time (2009–2013, 45.6%; 2014–2018, 46.4%; AOR=1.04, 95% CI=0.92–1.18, p=0.609). However, perceived unmet need for mental health care among low-income adults with psychological distress who had not received any mental health care modestly declined (2009–2013, 21.6%; 2014–2018, 19.2%; AOR=0.87, 95% CI=0.76–1.00, p=0.045) (

Figure 1A).

Analyses of barriers to receiving needed mental health care in the past year were assessed in the subsample of low-income adults with psychological distress who had not used mental health services and who perceived unmet need for mental health care in the past 12 months (2009–2013, N=1,069; 2014–2018, N=988). (For the results of these comparisons, see the

online supplement.) Not being able to afford the cost of mental health care was the most commonly reported barrier in both periods, with no significant change over time (2009–2013, 52.4%; 2014–2018, 46.6%; AOR=0.79, 95% CI=0.59–1.06, p=0.120). Financial barriers, overall, were the most common group of barriers to receiving mental health care in both periods, also with no significant change over time (2009–2013, 56.3%; 2014–2018, 51.3%; AOR=0.82, 95% CI=0.61–1.10, p=0.177) (

Figure 1B). Surprisingly, a larger proportion of participants in 2014–2018 compared with 2009–2013 reported that their health insurance plan did not cover any mental health treatment and counseling (2009–2013, 3.6%; 2014–2018, 6.1%; AOR=1.75, 95% CI=1.11–2.77, p=0.017).

In contrast to financial barriers overall, attitudinal barriers overall increased significantly across the two periods (2009–2013, 37.9%; 2014–2018, 44.7%; AOR=1.35, 95% CI=1.03–1.77, p=0.031), as did structural barriers (2009–2013, 32.6%; 2014–2018, 41.3%; AOR=1.46, 95% CI=1.11–1.92, p=0.006) (

Figure 1B).

The change in attitudinal barriers was driven by significant increases in the proportion of participants who avoided mental health treatment because of the fear of being committed against their will (2009–2013, 11.1%; 2014–2018, 16.1%; AOR=1.55, 95% CI=1.09–2.20, p=0.015) or the belief that treatment would not be helpful (2009–2013, 4.2%; 2014–2018, 6.6%; AOR=1.64, 95% CI=1.10–2.46, p=0.017). Among structural barriers, the increase was significant for not knowing where to receive treatment (2009–2013, 24.0%; 2014–2018, 31.2%; AOR=1.45, 95% CI=1.09–1.94, p=0.012) and for not having time (2009–2013, 8.1%; 2014–2018, 11.4%; AOR=1.48, 95% CI=1.07–2.05, p=0.017) (see online supplement). The proportion of participants who reported more than one barrier (based on the count of individual barriers) also increased significantly (2009–2013, 28.3%; 2014–2018, 38.9%; AOR=1.65, 95% CI=1.24–2.20, p=0.001).

Discussion

Consistent with past research (

8), the findings of this study suggest gains in insurance coverage for low-income adults with mental health problems after implementation of the ACA. However, these changes were not associated with significant increases in mental health service use and only a modest decrease in overall perceived unmet need for mental health care. Despite gains in health insurance coverage, the long-standing financial barriers to mental health care for low-income adults persist. Many individuals in need of mental health care continue to report being unable to afford the cost of such care. Furthermore, some attitudinal and structural barriers to mental health care have increased over the past decade.

It is difficult to know how the financial barriers to mental health care would have been affected in this period in the absence of the ACA. Research from the years preceding implementation of the ACA suggested an increasing trend in financial barriers to mental health care over time (

11,

12), a trend that might have continued in the absence of the ACA. Nevertheless, the findings highlight the need for further efforts to counter the persisting financial, attitudinal, and structural barriers to mental health care among low-income adults.

The findings of this study should be viewed in the context of the study’s limitations. First, the assessments were based on self-reports and, as such, were open to memory and social desirability bias. Second, other contextual factors besides ACA implementation may have contributed to the noted trends. For example, the period covered coincided with increasingly negative news coverage of mental illness, which may have contributed to negative attitudes toward mental health treatment seeking. Third, ACA implementation varied across the country as some states opted out of Medicaid expansion, and coverage of specific services varied across states. As such, this study provides a nationwide overview of trends in mental health service use and barriers to mental health care. Future studies need to examine trends separately for expansion and nonexpansion states.

Conclusions

In the context of these limitations, the study provides an overall picture of changes in service use and barriers to mental health care among low-income adults. Countering the multiple barriers that these vulnerable individuals face calls for a multipronged approach. Expansion of new technologies, such as telehealth and mobile interventions, provides opportunities to reduce structural barriers (

13). These advances, along with greater use of patient-centered approaches to mental health care (

14), can also affect public attitudes toward mental health treatment seeking. Furthermore, strengthening provisions for coverage of mental health services as part of the essential health benefits package under the ACA can improve financial access to these services (

15). Meaningful improvements in access to mental health care in future years depend on the success of these and other initiatives to effectively counter the various barriers that many low-income individuals with serious mental health problems face.