To improve early identification, treatment, and prevention of HIV, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) revised its HIV testing recommendations in 2006 to include routine HIV testing for all patients between the ages of 13 and 64, marking a shift away from risk-based testing (

1). In 2013, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) also recommended routine HIV testing for patients ages 15–64 (

2). This recommendation was important, because USPSTF guidelines have implications for reimbursement. Unfortunately, these recommendations have not been consistently implemented across health care settings. Physicians often cite insufficient time, stigma, consent burden, competing priorities, and reimbursement concerns as barriers to HIV testing (

3).

These facilities may play an especially important role in diagnosing HIV among the 25% of people with serious mental illness who have comorbid substance use disorders (

6), nearly 30% of whom seek substance use treatment services (

6). People with serious mental illness are up to 10 times as likely as the general U.S. population to have HIV (

7), and people living with HIV and serious mental illness are more likely to experience increased HIV-related morbidity and mortality from decreased receipt of antiretroviral treatment and lower rates of viral suppression (

8–

10). Despite this high prevalence and poorer HIV treatment outcomes, HIV testing in this population remains quite low (

11).

Results

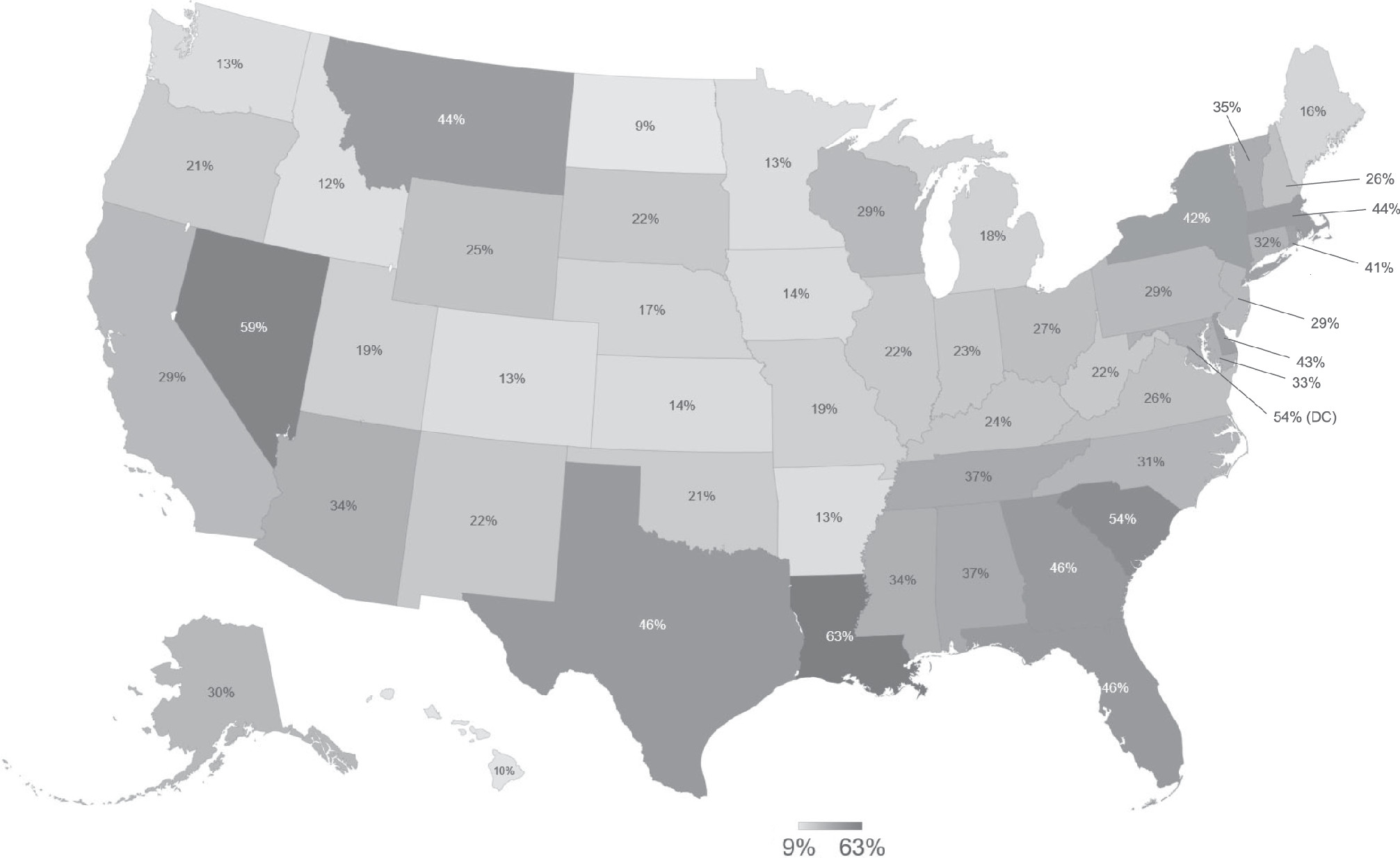

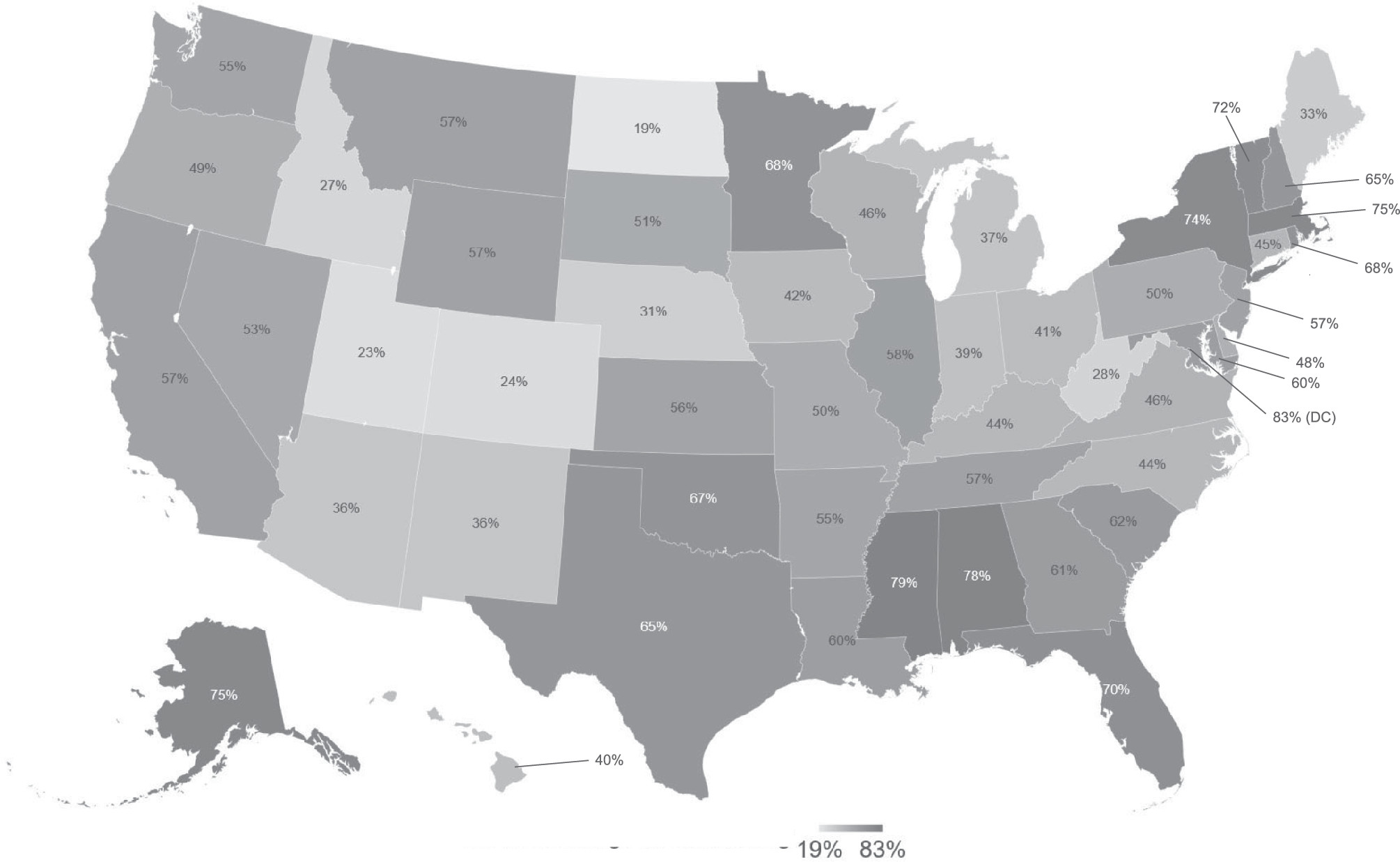

As shown in

Table 1, of the 14,691 facilities, 29.0% offered HIV testing, 53.0% offered HIV counseling, 23.4% offered both HIV testing and counseling, and 41.4% offered neither. We found significant state-to-state variation in the proportion of facilities offering HIV testing (range 9.0% to 62.8%) (

Figure 1) and HIV counseling (range 19.2% to 83.3%) (

Figure 2). (A table in an

online supplement to this article provides state-specific details.)

Among facilities that provided medication for opioid use disorder, 48.0% offered HIV testing, 64.2% offered HIV counseling, 38.4% offered both, and 26.3% offered neither (

Table 1). Rates of HIV testing availability were significantly higher in facilities offering medication for opioid use disorder, compared with those not offering such medication (48.0% versus 16.0%), with an adjusted estimate of the difference in testing rates of 30.8% (p<0.001). HIV counseling was significantly higher in facilities offering medication for opioid use disorder, compared with those not offering such medications (64.2% versus 45.4%), with an adjusted estimate of the difference in counseling rates of 18.6% (p<0.001).

Among facilities providing mental health services, 31.2% offered HIV testing, 54.3% offered HIV counseling, 25.7% offered both, and 40.2% offered neither (

Table 2). HIV testing rates were significantly higher in facilities offering mental health services, compared with those not offering such services (31.2% versus 24.1%), with an adjusted estimate of the difference in the testing rates of 3.4% (p<0.001). HIV counseling was significantly higher in facilities offering mental health services, compared with those not offering such services (54.3% versus 50.2%), with an adjusted estimate of the difference in counseling rates of 4.2% (p<0.001).

Additional analyses showed that 29% (N=4,329) of all facilities offered both mental health services and medication for opioid use disorder, and the adjusted rate of HIV testing in these 4,329 facilities was even higher (47.3%, 95% CI=45.8%−48.7%), as was the adjusted rate of HIV counseling (64.7%, 95% CI=63.3%−66.1%). These rates were significantly higher than rates among facilities offering only mental health services (p<0.001), but they did not differ significantly from rates in facilities offering only medication for opioid use disorder.

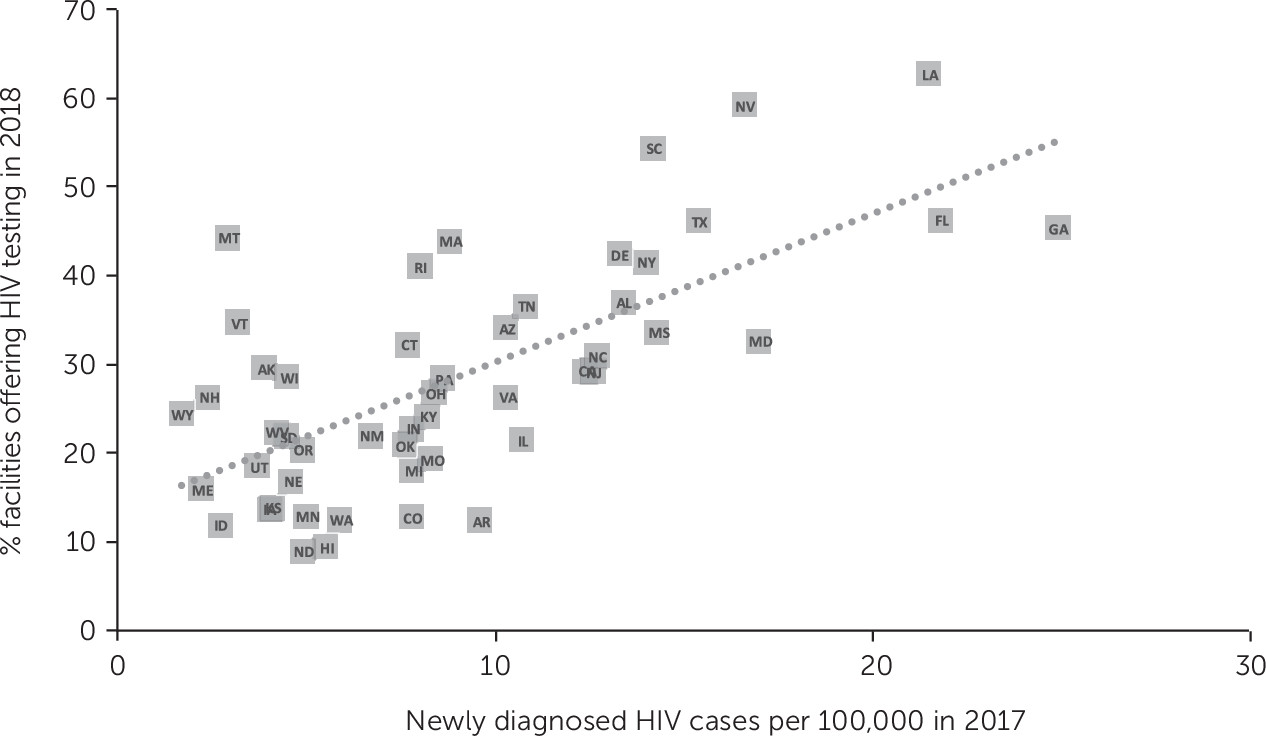

Compared with private nonprofit facilities, private for-profit facilities were less likely to offer HIV testing (odds ratio [OR]=0.66, 95% CI=0.53–0.83, p<0.001) and government facilities were more likely to offer HIV testing (OR=2.10, 95% CI=1.45–3.03, p<0.001). Payment type accepted (e.g., no payment, cash, private insurance, Medicaid, or Medicare) was not associated with HIV testing. Higher background state-level HIV incidence was related to an increased proportion of facilities offering HIV testing (R

2=0.48) (

Figure 3).

Discussion

Among U.S. facilities reporting to N-SSATS, 29% offered HIV testing, consistent with prior reports in these settings (

16). We found little change from prior estimates of HIV testing in these settings between 1995 and 2005 (27% to 29%) (

12), despite increasing HIV incidence, updated 2006 CDC guidelines, new policies that incentivize or require reimbursement, and a decline in the rate of uninsured adults (

12). This low rate of HIV testing is a missed opportunity for early HIV diagnosis, treatment, and prevention, particularly at a time when the nation is grappling with the impact of the opioid epidemic and investing in the “Ending the HIV Epidemic” initiative, which features testing as a key strategy (

17). Given the CDC and USPSTF recommendations for routine HIV testing and the higher-risk population served, universal HIV testing in substance use treatment facilities could help identify individuals who are unaware of their HIV status, link those who are newly diagnosed to care, reengage those previously diagnosed but not currently retained in care, and initiate HIV prevention interventions for those who test negative (

1).

Among facilities offering medication for opioid use disorder, fewer than half offered HIV testing. Although this rate was significantly higher than in facilities not offering such medication (16%), sites offering medication for opioid use disorder are more likely to treat people who inject drugs. Although our data show some improvement in these settings, compared with data from prior smaller studies in similar settings in 2011 (

16), the results are nevertheless concerning, because people with opioid use disorder—even those on medication for opioid use disorder—are more likely to engage in HIV-related risk behaviors, including sexual risk and high-risk injection drug use (

18). Notably, the CDC, the National HIV/AIDS Strategy, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and SAMHSA all encourage routing HIV testing in opioid treatment programs or integration of HIV and substance use disorder services (

19).

HIV testing availability was higher in facilities offering mental health services, compared with those not offering such services (31% versus 24%). These modestly higher rates of testing availability may reflect the influence of organizational characteristics—that is, facilities offering behavioral health care may simply offer more services in general—or may reflect need-based policies responding to the perceived presence of populations at higher risk of HIV. Given the low prevalence of HIV testing among people with serious mental illness served in community mental health settings (

11), improving testing in substance use treatment settings could help fill this critical testing gap.

Finally, although we found a positive association between state-level incidence rates of diagnosed HIV and rates of HIV testing in state substance use treatment facilities, adherence to universal HIV testing recommendations was low even in states with high HIV burden. For example, fewer than half of all facilities in New York and California offered HIV testing (

Figure 1 and table in

online supplement). In fact, in only three states (Louisiana, Nevada, and South Carolina) and the District of Columbia did 50% or more of facilities offer HIV testing. Considering how widespread the low rates of HIV testing in substance use treatment facilities were across the United States, leadership at the federal and state levels may be needed to increase testing (

3).

Although it is important to document how HIV testing practices fall short of guidelines, barriers to adoption should be further investigated systematically, and intervention strategies should be tested. One possible barrier to HIV testing is that many substance use treatment facilities are rooted in a 12-step philosophy, and providers may be more reluctant to adopt a medical model of care that would include routine HIV testing (

20,

21).

We also found that government-run facilities were more likely than other facilities to offer HIV testing. Given that many of the nongovernment substance use treatment facilities accept federal funding, federal agencies could consider making funding contingent on the capacity to offer HIV testing or offering incentives to facilities that reach testing targets.

Another approach to increase testing rates in this population involves promoting or encouraging sites to offer rapid, on-site HIV testing with immediate results at substance use treatment facilities. Multiple randomized clinical trials in substance use treatment facilities have shown that offering this testing service more than triples the proportion of clients who receive HIV testing results (

22,

23). Of note, the addition of counseling to rapid HIV testing did not reduce HIV risk behaviors or increase receipt of test results (

23).

It is important to consider the results of this study in a larger context. Most people in the United States who have a substance use disorder, with or without other comorbid mental illnesses, are not in treatment (

24–

26). Although there is a range of reasons for this, one important barrier is the lack of access to services. Examining the system of substance use services currently in place in the United States does not address this much larger problem of people out of care.

As we explore policy solutions aimed at expanding services to treat substance use disorders, our study supports the value of integrated services. Substance use programs that either offered medication for opioid use disorder or mental health services or both had higher rates of HIV testing and counseling, suggesting that programs with a broader range of services are also more likely to address the common medical comorbidities seen in this population, of which HIV infection is a prominent example.

As the nation grapples with the opioid epidemic in particular, new opportunities will arise that aid us in the goal of expanding access to comprehensive substance use services. One example is ongoing efforts to address the underuse of buprenorphine. In January 2021, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services published practice guidelines that allow physicians to prescribe buprenorphine without undergoing additional training and a waiver process (

27). Expanding the scope of eligible providers could remove barriers to treatment by facilitating access and normalizing substance use treatment in a range of health care settings, but broad implementation efforts will likely be critical to move the needle. In addition to this change, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services also issued guidance that all state Medicaid programs are required to cover treatment for opioid use disorders, including medication (

28). Although positive results of these changes may be anticipated, their success needs to be investigated empirically. As the range of settings providing treatment for people with opioid use disorders expands as a result of such policy changes and initiatives, it will also be important to extend access to HIV testing to this broader range of providers, even as efforts continue to expand provision of HIV testing in the licensed substance use disorder facilities that are included in the N-SSATS sample. These settings include, for example, federally qualified health centers, which play a significant role in the care of both people with substance use disorders and those with mental disorders.

Strengths of this study include the size of the data set and geographic diversity. One limitation is that N-SSATS data are self-reported by clinic directors and supervisors and thus may be missing, incomplete, or subject to social desirability bias. The N-SSATS database includes only programs that seek to be listed in the SAMHSA services locator tool and thus likely overrepresents publicly funded sites and underrepresents programs that are primarily funded through patient self-pay or commercial health insurance plans. Additionally, N-SSATS does not have client-level data, excludes facilities serving incarcerated individuals, and does not define the extent or content of “HIV/AIDS counseling.” Finally, although it would have been preferrable to measure sites where the primary focus was providing mental health services, the response data for the pertinent survey question are not publicly available in the downloadable N-SSATS data set. We may have seen different results if the analysis had been limited to facilities that focused on providing mental health services.