Cognitive impairments are hallmarks of schizophrenia (

1,

2) and are barriers to functional recovery from this condition (

3,

4). The impact of pharmacotherapies on cognition of patients with schizophrenia has been limited (

5), and cognitive remediation interventions therefore remain the most promising approaches for improving cognition and functioning among such patients (

6–

8). Nearly two decades of research have established evidence for beneficial and durable effects of cognitive enhancement therapy (CET) (

9) on cognition and functional recovery in the early (

10,

11) and chronic (

12,

13) stages of the condition and among individuals with comorbid substance misuse (

14). CET is a comprehensive, 18-month intervention that integrates computer-based neurocognitive training with structured social-cognitive groups (

9). The effects of CET in early-course schizophrenia have yet to be replicated and may reduce long-term disability. Confirmatory evidence of CET’s efficacy is critical for the continued advancement of treatment for early-course schizophrenia.

The early stage of schizophrenia is hypothesized to be an optimal therapeutic window for cognitive remediation, given that treatments may capitalize on neuroplasticity reserves (

15,

16). Nearly a dozen clinical trials have indicated that cognitive remediation is efficacious for early-course schizophrenia (

8). Findings suggest that, compared with individuals with chronic schizophrenia, those in the early stage of the disease may have greater improvements in cognition and functioning after cognitive remediation (

17,

18), highlighting the potential of these interventions to expedite recovery and prevent long-term disability. In 2009, Eack and colleagues (

10) reported the results of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of 58 individuals with early-course schizophrenia (mean±SD illness duration=3.2±2.2 years) randomly assigned to 2 years of either CET (N=31) or an enriched supportive therapy (EST; N=27) comparison intervention. Compared with patients treated with EST, those treated with CET had significantly greater improvements in neurocognition (Cohen’s d=0.46), social cognition (Cohen’s d= 1.55), social adjustment (Cohen’s d=1.53), and psychiatric symptoms (Cohen’s d=0.77).

Although promising, the results of this initial trial of CET for early-course schizophrenia were based on a modest sample size of patients with schizophrenia at a single study site. The current study sought to confirm the previously observed positive cognitive and behavioral impacts of CET on patients with early-course schizophrenia in a larger two-site clinical trial. On the basis of findings from previous trials, we hypothesized that CET-treated participants would have significantly greater improvements in the primary outcomes of cognition and social adjustment compared with patients in an active supportive therapy.

Results

Table 1 presents participants’ baseline characteristics across study sites and treatment groups. Overall, the participants were in their mid-20s (24.8±5.4 years), and most were male (N=76, 75%), had been ill for 3.7±2.3 years, and had some college education (N=69 of 94, 73%). Most participants (>75%) had a schizophrenia diagnosis, and about one-half had a history of substance misuse. The CET group had significantly more men than the EST group, but the two treatment groups were otherwise well matched across the demographic characteristics. The overall sample of the current study was similar to that in the previous CET trial (

10) on several key demographic characteristics, including age (25.9±6.3 years), sex (N=40, 69% male), illness duration (3.2±2.2 years), and education (N=39, 67% with some college) of the previous sample.

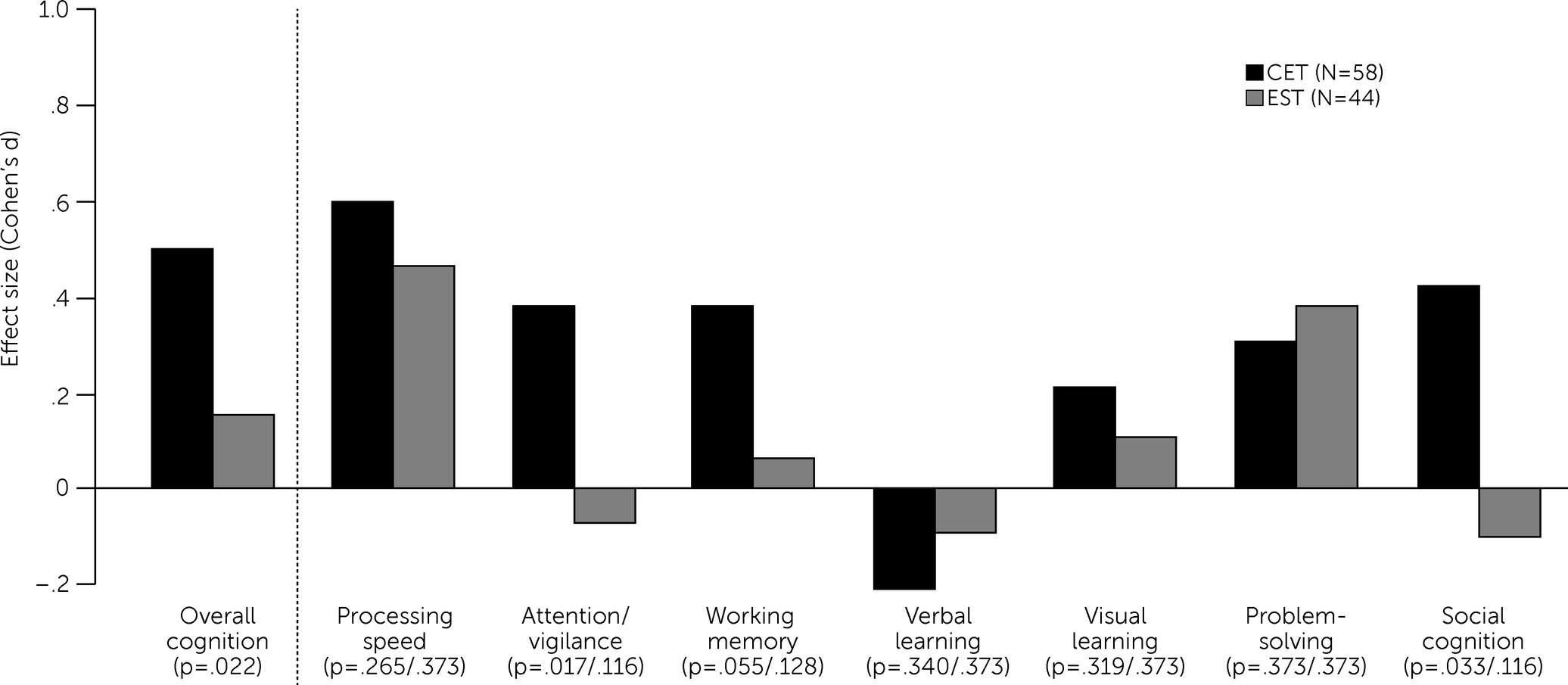

As shown in

Table 2, for the intent-to-treat, mixed-effects analyses, CET had beneficial effects on overall cognition relative to EST both at 9 months (Cohen’s d=0.44, p=0.003, one tailed) and the end of treatment at 18 months (Cohen’s d=0.35, p=0.022, one tailed), confirming the efficacy of CET for improving overall cognition (see the

online supplement for trajectory plots). The effects of CET on improved social cognition (d=0.52, p=0.033, one tailed) and attention/vigilance (d=0.46, p=0.017, one tailed) were also significant at 18 months (

Figure 1 and

online supplement). The p values for social cognition and attention/vigilance did not remain statistically significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons. No statistically significant difference in the social adjustment effect between the treatment groups was observed, and both groups had medium-to-large improvements in social adjustment (

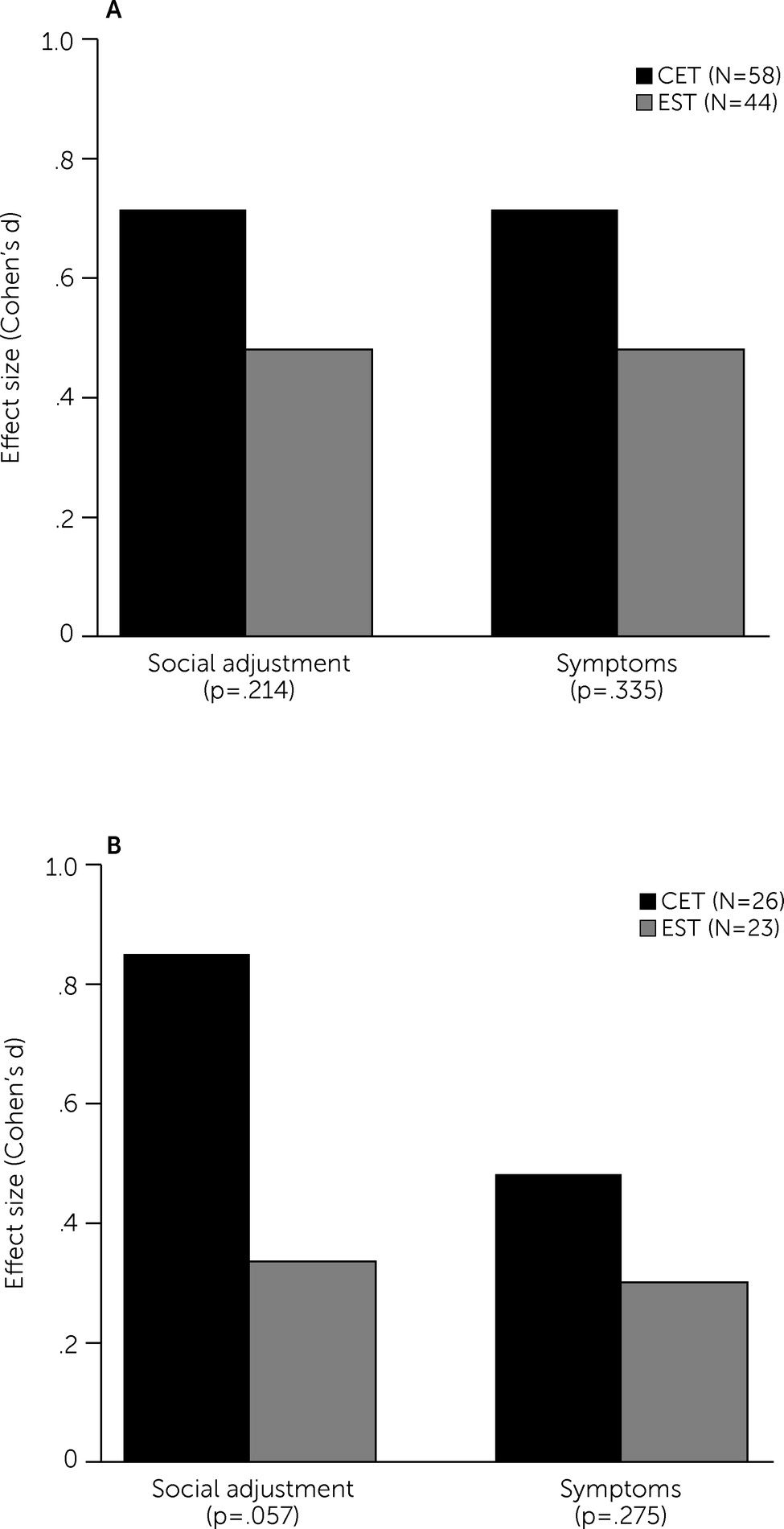

Table 2 and

Figure 2, panel A). With regard to social adjustment domains (see

online supplement), CET’s largest effect was on major role adjustment relative to EST. Finally, no significant group × time interaction was observed for the symptom composite, with both groups having moderate improvements (

Table 2 and

Figure 2, panel A). The sizes of beneficial effects of CET on symptom measures were small to medium and were primarily observed for negative symptom measures (see

online supplement).

Examination of treatment completers at 18 months clarified the effects of CET compared with EST on social adjustment; the effect size of CET on this domain (Cohen’s d=0.51) was more than double that of the intent-to-treat analysis (Cohen’s d=0.23) and nearly reached the standard threshold for statistical significance (of p<0.05; p=0.057,

Table 2 and

Figure 2, panel B). Effects on cognition and symptoms were similar to those found in the intent-to-treat analyses (

Table 2 and

online supplement).

Discussion

This large multisite RCT sought to confirm the previously reported beneficial effects of CET on cognition and social adjustment of patients with early-course schizophrenia (

10). Our results confirmed the overall cognitive benefits of CET and tentatively confirmed its social-cognitive benefits, relative to EST, in both intent-to-treat and treatment completer analyses. The beneficial effects of CET on social cognition were no longer statistically significant after the analyses were adjusted for multiple comparisons, but the significant unadjusted results aligned with those of the previous trial of CET for early-course schizophrenia (

10). In both analyses, CET had a particularly positive effect on attention/vigilance. Effects on social adjustment were not confirmed in the intent-to-treat or treatment completer samples, because both groups had considerable improvements in functioning. Although the differential effect of CET on social adjustment did not meet the conventional threshold for statistical significance (i.e., p<0.05) in the completer analyses (p=0.057), the noticeable increase in the 18-month between-group effect size from the intent-to-treat (Cohen’s d=0.23) to the treatment completer (Cohen’s d=0.51) analyses suggest a functional advantage of completing the full CET treatment. Overall, these findings confirm the beneficial cognitive outcomes of CET for patients with early-course schizophrenia. CET also had a positive impact on social cognition and attention/vigilance. The social adjustment effect observed in the previous CET trial (

10) was not confirmed, but our results indicate that the greatest functional benefits are likely gained among those who complete the entire CET treatment.

The results of this confirmatory trial add further evidence for the benefits of CET for patients with early-course schizophrenia and have important implications for advancing cognitive remediation approaches. It is particularly notable that CET’s effects on social cognition were the largest among all its effects on cognition, consistent with findings of previous trials indicating that CET yields consistent and large improvements in this domain (

10,

12,

14). The social-cognitive effect size was more modest in the current study, perhaps because of reliance on blinded performance-based assessments and the significant attrition rate. Neurocognitive gains were observed mostly in attention/vigilance, an observation that was different from the improvements mainly in verbal memory and problem-solving noted in the initial CET trial (

10). These differences between our studies likely reflect the updated measurement battery to the MCCB, which includes attention/vigilance, not assessed in the initial trial, and both verbal and nonverbal working memory measures, of which our previous trial assessed only the former. Further, the problem-solving measures, which exhibited an effect in the initial trial, are not comparable to the measures in the MCCB used in the present study.

The findings regarding social adjustment effect sizes may reveal the importance of treatment engagement and exposure in translating cognitive benefits to meaningful functional improvements. CET begins with attention training for the first 3–6 months in participant pairs to encourage socialization, after which the social-cognitive groups are initiated and proceed concurrently with neurocognitive training. The social-cognitive groups focus not only on improving social cognition, but also on applying cognitive gains to daily life. Apparently, the later components of CET may be essential to achieving functional improvement through cognitive gains. Both social and nonsocial cognitive improvements during CET have been shown to mediate functional improvement in early schizophrenia (

40,

41). Future research is needed to confirm that cognitive gains, especially during the later phase of CET, mediate functional improvement. It is noteworthy that the CET participants continued to make gains in the primary outcomes from 9 to 18 months (

Table 2). These findings are consistent with previous meta-analytic evidence indicating that short-term neurocognitive training does little to improve functioning without integration into broader psychosocial treatments (

7). The results of this confirmatory trial suggest a benefit of completing the full 18 months of CET rather than only half of the treatment. Future studies are needed to examine the minimal dosage of CET needed to achieve a significant functional benefit in early-course schizophrenia.

Several limitations of this study temper our conclusions. First, this study had a high attrition rate, which reduced statistical power to detect significant treatment effects at 18 months. Attrition is often greater in studies of early-course schizophrenia, a period of the condition during which patients are more ambivalent about treatment (

42–

45). The attrition rate of the previous CET trial was 21% (

10), and the current trial had more than double this rate. The previous and current study samples were demographically similar, but rates of past lifetime substance misuse 3 months before study enrollment were noticeably higher in the current sample, which may have been related to the difference in attrition rates between the two studies. However, this was an anecdotal observation, and it will be important to further investigate factors that might explain the differences in attrition and findings between the two studies. In the current sample, completers and noncompleters significantly differed in age, IQ score, illness length, and antipsychotic medication dose (see the

online supplement), likely indicating a selection bias. It is essential that future research identify approaches to promote engagement in longer-term treatments that could reduce disability.

Second, CET and EST are manualized and differ in clinician contact hours. Consequently, we were unable to match clinician contact between the two groups. To account for any potential clinician effects on differential change between CET and EST, the study was designed such that the same clinicians provided both treatments. As previously mentioned, the number of attended sessions did not influence changes in the outcomes. Third, the modalities of the treatments were different—CET is group based and EST is individual based. Exposure to the social context of a group in CET, in addition to computer-based neurocognitive training in pairs (

46), could have contributed to some of the improvements in social cognition and functioning, and it will be important for future studies to examine the impact of group versus individual treatment on these domains. Finally, we did not examine CET-related mechanisms of cognitive and behavioral changes because the chief goal of this study was to confirm the previously observed cognitive and behavioral effects of CET for early-course schizophrenia. Confirmation of earlier observations of neurobiological mechanisms underlying the benefits of CET (

47,

48) is a critical next step for advancing this intervention, and such confirmatory studies are forthcoming.