Evidence-based treatments (EBTs) for psychiatric disorders exist but are not routinely delivered (

1), often because of a lack of available training. In-person workshops are the most common training method, but the impact on the skills over time is limited without follow-up consultation (

2). A scalable alternative may be the train-the-trainer approach (

2), which centers on the development of a local trainer who then trains other therapists and serves as an in-house coach. Although some previous studies on this approach exist (

3–

5), they have major limitations (e.g., small samples, no comparison group, and no assessment of implementation outcomes).

To address these limitations, we recently compared the outcomes of two methods of training therapists to treat depression and eating disorders on college campuses with interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT): expert training plus 12 months of expert consultation (given the limited utility of training without subsequent consultation) versus the train-the-trainer approach (

6). Outcomes of implementation and effectiveness (

7), respectively, included intervention fidelity, composed of adherence (i.e., delivering treatment as outlined) and competence (i.e., skill in implementing the treatment) (

8), as well as IPT knowledge. IPT was selected as the disseminated EBT because it has a wide clinical range (i.e., it is an EBT for two common psychiatric disorders among college students: depression and eating disorders) (

9), which can increase adoption (

10). The results indicated that, in the months immediately posttraining (while the expert consultation continued), the train-the-trainer approach produced outcomes comparable to those of the expert approach for adherence and IPT knowledge and was superior on competence (

6). Another key metric of implementation success is maintenance, or the extent to which a behavior is sustained ≥6 months after the intervention (

7). In contrast to research on the initial effects of EBTs, relatively little work has reported long-term outcomes (

7). In a review on sustainability or maintenance of new programs, Wiltsey Stirman et al. (

11) found that most studies were retrospective and that half of them had relied on self-reports to assess long-term effects.

Theoretically, the train-the-trainer approach could have greater maintenance than standard approaches because of the availability of support from an in-house champion, but little research has explicitly investigated maintenance. Martino et al. (

3) examined effectiveness of expert-led and train-the-trainer strategies for teaching motivational interviewing. Both approaches resulted in similar adherence and competence at posttraining and the 12-week follow-up (

3). The authors attributed the lack of a difference at follow-up to the fact that the trainers in the train-the-trainer condition were evaluated as being less skillful in covering the material than the experts and that trainers had activities added to their workloads rather than supplanting other activities.

In the current study, we aimed to build on the relatively limited literature on the train-the-trainer approach, especially regarding maintenance. As such, we compared the maintenance of outcomes for the expert and train-the-trainer methods for training therapists at college counseling centers to implement IPT for students with depression and eating disorders. The primary outcome was therapist fidelity to IPT (comprising adherence and competence) as assessed via audio recordings of therapy sessions; therapist knowledge of IPT was a secondary outcome. These outcomes were assessed after consultation with the expert had ceased in the expert condition (7 months later, on average). We hypothesized that the train-the-trainer approach would be superior to the expert training approach.

Methods

Complete details of the study have been previously reported in an article describing the primary outcome (

6), but key aspects are outlined here. The sample included 24 colleges with a counseling center. Centers were randomly assigned to either the expert or train-the-trainer approach. Each center had at least three therapists interested in the study and a staff member interested in serving as study director. Therapists who treated students at least 25% of the time provided informed consent and were enrolled in the study. Participating therapists obtained informed consent from up to two student patients of their choosing, who were eligible if they were age ≥18 years with symptoms of depression or eating disorders (excluding anorexia nervosa, for which IPT is not an EBT). Therapists decided whether the patient met these criteria by using their usual assessment procedures during each study phase: baseline (i.e., before IPT training), posttraining (but during the expert consultation period), and maintenance (after the consultation in the expert condition had ceased). The therapists were asked to submit audio recordings for all sessions (up to eight) with each student patient. Two audio recordings were rated for each patient during each study phase: one from session 1 and one from a randomly chosen later session. On average, maintenance data were collected 12.8 months after the last submitted posttraining session (range 5.7–29.9 months), which was 19.1 months after training (range 13.5–33.3 months); that is, maintenance data were collected about 7 months after the end of the expert consultation period. The timing of collection of maintenance data did not statistically significantly differ across conditions (the mean±SD was 15.6±8.5 months for the expert training group and 10.7±3.6 months for the train-the-trainer group). At each site in the train-the-trainer condition, one trainer was selected by the study’s director at that center. The study received institutional review board approval at the coordinating sites and participating colleges.

Regarding the training conditions, sites in the expert condition were provided with a 2-day workshop in IPT, conducted by a study team member with IPT expertise. Participating therapists were provided a manual, and the workshop included a review of key IPT principles and procedures, role-playing, and case examples to demonstrate IPT treatment phases. Therapists at each site in the expert condition had the opportunity to engage in a 1-hour consultation call with the study team member who conducted the workshop every month for up to 12 months after the workshop.

In the train-the-trainer condition, trainers attended two workshops; the first 2-day workshop was identical in content to the workshop provided in the expert condition and was designed to teach participants to conduct IPT. The second workshop provided training in teaching IPT to others. After the first workshop, each trainer was encouraged to use IPT to treat up to two patients. The study team member who conducted the IPT training reviewed a selection of recorded sessions and provided feedback to the trainers. Once the trainers had trained their colleagues in IPT, they were encouraged to meet with them weekly for 1-hour group consultation sessions. Trainers were also encouraged to join monthly group review calls with the study team member who had conducted their training and with other trainers.

Three measures were used to assess outcomes during each study phase: therapist adherence to, competence in, and knowledge of IPT. Adherence and competence were assessed through listening to audio recordings of therapy sessions, by raters blinded to condition, using the IPT Fidelity Rating Scale (adapted from the measure developed for the Veterans Health Administration IPT Training Program) (

12). Details are available in the primary outcomes article (

6). Knowledge of IPT was assessed from therapist responses to 20 multiple-choice questions.

Therapist characteristics assessed at baseline included age, gender, race-ethnicity, professional degree, years in present position, attendance at a previous IPT workshop or class (yes or no), experience using IPT with patients in past year (yes or no), and job satisfaction. The Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS) (

13) was used to ascertain degree of acceptance of EBTs. Finally, job satisfaction was assessed with the 14-item job satisfaction scale (

14).

We used standard linear mixed-effects modeling to estimate changes in outcomes from baseline to maintenance. In line with the intention-to-treat principle, we included all participating therapists in the analyses as long as data were available from at least one repeated assessment. For all model estimations, we used maximum likelihood implemented in R, version 3.5 (lme4 package) (

15). For model specification, we used a random intercept model assuming linear change over time. Effect sizes (ESs) are reported as Cohen’s d.

Results

From a total of 184 enrolled therapists in the study, we received audio-recorded sessions from 105 therapists at baseline (48 in the expert condition and 57 in the train-the-trainer condition), from 87 therapists at posttraining (41 in the expert condition and 46 in the train-the-trainer condition), and from 23 therapists during the maintenance period (10 in the expert condition [21% of those providing baseline recordings] and 13 in the trainer condition [23% of those providing baseline recordings]; there was no significant difference between the two groups in the percentage of therapists who provided recordings during the maintenance period. However, one therapist in the train-the-trainer condition provided a tape at both posttraining and maintenance, but not at baseline). Therapists providing data during the maintenance period did not significantly differ from therapists not providing data in terms of age, gender, race-ethnicity, degree, and years in present position and in whether they had taken an IPT class or used IPT during the past year; EBPAS or job satisfaction score; or adherence, competence, or IPT knowledge at baseline or posttraining. There was no significant difference between the two groups in self-reported consultation hours used by therapists during the posttraining phase (9.0±8.8 hours for train-the-trainer group and 12.4±8.1 hours for the expert group).

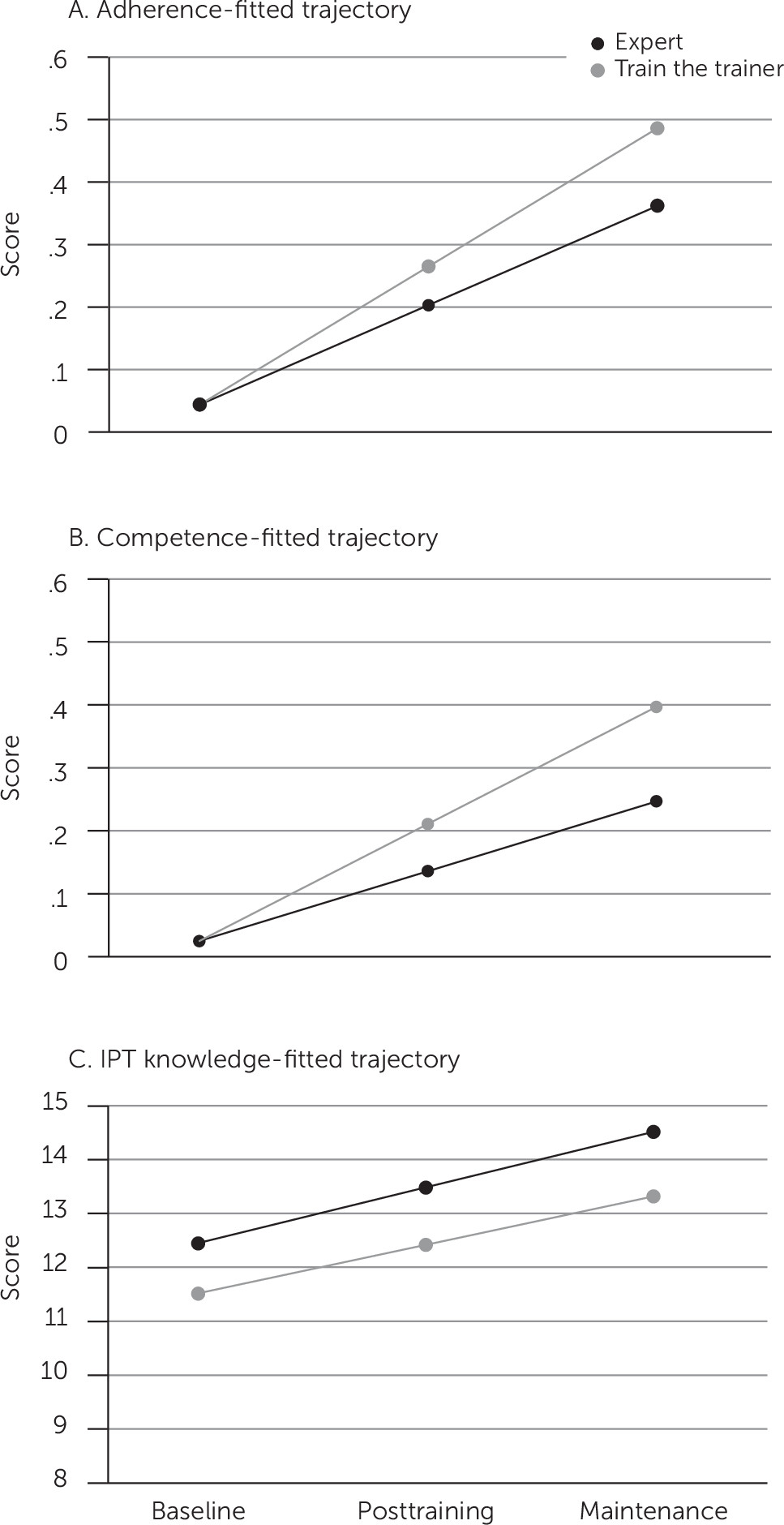

Both training groups showed significant within-group improvement over the three phases (from baseline to maintenance period) for adherence (train the trainer: slope=0.22, ES=0.92, 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.80–1.04, p<0.001; expert: slope=0.16, ES=0.66, 95% CI=0.53–0.80, p<0.001), competence (train the trainer: slope=0.19, ES=0.78, 95% CI=0.65–0.91, p<0.001; expert: slope=0.11, ES=0.47, 95% CI=0.33–0.61, p<0.001), and IPT knowledge (train the trainer: slope=0.90, ES=0.41, 95% CI=0.19–0.63, p<0.001; expert: slope=1.03, ES=0.47, 95% CI=0.23–0.71, p<0.001). Importantly, there were statistically significant between-group effects, indicating greater improvement over time from baseline to maintenance, in the train-the-trainer group compared with the expert group for adherence (slope difference=0.06, ES=0.26, 95% CI=0.10–0.42, p=0.002) and competence (slope difference=0.08, ES=0.32, 95% CI=0.15–0.48, p<0.001). No significant between-group differences were detected in the change in IPT knowledge.

Figure 1 depicts the longitudinal models of change for adherence, competence, and IPT knowledge for the two groups.

Discussion

The train-the-trainer and expert groups showed significant within-group improvement in IPT adherence and competence from baseline through maintenance, with large ESs, but these improvements were significantly greater in the train-the-trainer condition. Both groups also displayed significant within-group improvement in IPT knowledge over time, with no difference between the two conditions. Overall, the train-the-trainer condition resulted in greater maintenance of training effects in terms of adherence and competence, relative to the expert condition.

These findings are important, because they provide empirical support for the theoretical notion that the train-the-trainer approach may be a better long-term training strategy. It is possible that trainers could foster a culture supportive of IPT implementation and that they were able to continue to provide consultation to their colleagues well into the maintenance period; however, future research will be needed to explicitly explore mechanisms that may underlie greater long-term effects. Overall, these results expand previous findings supporting the effectiveness of the train-the-trainer model (

3,

6) and suggest that not only may this approach result in comparable or even superior outcomes in the immediate posttraining period, including for the key implementation outcome of fidelity, but that these effects may extend over time—over 1.5 years, on average, from initial training.

Strengths of this study included the large initial sample of therapists from a wide range of colleges, increasing generalizability, as well as the rigorous fidelity assessment. Our findings also should be interpreted in the context of the study’s limitations, which included the relatively small number of therapists who provided maintenance data (possibly because of high rates of staff turnover). Notably, we observed no significant differences between therapists who did and did not provide maintenance data, and our analytic approach could capitalize on the data available. Future research should assess additional indicators of sustainability (i.e., whether the treatment is formally adopted by the institution) as well as cost-effectiveness.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that the train-the-trainer approach produced improved implementation outcomes (i.e., in adherence and competence) from baseline through the maintenance period that were superior to those of the expert training approach. Given not only its more robust long-term effects but also its potential to train more therapists over time relative to traditional approaches, the train-the-trainer model may be a viable option for increasing dissemination of EBT.