The mortality rate among people with mental and substance use disorders is estimated to be at least two times that of people without these disorders (

1). Higher prevalence of diabetes, asthma, and cardiovascular disease and poorer access to and quality of medical care for people with these disorders likely contribute to increased mortality rates (

2). General health conditions among patients with mental and substance use disorders are often not adequately detected or managed in behavioral health settings because of limited use of general health screening tools, inadequate training, and poorly established relationships with primary care providers (

3). Social, educational, and environmental factors, as well as stigma and discrimination, may create additional barriers to care (

4,

5). These challenges have been amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have limited primary care access even more (

6). Psychiatrists and other clinical support professionals have important roles to play to improve access to and quality of general health care (

7). Even before the pandemic, integration efforts increasingly included technologies such as telehealth and smartphone applications to improve access and patient self-management, which have the potential to break down the generally siloed systems of general health and behavioral health services (

8).

To foster advancement of integration among behavioral health clinics, researchers have identified a need to allow for flexibility in implementation while promoting the adoption of effective general health integration (GHI) interventions. Integrated care consists of a practice team of primary care and behavioral health clinicians working together with patients and families and using a systematic and cost-effective approach to provide patient-centered care. Such integrated care may address mental health and substance abuse conditions, unhealthy behaviors (including their contribution to chronic medical illnesses), life stressors and crises, stress-related physical symptoms, and ineffective patterns of health care use (

9).

Existing frameworks often describe “states” of integration and suggest that certain models, such as physical colocation of behavioral health and primary care services or segmenting services by behavioral and primary care complexity, can bring about or support integration states (

10–

12). However, there is limited evidence supporting these models as well as limited guidance to help clinics advance their integration state. Generally, these frameworks do not provide the flexibility for clinics to prioritize implementation steps by using continuous quality improvement for advancement, which is critical for real-world practice transformation (

13).

To meet this need, the project team developed a stepwise continuum-based (implying that integration can be described in various stages of progress) GHI framework that uses domain-based pathways such as screening and referral to care, ongoing care management, and culturally adapted self-management support, among others (

14,

15) (see the

online supplement to this article for the details of the GHI framework). The framework lays out a roadmap of preliminary, intermediate 1, intermediate 2, and advanced integration stages by domain and combines a strengths-based practice self-assessment with planning features while allowing significant flexibility to set goals and progressively advance integration. Specifically, an individual clinic can tailor its goals to local incentives and reimbursement mechanisms, space limitations, workforce capacity, and population served.

We named our tool a “general health” integration framework to bridge the traditional divide between behavioral health and nonbehavioral health conditions within the broad category of improving general health. Given the evolving literature, we are not putting forth a specific advanced model of integration nor are we asserting that all clinics achieve “advanced” states in every individual domain; the optimal state of integration for clinics may vary by current context. This study describes the use of a framework as an integration practice assessment tool for 11 community behavioral health clinics motivated to advance GHI activities.

Methods

Framework Development

We performed a literature review of peer-reviewed articles published from 2001 to 2020 by searching the PubMed database for the following combined keywords: integrated general care and collaborative care and behavioral health clinics. This search yielded 60 articles that were relevant to GHI in behavioral health settings. We then identified 14 articles that either had an experimental design or were designed as large-scale quality improvement projects. These articles significantly informed the development of the GHI framework domain and subdomain stages (see the

online supplement for a table that indicates the literature relevant to each subdomain).

After developing a draft framework, we recruited and engaged with 12 integration policy and practice experts for a diverse range of perspectives. These experts included five behavioral health clinician executives from New York State (NYS) with integration expertise, five policy and regulatory leaders with national and local expertise, and two behavioral health executives from NYS health plans. Each informant participated in a semistructured interview providing feedback on the framework domains and on current challenges and opportunities for integration. We also sought feedback on the early version from 12 psychiatric fellows working in diverse behavioral health clinics. A revised framework was then presented to 31 stakeholders at an in-person meeting (see the

online supplement for a full list of stakeholders), including the 12 expert informants, behavioral health and primary care providers, consumer advocates, health plan representatives, and NYS regulators and policy makers. Consensus was achieved on the structure, content, and potential utility of the framework.

Eight domains with 15 subdomains are targeted by the GHI framework. Each domain and subdomain has a specific set of evidence-based interventions that are categorized into preliminary, intermediate 1, intermediate 2, and advanced stages of the domains specified (see

online supplement). The major domains include screening and referral to care and evidence-based care for general medical conditions, ongoing care management, self-management supports, multidisciplinary teams, quality improvement, linkages to social service supports, and sustainability. The corresponding subdomains were screening, referral facilitation, evidence-based guidelines for preventive measures, evidence-based guidelines for general medical conditions, medication management, trauma-informed care, longitudinal clinical monitoring and engagement, tools to promote patient activation and recovery, care team, sharing treatment information, integrated care team training, use of quality metrics, linkages to housing and entitlement services, billing and outcome reporting, and regulatory supports. Using a strengths-based approach, we described preliminary stages as usual care, representing no or limited integration activity for the specified domain. Two intermediate stages were described to allow improved ability for sites to choose a lower stage to begin implementation from a preliminary stage (see

online supplement for a list of key supporting evidence per domain). Advanced stages were those that described population-level interventions or required significantly more intensive resources than what most freestanding community behavioral clinics typically acquire. Some subdomains, such as trauma-informed care and sustainability, were not well studied for GHI, but stakeholders judged them to be important integration domains. The framework was designed to enable clinics to perform a baseline, team-based practice assessment and give them the flexibility to choose domains for focused advancement within a specific time frame (6–12 months) according to a clinic’s strategic priorities and available resources (

15).

Conveying intentional and incremental progression of greater integration, the framework allowed clinics to initially identify their integration status for each domain (see

online supplement). For example, a clinic was providing “usual care” if such care was most accurately described by the preliminary stages of a domain. Providing interventions or having workflows at the intermediate or advanced stage reflected a greater level of integrated care for a specific domain. Overall, the framework provided a roadmap for clinics to progressively invest in integration after an assessment of local needs and resources, such as, for example, investments in general medical health screening or training or developing collaborative partnerships with primary care.

Clinic Recruitment and Integration Practice Assessment

Eleven licensed behavioral health clinics in New York City were recruited as a convenience sample through referrals from the stakeholders. Recruitment criteria included executive-level commitment to advance GHI, some recent or current experience in implementing GHI, and receiving most revenues through Medicaid and Medicare. All 11 clinics agreed to use the new framework as a practice assessment.

First, the project team provided a webinar to introduce the framework, describe the practice assessment survey, and define the rating scale for the stages within the domains. An online survey was sent to participating clinics to assess their status of general health integration based on the evidence-based framework for GHI (see

online supplement). The survey questions were divided into three sections: baseline clinic characteristics, practice assessment to identify the stage within each domain or subdomain that was consistently performed at least 70% of the time (this benchmark was used in our previous framework so that practices could have confidence that a practice component was occurring much of the time even if it was not at a universal benchmark level [>90%]), and feedback on the experience of using the framework (

16). Clinics were instructed to assemble a multidisciplinary team, comprising at least a senior behavioral health clinician, a team member providing general health support or education services, and an administrator or quality improvement specialist who was familiar with GHI workflows at the practice. The team assessed the current state of integration for all domains and 15 subdomains. The surveyed clinics also provided a user perspective on the logic and utility of the framework. All 11 clinics completed the survey, and their data were aggregated and deidentified for analysis. At least one technical assistance call was held with each participating clinic to help them confirm the stage that best described their integration interventions in certain domains. The project was reviewed by the Albert Einstein College of Medicine Institutional Review Board and was determined to be in the exempt category.

Results

Clinic Characteristics

The 11 behavioral health clinics each served between 300 and 1,300 patients annually, predominantly insured by Medicaid managed care or Medicare fee for service. In total, 7,143 patients were served by all clinics. The clinics served significant numbers of patients belonging to racial-minority groups, with 45.0% (N=3,214) being Black or African American and 28.0% (N=2,000) Hispanic or Latinx. All clinics identified GHI support from nurse practitioners or registered nurses, with only one clinic reporting a formal collaboration with a primary care physician for consultation. Six clinics reported the use of certified peer counselors to support patient self-management for general health care. Clinics reported some experience with GHI initiatives, including use of electronic health records to extract data such as blood pressure readings and hemoglobin A1c.

Clinic Practice Assessment

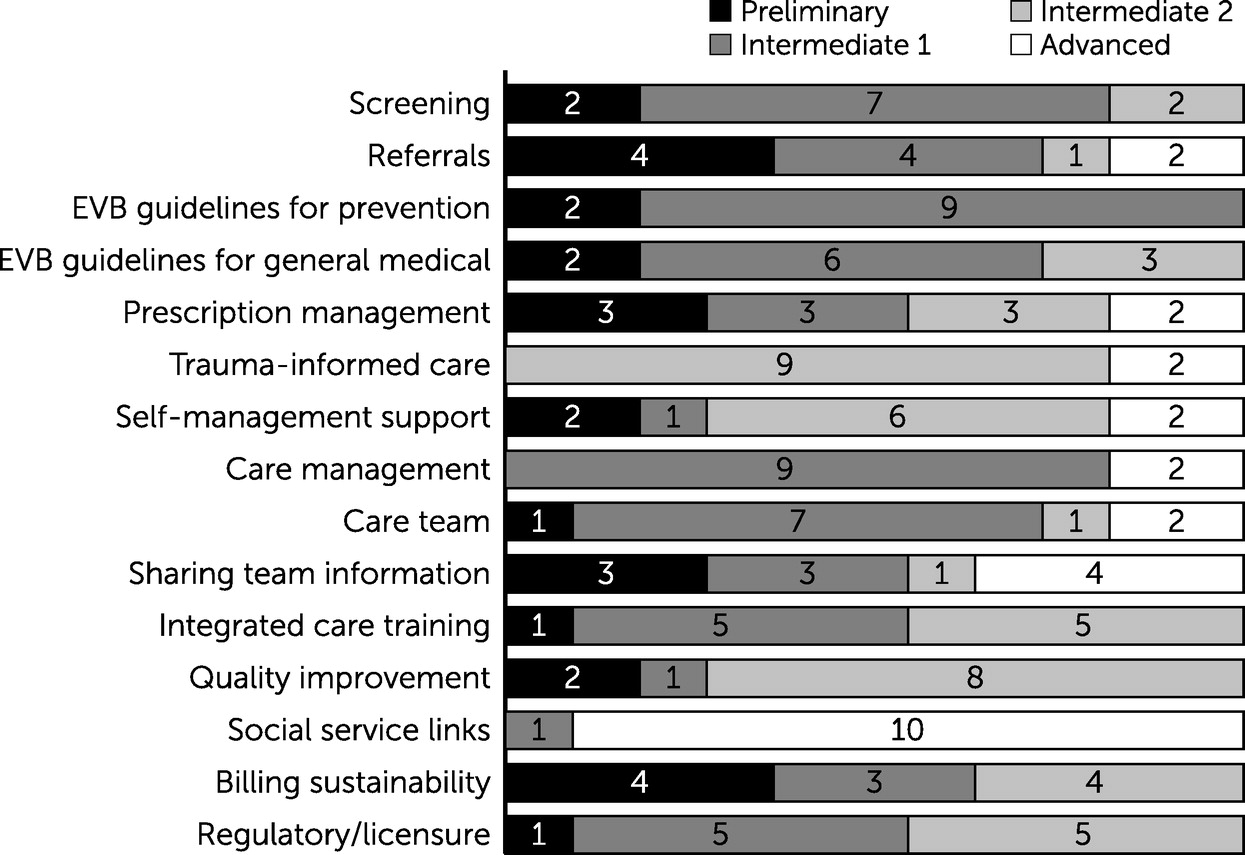

All the practices reported that this was the first time a framework was used to assess their state of GHI. As expected, the current state of GHI among participating clinics varied by domain and subdomain (

Figure 1). Most clinics had strengths (defined here as reporting subdomain stages at the intermediate-2 or advanced stage) in trauma-informed care, self-management supports, quality improvement, and social services linkages. Notably, all clinics reported being in the intermediate-2 and advanced stages for trauma-informed care and social service linkages. The activities related to trauma-informed care that most clinics reported as being at the intermediate-2 stage were routine staff education on trauma-informed care models and limited use of validated screening measures for trauma when indicated. Activities related to social linkages that almost all clinics were undertaking at the advanced stage included use of detailed psychosocial assessments that incorporated a broad range of social determinants of health needs to link patients to social service organizations and resources for improving appointment adherence (e.g., child care and transportation) and enhancing access to healthy food sources.

Opportunities for improvement (defined here as reporting domain or subdomain activities at the preliminary or intermediate-1 stage) were noted in 11 subdomains (see

online supplement for a figure showing variation in the state of GHI among the participating clinics). For most of these subdomains, many of the clinics were mostly performing at the intermediate-1 stage. Notably, the subdomains of referral to care and billing sustainability were especially challenging, given that four sites in each category were performing at the preliminary stage. For example, routine referrals to primary care providers had no or only limited patient follow-up. For billing, these sites reported no or minimal attempts to bill for immunizations, screening, and treatment activities and were mainly supported by grants or other nonreimbursable sources.

Clinic Experiences Using the Framework

Overall, the behavioral health clinics reported positive experiences using the framework. Ten clinics rated the framework as “easy to use.” Seven clinics could readily understand the meanings of the domains, subdomains, and stages within the GHI continuum and how it could assist in planning for stepwise implementation. Occasionally, clinics reported difficulties in deciding which stages to choose within a domain when they perceived that their processes fell between stages. In such cases, we asked them to conservatively choose the less advanced stage. Clarity was also desired on the expected types of screenings and treatment of general health conditions. Sustained funding, electronic health record capability, financial incentives, implementation support, and technical assistance were identified as key supports for advancing the level of integration. The most commonly cited barrier to advancing GHI was inadequate reimbursement for integration activities. Clinics reported that GHI staffing supports such as primary care providers (onsite or through telehealth) and nurses were needed to advance integration efforts and that many staff lacked GHI training or could not expand their scope of services without additional reimbursements or regulatory approval.

Discussion

Behavioral health clinics reported a favorable experience with using the framework as an integration practice assessment. Of note, none of the sites had ever used a framework for GHI planning. Feedback from the sites allowed us to improve the wording and specificity of some stages, including defining prevention activities as distinct from the treatment of general health conditions (see the

online supplement and Chung et al. [

16]). Despite high motivation to advance GHI and strengths in four subdomains, activities of most of the participating behavioral health clinics were preliminary or at the intermediate-1 stage of the integration interventions in the framework.

The identification of domains with demonstrated strengths, such as trauma-informed care, social services linkages, quality improvement, and patient self-management, suggests that many of these practices have a strong foundation for person-centered care and building partnership and trust with patients and families. Strengths in these domains may help practices improve patient activation, adherence, and outcomes as they attempt to advance the other integration domains toward whole-person care (

17–

19). It was also reassuring that some sites used peer-led interventions to support self-management and patient activation, which has been shown to be effective but may not be easily reimbursed (

17).

In contrast, the domains with opportunities for improvement coalesced around areas requiring prioritization because of significant investments in time, training, and resources. In our experience of using a similar framework for integration of behavioral health in primary care (

20), we encouraged a community health focus in which prevalent conditions are identified and focused on improving care outcomes by addressing the related framework domains in a clinic-driven continuous quality improvement process.

Among these initial priorities was improving screening and referral workflows (

Figure 1 and domain 1 in

online supplement), which are of frequent concerns to practitioners who treat patients who have behavioral health disorders. For example, clinics might consider systematic screening for tobacco use as well as ascertaining whether a patient had a preventive visit with a primary care provider in the past 12 months (see

online supplement). Both screening actions are important for primary prevention education and for facilitating specific evidence-based actions, such as referral to tobacco use cessation interventions and connecting patients to primary care appointments. To improve referral facilitation and engagement to primary care, we recommend implementing a collaborative agreement with a community-based primary care facility with mutual accountability for patient referral and follow-up (see

online supplement). Clinics would be advised to set an internal performance metric to monitor for general medical health screening success (i.e., quality improvement) and the number of patients requiring follow-up or intervention (see

online supplement). They are also advised to recoup some of their investment in workflow changes by using available fee-for-service codes (see

online supplement). These examples illustrate how a clinic might use the GHI framework in practice. This process can be replicated and augmented with advances in other domains for other GHI conditions on the basis of local payer incentives. The framework allows clinics to plan and organize their advancement priorities on the basis of existing strengths and resources and can serve as a roadmap encouraging investment in training and workforce development.

Despite the utility of the framework, we note that the clinics reported challenges in sustaining this GHI project. The evidence supporting this framework suggests that behavioral health clinics have an important role in improving outcomes for patients who have significant comorbid general health conditions and risk factors. This framework could be useful in helping providers and aligned advocacy organizations to support policy and payment reforms that span the range from fee-for-service to value-based payments for structural, process, and outcome stages that improve care (

16,

21).

Delivering primary and secondary prevention services envisioned in integration models requires that behavioral health providers embrace an expanded scope of work and increase their collaboration with primary care, despite both disciplines’ having significant national workforce shortages (

22,

23). As shown by our framework, it will be crucial for behavioral health and primary care collaborations to be formalized in order to ensure joint accountability with regard to information sharing, care coordination, referrals, and general health outcomes.

The GHI framework offers a comprehensive vision of integration activities by organizing clinical tasks into domains and subdomains. This organization allows clinics and practices to envision the building blocks of integrated care and may help them identify their current state of GHI and better plan which domains to target for advancement. For example, most clinics mentioned the value of viewing integration as a continuum with varying local supports and incentives that can influence which strategies to implement. The clinics noted that using this framework to develop a team-based consensus on what is working now and what should be achieved next served a facilitating function, especially with the ease of looking at all the domains and stages as a visual tool. To build on this promising framework, further research is needed to validate the use of the GHI framework and determine whether advancing along its domains is associated with improved performance and patient outcomes.

We note the following limitations of our study. The GHI framework was primarily designed with information from the literature and expert consensus input. Although its initial application as a practice assessment in this study was promising, its psychometric properties were not assessed and require further study for validation. The small sample in this study may have limited the generalizability of our findings. Greater use and evaluation are needed to assess the framework’s utility to support GHI advancement in behavioral health clinics over time.

Conclusions

A continuum-based GHI framework is useful for clinic practice assessment. With additional use and further evaluation, this framework may serve as a promising integration planning tool for behavioral health clinics and state health authorities.