Hospital-in-the-Home as a Model for Mental Health Care Delivery: A Narrative Review

Abstract

Highlights

Methods

Study Eligibility

Search Strategy

Data Synthesis

Results

| Study | Year | Study design | No. of patients | Intervention | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Córcoles et al. (49) | 2015 | Prospective cohort study | 896 | HT team vs. psychiatric ED | OR=4.59 (95% CI=2.89–7.30); those in HT are less likely to be admitted to hospital. |

| Rosenberg and Hickie (46) | 2013 | Narrative | — | Hospital avoidance programs | Hospital-based acute care as the major entry point to services is inefficient and against community expectations. |

| Rosen et al. (1) | 2010 | Narrative | — | Mobile crisis teams and assertive community treatment teams | Compromising intensive home-based care will lead to deterioration of preventive interventions. |

| Kalucy et al. (14) | 2004 | Prospective cohort study | 285 | Mental health HAH vs. inpatient ward | Length of stay was 1 week shorter, on average, for those in HAH; 92% of consumers would use HAH again. |

| Huang et al. (45) | 2009 | Semistructured interviews | 65 | Hospital-based home care | Recommendations from thematic analysis include need for multidisciplinary care, increased operating hours, and rapid emergency response. |

| Huang et al. (44) | 2010 | Semistructured interviews | 65 | Hospital-based home care | Further recommendations include need for reduced caseloads and holistic approach (e.g., supported employment). |

| Singh et al. (15) | 2010 | Prospective cohort study (no control) | 111 | HAH service | 7-point reduction on HoNOS, 12.3-point reduction on BPRS, and 3.2-point reduction on the Risk Assessment Scale from admission to discharge |

| Richman et al. (20) | 2003 | Prospective cohort study (no control) | 40 | Outreach team for patients ages >65 years on waitlist for admission | 25% of patients still required admission after an average of 4 weeks. |

| Sjølie et al. (65) | 2010 | Literature review | 35 | CRHTs and HBT teams | CRHT seemed to be effective in reducing hospitalization and might be cost-effective; further research is needed. |

| Klug et al. (66) | 2019 | Systematic review | 3 | Mobile psychiatric care programs for patients ages >60 years | Significant improvements in psychiatric symptoms and psychosocial problems, fewer admissions, and cost-effective |

| Palé et al. (16) | 2019 | Descriptive study | 135 | Psychiatric home hospitalization unit (HBT service) | Improvements in global activity assessment scale by 15 points from admission to discharge. 21-point decrease in PANSS values for those with psychotic disorders. |

| Stulz et al. (42) | 2019 | RCT | 707 | Service model with HT admission alternative vs. without | 30% reduction in hospital days when HT was available; no significant differences in overall treatment duration or clinical and social outcomes |

| Kilian et al. (17) | 2016 | Prospective cohort study | 118 | HT vs. inpatient admission | HT was associated with 4.3-fold difference in HAM-D ratings and 4.5-fold difference in HoNOS score when compared with inpatient treatment (both statistically significant); HT was 7,151 euros less expensive per episode. |

| Crawford et al. (34) | 2004 | Cross-sectional survey | 109 | Patients postdischarge | Preference for home care was elicited in surveys, primarily because of dislike of inpatient care. |

| Giménez‐Díez et al. (50) | 2020 | Cross-sectional survey | 40 | Psychiatric home hospitalization unit (HBT service) | Patient and caregiver satisfaction linked to the person-centered nature of care (as well as high accessibility and availability) |

| Wasylenki et al. (55) | 1997 | Prospective observational study with combination of interviews and surveys | 27 | Intensive HT program for acute psychosis | BPRS score reduced from 41 to 35 pre- and post-HT; reductions from 1.03 to .56 on Family/Caregiver Impact Scale; cost per day for HT was $139.78, compared with $637.00 for inpatient care. |

| Evans et al. (57) | 2001 | Prospective cohort study | 238 | Two types of home-based crisis interventions vs. crisis case management for children and adolescents | Measures in family adaptability, caregiver self-efficacy, child self-concept, and child social competence increased similarly across all programs. |

| Harrison et al. (40) | 2003 | Extension of previous RCT | 292 | Day hospital combined with HT vs. day hospital vs. inpatient care | Costs were £4,053 per patient in day hospital sample, £5,422 per patient in HT sample, and £6,855 per patient in inpatient sample; CPRS score was 31.6 in the HT sample (indicating high level of symptoms successfully treated at home). |

| Lauka et al. (52) | 2013 | Open-ended survey design | 120 | Studied potential ethical situations faced by in-home counselors | Identifies the need for appropriate training and supervision given complex ethical issues faced when working in the patient’s home |

| Cowie (47) | 2019 | Narrative | — | HITH for young adults | Evaluation after 12 months found that 94.4% of caregivers were satisfied with HITH care quality, and 100% found the service convenient; 90% of referrers found the service accessible. |

| Cleary et al. (21) | 1998 | Letter | — | Intensive HT teams with extended hours | References provide evidence that the teams prevent admission and are effective similarly to inpatient care; more research is needed into downsides and costs. |

| Hepp and Stulz (41) | 2017 | Narrative | — | HT | Modest evidence was found for reduced admissions; possibility for caregiver burden and increased suicide risk needs further exploration. |

| Hauth (43) | 2017 | Narrative (position statement) | — | Ward-equivalent treatment in the home | In terms of symptom reduction and social functioning, HT is at least equivalent to inpatient care; HT enables a better understanding of the individual. |

| Carpenter and Tracy (22) | 2015 | Semistructured interviews | 10 | HT teams | Patient views on HT (positive and negative) are presented; increases in psychology, occupational therapy, and peer support input are proposed. |

| Winness et al. (64) | 2010 | Literature review | 13 | CRHTs | Consumer experience is influenced by ready access and availability, as well as partnership care. |

| Khan and Pillay (23) | 2003 | Structured interviews | 61 | Hospital treatment vs. HT | Cultural factors (stigma, religion, diet) influence patient preference for HT. |

| Caplan et al. (9) | 2012 | Meta-analysis | 61 | HITH programs across all specialties | OR=.29 (95% CI=.05–1.65); HT may prevent readmissions, but this was not statistically significant (from analysis of four studies). |

| Iqbal and Nkire (59) | 2012 | Retrospective cohort study | 1,778 | HBT team | 50% reduction in admissions to the inpatient unit in the first 3 years of the HBT team (effect plateaued after this time) |

| Burns et al. (54) | 2006 | Systematic review | 91 | Home-based care | Regression analysis showed that regular home visits and combining health and social care were linked to reduced hospital admissions. |

| Wright et al. (67) | 2004 | Systematic review | 91 | Home-based care | Almost half of the programs had ended by publication date; long-term sustainability of home care programs was linked to hospitalization outcomes. |

| Brimblecombe et al. (62) | 2003 | Prospective cohort study | 293 | Community treatment team providing intensive home care | 21.1% of patients were admitted to hospital; regression analysis showed that high suicidal ideation at outset and previous hospital admissions both predicted hospitalization. |

| Murphy et al. (18) | 2015 | Systematic review | 8 | RCTs of crisis intervention vs. standard care | Crisis intervention reduced repeat admission (RR=.75); mean difference of 5.4 in client satisfaction questionnaires in favor of crisis intervention. |

| Catty et al. (60) | 2002 | Systematic review | 91 | Home-based care | Compared with inpatient control group individuals, patients in HT had hospital stays that were 6 days shorter per patient per month; compared with individuals in a community control group, individuals in HT had a reduction of 0.5 days in the hospital per patient per month. |

| Jacobs and Barrenho (35) | 2011 | Quasi-experimental study | 229 | Districts with and without CRHTs | Trends in mean admissions across districts were similar (whether introduction of CRHT was introduced or not). |

| Wheeler et al. (36) | 2015 | Systematic review | 69 | CRHTs | CRHTs with a psychiatrist had admissions reduced by 40%; 83% of districts with a 24/7 CRHT had a drop in admissions (compared with 74% of districts with a limited-hour CRHT). |

| Muijen et al. (24) | 1992 | RCT | 189 | Home care vs. standard care | Median hospital stay was 6 days in home care group vs. 53 days in hospital group. |

| Smyth and Hoult (25) | 2000 | Debate | — | Home care | Various arguments presented for and against home care |

| Johnson (19) | 2013 | Narrative | — | CRHTs | Key challenges of the CRHT model include integration within the wider system and having care continuity when multiple workers are involved in each crisis. |

| Onyett et al. (37) | 2008 | Questionnaire and interviews | 243 | CRHTs | Many teams reported high assessment loads, understaffing, and lack of multidisciplinary input. Despite high assessment loads, caseloads were lower than expected (59% of the recommended size per population). |

| United Kingdom Department of Health (38) | 2001 | Mental Health Policy Implementation Guide | — | CRHTs | Discusses implementation and key features of these teams |

| Glover et al. (39) | 2006 | Observational study using routine data from local health districts | 229 | CRHTs | Compared with areas without CRHTs, hospital admissions fell by 10% in areas with CRHTs and by 23% in areas with 24/7 CRHTs. |

| Harrison et al. (26) | 2001 | Analysis of referral data | — | Intensive HT team | 20% of patients accepted later had to be transferred to inpatient care; those with severe mood disorders were most likely to need hospital care (35% were admitted). |

| Magnusson et al. (56) | 2003 | Interviews | 11 | Home care | Working in the home environment poses challenges in trying to support self-determination in the face of serious illness or increased risk. |

| Johnson (27) | 2004 | Narrative | — | CRHTs | The evidence base examined is not conclusive; main pitfall of CRHTs could be loss of care continuity. |

| Khalifeh et al. (28) | 2009 | Semistructured interviews | 23 | CRHTs | Most mothers preferred HT, whereas most children preferred parental hospital admission; HT may expose dependent children to additional risks and lack of support. |

| Carroll et al. (48) | 2001 | Narrative | — | CATT | Describes benefits to the team in having clear referral criteria and focus |

| Robin et al. (58) | 2008 | Prospective cohort study | 299 | Mobile emergency team | Proportion of short stays in hospital (<7 days) was three times higher in the experimental group; number of days in hospital was lower in the experimental group across 5 years (main effect was in the first 2 years). |

| Tomar et al. (63) | 2003 | Retrospective cohort study | 40 | Data from two CRHTs treating first-episode psychosis (FEP) | 69% of FEP patients successfully treated at home (small sample size). |

| Gould et al. (29) | 2006 | Prospective cohort study | 111 | CRHTs treating FEP | Only 55% of FEP patients treated by CRHTs remained in the community throughout 3 months (compared with 72% treated by other services). |

| Hunt et al. (30) | 2014 | Retrospective longitudinal analysis | — | CRHTs across the United Kingdom | 14.6 suicides per 10,000 CRHT episodes, compared with 8.6 per 10,000 inpatient admissions; risk factors were living alone (44%), recent major stressor (49%), and recent hospital discharge (33%). |

| Johnson et al. (61) | 2005 | RCT | 260 | CRHT vs. standard care | OR=.19 (95% CI=.11–.32); experimental group was less likely to be admitted to hospital in 8 weeks; no effect on compulsory admissions or client satisfaction. |

| McCrone et al. (31) | 2009 | RCT | 260 | CRHT vs. standard care | CRHT group on average had noninpatient costs £768 higher than those in standard care; with the inclusion of inpatient costs, the costs for the CRHT group were £2,438 lower than the control. |

| Hubbeling and Bertram (32) | 2014 | Client satisfaction questionnaire | 152 | CRHT | Most important for patients was that CRHTs focus on problem solving and crisis resolution. |

| Hopkins and Niemiec (33) | 2007 | Semistructured interviews | 76 | CRHT | Discusses seven key aspects valued by patients |

| Goldsack et al. (51) | 2005 | Interview-based study | 30 | HBT service | 25% reduction in admissions; patients expressed clear preference for HBT; team members were satisfied with their work; caregivers learned skills in managing periods of acute illness. |

Definition of Existing Programs

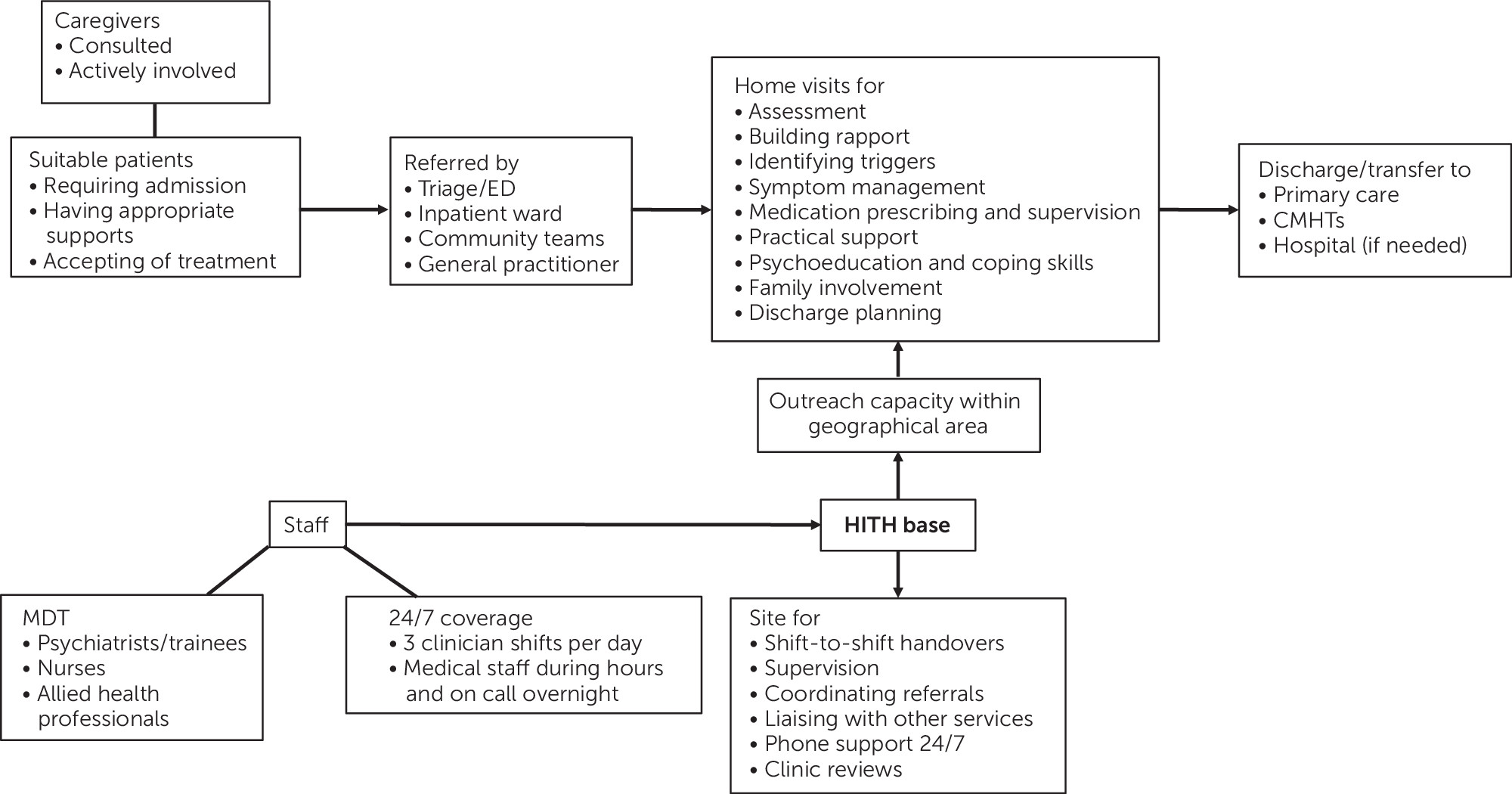

Design and Implementation

Service components and functions.

Suitable consumers.

Staffing and practical considerations.

Implementation barriers and obstacles.

Outcomes

Hospital admissions.

Symptoms and psychosocial functioning.

Consumer satisfaction.

Cost-effectiveness.

Risks associated with home care.

Effect on caregivers.

Discussion

Conclusions

Footnote

Supplementary Material

- View/Download

- 278.85 KB

References

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Keywords

Authors

Competing Interests

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBLogin options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).