High rates of failed care transitions after inpatient psychiatric care are a critical quality concern. In the United States, 42%−51% of adults (

1–

3) and 31%−45% of youths (

3–

5) do not attend mental health visits within 30 days after discharge. Failed care transitions increase the risk for relapse, hospital readmission (

6–

13), homelessness (

14,

15), violent behavior (

16,

17), criminal justice involvement (

18,

19), and all-cause mortality, including suicide (

20–

24).

Routine discharge planning, including scheduling an outpatient appointment with a community-based psychiatric provider before discharge, significantly improves the likelihood of patients attending visits after discharge (

25–

28). Recent analyses of the sample examined in the current study described patient, hospital, and service system characteristics associated with patients receiving routine discharge planning practices (

29) and have documented that, after controlling for a range of these characteristics, patients who had an appointment scheduled prior to discharge had a significantly greater likelihood of receiving timely outpatient psychiatric care (

30).

An important factor to consider, however, is the patient’s history of engagement in outpatient care. Patients who were not engaged in psychiatric care before admission are much more likely to fail to transition to outpatient care after inpatient psychiatric discharge (

1,

2,

30). Hospital providers may administer less discharge planning for patients known to not follow up with care or when patients are being discharged against medical advice or are otherwise refusing outpatient follow-up. It is important to know whether routine discharge planning practices are effective and should be encouraged for these patients.

In this study, we explored whether the strength of associations between scheduling aftercare appointments during routine psychiatric inpatient discharge planning and postdischarge follow-up care varied by level of patient engagement in outpatient psychiatric care before hospital admission. We hypothesized that the association between appointment scheduling and attendance at follow-up appointments would be weaker for patients who were only partially engaged in care before the admission and that appointment scheduling would not have a significant impact on follow-up for patients who received no psychiatric care during the 6 months prior to inpatient psychiatric admission. These hypotheses were based on the expectation that individuals who do not routinely engage in outpatient care may be more likely to have characteristics (e.g., co-occurring substance use disorders) or circumstances (e.g., housing instability) that contribute to their poor engagement and that a routine discharge planning practice, such as scheduling an aftercare appointment, may be less likely to influence the impact of these factors on patient follow-up.

Methods

Data Sources and Study Population

Data for this study were obtained from four sources: New York State Medicaid claims records (including data on patients and clinicians), the 2012–2013 American Hospital Association Annual Survey (

31), the 2012–2013 Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) Area Resource File (

32), and a 2012–2013 New York State Managed Behavioral Healthcare Organization (MBHO) Discharge File created as part of a statewide quality assurance program in New York State aimed at reviewing discharge planning practices related to inpatient psychiatric admissions. The Area Health Resource File and Annual Hospital Survey data are available from the federal HRSA and the American Hospital Association, respectively.

The eligibility criteria for study participants included patients who were <65 years old, were admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit during 2012–2013 with a principal diagnosis of a mental disorder (only the first observed inpatient admission was included for patients who had more than one inpatient psychiatric admission during 2012–2013; ICD-9 diagnostic codes for mental disorder included 290, 293–299, 300–302, and 306–316), had an inpatient stay of ≤60 days, were discharged to the community, were continuously enrolled in Medicaid for the 60 days after discharge, and were enrolled in Medicaid for at least 11 of the 12 months before their inpatient admission. Dual Medicaid-Medicare–eligible patients were excluded because of a lack of available information on Medicare service use. A total of 18,793 patients met the criteria for inclusion. The study was approved by the New York State Psychiatric Institute Institutional Review Board, which granted a waiver of individual consent.

Variables of Interest

The main outcomes were attending an outpatient psychiatric service within 7 or 30 days after being discharged from inpatient psychiatric care. An outpatient psychiatric service was defined as a Medicaid claim for a visit at a mental health–licensed outpatient setting or any outpatient service, with a primary diagnosis of a mental disorder. The New York State Office of Mental Health requires that hospitals schedule appointments within 7 days of discharge.

The primary independent variable was a categorical measure of engagement in psychiatric care during the 6 months prior to inpatient admission. We adapted an approach to measuring engagement developed by researchers studying primary care (

33) and veteran psychiatric populations (

34) that measures intensity and regularity of outpatient visits as proxies for engagement in services. Descriptive analyses of the intensity of regularity of outpatient mental health visits focused on the 6 months before each patient’s inpatient psychiatric admission. After review by clinicians and clinical administrators, who were members of the research team, we defined an engagement variable based on the following criteria: enough participants should be in each category to allow for meaningful analyses, and the category definitions should reflect expert clinicians’ experiences with patients who have variable levels of engagement in ambulatory care. Our engagement variable included four levels: high engagement (four or more visits with a psychiatric provider with visits in at least 4 of the 6 months), partial engagement (four or more visits but with all visits occurring in ≤3 of the 6 months), low engagement (one to three visits in the 6-month period), and no engagement (no visits in the 6-month period).

Covariates

We included as covariates several patient, hospital, and regional service system characteristics that previously have been associated with discharge planning and postdischarge continuity of care for patients with psychiatric disorders (

1,

2,

30,

35,

36). Patient characteristics included demographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender, race-ethnicity, length of stay [LOS], homeless at admission), primary inpatient discharge diagnosis, co-occurring substance use diagnosis at discharge, and burden of co-occurring medical conditions, measured with an Elixhauser Comorbidity Index (ECI) (

37). Established algorithms were used to develop an ECI score for each discharge on the basis of clinical diagnoses reported in inpatient and outpatient claims for all Medicaid-reimbursed health care services during the 12 months before inpatient admission (

38,

39).

Hospital-level characteristics encompassed the number of hospital beds, hospital ownership, percentage of discharges for patients insured by Medicaid, whether hospitals provided outpatient psychiatric services, whether the hospitals had resident teaching status, percentage of psychiatric discharges for patients with a substance use disorder diagnosis, and percentage of psychiatric population with two or more psychiatric discharges. System-level characteristics described counties in which patients resided on the basis of the percentage of county population in poverty, the number of psychiatric workers per 100,000 residents, and whether the counties had urban or rural population density.

Data Analysis

The proportions of patients admitted to inpatient psychiatric units meeting criteria for each of the four outpatient levels of engagement were calculated and stratified by each patient, hospital, and service system characteristic. Unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 99% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for each characteristic by using logistic regression models to describe the effect of each variable on the probability of having engaged in care prior to admission, comparing the partial, low, and no-engagement groups with the high-engagement group as the reference.

Logistic regression models were used to estimate the associations between having an outpatient psychiatric appointment scheduled and 7- and 30-day attendance at outpatient psychiatric services. We fit models testing these associations within each of the four groups on the basis of level of engagement 6 months before psychiatric inpatient admission and adjusted for all other patient, hospital, and service system covariates. For these associations, adjusted odds ratios with 99% CIs were calculated as measures of effect on the probability scale. Generalized estimating equations were used for all models to account for the clustering of observations within hospitals. In this large, exploratory study, no adjustments were made to the many CIs and p values, which should therefore be interpreted with caution. All analyses were performed in SAS, version 9.4.

Results

The final study sample included 18,793 psychiatric inpatient admissions involving 18,793 unique patients, all of whom were discharged to the community. Grouping the patients on the basis of level of engagement with psychiatric services during the 6 months before inpatient admission identified 7,927 (42.2%) patients in the high-engagement group, 1,968 (10.5%) in the partial-engagement group, 3,648 (19.4%) in the low-engagement group, and 5,250 (27.9%) in the no-engagement group.

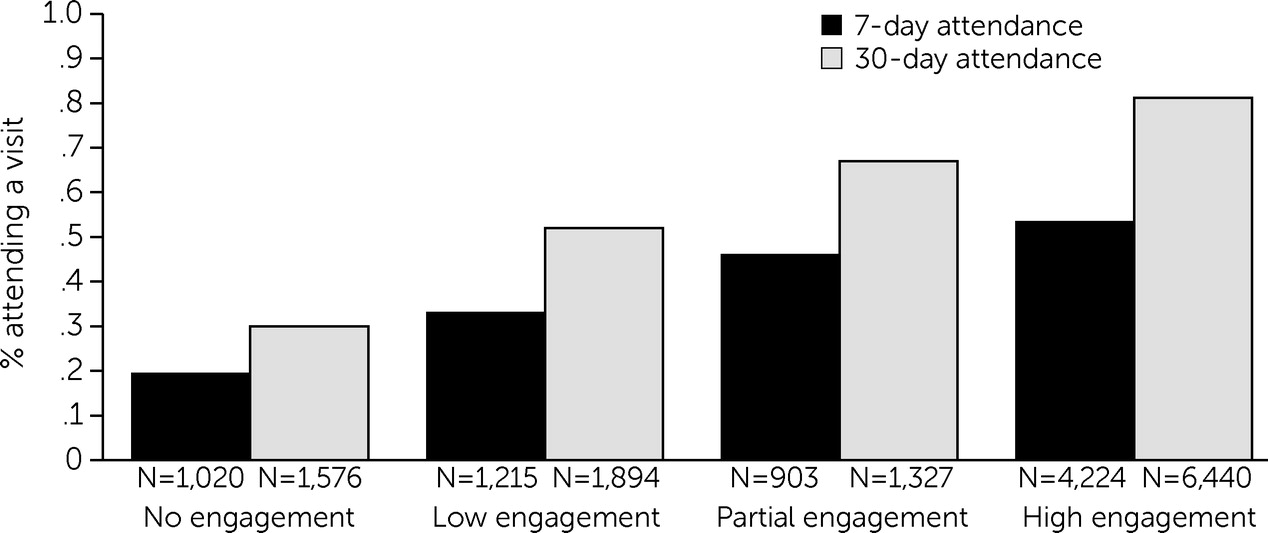

Figure 1 shows 7- and 30-day rates of attending care after discharge for the high-, partial-, low-, and no-engagement groups. Follow-up rates progressively increased by level of engagement in care prior to admission.

Table 1 describes patient characteristics of the total sample and the four engagement groups. Patterns were consistent among the groups and were more pronounced in the groups with lower levels of engagement in care before admission. Compared with patients who were highly engaged in care, those with no psychiatric visits in the 6 months before admission were more likely to be Black (compared with White), older (relative to the 4–12-years-old group), and to have shorter (0–4 days) LOS. Patients not engaged in care prior to psychiatric admission were also more likely to be homeless, have a co-occurring substance use disorder, and have a primary mood disorder (compared with a psychotic disorder) diagnosis and were less likely to have co-occurring medical conditions.

Table 2 lists hospital- and system-level characteristics for the total sample; none of these variables were consistently associated with level of engagement in psychiatric care before admission.

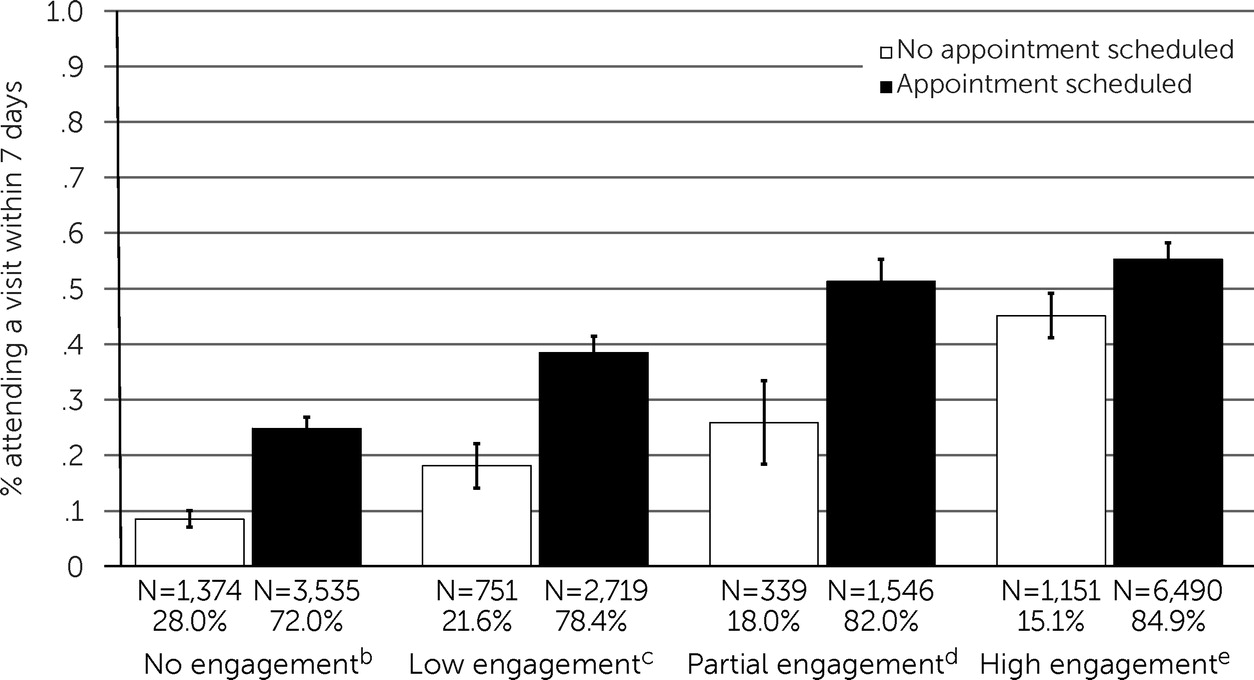

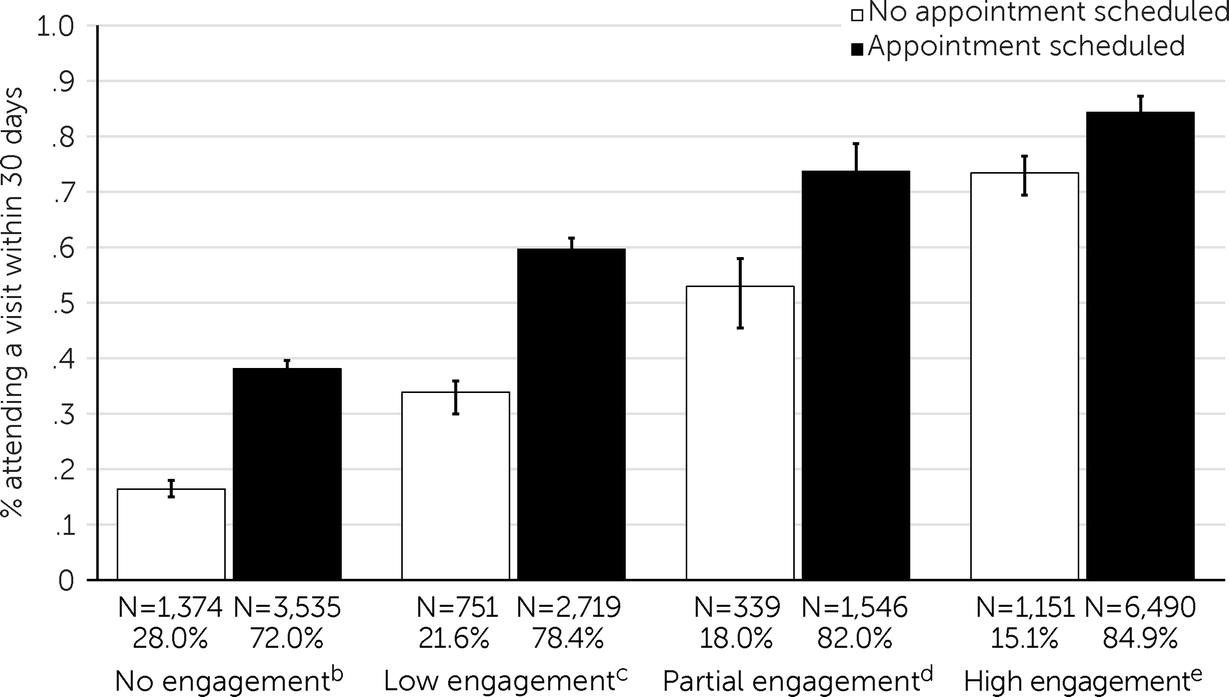

Among those who were highly engaged in care prior to admission, 15.1% (N=1,151) did not have an appointment scheduled. This proportion progressively increased among the other groups; among those with partial, low, or no engagement in care prior to admission, 18.0% (N=339), 21.6% (N=751), and 28.0% (N=1,374), respectively, did not have an appointment scheduled before discharge. (Ns and percentages were based on data with missing information about whether some patients attended an appointment.)

Figures 2 and

3 present the proportions of patients attending outpatient appointments within 7 and 30 days after discharge, respectively, adjusted for the patient, hospital, and service system characteristics described in

Table 1. For each of the four patient groups defined on the basis of level of engagement in care prior to admission, scheduling an outpatient appointment as part of the patient’s discharge plan was significantly associated with attending an initial outpatient psychiatric appointment within both 7 and 30 days after discharge. In the group of patients who had not received any outpatient care in the 6 months before admission, those for whom the inpatient team scheduled an outpatient appointment as part of their discharge plan were approximately three times more likely than those who did not receive an outpatient appointment to follow up with care within 7 days and more than twice as likely to follow up within 30 days.

Discussion

This study examined associations between scheduling appointments during discharge planning and follow-up outpatient treatment among patients with varying levels of engagement in care prior to hospital admission. We report three key findings. First, only 42.2% of patients were highly engaged in outpatient psychiatric care in the 6 months before a psychiatric inpatient admission. Second, patients who were less engaged in care before admission were less likely to have an appointment scheduled with an aftercare provider. Third, having an appointment scheduled as part of the discharge plan was associated with successful care transition regardless of the patient’s level of engagement in care prior to the admission.

Our hypotheses that the association between appointment scheduling and attendance at follow-up appointments would be weaker or nonexistent for patients who were partially or not engaged in care before the admission were not supported. Rather, we found that scheduling an outpatient appointment before discharge remained strongly associated with postdischarge follow-up regardless of patients’ level of engagement in psychiatric care prior to admission. Even among patients who received no psychiatric services in the 6 months prior to admission, whose overall follow-up rates were the lowest, those for whom the inpatient psychiatric team scheduled an outpatient appointment as part of the discharge plan were approximately three times more likely than those who had no scheduled follow-up appointment to attend a follow-up psychiatric visit within 7 days and more than twice as likely to attend a visit within 30 days.

Lack of engagement in care prior to inpatient psychiatric admission strongly predicts failed care transitions (

1,

2). We defined four levels of engagement in outpatient psychiatric care based on intensity of services received over a 6-month period before hospital admission. The finding that only a minority (42.2%) of patients met our definition of being highly engaged in care before their hospital admission confirms previous studies indicating that poor access or adherence to community-based psychiatric care is a common antecedent to acute inpatient psychiatric care (

2). Our approach to measuring engagement in outpatient psychiatric care may inform future quality improvement efforts.

In our sample, patient characteristics were more strongly associated with level of engagement in care prior to admission than were hospital or service system characteristics. Two of the significant patient characteristics, being homeless and having a co-occurring substance use disorder, are known predictors of poor treatment outcomes (

1,

14). Patients who had a shorter inpatient LOS were also more likely to have been disengaged from outpatient psychiatric services before hospital admission. This group might include patients who were refusing treatment, were admitted on involuntary holds because of concerns about safety, or were discharged when the treating psychiatrist could no longer identify safety concerns. Other patient characteristics associated with poor engagement in care prior to admission, including older age, being Black, having a primary mood disorder, and not having significant comorbid medical conditions, are more difficult to explain. Of note is the finding regarding Black patients, who have been shown to have lower engagement rates in psychiatric care (

40). Acute psychiatric care systems need to prioritize efforts to better understand and address the needs of Black individuals with psychiatric illness experiencing crises, including the potential impact of provider bias, patient distrust, and institutional racism on access to and retention in care.

Previously published analyses of adult patients discharged to the community after inpatient psychiatric care revealed that 77% had an outpatient appointment scheduled with a psychiatric provider as part of their discharge plan (

29,

35). The current analysis indicated that inpatient treatment teams were less likely to schedule postdischarge appointments for patients who were not engaged in care before admission. This finding may reflect a lack of community providers with available appointment times. In the current and previous analyses (

29), however, we did not find associations between outpatient provider density and scheduling appointments or follow-up attendance. This association may also be because these patients were more likely to refuse discharge planning, or it may reflect a bias on behalf of inpatient providers to offer less discharge planning to patients they believe to be less likely to follow up. Importantly, our findings suggest that inpatient teams should offer to schedule outpatient follow-up appointments for all patients discharged from inpatient psychiatric care regardless of their level of engagement in psychiatric care before hospital admission.

There are several possible explanations for the associations between scheduling an appointment and attending postdischarge visits. For patients who were previously engaged in outpatient care, scheduling an appointment may serve as a reinforcement of the need for timely follow-up and may limit the potential for confusion and discontinuity after discharge. For patients with low or no engagement in outpatient care prior to admission, scheduling an aftercare appointment may create an opportunity for continued care that some patients take advantage of after discharge, despite their prior difficulties accessing treatment. Our data indicate that many such patients take advantage of this opportunity. This finding has important implications; hospital providers who do not offer discharge planning to patients who are leaving against medical advice or otherwise refusing to collaborate on discharge planning should consider revising their policies to ensure that all patients receive a follow-up appointment regardless of the circumstances of their discharge.

Additional factors may contribute to our finding that scheduling appointments was associated with successful care transitions for patients with low or no previous engagement in care. Some patients who previously had not engaged in care may have been affected by their current episode or circumstances in such a way that they became more motivated to seek outpatient care and collaborated with the inpatient treatment team on a discharge plan that included a scheduled appointment with an outpatient provider. Relatedly, for some patients, the inpatient treatment team may have accurately perceived other indicators that the patient was more likely to follow up and preferentially scheduled appointments for those individuals. We do not have data to address either of these possibilities.

Potential limitations to this study included the possibility that unmeasured variables, such as transportation constraints, may have affected attendance at outpatient appointments. We also relied on multiple MBHOs independently reporting provider discharge planning activities, creating significant potential for measurement error. Findings from a Medicaid population may not generalize to commercial or Medicare populations, and the New York State Medicaid population likely differs from other state Medicaid populations given variations in eligibility and enrollment practices across states. Additionally, the results are based on patients with 1 year of near-continuous Medicaid enrollment and may not generalize to those with shorter enrollment.

One may also question whether data regarding discharge planning practices from 2012–2013 reflect contemporary practice, given the impact of recent health care reforms related to the Affordable Care Act. We believe the findings reported herein remain highly relevant because of the paucity of quality measures for behavioral health and because 7- and 30-day follow-up after hospitalization for mental illness, which should be sensitive to discharge planning practices, remain among the most commonly used measures in quality and performance measurement programs. Published reports indicate that hospital ratings on these measures did not change appreciably from 2005 to 2015 despite implementation of multiple state and federal quality and value-based initiatives (

41,

42). Currently, publicly reported national average 7- and 30-day follow-up rates among Medicare recipients available online at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Hospital Compare website (

https://www.medicare.gov/care-compare/#search) are 27.7% and 49.4%, respectively. These continued low rates further underscore the need for heightened focus on discharge planning practices and care transitions in this population, making our findings highly relevant.