Efforts have been made worldwide to give mental health services a more recovery-oriented direction, by using a recovery-oriented practice as the dominant paradigm (

1–

3). In this paradigm, personal recovery is defined as “a way of living satisfying, hopeful, and reciprocal lives, together with others even though we may still experience distress. . . .” (

4). Personal recovery differs from clinical recovery, which has traditionally focused on the reduction of symptoms and increased levels of functioning (

5). Recently, a meta-analysis has found a significant small-to-medium association between clinical recovery and personal recovery, suggesting that both perspectives should be considered in treatment and outcome monitoring of patients with severe mental illness (

6). Nevertheless, the biomedical model continues to prevail in hospital-based mental health services (

1–

3). Thus, further development and implementation of recovery-oriented practices in these settings is warranted.

Peer support, defined as “giving and receiving help founded on key principles of respect, shared responsibility, and mutual agreement of what is helpful” (

7) delivered by individuals with lived experiences of mental illness, is regarded as a central element in recovery-oriented practices (

1,

8–

13). In the 1970s, peer support emerged in nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and in recent years, peer support has become widely used across different settings—for example, peers are employed as recovery mentors in psychiatric hospital health care, volunteer in mutual support groups in civil-society settings, and moderate online peer-to-peer interventions.

However, the evidence of the effectiveness of peer support is mixed and is primarily based on outcomes among individuals with severe mental illness. Little or no effect of peer support has been found on outcomes of clinical recovery, whereas a small positive effect has been identified on self-reported personal recovery of people with mental illness (

14–

17). Meta-analyses have revealed a modest effect of one-to-one peer support on personal recovery and empowerment (

18), and some evidence indicates that group peer support, mostly as self-management interventions, supports personal recovery (

19). No meta-analyses have been conducted on online peer support (

20) or, to our knowledge, on peers hired in established mental health professional roles. Nevertheless, the most recent reviews conclude that the evidence for the effectiveness of peer support interventions for people with mental illness is weak because of a persistent lack of high-quality studies (

17,

19).

A recent Cochrane review (

17) did not distinguish between clinical and personal recoveries but focused on global state of mental health, hospital admissions, and mortality rates as primary outcomes, even though peer support models do not intentionally address these clinical end points. In the present systematic review with a meta-analysis, our objective was therefore to build on and expand on previous reviews to update the evidence for the effectiveness of both face-to-face and online peer support. Peer support intends to promote experiences of personal recovery of individuals who are hospitalized or are experiencing ongoing psychiatric symptoms (

6). Therefore, we sought to investigate the effect of peer support primarily on personal recovery and secondly on clinical recovery of individuals with any mental illness.

Recently, the U.K. Medical Research Council has developed a framework that emphasizes the importance of context when evaluating complex interventions such as peer support (

21). In line with this guidance, it has been hypothesized that peer support provided independently of mental health–related hospital services may be better at maintaining the core values of peer support; such an approach provides “whole-life” mutual peer support rather than peer support provided within the mental health system, which is based on the practice, culture, and norms of psychiatric services in hospitals (

22). However, recent reviews have not examined whether the effect of peer support on recovery depends on the organizational context. Therefore, we also aimed to investigate the effect of four different types of peer support: peers added to hospital services, peers in established service roles, peers working independently of hospital services, and peers providing services online. We hypothesized that peer support offered independently of hospital settings might have a different effect on personal recovery than peer support provided within hospital services or as part of online programs.

Methods

A review protocol was developed by following PRISMA guidelines (

23). The review protocol is available in PROSPERO (CRD42018095583;

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=95583). The studies identified in literature searches (described below) were grouped into four organizational categories independently by two authors (C.H.E., S.S.M.). The studies were examined with a focus on the setting of the interventions and organization within or independent of mental health–related hospital services. In cases with uncertainties about service setting, online searches of the hospital or other institution in which the intervention took place were conducted, and study authors were contacted directly. Additionally, one author (L.F.E.) was consulted at in-person meetings, and the categorization of the studies was discussed until an agreement was reached.

Studies on peer services in a mental health hospital setting, including both inpatient and outpatient treatments, were placed in the category “peers added to hospital services” because peer services were offered in addition to standard mental health care; for example, recovery mentors were assigned a unique peer role. Studies with peers employed in established mental health positions were categorized as “peers in established service roles.” Peers in interventions not connected to (in- or outpatient) treatment in a hospital and deployed via a nonhospital organization such as an NGO, university research centers, community-based peer-run programs, self-help agencies, or crisis residential programs were placed in the category “peers independent of hospital services.” Peer support interventions provided online were placed in the category “peers online.”

Initially, we aimed to compare peer support interventions that included peer advocacy with interventions not including peer advocacy. However, this subgroup analysis was not possible because the descriptions of the interventions in the studies were not detailed enough to distinguish interventions that explicitly had a focus on peer advocacy from those not having this focus.

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

We conducted a comprehensive literature search in PubMed, PsycInfo, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science. The search strategy included terms related to or describing the intervention, the relevant patient groups, and methodological design. (The search terms are available in the

online supplement to this article.) Articles written in English, Danish, Norwegian, or Swedish published since 2000 were included. The initial search was conducted in April 2018, and an updated search was performed in June 2019. In addition, reference lists of the included studies, as well as of reviews, were searched and authors of published randomized controlled trial (RCT) protocols were contacted by e-mail for any unpublished results. All citations retrieved through the search were screened independently by three authors (C.H.E., S.S.M., M.N.N.) in Covidence (

24). The full texts were retrieved and independently assessed for eligibility (described below) by the same three authors. Disagreements were resolved through discussion with a fourth author (L.F.E.).

The included studies were approved by research ethics boards or committees of the study authors’ institutions and were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Inclusion Criteria

Participants.

Studies selected for inclusion were RCTs with adults (i.e., ages ≥18 years) who currently or previously had received in- or outpatient mental health care for any mental illness.

Intervention.

We included trials of interventions with peer support that were delivered either by peers only or by both mental health professionals and peers. Peers could be individuals who had lived experiences with mental illness and were working voluntarily or paid in a position specifically created for them or in an established professional position. We included a wide spectrum of peer interventions, ranging from peer support workers in mental health hospital care who were delivering services for individuals or in groups to peer support delivered in a variety of community settings or via online programs.

Comparison.

Studies employing treatment-as-usual, waitlist, or active control groups as comparison conditions were included in the meta-analysis. Some studies had multiple comparison groups; in such instances, the group with the peer support element was compared with the comparison group without the peer support element. In post hoc analyses, we included the remaining comparison groups.

Outcome.

If the studies reported on instruments measuring the broad concepts of personal recovery or clinical recovery, they were included in the meta-analysis. Primary outcomes included self-assessment scores from instruments measuring personal recovery. These instruments included the Mental Health Recovery Measure, the Questionnaire About the Process of Recovery, and the Recovery Assessment Scale (

25). Additionally, a wide range of questionnaires measuring constructs of hope, empowerment, self-efficacy, self-advocacy, stigma, network or social support, self-esteem, loneliness, and community were used. Secondary outcomes included clinician-rated and self-assessed outcomes determined with instruments measuring clinical recovery, including overall psychiatric symptoms assessed, for example, with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; symptom scales measuring depression, anxiety, and psychosis; levels of psychiatric disability and functioning; the Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation; and the 24-item Behavior and Symptom Identification Scale (BASIS-24). We also included general medical and mental health outcomes assessed, for example, with RAND 36- and 12-item Short Form surveys, as well as other outcomes such as quality of life and satisfaction with services and treatment. Each scale measuring an outcome was assessed by two authors (C.H.E., S.S.M.) to determine whether the scale was comparable to other scales measuring the same outcome. In cases where the scale was not measuring a comparable underlying construct, the outcome or scale was excluded from the meta-analysis.

Study Design

All published and available unpublished RCTs and cluster RCTs were eligible for inclusion.

Exclusion Criteria

We excluded studies on individuals with intellectual disabilities, psychosomatic disorders, sexual offenders, or forensic psychiatry. We also excluded studies with a primary focus on general medical illness, substance use disorder, or prevention or on relatives of individuals with mental illness.

Bias Risk Assessment

Risk for bias was assessed independently by four authors (C.H.E., S.S.M., L.H., M.N.N.) according to a modified Cochrane Collaboration tool (

26) that included the following aspects: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, power calculations, and intent to treat. Assessment of power calculation and intent to treat replaced the category “other” bias in the risk-of-bias tool. The item “blinding of participants and personnel” was not included in the assessment because of the nature of the peer support services, where the common understanding of lived experience is a vital component of peer models. The risk-for-bias assessment was converted to Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) standards (

27) to get an assessment of good quality (all criteria met low risk for bias for each domain), fair quality (one criterion not met, such as high risk for bias for one domain, or two criteria unclear and an assessment that this was unlikely to have biased the outcome, as well as absence of a known important limitation that could invalidate the results), and poor quality (two or more criteria categorized as high risk for bias or unclear risk for bias and an assessment that this was likely to have biased the outcome, as well as presence of important limitations that could invalidate the results).

Data Extraction

Data were extracted by two authors (C.H.E., S.S.M.) for the meta-analysis and summary of findings. Extracted information included study methodology, setting, results, and population; participant demographic characteristics; details of the intervention and control conditions; outcomes and times of measurement; descriptions of peers; and categorization of the peer intervention. Means±SDs for relevant outcomes at the end of the intervention were extracted for the meta-analysis, and missing data were requested from study authors.

Statistical Analysis

Comprehensive meta-analysis software (Biostat) was used for the statistical analysis. Pooled estimates at the end of an intervention were calculated as the standard mean difference (SMD) and 95% CIs in a random-effects meta-analysis design with inverse variance weights. The heterogeneity of study results was assessed through visual inspection of forest plots, the p value of the chi-square test, and the I

2 statistic (a descriptor of the variability in effect estimates due to heterogeneity rather than chance). A p<0.1 and I

2>50% suggest substantial heterogeneity. Funnel plots were used to visually inspect the risk for publication bias. The statistical significance level was set at p<0.05. Effect sizes were interpreted according to research guidelines (

28), and Cohen’s d effect sizes defined as small (Cohen’s d=0.2), medium (Cohen’s d=0.5), and large (Cohen’s d=0.8) were used as guidance (

28,

29). We included all studies with applicable data in the meta-analysis, and studies with treatment-as-usual and active control groups were analyzed together. One unpublished study included more than one eligible peer support intervention with applicable data (Miller R., personal e-mail communication, 2018). The data from the two interventions were pooled for the meta-analysis. In post hoc exploratory meta-analyses, we analyzed studies with peer-led peer support compared with clinician-led peer support, as well as co-led, one-to-one, and group-based peer support interventions compared with treatment-as-usual or active control groups.

Results

Trial Flow

The search resulted in 12,161 records; one unpublished record was identified by contacting an author to request a study protocol, and 119 records were found through hand searching of reference lists. After removal of duplicates, the titles and abstracts of 11,789 records were screened. After the screening, the full texts of 155 studies were assessed for eligibility, and 59 studies were included, reporting on findings in 49 RCTs (a flow diagram of the selection process is available in the online supplement). Of these, 34 reported data that could be used in the meta-analysis. The authors of the remaining 14 trials were contacted and asked to provide data. However, none of the authors provided applicable data for the meta-analysis; hence, these trials were included only in the narrative part of the systematic review results (below).

Systematic Review

Study characteristics.

The detailed characteristics and summary of findings of the included studies in this systematic review and meta-analysis are shown in the online supplement. The 49 RCTs involved 12,477 participants (range 15–1,827 participants per trial). In total, 32 trials were from the United States, four from Canada, four from the Netherlands, three from the United Kingdom, two from Norway, one from Germany, one from Switzerland, and one from Australia.

Participants and organization.

Most of the trials included in this review had adult participants with schizophrenia spectrum disorder, bipolar disorders, or major depression. Trials covering diagnoses of anxiety, depression, hoarding disorder, eating disorder, and suicidal ideation were also included. Twenty-six published trials (

30–

58) and one unpublished trial (Miller R., personal e-mail communication, 2018) evaluated peers added to hospital services and 39.0% (N=4,863) of the participants. Three trials (

59–

62) evaluated peers in established service roles and included 2.4% (N=297) of the participants. Thirteen trials (

63–

79) evaluated peers independent of hospital services and 40.4% (N=5,036) of the participants. Last, five trials (

80–

87) evaluated peers online and included 18.3% (2,281) of the participants.

Interventions.

The four categories of peer support each contained a very broad variety of peer-facilitated interventions or services (see table in the

online supplement). For example, the category “peers added to hospital services” included recovery mentors delivering one-to-one peer support or group-based, peer-led self-management programs such as the Health and Recovery Peer (HARP) (

56) and Illness Management and Recovery (

48) programs, as well as self-help groups (

42,

52) and peer specialists who are part of case management teams (

53,

55). The category “peers in established service roles” comprised interventions employing paid peers facilitating one-to-one conversations about requests for treatment (

59), assertive community treatment (

60,

61), and occupational rehabilitation goals (

62).

The category “peers independent of hospital services” included peer-designed interventions such as the Wellness Recovery Action Planning (WRAP) (

63,

64,

72) and Building Recovery and Individual Dreams and Goals Through Education and Support (BRIDGES) (

73,

74) and peer-led but researcher-designed interventions such as Coming Out Proud (

75), naturally occurring peer support in peer-run organizations, and self-help agencies. Four trials evaluating “peers online” comprised unmoderated and moderated online mutual support groups (

80–

87). Trials varied in the length of the intervention from one 4-hour session (

37) to 2-year interventions (

31,

48); the average intervention length was about 6 months. Thirteen interventions were delivered from a manualized protocol. We identified nine trials evaluating interventions with a focus on self-advocacy (

35,

54,

55,

68–

70,

72,

74) (Miller R., personal e-mail communication, 2018). However, the depth, content, and fidelity of the interventions, as well as the peer training, were not always reported in detail.

Control Conditions

Peer support interventions were compared with treatment as usual in 25 trials (

30,

32,

36,

37,

39,

40,

43–

45,

47–

50,

53–

57,

60–

62,

66,

68–

70,

76,

78) (Miller R., personal e-mail communication, 2018) and waitlist control conditions in nine trials (

31,

33,

42,

51,

52,

63,

64,

67,

73,

74,

80–

82); five trials (

34,

41,

59,

75,

79) had active control conditions such as nonpeer group counseling, clinician-led psychiatric advanced directives, and cognitive-behavioral therapy. The remaining eight trials (

38,

46,

58,

65,

77,

83–

87) were three- or four-armed trials with treatment-as-usual and active control groups (see table in the

online supplement).

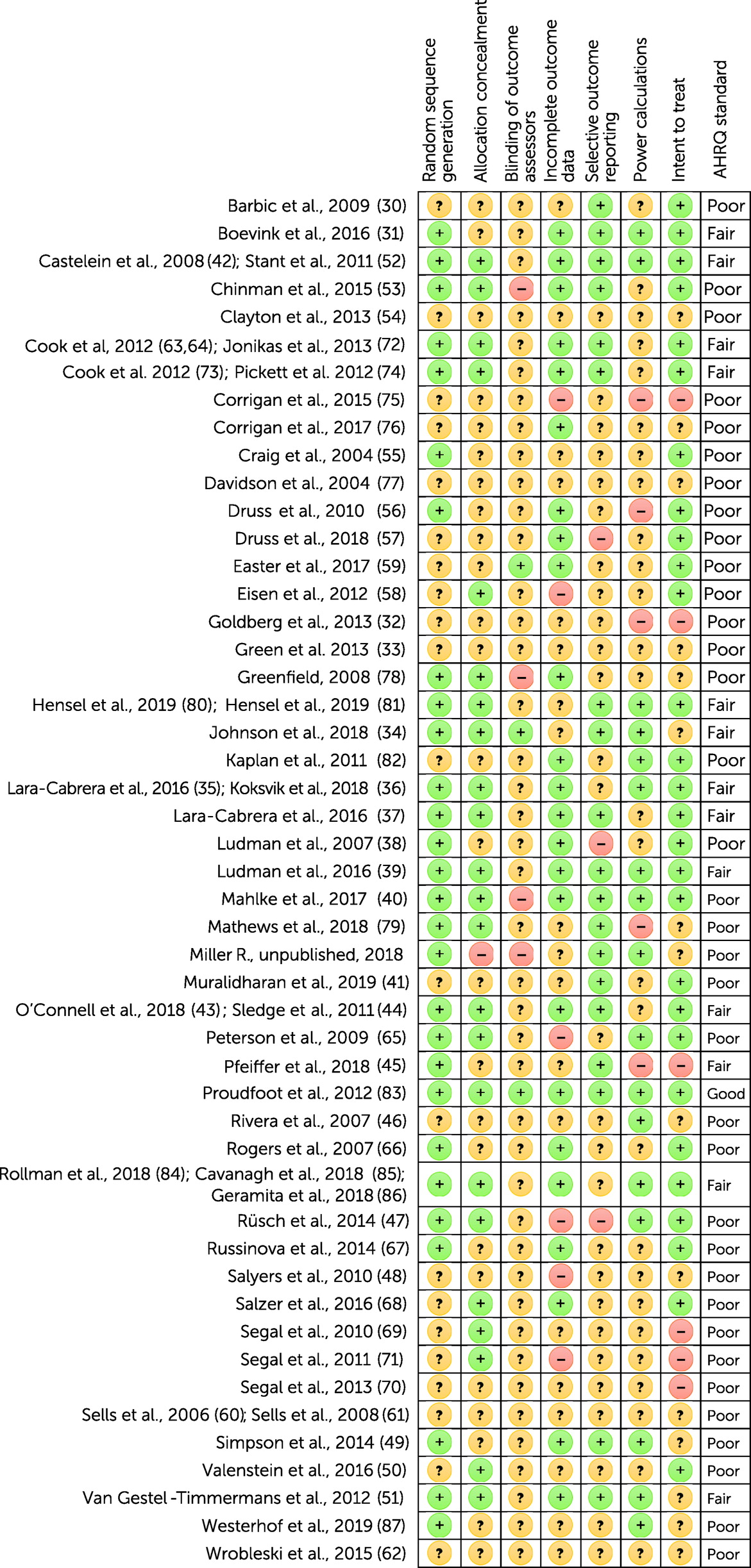

Risk for Bias

The included RCTs were characterized by high or unclear risk for bias in many domains of the modified Cochrane risk-of-bias tool checklist (

Figure 1). According to AHRQ standards (

27), nine of the trials in the “peers added to hospital services” category (

31,

34–

37,

39,

42–

45,

51) were of fair quality, and 18 trials (

30,

32,

33,

38,

40,

41,

46–

50,

52–

57) (Miller R., personal e-mail communication, 2018) were of poor quality. In the category “peers independent of hospital services,” two trials (

63,

64,

72–

74) were of fair quality, and 11 trials were of poor quality (

65–

70,

75–

79). In the “peers in established service roles” category, all three trials (

59–

62) were of poor quality. The “peers online” category consisted of one trial (

83) that had no risk for bias in all domains and two trials of fair quality (

80,

81,

84–

86) and two trials of poor quality (

82,

87).

Meta-Analysis

Pooled effect sizes for personal and clinical recovery outcomes at the end of interventions are presented in the online supplement. If only one trial reported on an outcome, a pooled effect size was not applicable.

Peer support in general.

Pooled effect sizes for the “peer support in general” category are presented in the

online supplement. Results from 11 trials of poor quality (

30,

32,

50,

53,

57,

58,

67,

68,

77,

82) and six trials of fair quality (

34,

39,

52,

63,

64,

72–

74,

81) with significant but moderate heterogeneity across studies revealed that peer support in general had a small positive effect on personal recovery (SMD=0.20, 95% CI=0.11–0.29, p<0.001; I

2=47%, p=0.02, N=4,104), compared with treatment-as-usual, waitlist, or active control groups. Results from eight trials of poor or fair quality with no indications of heterogeneity (

30,

45,

48,

51,

58,

63,

64,

72–

74) (Miller R., personal e-mail communication, 2018) indicated that peer support had a modest positive effect on hope compared with treatment-as-usual or waitlist control groups (SMD=0.12, 95% CI=0.02–0.22, p=0.015; I

2=0%, p=0.6, N=1,642), and results from two trials of fair quality with no indications of heterogeneity (

72,

74) disclosed a modest effect of peer support on self-advocacy compared with waitlist control groups (SMD=0.17, 95% CI=0.03–0.31, p=0.02; I

2=0%, p=0.7, N=800). No significant effects of peer support on empowerment, loneliness, self-efficacy, self-esteem, or network or social support were observed. Measuring a pooled effect size for community was not applicable because of insufficient data.

Regarding outcomes related to clinical recovery, findings from two trials of fair quality (

73,

80,

81) and two trials of poor quality (

78,

79) with significant substantial heterogeneity indicated that peer support had a small effect on reducing anxiety (SMD=−0.21, 95% CI=−0.40 to −0.02, p=0.03; I

2=68%, p=0.03, N=1,400), compared with treatment-as-usual, waitlist, or active control groups. No significant effects of general peer support on overall psychiatric symptoms, psychotic symptoms, depression, suicidal ideation, BASIS-24 score, and self-reported health, as well as quality of life and satisfaction with services, were observed. Measuring a pooled effect size for level of functioning was not applicable because of insufficient data.

Peers added to hospital services.

Pooled effect sizes of the category “peers added to hospital services” are presented in the

online supplement. Regarding main outcomes related to personal recovery, seven trials of poor quality (

30,

32,

41,

50,

53,

57,

58) and three trials of fair quality (

34,

39,

52) with significant moderate heterogeneity reported that peers added to hospital services had a small positive effect on personal recovery compared with treatment-as-usual, waitlist, or active control groups (SMD=0.22, 95% CI=0.09–0.34, p<0.001; I

2=49%, p=0.04, N=2,230), and results from three trials of poor quality with no significant heterogeneity (

32,

40,

41) revealed that such peers had a small-to-medium positive effect on self-efficacy (SMD=0.36, 95% CI=0.09–0.62, p=0.008; I

2=39%, p=0.2, N=407), compared with treatment-as-usual or active control groups. Findings from four trials of poor quality (

30,

48,

58) (Miller R., personal e-mail communication, 2018) and two trials of fair quality (

51,

57) with no indications of heterogeneity indicated that adding peers to hospital services had a modest effect on hope (SMD=0.16, 95% CI=0.02–0.29, p=0.03; I

2=0%, p=0.4, N=853), compared with treatment-as-usual or waitlist control groups. No significant effects of peers added to hospital services on empowerment, loneliness, self-esteem, or network or social support were observed. No studies reported outcomes related to self-advocacy, community, and stigma.

Regarding outcomes related to clinical recovery, two trials of poor (

52) or fair (

41) quality with no indications of heterogeneity reported that adding peers to hospital services had a small effect on reduction of overall psychiatric symptoms (SMD=−0.22, 95% CI=−0.40 to −0.04, p=0.02; I

2=0%, p=0.3, N=480), compared with a treatment-as-usual or an active control group, respectively. Adding peers to hospital services had no significant effects on depression, suicidal ideation, or self-reported health, as well as quality of life and satisfaction with services. No studies reported outcomes related to anxiety, BASIS-24 score, and level of function. Measuring a pooled effect size for psychotic symptoms was not applicable because of insufficient data for this category.

Peers in established service roles.

We found three trials that evaluated “peers in established service roles,” such as peers employed in established traditional mental health care positions instead of, for example, a nurse or case manager (

59–

62). However, none of the studies reported outcome data on personal and clinical recovery that could be included in this meta-analysis.

Peers independent of hospital services.

Pooled effect sizes for the category “peers independent of hospital services” are presented in the

online supplement. Regarding main outcomes related to personal recovery, findings from two trials with fair quality with no indications of heterogeneity (

72,

74) indicated that peers who provided support independent of hospital services had a modest positive effect on self-advocacy (SMD=0.17, 95% CI=0.03–0.31, p=0.02; I

2=0%, p=0.7, N=800), compared with waitlist control groups. No significant effects of these peers on outcomes of personal recovery, hope, empowerment, self-efficacy, self-esteem, and stigma were observed. No studies reported on outcomes related to loneliness or network or social support. Measuring a pooled effect size for community was not applicable because of insufficient data for this category.

Regarding outcomes related to clinical recovery, peers who provided support independent of hospital services had no significant effects on overall psychiatric symptoms, depression, and anxiety. No studies reported on outcomes related to suicidal ideation, BASIS-24 score, self-reported health, or satisfaction with services. Measuring pooled effect sizes for psychotic symptoms, level of functioning, and quality of life was not applicable because of insufficient data for this category.

Peers online.

Pooled effect sizes for the “peers online” category are presented in the

online supplement. Results of two trials of poor or fair quality with substantial heterogeneity (

80,

82) indicated that peers providing services online had a small and nonsignificant effect on personal recovery (SMD=0.27, 95%=−0.02 to 0.56, p=0.07; I

2=72%, p=0.07, N=746), compared with waitlist control groups. Results from two poor-quality trials with no indications of heterogeneity (

82,

87) indicated a small and nonsignificant effect of peers providing services online on network or social support (SMD=0.19, 95% CI=−0.04 to 0.41, p=0.11; I

2=0%, p=0.7, N=339), compared with waitlist control groups. No studies reported on the effects of online peer services on hope, self-efficacy, self-advocacy, self-esteem, and stigma. Measuring pooled effect sizes for empowerment, loneliness, and community was not applicable because of insufficient data for this category.

Regarding clinical recovery outcomes, findings from two trials of poor or fair quality and considerable heterogeneity (

80,

81,

87) indicated that online peer services resulted in a modest but nonsignificant decrease in depression (SMD=−0.14, 95% CI=−0.79 to 0.50, p=0.67; I

2=75%, p=0.05, N=485), compared with waitlist control groups. Measuring a pooled effect size for anxiety was not applicable because of insufficient data for this category. No studies reported on the effects of online peer services on overall psychiatric symptoms, psychotic symptoms, suicidal ideation, BASIS-24 score, function, self-reported health, and satisfaction with services. No significant effect of these services on quality of life was observed.

Heterogeneity

Detailed information on the heterogeneity of the studies included in the meta-analysis is presented in the online supplement. We included 34 trials in this meta-analysis investigating outcomes of personal and clinical recovery. Of the 47 analyses conducted, 20 had a high heterogeneity as indicated by I2>50% and p<0.1.

Publication Bias

Funnel plots were created for visual inspection of publication bias in the included studies (see the online supplement). Few of the analyses included ≥ 10 studies. However, several of the funnel plots indicated a risk for publication bias.

Post Hoc Analysis

Post hoc subgroup analysis was carried out to explore any potential differences in pooled effect sizes in one-to-one and group-based peer support, respectively. Additionally, post hoc analyses of co-led peer support versus treatment as usual and peer-led versus clinician-led peer support, as well as analyses excluding interventions without an explicit aim of personal recovery, were conducted (see table in the online supplement). No clear differences between one-to-one and group-based peer support in personal or clinical recovery outcomes were observed. Co-led peer support added to hospital services had statistically significant moderate effects on both personal and clinical recovery outcomes, compared with treatment as usual. Additionally, a significant moderate effect on social network and a small increase in depression symptoms was observed in peer-led versus clinician-led interventions. Last, post hoc analyses of interventions that explicitly aimed to improve personal recovery indicated that peers added to hospital services slightly decreased personal recovery compared with treatment-as-usual, waitlist, or active control groups.

Discussion

Main Findings

The findings of this systematic review and meta-analysis, comprising 12,477 participants in 49 trials, provide evidence that peer support targeting individuals with any mental illness has small effects on outcomes related to personal recovery and little or no effect on clinical recovery—although we did find a small reducing effect on anxiety symptoms. We found that peers employed and trained in supporting roles in the mental health hospital treatment service had a small positive effect on personal recovery, had a small-to-moderate positive effect on self-efficacy, and were associated with a small reduction in overall psychiatric symptoms. Additionally, we found that peer support delivered in peer-designed or cocreated interventions developed independently of hospital settings and provided in community settings had a modest positive effect on self-advocacy. We had no analyzable data on peers employed in established service positions. We also found that peer support delivered online had a small but nonsignificant positive effect on personal recovery. These results indicate that peer support might have an impact on different aspects of personal recovery that reflect the core values of peer support provided in different organizational settings. However, more high-quality RCT studies coproduced by clinicians, researchers, and peer supporters, especially of peers working independently of hospital services or in online settings, are needed to further contribute to the literature on the efficacy of peer support in mental health care.

Comparison With Earlier Review Findings

The findings that peer support has small positive effects on personal recovery and little or no effect on clinical recovery in poor-to-fair-quality trials with high heterogeneity are consistent with previous findings of reviews evaluating peer support for individuals with severe mental illness (

15–

17). The present review adds evidence that the positive effects of peer services on personal recovery and decreased psychiatric symptoms occur across different diagnostic categories of mental illness. Additionally, and contrary to our initial hypothesis, the effect on personal recovery was most evident in peer support delivered as and as an add-on to standard mental health treatment in hospital services. Still, our findings support observations in previous reviews that the evidence of peer support is weak given a lack of high-quality studies (

17). Previous meta-analyses have shown small positive effects of peer support on outcomes such as personal recovery, hope, and empowerment (

15–

17). In the present meta-analysis, we excluded data on empowerment from one trial (

30) because of very large inconsistencies in the data; this exclusion may partly explain why we did not confirm previous findings of a positive effect of peer support on empowerment. Moreover, differences in time of data extraction at the end of an intervention or at follow-up, along with differences in categorizing trials in different organizational settings across the studies in this review and previous reviews (

15,

16), may also have had an impact on the comparison of findings across studies.

Peer Support Setting and Approach

We found that the effect on improved personal recovery was most pronounced for peers added to hospital services compared with other peer categories. One explanation for this finding is that peers added to established mental health services is the most effective form of peer support. However, hospital services have a longer tradition of conducting RCTs, possibly explaining why this category included most of the effective trials of reasonable quality compared with the other categories. For instance, the authors of a recent review (

20) concluded that online peer support interventions have potential but are in the early stages of development and require well-powered clinical trials, in line with our finding of a small and nonsignificant effect of online peer support on personal recovery. Moreover, it has been posited that recent trials indicating effectiveness of peer support in the established mental health services likely evaluated some form of peer-supported individual self-management rather than more mutual peer support. That is, individuals are supported in their recovery by peers who provide skills and confidence that enable service clients to manage their own health problems, rather than by an approach in which the recipient and the peer support provider mutually support and help each other (

88). We also note that the focus in the field has shifted to primary outcomes related to individual empowerment and advocacy (

18,

89), such as peer support facilitating a belief about the ability to exert control over one’s own life by learning to communicate and advocate for one’s own needs.

Peer-designed or cocreated interventions such as WRAP or BRIDGES were developed to be provided independently of mental health hospital care, and we found that these interventions have a modest positive effect on self-advocacy. Nevertheless, it has been argued that these peer support approaches belong to a traditional medical model of mental health, in which peer workers operate in complementary functions by enabling clients to cope better with mental health problems (

22). We found no applicable data for peers in established service roles, in line with a recent review noting that most of the studies comparing peer workers with other mental health workers performing a similar role were published >10 years ago; none of them included data on personal and clinical recoveries (

18), suggesting that employing peers in established clinical functions is outdated.

Because peer support is a complex intervention, we recommend that qualitative studies better capture the needs, active ingredients, and mechanisms of change experienced by peer support providers and recipients (

8,

19,

21). Some qualitative studies have reported that identification with a role model and the building of trusting relationships based on shared experiences are key mechanisms to increase empowerment, self-efficacy, and social function (

90). Additionally, future interventions should be transparent about the type of peer support approach used. These approaches may include trauma-informed interventions with a focus on what has happened in a client’s “whole life,” rather than illness-focused approaches centered on symptoms and disabilities (

91); intentional peer support with a focus on equal power relationships and reciprocal roles of helping and learning with a focus on community rather than individual change alone (

92); and a peer-supported individual self-management approach (

34).

We note that it is important to state whether peers are employed as paid staff or volunteers, because a peer’s role and position may have an impact on the mechanisms of the intervention. Accordingly, to secure the active ingredients of peer support, we recommend that future interventions should be developed and evaluated via a cocreation approach that involves peers on an equal footing with researchers, taking advantage of peers’ lived experiences (

9,

19,

22). This tactic should include the development of a program theory based on a clear description of the theory of change and a hypothesis about proposed mechanisms of any effects (

18,

19,

93); this knowledge could inform high-quality RCTs and the development of fidelity measures, along with both quasi-experimental and process evaluations. Moreover, it has been noted that the journey of personal recovery is gradual (

94), emphasizing why longitudinal intervention measurement is recommended. Furthermore, we recommend that identification of factors that hinder or promote implementation should be prioritized (

8), and we also note that cost-effectiveness studies of peer support interventions are needed (

18,

19).

Peer Support Provider and Type

Results of post hoc explorative analyses revealed that interventions that were co-led by a mental health professional and a peer provider had significant positive effects on measures of both personal recovery and clinical recovery (see tables in the

online supplement). These findings were in agreement with results from a meta-analysis by Thomas et al. (

95), showing that co-led interventions yielded the greatest effects on recovery compared with control groups. These findings suggest that partnership and collaboration between mental health professionals and peers enhance recovery. A qualitative review has indicated that clinicians working with peer support workers gained increased belief that recovery from mental illness is possible (

96). In additional post hoc analyses, we confirmed recent findings that one-to-one peer support added to hospital services has a small but significant impact on personal recovery (

18). Moreover, we confirmed findings that group-based peer support has a modest impact on personal recovery (

19), suggesting that this impact may be independent of whether peer support is delivered in an individual or group format. Last, we showed that exclusion of interventions without an explicit aim of personal recovery, such as the HARP program (

57) and Living Well (

32), slightly decreases effects on personal recovery, indicating that although the programs did not explicitly aim to aid personal recovery, they still improved recovery. Nevertheless, further high-quality studies with a focus on peer support delivery and type of peer support in different organizational settings are needed to confirm these explorative findings.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this study included the distinction between personal and clinical recovery outcomes and division into different types of peer support. We included a wide spectrum of peer support interventions, allowing for subgroup analyses of clinician-led versus peer-led, co-led, one-to-one, and group-based peer support. The first author of this review has lived experience of mental illness and as a peer-group facilitator, which was a strength in the operationalization of peer support, as well as in the interpretation of the implications of findings. The findings are generalizable to adult mental health hospital practice, independent community settings, and online platforms, primarily across samples in the United States but also in Europe. Nevertheless, the generalizability of the findings is primarily restricted to populations from Western countries.

Limitations included the poor quality of several of the reviewed studies, a generally high heterogeneity across the studies, and inadequate descriptions of intervention settings. Additionally, the definition of peer support is very challenging because of differences in health care system delivery and organization across countries, as well as a lack of transparency about intervention content, peer recruitment, training, and supervision. Especially the category “peers independent of hospital services” contained very disparate types of interventions where the only common feature was that they are peer-facilitated interventions or services in nonhospital organizations. The results of the meta-analyses of this category should therefore be interpreted with great caution, and the nonsignificant effect on personal recovery could be explained by the differences between the interventions compared. However, all interventions had an overall aim of improving personal recovery and were therefore pooled in the meta-analyses, which underlines the complexity of the field exploring the effectiveness of the peer element across a broad variety of interventions. None of the studies included measures of attrition among the peer support providers or potential worsening adverse effects among clients.

Several of the funnel plots indicated a risk for publication bias in the studies examined. Risk for bias included lack of transparency in randomization, insufficient blinding of outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, and selective reporting, increasing the risk for selection and detection bias. Additionally, all trials had high risk for bias for the item “blinding of participants and personnel” because of the nature of the peer support intervention, increasing the risk for expectancy and performance bias. Nevertheless, we do not expect peer service research to overcome this limitation, because the building of safe relationships based on exchange of lived experiences is a vital component of peer models. Other limitations included the fact that studies with treatment-as-usual and active control groups were analyzed together, heterogeneity in study procedures such as group and individual format, and varying duration of peer support services. We addressed some of these limitations in post hoc subgroup analyses. Further post hoc analyses of the content and the length of intervention, manualized versus nonmanualized delivery, and volunteer versus paid peers were considered but were not possible because of inadequate descriptions of the interventions. Also, this meta-analysis evaluated the addition of peer support to highly varied standard services. Finally, we conducted several separate meta-analyses in this review, increasing the risk for type 1 error.

Conclusions

We found evidence that peer support interventions generally but only slightly improve outcomes of personal recovery and slightly reduce symptoms of anxiety among individuals with any mental illness. The effect of peer support on personal recovery was most pronounced in peer support delivered as an add-on to mental health hospital treatment. However, the evidence for the efficacy of peer support provided independently of hospital settings and online is promising and requires more high-quality RCTs and attention from policy makers and funders. Nevertheless, before we can recommend implementation of peer support in specific health care settings, cocreated high-quality trials measuring the effectiveness, including potential adverse effects, and the cost-effectiveness of the intervention are needed. Moreover, a lack of consensus about delivery and the active ingredients of peer support highlights why transparency about the choice of peer support type, the content of the manual, peer education, and fidelity assessments should be described thoroughly in future trials. Therefore, qualitative studies are needed that investigate the mechanisms of change in mutual peer support relationships, evaluate the best methods for implementing peer support interventions, and assess the collaboration between mental health professionals and peers.