Each year in the United States, one in 25 adults experiences a serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or other psychotic disorders (

1), resulting in an estimated earnings loss of $193.2 billion (

2). About 7.7% of adults ages 18–25 years and 5.9% of those ages 26–49 years have a serious mental illness (

1). Since the advent of the deinstitutionalization movement, dramatic depopulation and closing of state psychiatric hospitals have occurred, with the aim of fostering community integration (

3). A significant proportion of individuals with serious mental illness continue to live in facilities that are considered institutions, such as nursing homes (

3).

In the United States, nursing homes are primarily designed to care for older adults with cognitive and physical limitations, rather than providing the specialized care that persons with severe psychiatric illness need. Nevertheless, many people with serious mental illness reside in nursing homes. As of 2004, approximately 13% of nursing home residents had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, and 4% had a diagnosis of bipolar disorder (

4); however, more recent data are unavailable (

5). About 2% of persons of all ages with serious mental illness resided in nursing homes between 2008 and 2009 (

3). Working-age adults with serious mental illness may represent a growing population of nursing home residents with unique care needs. In 2015, 16.5% of U.S. nursing home residents were ages <65 years (

6). Although this age group may account for nearly half of all people with serious mental illness admitted to nursing homes (

7), research on the psychiatric care needs of these residents is sparse.

Individuals with serious mental illness are more likely to be admitted to lower-quality nursing homes (

8–

11). To our knowledge, among studies examining nursing home quality for residents with serious mental illness, only one has examined residents younger than 65 years (

8). To address this knowledge gap, we sought to explore the association between nursing home quality and the presence of serious mental illness (i.e., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or other psychotic disorders) among working-age adults (ages 22–64 years) admitted to a nursing home.

Methods

Study Design and Data Sources

This was a cross-sectional study approved by the institutional review board of the University of Massachusetts Medical School. The Minimum Data Set (MDS) 3.0 is a government-mandated assessment of residents in Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS)–certified nursing homes in the United States (

12). It is completed for each resident by nursing home staff and the resident at admission, quarterly, and when health changes occur. Assessments include demographic, clinical, cognitive, and functional characteristics and receipt of pharmacological and nonpharmacological therapies. MDS 3.0 2015 data were merged with CMS’s five-star quality rating system, Nursing Home Compare (NHC) (

13). NHC rates nursing homes with one to five stars across four domains: health inspections, staffing, quality of care, and overall. Ratings are calculated by using facility characteristics, such as number and severity of deficiencies, staffing hours, and percentage of residents whose function improves. MDS 3.0 admission assessments were merged with the most recent quarterly NHC data at resident admission date by using CMS certification number.

Eligibility Criteria

Residents ages 22–64 years (i.e., working-age adults) newly admitted to a nursing home in 2015 were included (see flowchart in the

online supplement to this article). Admission was determined by using the CMS definition (

12) (see

online supplement for MDS item numbers). Thus, residents admitted after acute care were not included. A new admission was further defined by excluding those who were admitted from another nursing home or swing bed or who had a previous nursing home stay within 90 days of admission assessment. When more than one admission assessment was conducted, we randomly selected one for analysis. We excluded those without an NHC match (N=1,700), comatose residents (N=1,174), and those with missing information on key variables (N=39,822). The final sample included 343,783 persons and 14,307 facilities.

Outcome Measure

The outcome measure was a binary indicator of serious mental illness defined as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or other psychotic disorder (see

online supplement for MDS item numbers) (

7). A diagnosis is recorded in MDS if it is documented by a physician and directly affects the resident’s health or medical treatments (

12).

Exposure Measure

The key exposure was whether a nursing home was of below-average quality, as measured by the health inspection domain of the NHC star ratings. One star indicates quality that is much below average, three stars indicate average quality, and five stars indicate quality much above average (

13). The health inspection rating is based on federal regulations, is a standardized survey process, uses the 3 most recent years of inspections, and is weighted by the scope, severity, and timing of deficiencies (

13). Major metrics for evaluating quality of care are incorporated, including staffing, nursing home environment, medication management, and resident quality of life (

13–

15), and the NHC rating moderately correlates with consumer ratings (

16). The distribution of the health inspection rating is set so that for every state, 10% of nursing homes receive five stars, 20% receive one star, and the remaining facilities are distributed evenly across the other categories (

13). Although the number of star ratings is based on the number of nursing homes in a state, the number of residents across these nursing homes is unknown and likely influenced by many factors. It is important to understand how many residents receive care in below-average facilities.

Covariate Measures

Sociodemographic (age, sex, race-ethnicity, marital status, and admission type), functional (activities of daily living and cognitive impairment), and clinical (psychiatric and other) covariates were obtained from the MDS admission assessment.

Age was categorized into four groups (22–34, 35–44, 45–54, and 55–64 years), and sex included male and female. Race-ethnicity categories were limited to non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and a composite category including American Indian, Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, or multiracial. Marital status included never married, married, widowed, and separated or divorced. Admission type included community (private home or apartment, board-and-care home, assisted living, or group home), acute hospital, psychiatric hospital, and other (inpatient rehabilitation facility, intellectual or developmental disability facility, or hospice).

Physical function included three levels (independent or limited assistance required, extensive assistance required, and dependent or totally dependent) as defined by using the Activities of Daily Living Self-Performance Hierarchy Scale (

17). The Cognitive Function Scale indicated intact cognitive function or mild, moderate, or severe impairment (

18). A set of binary variables for the presence of other active disorders was included (dementia or Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, neurological other than dementia or Alzheimer’s disease, pulmonary, cancer, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, infection, malnutrition, depression, anxiety disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder).

Nursing home structural characteristics (urban or rural location, ownership, and number of CMS-certified beds) were defined by using NHC data. Location was defined via the Census Bureau’s urban-rural classification system (

19). Ownership type included for profit, government, or nonprofit as designated in NHC. The number of certified beds was categorized into quartiles (<63, 63–99, 100–127, and ≥128 beds). None of the covariates examined contributed to the health inspection star rating.

Statistical Analysis

We described the sample and facility-level characteristics by using data collected on individual residents, stratified by serious mental illness. We considered an absolute difference of ≥5% notable and used this measure rather than statistical significance because of the large sample size. We quantified the association between quality of nursing home and presence of serious mental illness by using a logistic mixed-effects model. The model included two levels: the individual level and the random effects of facilities. Dementia and neurological conditions were excluded because of multicollinearity. Covariates were included on the basis of clinical significance and previous studies (

8,

9). State cluster effect was accounted for by using state dummy variables to control for variations in health inspection surveying and policies related to mental health. Variations in health inspection surveying may occur because of differences in state licensing laws, variations in the survey process by state surveyors, and Medicaid policies that affect nursing home eligibility rules, payment, and enforcement of quality (

13).

Conceptually, the outcome could be the quality rating of the nursing home chosen by the resident. Fitting a model on a group-level outcome (i.e., the quality rating) with aggregated individual-level exposure and confounders but without accounting for individual-level variabilities may introduce bias (

20). To overcome this micro-macro multilevel situation, we defined the outcome as a binary indicator of serious mental illness (i.e., individual level) and the primary exposure as nursing home quality (i.e., group level) and fitted a logistic mixed-effects model to explore the association between nursing home quality and presence of serious mental illness while adjusting for individual-level covariates and similarity in the individuals’ nursing homes. The adjusted exposure odds ratio (OR) for the presence of serious mental illness is the same as the adjusted outcome OR for nursing home quality (

21).

We first ran an empty model with the outcome and facility-level random effects, then sequentially added the individual-level fixed effects, the facility-level fixed effects, and state dummy variables. The final model included all covariates listed in

Tables 1 and

2 (other than dementia and neurological conditions), state dummy variables, and random effects of facilities. We present adjusted ORs (AORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the full model, focusing on the primary exposure in

Table 1. (For full model results, see table in

online supplement.) We report the variance partition correlation coefficient (VPC) of the final model to examine the variation attributed to unobserved differences among nursing homes. SAS, version 9.4, software was used for these analyses.

Results

Of 343,783 working-age adults admitted to a nursing home in 2015, 66.3% (N=227,962) were between the ages of 55 and 64, 50.3% (N=172,884) were male, and 68.0% (N=233,750) were non-Hispanic White. Of this total sample, 15.5% (N=53,104) had a documented active serious mental illness diagnosis. Of the 14,307 nursing homes identified, 76.8% (N=10,987) were in an urban setting, 81.4% (N=11,641) were for profit, and 44.8% (N=6,409) had ≥128 beds. About one-quarter of nursing homes (N=3,874, 27.1%) had no working-age residents with serious mental illness; a higher percentage of these nursing homes were rural, smaller, and had nonprofit ownership and slightly higher health inspection ratings.

Characteristics of Working-Age Residents With Serious Mental Illness

As shown in

Table 1, 15.5% of residents with serious mental illness were married, compared with 30.5% of working-age residents without serious mental illness. Few residents (<1%) without serious mental illness were admitted from a psychiatric hospital, but 8.7% of residents with serious mental illness were. Residents with serious mental illness were less likely to have physical functional dependencies (37.9% required only limited assistance, compared with 25.3% of those without serious mental illness), and the proportion with intact cognitive function was smaller than among those without serious mental illness (66.3% vs. 76.6%). In the full sample, only a small percentage of the working-age residents (about 3%) had severe cognitive impairment or dementia or Alzheimer’s disease (residents with serious mental illness, 8.8%; residents without, 3.9%).

Clinical comorbid conditions of working-age adults tended to be similar among those with or without serious mental illness. More than half had hypertension, and significant proportions of the two samples (42.0%–50.8%) had cardiovascular disorders. One-third of those with serious mental illness had pulmonary disorders, compared with about one-quarter of those without. Depression and anxiety disorder were common but more frequent among those with serious mental illness (depression, 44.2% vs. 35.8%; anxiety disorder, 36.8% vs. 23.4%).

Serious Mental Illness, Facility Characteristics, and Quality of Nursing Home

The proportion of residents with serious mental illness in for-profit facilities was 6.1 percentage points higher than the proportion of residents without serious mental illness in these facilities (

Table 2). No meaningful differences by the presence of serious mental illness were observed in location and number of beds.

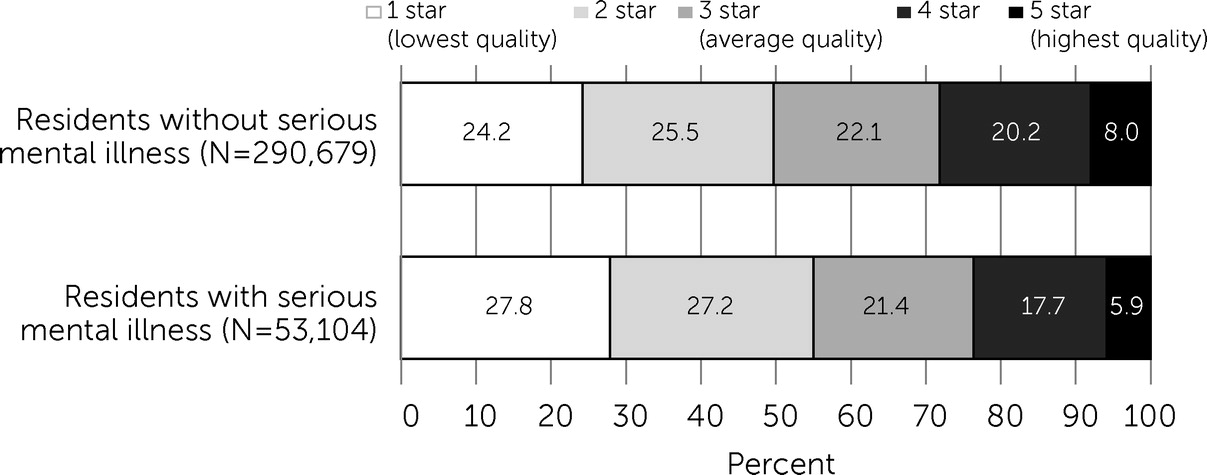

Figure 1 shows the proportions of persons in both groups residing in the five quality-ranked facility categories. Of residents with serious mental illness, 55.0% resided in nursing homes that received below-average quality ratings (one or two stars), compared with 49.7% of those without serious mental illness. Only 23.6% of residents with serious mental illness resided in nursing homes that received above-average quality ratings (four or five stars), compared with 28.2% of residents without serious mental illness.

Compared with a resident in a one-star nursing home, a resident in a five-star facility was significantly less likely to have serious mental illness (AOR=0.78), after the analysis was adjusted for individual- and facility-level covariates, state variations, and clustering in the nursing home (

Table 3). A similar trend was seen for nursing homes with four stars (AOR=0.85), three stars (AOR=0.90), and two stars (AOR=0.95) (see

online supplement for full model results). In total, 11% of the variation in the outcome was attributable to unobserved differences between nursing homes, after the analysis accounted for individual-level and facility-level covariates and state dummy variables (VPC=0.11).

Discussion

Our findings show that working-age residents with serious mental illness may experience a disparity in nursing home quality, compared with those without serious mental illness. Slightly more than half (55.0%) of working-age residents with serious mental illness were admitted to one- or two-star nursing homes. Furthermore, among newly admitted working-age residents, we found an association between having serious mental illness and below-average nursing home quality, after the analysis was adjusted for individual- and facility-level factors.

Persons with serious mental illness represent a disenfranchised population, and experts have called for serious mental illness to be designated as a health disparity (

22). Individuals with serious mental illness experience more than double the risk for early death, compared with the general population (

23,

24). Marginalized groups, such as persons from racial-ethnic minority groups (

25), individuals with low education status (

26), and persons dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid (

27), tend to reside in lower-quality nursing homes. In 2015, 26% of persons with serious mental illness were covered by Medicaid (

28), the predominant payer for nursing home care. The use of federal Medicaid funds for persons ages 22–64 years to receive care in specialized psychiatric facilities is prohibited, potentially incentivizing nursing home admission (

29,

30). Our analysis has shown that working-age residents with serious mental illness are at risk for receiving below-average nursing home care. Nursing homes with a high concentration of residents with serious mental illness have worse facilitywide outcomes (e.g., use of physical restraints, any hospitalization, and use of an indwelling catheter) (

11). Nursing homes often lack the resources and trained staff to treat persons with complex mental disorders (

31), potentially resulting in inadequate care. Improvement in psychiatric treatment within nursing homes could help address this disparity in nursing home quality. Policies offering financial incentives that reward higher-quality care for persons with serious mental illness, similar to current COVID-19–related incentive payments, may help improve quality of care for working-age adults with serious mental illness (

11).

Nursing home admission may be inappropriate for many working-age residents with serious mental illness (

32). Medicaid-certified nursing homes are required to evaluate potential residents for serious mental illness to ensure that they receive necessary services in the most appropriate setting (

33). Many residents in this study could complete activities of daily living independently or with limited assistance, and few were cognitively impaired, indicating that they had the functional capacity to live in a less restrictive environment and potentially obtain supported employment. Those with serious mental illness living in high-support housing (such as nursing homes) report decreased quality of life, compared with those in supportive housing, which has an increased focus on rehabilitation, personal choice, and improvements in social functioning (

34,

35). Additionally, employment can improve quality of life for persons with serious mental illness (

36). In the United States, about 55% of working-age adults with serious mental illness are employed (

37). In addition to supported employment, recommended standards of institutional care for those with serious mental illness include cognitive-behavioral therapy and family interventions (

38). Given the documented substandard treatment of mental illness in nursing homes (

31) and the focus on older adults with physical and cognitive impairments, it is unlikely that these standards are achieved. Enforcement of required evaluation and increased access to community-based alternatives to nursing homes could provide more appropriate support.

The relationship between health inspection ratings and admission of residents with serious mental illness may be affected by factors such as facility ownership and size. For-profit and larger facilities admit a higher proportion of residents with serious mental illness, and both of these characteristics have been associated with worse quality and poorer resident outcomes (

39–

41). For-profit facilities focus on profit maximization, whereas nonprofit facilities aim to fulfill a stated mission (

42). Nonprofit facilities typically have certain tax exemptions and can reinvest excess revenues in improving quality of care (

42). Because of their focus on earnings, for-profit facilities may prefer to admit residents that seemingly require less monitoring and resources, such as working-age adults with serious mental illness (

43). Certain for-profit nursing homes may have also gained a reputation for treating the psychiatric population after deinstitutionalization (

43).

To our knowledge, this is the first study to focus on nursing home residents ages <65 with serious mental illness and quality of the nursing home. Our analyses were limited to use of the data in the MDS 3.0 and NHC, which lack information regarding important characteristics, such as payer mix of nursing homes, dual eligibility for Medicaid and Medicare, health coverage type, and county-level information. Although we adjusted for state-level fixed effects in our model, more detailed geographical variations, such as market factors and urban-rural differences, may be particularly relevant to working-age adults (

44–

46). Longitudinal data and additional data sources, such as Medicaid claims, may be valuable in expanding our understanding of the quality of care received by these residents. Although we used a mixed-effects model to explore group-level and individual-level characteristics, future research should account for individual and group levels more accurately by utilizing micro-macro strategies of multilevel modeling, such as a latent multilevel model (

20). This study is an important first step in better understanding quality of care for working-age adults with serious mental illness in nursing homes. In particular, the VPC of 0.11 highlights the largely unexplored role of facility-level factors and quality of nursing home care among those with serious mental illness.