Bipolar disorder is characterized by discrete episodes of elated-irritable mood (hypomania) and low mood (depression) that profoundly affect psychosocial functioning (

1). The mental health field has increasingly recognized the substantial public health burden of bipolar disorder onset during childhood (

2). More than 50% of individuals who develop bipolar disorder have had illness onset during childhood or adolescence (

3). Of note, those with early-onset bipolar disorder display greater rates of co-occurring psychiatric (e.g., anxiety and substance use disorders) and medical (e.g., asthma and migraine) conditions (

4–

6), as well as greater risk for suicide, than those who experienced bipolar disorder onset in adulthood.

It is therefore not surprising that compared with youths with other psychiatric disorders, youths with bipolar disorder are among the highest users of behavioral health services. In fact, early-onset bipolar disorder is among the costliest psychiatric disorders (

7–

9). Annual health care service use and expenditures for adolescents with bipolar disorder exceed those for adolescents with all other psychiatric disorders (

10). Most previous studies among youths with bipolar disorder have focused on exorbitant health care costs primarily driven by high use of inpatient psychiatric care, emergency services, and medical admissions for suicidal behavior (

10,

11). High rates of psychotropic polypharmacy (

12,

13) and management of resultant adverse effects on general health (e.g., obesity) further drive costs for this population. These data translate into threefold greater annual behavioral health care costs, and twofold greater annual medical health care costs, to treat an adolescent with bipolar disorder compared with an adolescent with a nonbipolar mood disorder.

Although these previous studies have documented high behavioral health service use and associated costs in this high-risk population, they have three important limitations. First, previous studies have largely relied on administrative claims data to identify youths with bipolar disorder. Given that accurate differential diagnosis of bipolar disorder among youths is complex, both over- and underdiagnosis are common in the absence of evidence-based assessment strategies (

14,

15). Thus, claims data alone have questionable diagnostic reliability (

16). Second, previous studies have not distinguished among bipolar disorder subtypes. Debate surrounding the validity and clinical relevance of bipolar spectrum diagnoses that do not meet full

DSM criteria (

1,

17), that is, bipolar disorder not otherwise specified (NOS) and bipolar disorder other specified, further reduce the reliability of claims data because diagnostic criteria for bipolar spectrum disorders have historically been lacking (

18). Operationalized bipolar disorder NOS criteria were developed for the Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth (COBY) study (

19). Similar comorbidity and severity, as well as high rates of conversion to threshold bipolar disorder (i.e., type I or II) during follow-up, have been reported for youths with bipolar disorder NOS (

20,

21). Although

DSM criteria for bipolar disorder type I include hospitalization for mania, and although some previous studies have reported higher rates of psychiatric hospitalization among youths with bipolar disorder type I compared with NOS (

19), little is known about relative rates of hospitalization, or treatment use more broadly, among bipolar subtypes among youths (

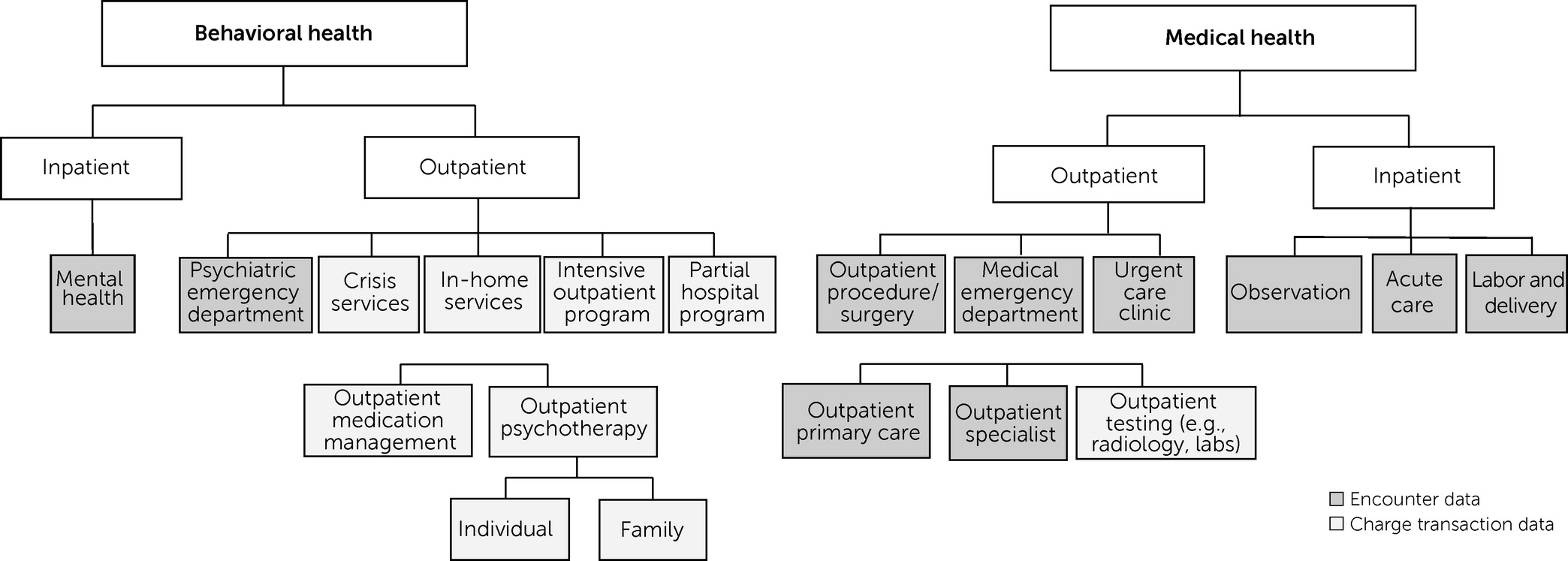

20). Third, previous studies of the service use of youths with bipolar disorder have failed to examine different levels of intensive care (e.g., partial hospitalization and in-home services).

In this analysis, we addressed these weaknesses by linking administrative data to reliable and valid semistructured diagnostic interview data collected after patients entered a randomized psychosocial treatment study. Using electronic health record (EHR) data, we compared differences in behavioral and medical service use between adolescents diagnosed as having threshold bipolar disorder (i.e., type I or II) and bipolar disorder NOS over a 1-year period before study entry. Estimates of both behavioral and medical health service utilization were expected to be high in the sample, with similar rates of behavioral and medical service use across bipolar subtypes.

Discussion

Past-year service use data from this treatment-seeking sample of predominately female (85%) adolescents diagnosed as having bipolar disorder with the use of evidence-based assessment methods showed nearly ubiquitous use of behavioral health services (mainly outpatient psychotherapy) and high rates of general medical service use (mainly outpatient primary care). Nearly half of the adolescents had received a prescription for a psychotropic medication in the preceding year, whereas 59% had been prescribed a nonpsychotropic medication. Service use rates were similar for adolescents with threshold bipolar disorder (type I or II) and with bipolar disorder NOS (derived via operationalized criteria), lending further support for the clinical burden and illness severity associated with bipolar disorder NOS among youths.

In our study sample, 99% of participants had received any behavioral health treatment in the previous year, compared with 80% in naturalistic studies of youths with bipolar disorder (

8) and 62% in community studies (

33). These differences are likely best understood by the fact that the sample in our study sought treatment. Previous findings suggest that youths with bipolar disorder who seek behavioral health treatment have more severe symptoms and functional impairment, as well as greater comorbid conditions and suicidality, than those who do not (

33), observations in keeping with the clinical characteristics of this sample (

8,

33–

36).

Among outpatient behavioral health services, psychotherapy was the most commonly used modality, an observation similar to findings from longitudinal data of the COBY study (

37). Although rates of psychotherapy use in our study were similar to those previously reported in a study using chart review (

13), the rate of medication management visits was lower (43% vs. 99%) in our study than in the previous one. Adolescents in our sample specifically agreed to participate in a psychotherapy study, possibly indicating a preference for psychotherapy over medication. Nearly half (48%) had at least one psychotropic medication listed in their EHR in the previous year, most commonly an antidepressant. Practice guidelines recommend antidepressant use in the presence of a mood-stabilizing medication because of the risk for manic induction (

38). However, the extent to which the patients in our sample used medication according to evidence-based treatment guidelines was not known because of the methods used in our study (

39,

40). These findings highlight the need for further data to investigate adherence to evidence-based treatment guidelines for early-onset bipolar disorder.

Adolescents diagnosed as having bipolar disorder type I or II did not differ from those with bipolar disorder NOS in the overall number or types of psychotropic medications in the previous year. Hirneth et al. (

20) found that youths with bipolar disorder type I used larger amounts of psychotropic medications than youths with bipolar disorder NOS, but these authors used cross-sectional data, and the bipolar disorder NOS criteria differed from those applied herein. It is possible that the similar prescribing patterns observed among bipolar subtypes in our study reflected similar overall clinical presentation and severity of bipolar subtypes, as evidenced by similar age at onset, rates of comorbid conditions, suicidal behavior, and hospitalizations.

Although adolescents with bipolar disorder represent a relatively small proportion of psychiatric patients, previous studies have indicated that they account for a disproportionately large percentage of psychiatric inpatient hospitalizations (

41). In our sample, 19% had at least one psychiatric hospitalization in the previous year, compared with 30%–40% previously reported among privately insured youths with bipolar disorder (diagnosis per claims data) (

7,

10) and nearly 60% in one study (which used chart review) (

13). Additionally, although some studies have reported higher rates of psychiatric hospitalization among youths with bipolar disorder type I compared with bipolar disorder NOS (

18,

20), no differences in psychiatric hospitalization were observed among the different bipolar subtype groups in this sample. Previous studies have reported considerable inpatient hospitalization and expenses specifically attributable to suicide attempt among adolescents with bipolar disorder (

7,

8,

29). Thus, the lack of differences between bipolar subtypes in suicide attempt rates in the sample of this study may explain the comparable rates of hospitalization among patients in these subtype groups. Thus, suicide risk (possibly more so than mania) among youths with bipolar disorders may have substantial implications for health system approaches, clinical management, and cost in the management of early-onset bipolar spectrum disorder.

Our findings may also reflect increased efforts to use less restrictive treatment settings for the management of suicide risk in recent years (

42). Indeed, nearly half of the sample used other intensive behavioral health services, including crisis services, partial hospitalization services, and intensive outpatient programs; yet, most previous studies did not report on such services. These interim levels of care may function to prevent inpatient hospitalization for this population (

43). Similarly, intensive evidence-based psychotherapy approaches for adults with bipolar disorder are associated with decreased risk for psychiatric hospitalization (

40). A forthcoming randomized trial of one such intervention (dialectical behavior therapy) (

44) for adolescents with bipolar disorder will examine this possibility.

Of the sample in this study, 78% used some type of general medical health service in the previous year. Outpatient primary care visits were most common (67%). Dusetzina et al. (

7) also found high rates of nonbehavioral health outpatient visits among youths with bipolar disorder. Medical nonbehavioral ED visits (39%) and medical outpatient specialist visits (30%) were also common, highlighting significant co-occurring medical conditions. As such, adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders should be carefully assessed for general medical and psychiatric risks (

4). Furthermore, as advocated by Aarons et al. (

5), interdisciplinary communication is critical. The evidence-based coordinated specialty care model implemented in first-episode psychosis (

45) promotes shared decision making between the patient and a team of specialists and may be a promising delivery model for the management of early-onset bipolar disorder.

Our findings should be considered within the context of some study limitations. Primarily, the sample included adolescents who consented to participate in a psychosocial treatment study. As such, their service use may not reflect uses in community samples. Given data indicating no sex differences in rates of early-onset bipolar spectrum disorder (

46), the overrepresentation of females in the sample of our study may be explained by findings that females are more likely to seek psychotherapy (

47). Yet, use of this sample enabled confirmation of bipolar spectrum disorder diagnosis from a semistructured interview, a significant strength compared with many previous studies that relied only on EHR diagnoses.

Other limitations included a primarily White sample. Given evidence of health care disparities in bipolar disorder (

48), further examination in more diverse samples is warranted. Because this study relied on data from within one large system of care in western Pennsylvania, it is possible that adolescents used additional services outside of this system that were not captured. Yet, we note that compared with self-reported service use data, such objective data are more reliable (

49) and may provide a higher degree of granularity. We also did not have information on services covered under adolescents’ insurance plans, which may have influenced service use. However, under the Affordable Care Act, public and private insurers are required to cover mental health services at parity with general medical benefits (

50). Future studies may further expand on this work by examining lifetime service use (compared with previous year) to enhance the understanding of patterns of service use over time.