The implementation of evidence-based practices (EBPs) is a central component of the ongoing shift from volume to value in behavioral health care, which entails moving from a focus solely on the quantity of care provided to a focus on the quality of care provided (

1). Achieving successful uptake of EBPs requires the participation of various stakeholders, including clinicians, supervisors, agency executives, and payers, for whom the costs and benefits of delivering EBPs likely differ (

2). These differences may influence stakeholders’ preferences for implementation strategies, which can be defined as the active approaches used to increase the adoption and sustainment of interventions (

3).

Previous studies have noted divergent preferences for implementation strategies across different stakeholders in behavioral health care, and these differences could represent barriers to effectively delivering EBPs (

2,

4). Therefore, a better understanding of stakeholders’ inclinations toward implementation strategies, including financial incentives and performance feedback, could unveil new opportunities to enhance the quality of behavioral health care (

5,

6).

In this study, we leveraged a choice experiment survey on different strategies for implementing EBPs; the survey was administered to multiple stakeholder groups in a large publicly funded behavioral health care system. The survey elicited preferences for 14 implementation strategies, derived from an innovation tournament (

7) and the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) taxonomy (

8), that aim to support the delivery of EBPs, enabling us to measure preferences within and across stakeholder groups.

Methods

We used a best-worst scaling choice experiment in a survey conducted in March and April 2019 to measure the preferences for implementation strategies for EBP delivery among different stakeholders associated with Community Behavioral Health, the sole behavioral health, managed-care organization serving Medicaid beneficiaries in Philadelphia (

9). Initially, we sent survey invitations via e-mail to leaders (N=210) and clinicians (N=527) of behavioral health organizations. We also e-mailed the invitation to four local electronic mailing lists and asked organization leaders to forward the e-mail. The survey link was opened 654 times; 357 respondents (N=240 clinicians, N=74 direct supervisors, N=29 agency executives, and N=14 payers) completed the survey, and their responses were included in this study.

The survey included 14 implementation strategies for delivering EBPs; the strategies were developed through a crowdsourced process that engaged local clinicians in an innovation tournament, followed by refinement and operationalization of the strategies in partnership with an expert panel of implementation and behavioral scientists (

10). The implementation strategies were the following: an EBP performance leaderboard that recognizes clinicians in the agency who met a prespecified benchmark, posted where only agency staff can view it; an EBP performance benchmark e-mail available to a clinician and their supervisor; peer-led consultations comprising monthly telephone calls led by a local clinician with experience implementing EBPs; expert-led consultation including an expert EBP trainer on monthly telephone calls; on-call consultation consisting of a network of expert EBP trainers available for same-day, 15-minute consultations via telephone or Web chat; community mentorship consisting of a one-on-one program in which clinicians are matched with another local clinician treating a similar population; a confidential online forum available only to registered clinicians who use an EBP; a Web-based resource center that includes video examples of how to implement an EBP, session checklists, and worksheets; electronic screening instruments that could be added to an electronic health record to be completed by clients in a waiting room; a mobile app and texting service providing clients with reminders to attend sessions and complete homework assignments; a more relaxing waiting room that better prepares clients to enter the session; a one-time bonus for verified completion of a certification process, consisting of four training sessions, a multiple-choice examination, and the submission of a tape demonstrating EBP use; additional compensation for preparing to use an EBP in a session (e.g., reviewing protocol); and additional compensation for EBP delivery.

Respondents viewed 11 randomly generated quartets of the 14 implementation strategies; within each quartet, they selected the strategy they considered to be “most useful” and “least useful” for helping clinicians to deliver EBPs. Randomization of implementation strategies was balanced with regard to the number of times shown, pairing with other implementation strategies, and ordering within the presentation sequence.

To assess preferences for different implementation strategies among survey respondents, we calculated preference weights for each implementation strategy by using empirical Bayes estimation (

11). Higher preference weights indicated that respondents felt the implementation strategy was “more useful.” The range of empirical Bayes weights can vary widely by the extent of favorability and unfavorability, but the same survey will generate empirical Bayes weights that are directly comparable on a ratio scale. For example, a preference weight of 10 is twice as favorable as a preference weight of 5 and five times as favorable as a preference weight of 2 (in our survey, the highest favorability was defined as the “most useful”).

To ease interpretation, we grouped the 14 implementation strategies into six categories developed by the ERIC project: performance feedback, client supports, clinical social supports, clinical consultation, clinical support tools, and financial incentives (which ERIC refers to as “pay for performance”) (

8). We averaged preference weights for individual implementation strategies within categories and then calculated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to allow for pairwise comparisons among the four stakeholder groups. Differences were deemed statistically significant if the 95% CIs did not overlap. In a supplemental table in the

online supplement, we tested for differences in preference weights for individual implementation strategies across the four stakeholder groups (clinicians, supervisors, agency executives, and payers) by using both CIs and analysis of variance.

Additional details on the innovation tournament, best-worst scaling choice experiment, and empirical Bayes estimation are available elsewhere (

2,

7,

12). This study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

Results

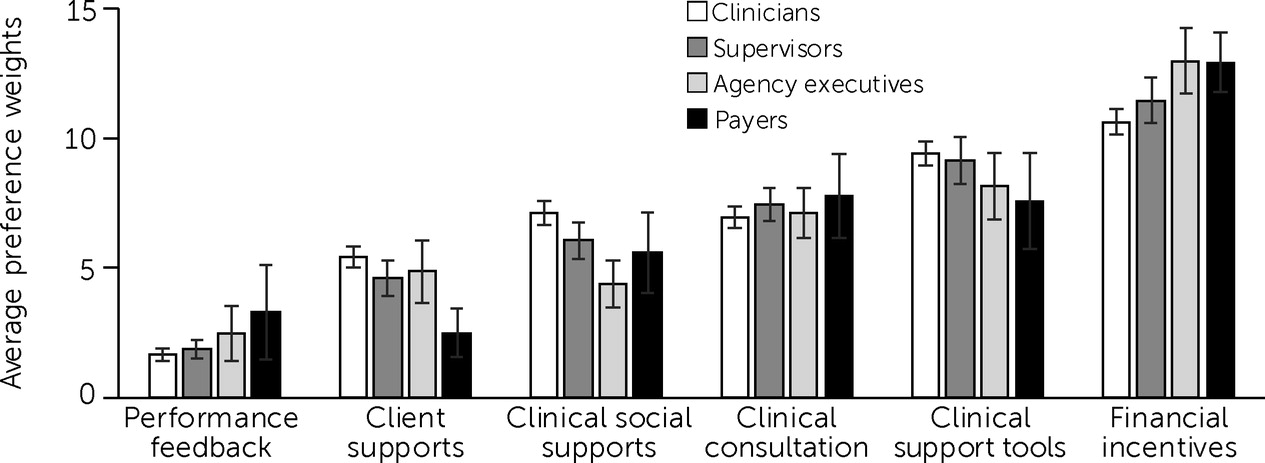

The four stakeholder groups agreed that the financial incentives category of implementation strategies was most useful for EBP implementation (

Figure 1). The average preference weights for financial incentives were 10.6 for clinicians (95% CI=10.1–11.1), 11.5 for supervisors (95% CI=10.6–12.4), 13.0 for agency executives (95% CI=11.7–14.3), and 12.9 for payers (95% CI=11.8–14.1). The stakeholders also agreed that performance feedback strategies were the least useful; mean preference weights for the performance feedback strategies were 1.7 for clinicians (95% CI=1.4–1.9), 1.9 for supervisors (95% CI=1.5–2.3), 2.5 for agency executives (95% CI=1.4–3.5), and 3.3 for payers (95% CI=1.5–5.1).

There were notable points of divergence in preferences for individual implementation strategies across stakeholder groups (see Table S1 in the

online supplement). For example, we observed statistically significant differences regarding the preferred structure of financial incentives. Preference weights for compensation for EBP delivery were significantly higher for payers (preference weight=17.5, 95% CI=15.3–19.8) compared with clinicians (preference weight=11.6, 95% CI=10.9–12.3). In contrast, clinicians ranked the usefulness of compensation for EBP preparation time (preference weight=11.7, 95% CI=11.0–12.4) more highly than did payers (preference weight=10.3, 95% CI=6.8–13.9), although the difference between these two groups was not statistically significant.

Discussion

In this study, we used a choice experiment survey to elicit and compare preferences for EBP implementation strategies among clinicians, supervisors, agency executives, and payers in a large publicly funded behavioral health care system. Of note, innovation tournaments and the best-worst scaling choice experiment used to elicit preferences are relatively low-cost approaches and increase stakeholder engagement (

12). Such approaches confer opportunities to rank the order of and customize implementation strategies, and systematic reviews have concluded that participatory design based on crowdsourcing is an effective way to identify innovative solutions to complex issues (

12,

13).

Our results indicate that stakeholder groups agreed on the most useful category of implementation strategies (financial incentives) as well as on the least useful category (performance feedback). Given the growing popularity and acceptability of financial incentives in health care (

5,

14), a notable point of divergence involved the structure of financial incentive implementation strategies. Clinicians preferred compensation for EBP preparation time and delivery similarly, but payers significantly preferred compensation for EBP delivery over compensation for EBP preparation time.

To date, the shift from volume to value of care has yielded mixed results in behavioral health (

5). Financial incentives traditionally reward the delivery of services, overlooking the time and resources clinicians need to prepare for EBP delivery in community settings—particularly in publicly funded behavioral health care (

15). Our findings suggest that one way to support clinicians in EBP implementation is to consider restructuring financial incentives to align with clinicians’ preference for reimbursement for EBP preparation time or to explore the possibility of using procedural codes that reimburse EBP preparation time.

Determining whether compensation for EBP preparation time can meaningfully increase EBP delivery and identifying the best ways to operationalize this and other implementation strategies were outside the scope of this study. Qualitative interviews of stakeholder focus groups could be useful for further refinement of these ideas. Our results were also limited in generalizability because our survey targeted stakeholder groups associated with Philadelphia Medicaid. Finally, we note a lack of established cutoffs to determine whether levels or differences in preference weights among stakeholders are clinically meaningful.