Approximately 10%−20% of individuals with schizophrenia and other serious mental illnesses are competitively employed (

1), which contributes to their improved physical and mental health, quality of life, social capital, and reduced poverty (

2,

3). The individual placement and support (IPS) model of supported employment focuses on rapid job placement through job development with ongoing supports (

4,

5) and is more effective than other supported employment programs at improving competitive work outcomes (

6). Still, approximately 45% of IPS clients do not obtain competitive employment (

7).

Job interviews are an established factor contributing to successful job attainment in both the general population (

8–

11) and among individuals with psychiatric or other disabilities (

12–

15). Job interviewing is anxiety provoking for most people (

16) and more so for individuals with serious mental illness, who are prone to anxiety and often have impairments in their interpersonal skills (

17,

18). Given that interviewing skills predict employment among individuals with serious mental illness (

12,

13,

19,

20), improving such skills could be an important treatment target to enhance IPS outcomes. However, research focused on job interview skills training has not yet occurred within IPS. Although training in interviewing skills is not a core component of IPS (

21,

22), it is recommended that employment specialists engage clients in practice interviews when needed (

21–

24). However, it is not known how frequently employment specialists engage their clients in practice interviews for jobs or whether job interview skills are improved by such practice, nor are the benefits of improving job interviewing skills in IPS known. Thus, tools to facilitate the training of interviewing skills among persons receiving IPS have the potential to improve work outcomes.

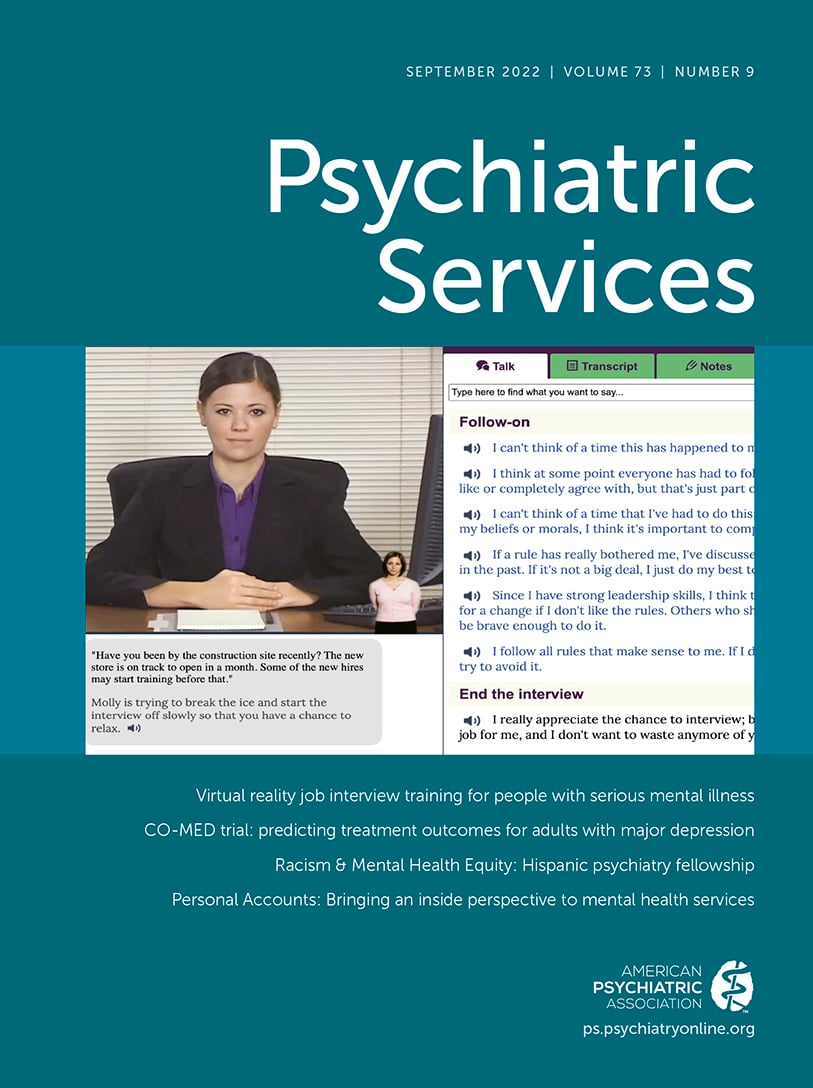

To address the need for improved tools to facilitate job interviewing training, a computerized job interview simulator, called Virtual Reality Job Interview Training (VR-JIT; www.simmersion.com), was developed to provide individuals with serious mental illness an opportunity to practice and hone their interview skills while receiving automated feedback. Prior evaluation of VR-JIT in a series of laboratory-based randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for job-seeking individuals with serious mental illness found that VR-JIT improved participants’ interview skills and self-confidence, led to more competitive job offers, and was associated with a shorter time to employment (

25–

31). Although approximately 30% of the participants in these efficacy studies were engaged in vocational rehabilitation, none of these studies were embedded within IPS (

25–

31).

The RCT reported here evaluated the effectiveness of VR-JIT when delivered within a high-fidelity IPS supported employment program. The primary hypotheses were that the provision of VR-JIT in addition to IPS would result in better employment outcomes, compared with IPS alone. Secondary hypotheses were that participants receiving VR-JIT would have greater improvements in interview skills, interview self-confidence, and interview anxiety, compared with those receiving IPS as usual.

Discussion

Job interview skills are a critical contributor to employment (

47). IPS supported employment is the most effective psychiatric rehabilitation approach to promote competitive work among individuals with serious mental illness (

7). However, the impact of training IPS participants in interviewing skills has not been evaluated. VR-JIT was developed as an efficient approach to interview training by providing clients with the opportunity to practice their interviewing skills and obtain real-time feedback through a computer-based virtual platform. Our primary results were not definitive, because the unadjusted results were nonsignificant and statistically underpowered because of COVID-19 pandemic–related recruitment shortfall. However, adjusting the model for covariates that were theoretically and empirically associated with employment indicated that participants randomly assigned to IPS+VR-JIT were significantly more likely than those in the IPS-as-usual group to obtain employment within the 9-month study period. A similar pattern was noted for the Cox proportional hazards model, in which the unadjusted analysis yielded a nonsignificant effect, whereas the adjusted results indicated a trend that IPS+VR-JIT participants had a shorter time to employment, compared with IPS-as-usual participants. Overall, these results are consistent with prior efficacy trials of VR-JIT among individuals with serious mental illness who were not engaged in vocational rehabilitation (

26,

27,

29).

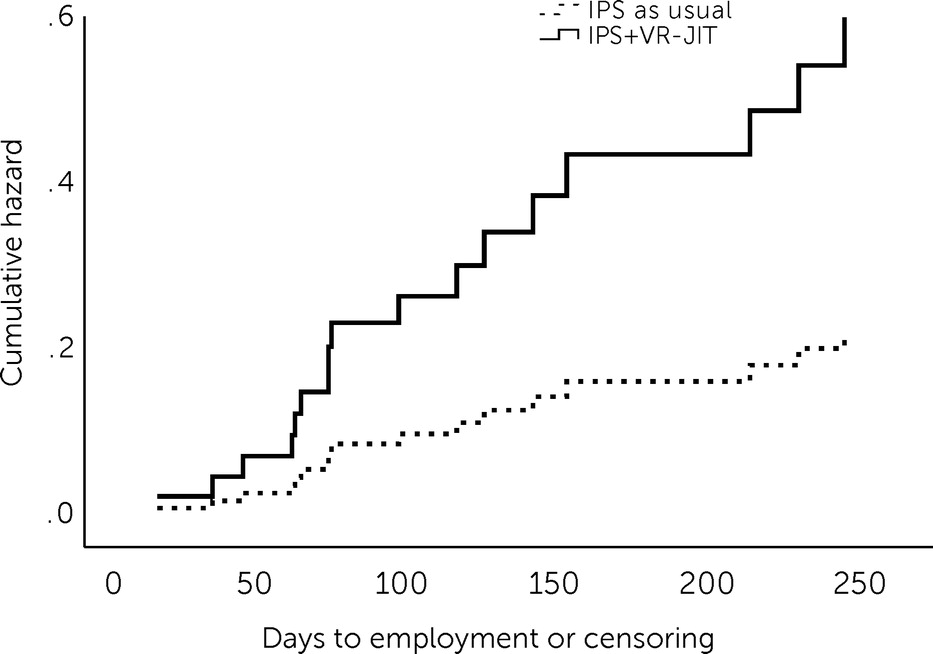

We know that approximately 45% of IPS clients are unable to obtain employment (i.e., IPS nonresponders) (

7) and that additional supports or tools may improve employment outcomes for this group. Our post hoc analyses suggested that IPS nonresponders who received VR-JIT had significantly greater odds of employment and reduced time to employment (

Figure 1), compared with nonresponders in the IPS-as-usual group. The results demonstrating that IPS nonresponders seem to benefit from VR-JIT are consistent with other lines of research also suggesting that individuals who do not initially benefit from IPS may be able to secure employment with adjunct services integrated within IPS (e.g., cognitive remediation) (

37). Overall, our change in eligibility criteria enabled us to detect that VR-JIT may enhance employment outcomes among IPS nonresponders while concurrently providing insight that not all IPS clients may benefit from additional interview training. Notably, the effects of VR-JIT on IPS nonresponders was not hypothesized and requires replication.

We also found that VR-JIT facilitated improved interview skills, interview self-confidence, and interview anxiety for participants, which is consistent with prior trials evaluating VR-JIT among adults with serious mental illness (

25–

31) and an adapted VR-JIT among autistic transition-age youths (

50). These findings have important implications, because self-confidence is known to improve interview performance (

68), and high levels of anxiety can disrupt interview performance (

16,

69,

70). Although IPS+VR-JIT participants improved their interviewing skills, no improvement was shown for general social competence, which is consistent with research and clinical recommendations that social skills training may improve specific targeted areas of social functioning but has limited generalizability to other areas (

71).

Implications for Practice

Given the focus on rapid job search in IPS, employment specialists may or may not work with clients on interview skills preceding real-world job interviews. Further, there is limited information from prior studies about how many IPS clients practice job interview role plays. Notably, we observed that approximately 47% (N=17) of participants in the IPS-as-usual group completed 1.8±1.2 practice job interviews with their employment specialists. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report on the frequency of mock interviews occurring within IPS. That said, employment specialists are not currently trained in established social skills methods for teaching interview skills. With VR-JIT’s use of behavioral learning principles, including scaffolding and performance feedback, the intervention’s pedagogy is consistent with evidence-based social skills training approaches (

71).

As noted in this study, engagement with VR-JIT combined with high-fidelity IPS significantly reduced time to obtaining competitive employment for IPS nonresponders. Further, IPS employment specialists spent 38.8±41.9 minutes discussing virtual interviewing progress with IPS+VR-JIT participants, indicating that employment specialists could naturally integrate VR-JIT into the IPS service structure. Thus, the enhancement of IPS with VR-JIT addresses an area of need—namely, poor interview skills, which could be contributing to a diminished response to IPS for some clients. Improved interview skills could serve to bolster work outcomes, not only in IPS but also in a variety of highly utilized vocational rehabilitation services in the United States and internationally.

Because a large proportion of participants engaged in IPS as usual completed job interview role plays with their employment specialists, providing employment specialists with evidence-based tools to facilitate and standardize this training could bolster their practices. Thus, VR-JIT could potentially offer employment specialists a tool to assess and guide interview skills development for IPS nonresponders without affecting IPS fidelity, serving to enhance the impact of IPS in much the same way as motivational interviewing and cognitive remediation strategies. For example, employment specialists could train clients to use VR-JIT independently and then process transcripts and summary performance assessments with them. Alternatively, employment specialists could review clients’ VR-JIT performance assessments and transcripts prior to sessions with clients and then use the sessions to reinforce their clients’ interviewing strengths and focus in greater depth on interview skills that need improvement.

Although the data are preliminary and future studies are needed, this more naturalistic integration of VR-JIT with employment specialist support generated the best employment rates among all study participants: mock interviewing with the employment specialist plus VR-JIT, 56% (N=9); mock interviewing with the employment specialist alone, 40% (N=15); VR-JIT alone, 40% (N=43); and no mock interviewing with the employment specialist or VR-JIT, 24% (N=17). Finally, Internet-based programs, such as VR-JIT, provide IPS teams and individuals with serious mental illness flexible access and use of tools that can facilitate practice at their convenience and pace and could facilitate engagement in IPS for individuals with serious mental illness who face unexpected barriers to face-to-face meetings (e.g., inclement weather and transportation barriers), although future research is needed to examine potential barriers more carefully.

Limitations

The findings must be considered within the study limitations. First, the observed employment rates in both groups were lower than anticipated when considering other studies evaluating high-fidelity IPS (

6). These lower-than-anticipated rates can potentially be explained by two factors. The first was that 51% (N=46) of the main sample included IPS nonresponders (i.e., individuals who did not benefit from IPS). The second was that 49% of the main sample were recent IPS enrollees, and one could estimate that 45% of these participants would become IPS nonresponders during the course of the study (based on historical IPS employment rates) (

7). Second, overall recruitment challenges and the COVID-19 pandemic contributed to a smaller sample and significantly lower analytical power than anticipated. Notably, 24% of our sample (N=22) had at least 1 month of follow-up during the COVID-19–imposed quarantine period (March 2020 through October 2020). That said, 50% (N=11) of these participants obtained employment, which was consistent with the 45% employment rate at Thresholds during the quarantine. Thus, the pandemic appears to have had minimal impact on job attainment in this study.

A third limitation is that employment specialists were asked to refrain from mock interview training with IPS+VR-JIT participants and were not masked to study condition. This design may have facilitated bias in how the employment specialists treated participants in both groups. That said, we did not see a difference between groups with respect to the extent that employment specialists discussed job interview skills with the participants. This lack of a difference could reflect minimal bias or a potential increase in job interview skill discussion in the IPS-as-usual group. Fourth, findings regarding interview confidence and anxiety were limited to self-report. Finally, VR-JIT was primarily implemented by researchers, which may limit our understanding of its effectiveness when implemented by IPS staff. However, VR-JIT was delivered by using strategies and procedures recommended by IPS program administrators and in settings where participants typically met with their employment specialists to mirror real-world delivery.

Future Directions

Additional research is needed to help understand why VR-JIT may be effective in helping IPS nonresponders. For instance, research is needed to evaluate differential effectiveness of VR-JIT among IPS nonresponders and its mechanisms of enhanced interview skills and employment. Also, although VR-JIT was primarily implemented in the community by researchers, our hybrid type I design included an initial process evaluation of VR-JIT implementation feasibility, acceptability, and usability and potential barriers to future implementation—and that report is forthcoming. Meanwhile, a future multilevel implementation evaluation of VR-JIT is needed to assess how VR-JIT is delivered by IPS teams to IPS nonresponders while maintaining the core functions of high-fidelity IPS and how VR-JIT fits into the IPS workflow and progress note for services billing to further enhance and sustain implementation. Finally, agencies and interested implementers would benefit from understanding the cost-effectiveness of VR-JIT.