Care coordination must improve if the triple aim of improving the health care experience, improving the population’s health, and decreasing the cost of health care is to be achieved. The Affordable Care Act included a provision establishing Medicaid health homes for individuals with or at risk of developing multiple chronic conditions or with serious mental illness (

1). The goal of this program was to reduce the costs of unnecessary inpatient utilization by supporting care transitions, removing individuals’ social and economic barriers to care, and engaging people in the behavioral and general medical care they need to stay well. Studies on other health home models have been limited and have not evaluated the models’ effectiveness in reducing preventable hospitalizations or their impacts on other salient health outcomes (

2–

5).

New York State launched its health home program in 2012 as part of a state plan amendment to its Medicaid program (

6). New York’s health home model expanded four existing Medicaid programs that address specific health issues—a targeted case management program for serious mental illness, managed addiction treatment services for substance use disorders, specialized HIV care management, and a limited chronic illness demonstration project to help people with multiple chronic conditions. Although almost 1 million people were eligible to participate when New York launched its health home program, the state initially prioritized the enrollment of 500,000 adults on the basis of need, with preference weighted toward individuals with mental health or substance use conditions. The state began implementing a separate health home serving children in 2016. By early 2020, over 180,000 individuals were enrolled in health homes in New York (

7).

In the New York model, health home enrollment is voluntary. Eligible individuals—identified through claims by the state, a Medicaid managed care organization, or a provider or directly by a care management agency—are contacted by the care management agency and given the option to enroll (

6). Once a member is enrolled, health homes receive per-member-per-month payments from the state, which are adjusted on the basis of the member’s health and social needs, to conduct the core health home activities for each member: “comprehensive care management; care coordination and health promotion; comprehensive transitional care from inpatient to other settings; individual and family support; referral to community and social support services; and the use of health information technology to link services as feasible” (

2).

Health home implementation coincided with the phased inclusion of almost all Medicaid beneficiaries in managed care and the creation of health and recovery plans (HARPs), which are Medicaid special needs plans specifically for individuals with serious mental illness and repeated hospitalizations. HARPs offer health home enrollment as a standard benefit. Members are assessed to determine the appropriateness of other home- and community-based rehabilitation services.

Our study consisted of a pre-post analysis of inpatient utilization—the main focus of the health home initiative—for health home enrollees receiving mental health treatment. This research arose from a project funded by a grant from the Transforming Clinical Practice Initiative of the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation. The project engaged over 3,500 behavioral health specialty care providers in the New York State practice transformation network to enhance the care coordination capacity of community behavioral health centers and prepare them for value-based payment.

Methods

Claims data were accessed through the Medicaid Data Warehouse under a data use agreement with New York State. Our sample comprised individuals who received mental health services from a provider in the state’s practice transformation network between January 1, 2015, and December 31, 2016; were enrolled in a health home during that time; were enrolled in Medicaid for the 12 months before and after their health home enrollment; and remained enrolled in their health home over those 12 months. We extracted those individuals’ claims data after June 2019 for the 1 year before (preenrollment year 1) and 2 years after (postenrollment year 1 and postenrollment year 2) the individuals enrolled in a health home to allow for more than 6 months of lag for all claims (to obtain the most complete claims data). We excluded all individuals who were not eligible for Medicaid during preenrollment year 1 and postenrollment year 1, and we excluded individuals from the postenrollment year 2 analysis who were not eligible for Medicaid during that time. Because the study used retrospective, deidentified data, institutional review board approval was not required.

For the individuals included, we extracted demographic and clinical characteristics, including age, gender, type of Medicaid coverage (i.e., either regular coverage based on Temporary Assistance for Needy Families eligibility or HARP), Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score (a score—on a scale from 0 to 24, with higher scores indicating more severe comorbid conditions—that is based on current health conditions and predicts 1-year mortality) (

8,

9), individual general medical comorbid conditions, and psychiatric diagnosis (bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, other psychotic disorders, substance use disorder).

We also extracted utilization data for each year, categorized them on the basis of utilization setting (inpatient, emergency department, or outpatient), and further stratified them by primary diagnosis (mental health, substance use, or general medical health). Medications were categorized on the basis of whether they were used for behavioral health or nonbehavioral health. Medications were categorized as being used for behavioral health if they were on the list of medications included in quality measures related to depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and medication-assisted substance use treatment listed in the National Committee for Quality Assurance Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set. Methadone was excluded because it is billed through in-person visits and is not a prescribed medication filled by an external pharmacy. All other medications were categorized as being used for nonbehavioral health.

Patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics were summarized for preenrollment year 1, postenrollment year 1, and postenrollment year 2. We computed the prevalence of health conditions used to calculate the CCI score and listed those that increased more than 20% over the 3-year study period. Utilization was summarized and standardized as the number of units of utilization (inpatient discharges, outpatient or emergency department visits, prescriptions filled) per 1,000 patients. We compared utilization during postenrollment years 1 and 2 separately with utilization during preenrollment year 1 to determine the change in utilization over time.

Results

We used data from 10,193 individuals who met inclusion criteria (see the online supplement to this column). Of these, 7,604 individuals retained 12 months of Medicaid eligibility and health home enrollment in postenrollment year 2. In preenrollment year 1, the average age of individuals in the cohort was 45 years, 59.0% (N=6,014) were female, and 57.9% (N=5,902) were enrolled in HARP. The average CCI score was 3.01, a serious mental illness (i.e., bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or another psychotic disorder) was reported for 51.0% (N=5,198) of patients, and 33.0% (N=3,364) had substance use disorders. Over the 3-year time frame, the rate of these serious mental illnesses, based on the preponderance of diagnoses attached to claims, decreased to 36.0% (N=2,737 of 7,604), and the rate of substance use disorder diagnoses decreased to 27.0% (N=2,053 of 7,604).

The mean CCI score increased to 3.30 in postenrollment year 1 but then decreased to 3.27 in postenrollment year 2. Of the 17 conditions used to calculate the CCI score, the prevalence of five increased by more than 20% over the 2-year time frame (preenrollment year 1 to postenrollment year 1): metastatic solid tumors increased by 27.7% (N=65 to N=83), renal diseases increased by 97.3% (N=300 to N=592), cerebrovascular diseases increased by 22.4% (N=958 to N=1,173), dementia increased by 38.9% (N=90 to N=125), and diabetes with chronic complications increased by 31.2% (N=1,059 to N=1,389).

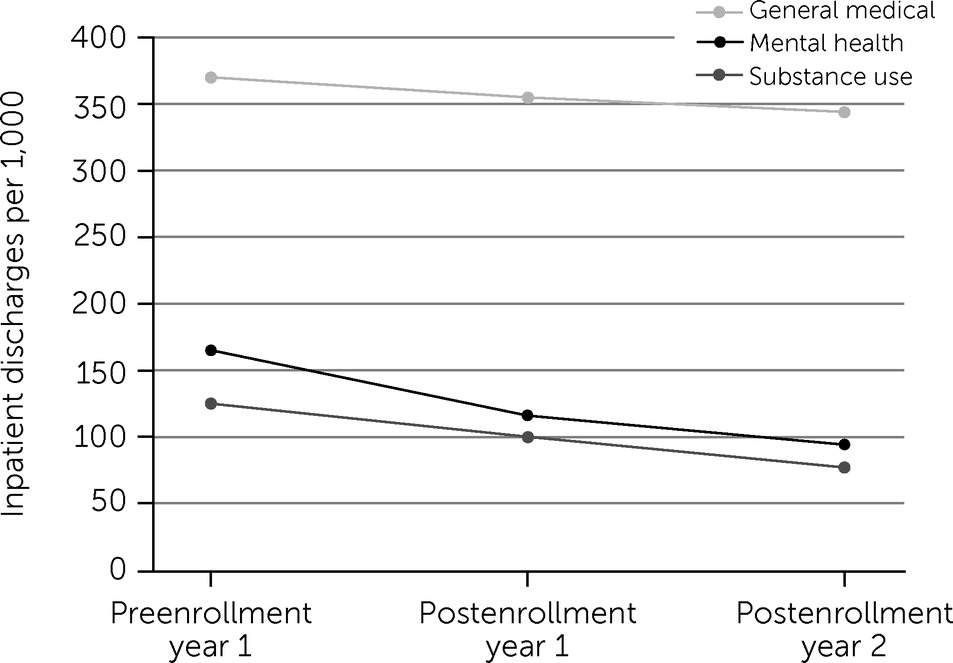

As

Figure 1 indicates, inpatient utilization of all kinds decreased after individuals enrolled in a health home, whereas mental health outpatient utilization increased and substance use outpatient utilization decreased (

online supplement). In postenrollment year 1, inpatient mental health discharges per 1,000 patients declined by 29.7% (N=165 to N=116), substance use discharges declined by 20.0% (N=125 to N=100), and general medical discharges declined by 4.1% (N=370 to N=355). In postenrollment year 2, inpatient mental health discharges declined by 43.0% (N=165 to N=94), substance use discharges declined by 38.4% (N=125 to N=77), and general medical discharges declined by 7.0% (N=370 to N=344) compared with preenrollment year 1. From preenrollment year 1 to postenrollment year 2, outpatient mental health visits per 1,000 patients increased by 28.9% (N=8,859 to N=11,421), substance use visits decreased by 22.0% (N=24,662 to N=19,245), and general medical visits decreased by 3.6% (N=19,380 to N=18,676). Compared with preenrollment year 1, behavioral health medication utilization (

online supplement) increased by 10.6% (N=11,566 to N=12,790) in postenrollment year 1 and by 16.3% (N=11,566 to N=13,453) in postenrollment year 2, and nonbehavioral health medication utilization increased by 7.7% (N=54,288 to N=58,479) in postenrollment year 1 and by 17.6% (N=54,288 to N=63,854) in postenrollment year 2. Emergency department utilization (

online supplement) was minimally affected over postenrollment years 1 and 2.

Discussion

After individuals receiving mental health treatment enrolled in a health home, they experienced dramatic decreases in rates of mental health hospitalization (30% in the first year, 43% over 2 years) and substance use hospitalization (20% in the first year, 38% over 2 years). Although the pre-post design of our analysis precludes a causal interpretation, these findings suggest that health home enrollment may facilitate engagement in behavioral health care. This hypothesis is supported by the 11% increase in behavioral health medication utilization in the first year after enrollment and the 29% increase in mental health outpatient visits over 2 years, although the reasons for the decrease in substance use outpatient utilization are less clear (and may reflect that care coordination and management led to reduced substance use or that substance use was addressed by mental health providers). The reduction in the rate of inpatient treatment for bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and other psychotic disorders, especially during postenrollment year 2, could be a result of individuals with these diagnoses losing coverage more frequently or of their mental health improving such that less severe presentations, such as depression and anxiety, became the focus during treatment encounters.

Individuals receiving mental health treatment also had slight decreases in the rate of general medical hospitalization after enrolling in Medicaid health homes. Although the 7% decrease in general medical hospitalizations by postenrollment year 2 was not as pronounced as the decreases in mental health and substance use inpatient utilization, it may be equally meaningful, given the increasing burden of general medical illness over this period. The approximate 0.30-point increase in CCI score in postenrollment year 1, driven in part by the precipitous rise in serious conditions such as cancers, renal diseases, and cardiovascular diseases, along with the 18% increase in nonbehavioral health medication utilization over postenrollment years 1 and 2, indicates either that this population was becoming increasingly ill over time or that improved follow-up and adherence to general medical care resulted in improved monitoring and diagnosis of underlying disorders. Absent health home enrollment, this population would likely be at risk for even greater rates of general medical hospitalization in the following 24 months, so any decrease in service utilization may be meaningful.

The reductions in inpatient utilization after health home enrollment suggest that, for individuals receiving mental health treatment, health homes may be an effective intervention. More analysis is needed to determine which chronic general medical conditions health homes are effective in addressing and whether effects, if found, are driven by coordinating general medical care or by effectively addressing comorbid behavioral health conditions.

We used a pre-post design for this study rather than a matched cohort or another method that controls for confounding, which means that the observed association between health home enrollment and reduced hospitalization may not be causal. For example, if an increase in inpatient utilization was only temporary, pre-post evaluation might find evidence of reductions in utilization that were driven primarily by the transience of need rather than by the effectiveness of the intervention (

10). Although our study’s population had a disproportionate number of people with complex chronic health conditions and evidence suggests that high-need individuals on Medicaid and with mental health conditions have greater year-to-year persistence in high rates of utilization compared with other populations (

11–

13), so-called regression to the mean still could have occurred.

Selection artifacts may also have had an effect on our findings. The decline in inpatient utilization during postenrollment year 2 and the reduction in more serious mental health diagnoses might mean that only those who were relatively healthy or adherent to treatment were likely to enroll in a health home and remain engaged with care management. Because individuals were excluded from the analysis if they did not remain enrolled in Medicaid for at least the year before and the year after health home enrollment, those who remained enrolled over this period represent a select and biased population for which a health home may be more effective, and the findings may not generalize to others, such as people who do not maintain coverage for 2–3 years. In addition, state policy changes—such as the creation of HARP products and their associated enhanced benefits that extend beyond typical Medicaid services—were also simultaneously occurring during health home implementation, which may have affected inpatient utilization. Future researchers should use an evaluation design that allows them to interpret the causes of observed effects.

In addition, although these findings suggest that health home care management may be effective for individuals with serious mental illness, the heterogeneous models of care management used (

14) make it difficult to link their observed impact with specific interventions (e.g., care coordination, motivational interviewing, or in-person or telephonic outreach) or to determine whether health home interventions were different from the legacy case management interventions. Standardization is lacking among the 300 New York care management agencies, which have varying credentials and training among their workforces, differing caseloads, no consistent supervision or team structure, and a wide range of tasks to be accomplished. Researchers conducting additional studies should compare the effectiveness of different components of health home implementations.

Conclusions

New York State’s implementation of health homes for individuals receiving mental health treatment from a select group of providers was associated with a decrease in inpatient utilization, with the greatest decreases seen for mental health and substance use hospitalizations. This finding supports the hypothesis that New York’s implementation of health homes would reduce preventable hospitalizations for individuals receiving mental health treatment, which needs to be confirmed with studies designed to allow causal inferences. Future researchers should build on this preliminary evidence and support policy makers interested in better meeting the needs of and reducing unnecessary costs for individuals with mental health conditions.