Depression and alcohol use disorder significantly contribute to the global disease burden. Depression contributes to 8% of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) globally, and >80% of the burden of depression is on low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (

1). Alcohol use leads to 5% of DALYs and 5% of all deaths worldwide (

2). The disease burden attributed to alcohol use is highest in low-income and lower-to-middle-income countries (

3). Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic increased the global mental health disease burden by contributing to a dramatic growth in the prevalence of depressive disorder (

4). The increased demand for mental health care and the already vulnerable health care structures in LMICs could lead to long-term impacts on health care access, most acutely in the lowest resource settings (

5,

6).

If left untreated, depression and alcohol use disorder can lead to general medical health problems as well as economic and social problems (

1,

7,

8). Unhealthy alcohol use—that is, alcohol consumption behavior covering the spectrum from risky use to alcohol dependence (

9)—has been shown to increase the risk for infectious illnesses, such as HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis, and noncommunicable diseases, such as liver disease and cardiovascular diseases (

3). Mental disorders led to an estimated US$2.5 trillion loss worldwide in 2010, and this figure is expected to double by 2030 (

10). Alcohol use alone (i.e., costs for all health care related to alcohol use, as well as law enforcement, social work, and indirect costs) accounted for 1%–3% of gross domestic product costs and more than two-thirds of productivity losses (

11). Depression and unhealthy alcohol use can also substantially impair a person’s functioning at work and relationships with family and friends (

1,

3). Given the detrimental social and economic impacts of depression and alcohol use disorder, these disorders are important public health issues, especially in LMICs. However, LMICs face a lack of screening for and diagnosis and management of these conditions (

12). It is estimated that 76%–85% of persons living in LMICs do not have access to appropriate treatment for mental disorders (

13).

In most LMIC settings, primary health care is the population’s first point of contact with the health care system (

14), because primary care centers are located near people’s homes and communities, and in most countries, primary care is either free or more affordable than secondary or tertiary care (

15). Despite these advantages, mental health care in LMICs is predominantly delivered in long-stay mental hospitals and other specialized settings (

16). Therefore, one method for closing the mental health treatment gap is integration of depression and alcohol use disorder care into primary health care. Over the past 15 years, an increasing number of research studies have been conducted worldwide examining the integration of depression and alcohol use disorder care into primary care settings. These studies have been based on the hypothesis that interventions involving mental health integration into primary health care settings could increase screening for and management of mental disorders in LMICs (

8,

15,

17). An additional potential advantage of integrating depression and alcohol use disorder care into primary care is that this approach can be more affordable and cost-effective (

18).

In a recent systematic review, we summarized the evidence published in 1990–2017 of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of integration of depression and alcohol use disorder care into primary health settings (

19). This previous review revealed preliminary evidence of increased effectiveness in the care of patients with depression or alcohol use disorder and evidence of increased direct costs. The previous review also disclosed evidence that these integrations could be cost-effective on the basis of the acceptability threshold and commonly accepted values for cost-effectiveness. Furthermore, that review identified six models for depression and alcohol use disorder care integration and offered a typology with seven strategic levers that decision makers in LMICs can use to deliver care for depression or alcohol use disorder in primary care. The six depression and alcohol use disorder integration models are general training in mental health care for lay health workers and primary health workers, mental health care interventions delivered by lay health workers, mental health care interventions delivered by primary health workers, consultation-liaison, stepped care, and collaborative care.

Table 1 provides a description of this typology, with case examples.

Given the ongoing demand for appropriate depression and alcohol use disorder care in LMICs and the potential to address this treatment gap by integrating such care into primary care, the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2013 advised that assessment and management of mental disorders be conducted in primary health care settings (

20,

21). For this reason, the research community has responded with new work published since 2017. To synthesize the increasing volume of literature in this field, we focused on the same key questions as in the original review; we conducted a quantitative analysis and added studies published since our previous review. We also applied the typology proposed in the previous review and updated our analyses with the newly added studies. We aimed to perform a quantitative synthesis of evidence on the effectiveness of integrating depression and alcohol use disorder care into primary care in LMICs. Additionally, we performed meta-regression analyses on the different models of integration and country income levels.

This meta-analysis is part of Detection and Integrated Care for Depression and Alcohol Use in Primary Care (DIADA), an implementation research study in Colombia, Peru, and Chile, funded by NIMH. The DIADA project studies a technology-enhanced service delivery model for managing depression and unhealthy alcohol use in primary health care at multiple sites in urban and rural Colombia (

22).

Methods

Protocol and Registration

This study was designed in accordance with PRISMA guidelines (

23). This meta-analysis was registered in PROSPERO (identifier CRD42017057340) as an extension of the previous review.

Phase 1: Search Strategy

The study had four phases that mirrored the methods of the previous systematic review. In the first phase, medical librarians developed the search strategy by using the same search strategy from the previous systematic review (

19) but also including articles published from January 1, 2017, to June 23, 2020. The updated search started in 2017 because the previous systematic search was conducted on April 28, 2017, and many databases allow date restrictions by year only. The following databases were searched for relevant articles: MEDLINE-PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, EMBASE, PsycInfo, and WHO’s Global Index Medicus; all databases were searched on June 23, 2020. The updated search resulted in 4,173 abstracts after duplicates were removed. All records before January 1, 2017, were removed, and the updated search yielded 4,053 abstracts. Search keywords included, but were not limited to, “depression,” “alcohol use disorder,” “integrated care,” and “developing country.” (A full list of search terms for all databases searched is available in the

online supplement to this article.)

Studies eligible for inclusion were required to meet the following criteria: they included patients with any severity of alcohol use disorder or depression or both, of any gender, and ≥18 years old; included one or more populations living in an LIMC as per the World Bank country income classification during the year the study described in the article started (

24); included patients who received mental health services (for depression, alcohol use disorder, or both) in fully or partially integrated primary health services; and reported quantitative outcomes to measure effectiveness of the treatment. All single-case studies, presentations, abstracts, notes, and corrections were excluded. All types of study designs were considered. Abstracts in English, Spanish, French, and Portuguese were included. To be included in the meta-analysis, publications needed to report information on the primary outcome measure and statistical analysis details and to include sufficient quantitative data to allow us to calculate an effect size (if not calculated and reported in the article).

Phases 2 and 3: Abstract and Full-Text Reviews

In phase 2, using the inclusion criteria, three teams of two authors (L.C., S.M.B., W.C.T., D.T.J., M.C.) per team independently screened a third of the abstracts and titles (1,351 references). We excluded articles that were study protocols, did not report outcomes, explicitly mentioned other mental disorders as the primary focus, were set in specialized mental health care or in high-income countries, or included participants <18 years. Articles on whose inclusion researchers could not agree (4%) were sent to an arbiter (S.M.B.) who resolved the discrepancies. A total of 94 articles (2% of the original 4,053 abstracts) were selected for full-text screening of inclusion criteria. In phase 3, two teams of two authors each (L.C., S.M.B., W.C.T., M.C.) reviewed the full texts of the included articles by using the same inclusion and exclusion criteria as in phase 2. In each team, one author was designated the primary reviewer, and another author reviewed and assessed the primary reviewer’s work for discrepancies. Any differences were resolved via consensus, or if consensus was not reached, an arbiter (L.C.) resolved the discrepancies. This full-text review identified 49 articles meeting inclusion criteria, 35 of which met study design criteria and provided sufficient statistical data to be included in the meta-analysis. (A flow chart in the online supplement summarizes the process used to search and screen the literature.)

Phase 4: Data Extraction

In phase 4, two teams of two authors each (L.C., S.M.B., W.C.T., M.C.) completed data extraction from each study with a specifically designed form. During the data extraction, the authors also classified each study by using the typology of models of integration from the previous review (

19). Any discrepancies were resolved via consensus, or if consensus was not reached, an arbiter (L.C.) resolved the discrepancies. A standardized assessment of bias of all the included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) was also completed by using methods described in the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias (

25). This bias assessment included a team of two of the authors (S.P., S.M.B.); one acted as the primary reviewer, and the second evaluated the primary reviewer’s work for discrepancies. All discrepancies were discussed until the two reached a consensus.

Phase 5: Merging of Data Sets

In phase 5, the data sets from the previous review (

19) and the present study were merged. For the qualitative synthesis, 49 new articles were combined with 58 articles from the previous review (N=107 studies). Effect sizes were computed from the statistical information extracted during phase 4. If an article reported insufficient data to calculate effect sizes, it was excluded. Of these 107 articles, only 74 (39 of which were from the previous review) provided the quantitative data required for the meta-analysis.

Statistical Analysis

We aimed to identify a summarized index that was computable and comparable across the different instruments, scales, and statistical procedures employed in the included studies. For each study, we calculated a statistic assumed to be asymptotically normally distributed with mean β and standard deviation

, with n and m being the sample sizes in the control group and the treatment group, respectively. With the information reported in the studies, we computed these parameters for each study in various ways. For instance, if the study provided means and standard deviations for both the comparison and the treatment groups, the standardized difference of means was calculated. Similarly, we computed the standardized difference of proportions if proportions (instead of means) were reported. The resulting summarized index is nondimensional, such that if the null hypothesis is true (implementation had no effect), the index has a mean of zero (β

=0)

. If the study reported both depression and alcohol use outcomes, we computed a parameter for depression results and another for alcohol use disorder results. Once the summarized index was identified, a random-effects model (DerSimonian and Laird methodology) was estimated for each study for alcohol use disorder and depression outcomes separately. The I

2 was generated to measure heterogeneity within and among studies. Meta-regression analysis was then used to analyze consistency of the results. Both effect sizes and 95% CIs are reported. Additionally, the Eggert test and a funnel plot analysis were conducted to evaluate publication bias of the included studies. All analyses were performed with the R package metafor and meta, available in CRAN (

www.r-project.org).

Results

Description of Included Studies

In total, 74 studies from 69 articles from the previous review and this updated study were evaluated in the meta-analysis (for a description of the included studies in the meta-analysis, see the online supplement). The included articles assessed the effectiveness of depression and alcohol use disorder care integration into primary care in LMICs.

Of the 74 studies, 54 included both men and women, 19 only women, and one only men. Twenty studies took place in rural settings only, eight in semiurban settings only, and 16 in urban settings only. Seventeen studies were conducted in both rural and urban settings; one in both semiurban and urban settings; one in both rural and semiurban settings; one in rural, semiurban, and urban settings; and the settings for the remaining 10 were unclear. The rurality of the studies’ settings was evaluated primarily on the basis of the description of the setting in each article. If the description was unclear, a definition from the United Nations Statistical Commission was used to classify the setting (

26). On the basis of the World Bank classification during the year the studies started (

24), nine were conducted in low-income countries, 39 in lower-to-middle-income countries, and 26 in middle-to-upper-income countries. According to the WHO regional grouping classification (

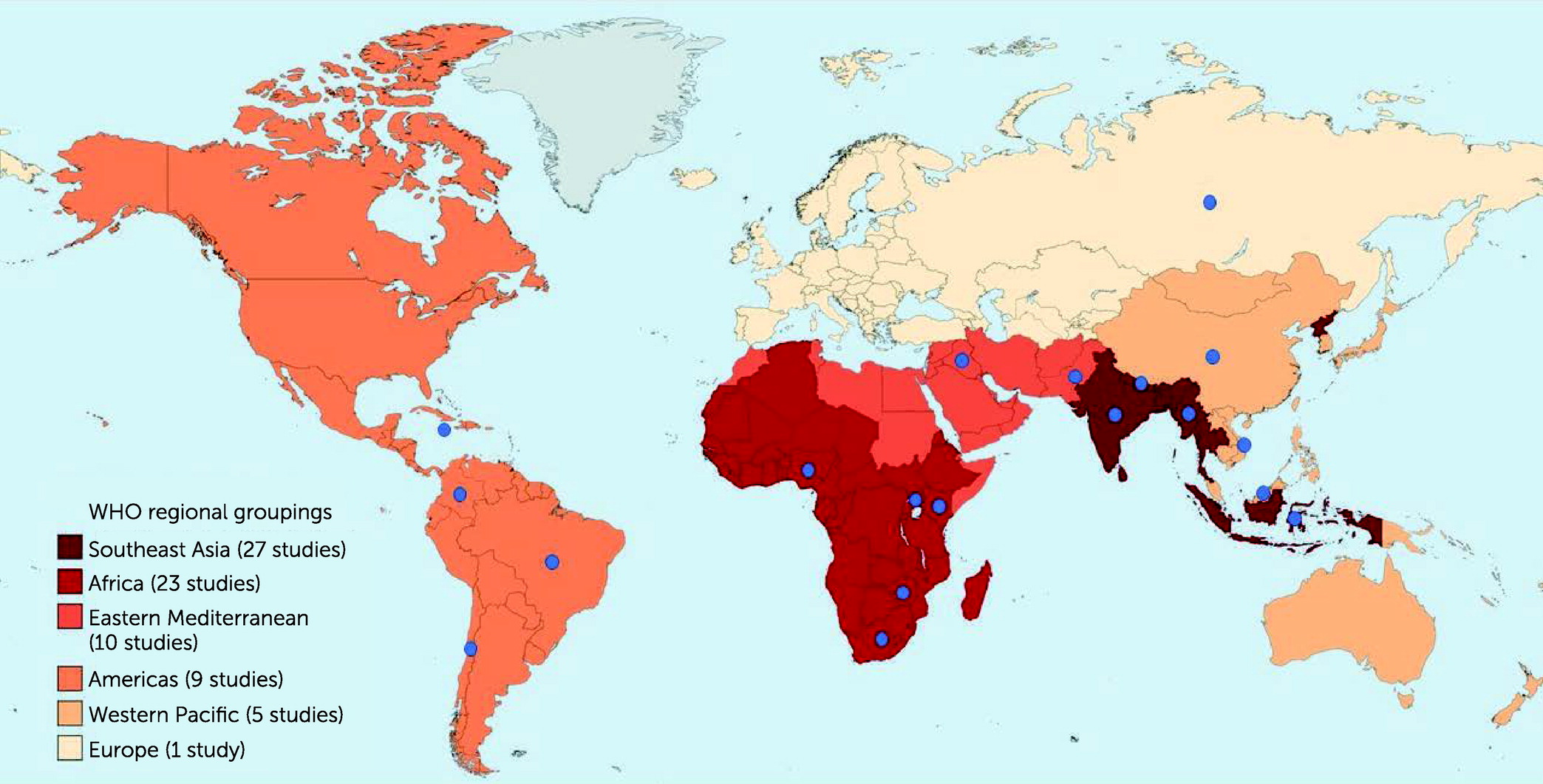

27), 27 studies were conducted in Southeast Asia, 23 in Africa, 10 in the Eastern Mediterranean, nine in the Americas, five in the Western Pacific, and one in Europe. (One study took place in both India and Pakistan, which was categorized into two different regions.)

Figure 1 shows the geographical settings of the included studies by WHO regional groups and individual countries.

Fifty-three of the studies focused on depression only, 14 on alcohol use disorder only, and seven on both depression and alcohol use disorder. Additionally, 70 studies evaluated the effectiveness of the integration models, and four evaluated both effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the integration models. Overall, 63 studies were RCTs, and 11 were quasi-experimental studies.

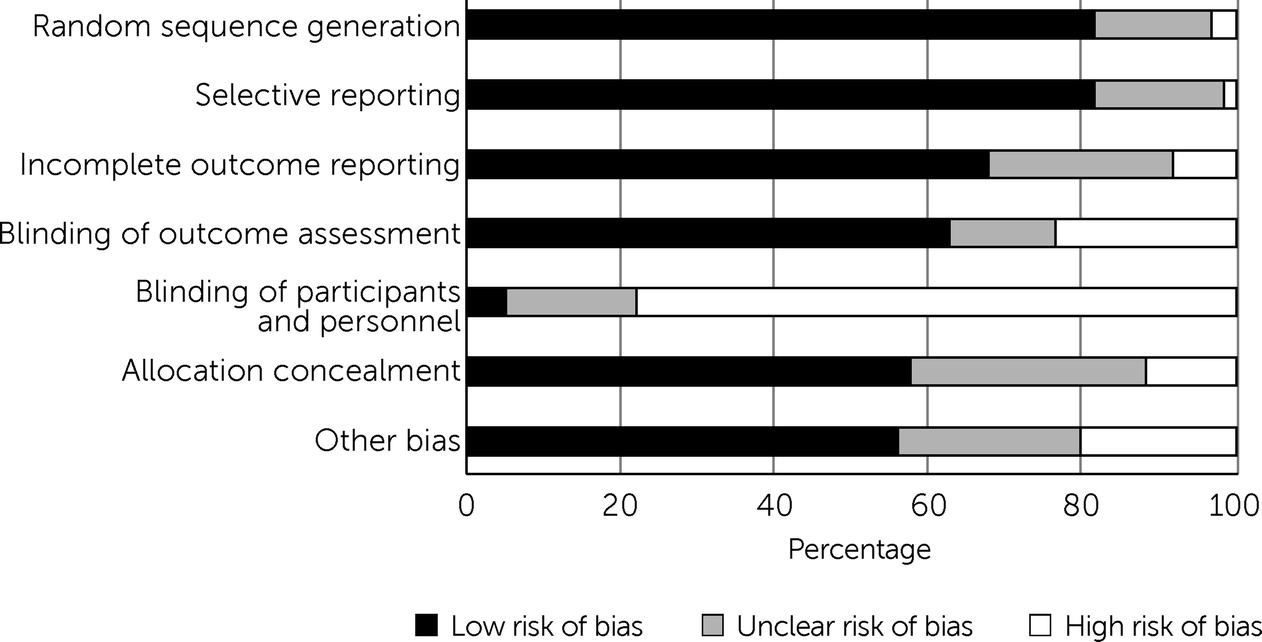

Figure 2 shows the summary results of the risk-of-bias assessment among the included RCTs (63 studies). Most (N=48, 76%) had a high risk of performance bias due to a lack of blinding of participants and personnel to the treatment condition. This bias risk was expected, because a similar pattern was observed in the previous systematic review and because it is not feasible for study participants to be blind to treatment condition in many interventions involving mental health care. On the basis of the Cochrane tool for risk-of-bias guidelines (

28), we found that 53 articles had a high risk of bias, eight had an unclear risk of bias, and only two had a low risk of bias.

Meta-Analysis of the Effectiveness of Integration for Depression Care

Fifty-six studies from 54 articles (

29–

82) evaluated the effectiveness of integration of depression care into primary care. A total of 14,696 patients were in the treatment group, and 14,192 patients were in the control group. The most frequently evaluated primary outcome was level of depression severity of patient participants. The studies applied interventions such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), problem-solving therapy, interpersonal psychotherapy, supported self-management, and psychosocial support. Fifty of the studies included a comparison group that received usual care or enhanced usual care. A forest plot (see the

online supplement) shows the effects on depression outcomes in these studies. The overall random effect size was 0.28 (95% CI=0.22–0.35). This effect size indicates that, on average, integration of depression care into primary health care improved depression outcomes. We found large heterogeneity in our analysis (I

2=96%), indicating significant variation in outcomes across studies.

Thirty-seven articles reported that integration significantly improved depression outcomes. For example, in China, Chen et al. (

38) evaluated a collaborative intervention for depression care management for older adults and reported a particularly large integration effect of 1.18 (95% CI=1.07–1.28). Sixteen articles reported statistically nonsignificant results. Of these, one study found that integration had a negative but nonsignificant impact on depression outcomes; in Indonesia, Anjara et al. (

63) implemented mental health training for general practitioners and nurses at 14 community health centers and reported a negative effect of this training of −0.01 (95% CI=−0.13 to 0.10) on depression outcomes.

Meta-Analysis of the Effectiveness of Integration for Alcohol Use Disorder Care

Eighteen articles reporting on eighteen studies (

57,

62,

69,

77,

83–

96) evaluated the effectiveness of integrating alcohol use disorder care into primary care. The most frequently evaluated primary outcome was alcohol consumption of participating patients. The intervention groups in the included studies most commonly received motivational interviewing, brief interventions, and CBT. Sixteen of the studies had a comparison group, which received treatment as usual or enhanced usual care. Overall, 4,501 patients were in the treatment group, and 4,125 patients were in the control group. A forest plot (see the

online supplement) shows effects on alcohol use outcomes in these studies. The overall random effect size was 0.17 (95% CI=0.11–0.24), indicating that, on average, integration of alcohol use disorder care into primary care improved alcohol use outcomes. We again found large study heterogeneity in our analysis (I

2=87%).

Nine (

83,

84,

86–

88,

91,

93–

95) of the 18 articles reported that the effectiveness of integration in improving alcohol use outcomes was statistically significant. For instance, Harder et al. (

94) tested a mobile phone–delivered motivational interviewing intervention among adults with alcohol use problems in rural Kenya. The authors reported a promising effect size of 0.51 (95% CI=0.37–0.64) of this intervention. The nine remaining articles (

57,

62,

69,

77,

85,

89,

90,

92,

96) reported statistically nonsignificant results. In India, Prabhakaran et al. (

77) evaluated the effectiveness of mWellcare, a mobile health integration for five chronic conditions (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, tobacco use, alcohol use, and depression) and reported that mWellcare had an effect size of 0.01 (95% CI=–0.03 to 0.04). In Thailand, Assanangkornchai et al. (

89) compared the effectiveness of WHO ASSIST, a screening survey for alcohol misuse, followed by a formal brief intervention or simple advice and reported an effect size of 0.01 (95% CI=−0.21 to 0.23).

Models of Integration

Seventy-four studies from the previous review and the present study were categorized by using the previously established six models of integration. The models tested in this study comprised one or more strategic intervention options; each option represented an active enhancement to primary care affecting workforce capacity, information management, or daily care. The types of integration models are described in

Table 2. Eight studies met criteria for model 1 (

32,

43,

47,

52,

63,

75,

77), which includes only general training for lay health workers or primary health workers or both. Thirty-three studies met criteria for model 2 (

29,

31,

34,

35,

41,

42,

45,

46,

51,

53–

56,

58–

60,

62,

64–

66,

68–

70,

72,

73,

80–

82,

84–

86,

93), providing lay health workers general training (similar to model 1), with the addition of specific training in delivering interventions. Seventeen studies met criteria for model 3 (

40,

44,

48,

67,

71,

74,

76,

83,

87–

92,

95,

96), including general training in addition to specific training for delivering interventions for primary health workers (nurses and general practitioners). One study met criteria for model 4 (

37), which provided primary health workers consultation services from a mental health worker. Five studies met criteria for model 5 (stepped care) (

30,

33,

39,

61,

78), which matched treatment intensity with patients’ needs. Eight studies met criteria for model 6 (collaborative care management) (

36,

38,

49,

50,

57), which uses case managers or coordinators and strategic data management to improve patient outcomes.

During preparation of our review, we identified a new model of integration that uses mental health care embedded in primary care settings. Unlike the other models of integration, model 7 included trained mental health professionals delivering mental health care services in the primary care centers; two studies met criteria for model 7 (

79,

94).

Table 1 describes the various strategic intervention options used in each type of integration model.

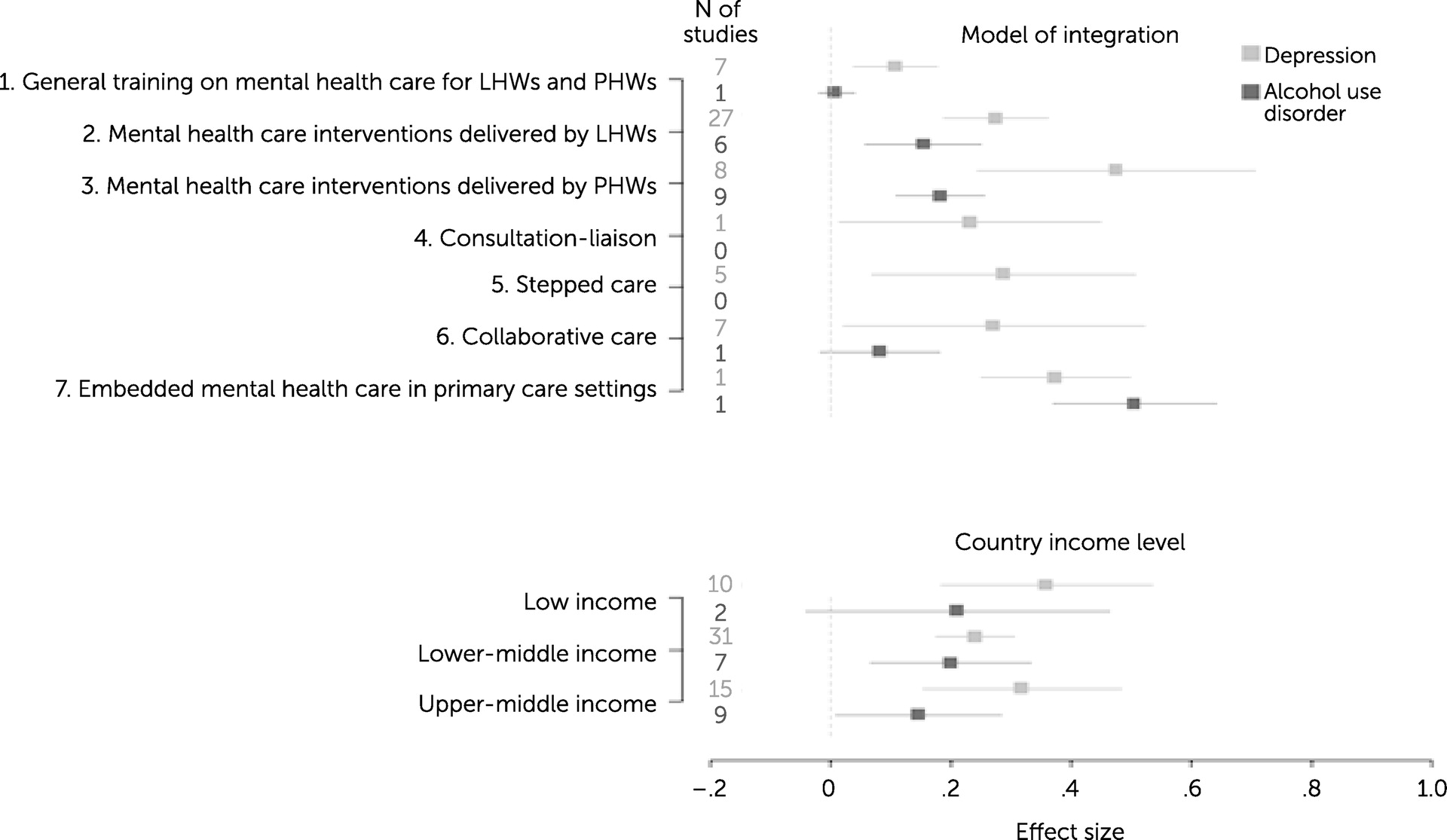

Our analysis of the impact of the type of integration model on effectiveness revealed that model type had a nonsignificant linear effect (β=0.016, p=0.054) on depression outcomes. However, we also observed that the overall effect significantly differed among the different integration models (p<0.001). A forest plot (

Figure 3) shows the effect sizes for the models of integration; models 3 and 7 had much higher effect sizes, compared with model 1. Similarly, integration model type had a nonsignificant linear effect (β=0.042, p=0.080) on alcohol use outcomes, but the differences in the effects among groups were statistically significant (p<0.001). For instance, model 2 was found to yield better outcomes than model 1.

Income Level

We also tested the relationship between country income level and the effectiveness results. We found that the income level had a nonsignificant negative linear effect (β=−0.012, p=0.084) on depression outcomes, indicating that studies set in higher-income countries reported smaller effects of mental health integration on depression outcomes. Similarly, studies showed a similar negative nonsignificant linear trend (β=−0.037, p=0.070) of country income level on alcohol use outcomes. The forest plot in

Figure 3 shows the effect sizes for country income level.

Additional Subgroup Analyses

We also conducted subanalyses to investigate whether effect sizes differed by study design and control group type (see the online supplement). We observed differences in effect sizes among study design types. Studies that used RCTs reported smaller effect sizes than did studies that used quasi-experiments. However, we found a very high heterogeneity within study design types. In addition, the type of control group used (treatment as usual, enhanced usual care, or no control) had no differential effects. The heterogeneity within each type of control group was also very high.

Publication Bias

We used funnel plots to examine publication bias in the results of the meta-analysis. Among studies on depression care, we noted an asymmetric distribution (see the online supplement); a cluster of studies that reported smaller than average effect sizes had very small standard errors, and the plot also revealed that studies with larger standard errors tended to report larger effect sizes. Studies on alcohol use disorder care showed a similar asymmetry in funnel plots (see the online supplement). These findings indicate that possible publication bias may have affected this meta-analysis.

Discussion

This meta-analysis included 74 studies evaluating the effectiveness of integrating depression and alcohol use disorder care into primary care centers in LMICs. The findings indicate that such integration has an overall effect size of 0.28 for depression and 0.17 for alcohol use disorder. These effect sizes are small to medium and similar to those reported in previous meta-analyses of depression and alcohol use disorder interventions (

97–

100). Patients in integration interventions have overall better outcomes than those who receive care as usual. The qualitative synthesis conducted in our previous review resulted in similar findings of the effectiveness of various integration models on depression and alcohol use disorder care (

19). Previous research supports our findings that interventions delivered by nonspecialist health care workers in LMICs may improve depression outcomes and may decrease alcohol consumption among persons with alcohol use disorder (

17,

101).

Although the meta-analysis results supported the overall effectiveness of integration of depression and alcohol use disorder care into primary care, 16 of 56 studies reported that integration did not significantly decrease depression severity, and nine of 18 studies reported that integration did not significantly improve alcohol use outcomes. The most commonly reported reason for nonsignificant results was the effect of follow-up assessments, which occurred periodically during the intervention. Even when patients do not receive an integrated intervention, asking them to complete assessment questions as a way of monitoring their symptoms and behavior could itself improve depression and alcohol use disorder symptoms. Another reason for nonsignificant results that was discussed in many of these studies is the natural course of mild and moderate disorders. Some studies assessed participants with mild-to-moderate severity of depression and alcohol use disorder; over time, patients may naturally recover or exhibit spontaneous remission without an intervention. Finally, a few articles stated that the Hawthorne effect may have affected results among providers and patients. For instance, providers in the comparison arm may change their behavior and deliver better-quality care to patients, leading to a null result.

This review included studies that evaluated various models of integrated depression and alcohol use disorder care in LMICs. We propose an updated typology of models of depression and alcohol use disorder care integration that is based on the typology in our previous review (

19) and a new model of integration, resulting in seven models (

Table 2). This typology of models can contribute to the literature on depression and alcohol use disorder care integration strategies. The models differ in complexity, cost, and required resources. Additionally, this typology is intended to help policy makers and health care managers determine which models of care are most suitable for their targeted setting and population, considering critical variables such as human and financial resources, technology availability, and geographic accessibility, among others (

18).

This analysis disclosed that the type of integration model did not have a significant linear impact on the effectiveness of integration of depression and alcohol use disorder care into primary care. However, we found that effect sizes for depression and alcohol use outcomes widely differed between certain types of models. Despite this finding, we note that some model types, particularly models 4 and 7, had very small sample sizes. Additionally, we are hesitant to compare the effect sizes among model types, because we did not account for the baseline characteristics of the study participants in this analysis. For these reasons, it remains unclear which specific model types are more beneficial for depression and alcohol use disorder care. Rather, our findings emphasize that the most effective integration model for a particular setting may be the one deemed most feasible and sustainable (particularly given the possibility of increased direct costs [

19]). Research analyses with more robust comparisons are needed to clarify the role of integration model in the effectiveness of mental health interventions.

In our analysis, we found that country income level did not play a significant role in the effectiveness of integration on depression and alcohol use disorder outcomes. Our results indicate that integration models implemented in higher-income countries tended to have smaller effect sizes, compared with treatment as usual or enhanced usual care. A potential explanation for this finding is that higher-income settings may have better preexisting mental health services and outcomes, and thus outcomes are less affected by depression and alcohol use disorder care integration. However, the linear trend of income level was statistically nonsignificant, and more research is needed on the impact of income level on integration.

Unsurprisingly, we observed high heterogeneity of study results in our meta-analysis. Even when we conducted subgroup analyses on randomization and types of comparison groups, we still observed high heterogeneity. We computed the I2 estimates, but the limitations of this procedure should be considered. Several factors could contribute to the observed high heterogeneity. For instance, differing levels in the capacity of health systems, differences in the ability of a system to deliver care effectively and in a timely manner to those who need care, and differences among countries and regions within a country likely contributed to differences within and among the results of the reviewed studies. However, differences in health system capacity are not easily quantifiable. Although we lack an effective way to quantitatively account for health system capacity, we propose that the relationship between capacity and the type of interventions implemented is relevant. For instance, health care systems with high capacity have a higher level of organization, which allows for nearly optimal care delivery. For this reason, the higher capacity level a health system has, the lower the impact an integrated intervention may have.

The variety of different methods of reporting results could also have been a source of heterogeneity. Moreover, the included studies varied greatly in terms of the populations studied, baseline characteristics, and intervention setting. Because of inconsistent and limited reported data on characteristics (i.e., gender, comorbid conditions, and socioeconomic status), we could not conduct analyses to account for these variables. Additionally, we expected high heterogeneity because the effect size of each integration model was relative to that of the control or treatment-as-usual arm of each trial, which varied among settings. Therefore, decision makers should consider the baseline characteristics of the health care system in which they are working when selecting integration models. Finally, the intervention itself could be a source of heterogeneity, because this study included all types of integration approaches in primary care interventions for depression and alcohol use disorder. We attempted to handle the wide variety of interventions in the meta-analysis by applying a typology of integration models and conducting a meta-regression analysis by types of models. Future studies could conduct meta-analyses that are restricted to specific intervention types.

Conducting an extensive search via the Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials and other databases to identify as much relevant literature as possible can reduce the risk of publication bias. However, when we analyzed publication bias in the funnel plots, we observed asymmetry between the sample size of each study and the size of the standard error in the intervention effect, which could have several possible causes (

102). Publication bias, selective outcome reporting, and selective analysis reporting may have led to this asymmetry. We note evidence indicating that articles reporting statistically significant “positive” results have a higher chance of being accepted for publication, published quickly, published in high-impact journals, and cited by others (

102–

104). This is important to consider, because it is known that publication bias can distort the findings in systematic reviews and meta-analyses (

105). However, we caution that asymmetric funnel plots do not prove but only suggest the presence of publication bias.

This review and meta-analysis had several limitations. First, the studies implemented depression and alcohol use disorder care integration into primary care in diverse settings, but we extracted and summarized data only on country income and level of rurality. Heterogeneity within countries (i.e., geographical accessibility and resources) is a possible limitation, and the effect sizes should be interpreted in light of this potential heterogeneity. Second, 11 of the included studies did not have adequate comparison arms and had quasi-experimental designs. Inadequate comparison arms can produce misleading results. Third, this meta-analysis did not investigate the cost and cost-effectiveness of depression and alcohol use disorder care integration studies and excluded articles that evaluated only cost-effectiveness. Finally, this study excluded articles in languages in which our authors were not proficient, which is relevant given that researchers in LMICs likely write and publish papers in many other languages than those included in this analysis.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, this study used descriptive and quantitative synthesis to gain important insights into the value of depression and alcohol use disorder care integration into primary care in LMICs. The meta-analysis findings highlight the diverse range of depression and alcohol use disorder integration studies, and articles in this field are likely to continue to increase, especially in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and its impacts on mental health globally. Further updates to this study may be needed to provide more insight into the relative effectiveness of the different types of integration models in different types of settings. Additional contributions to the evidence base will help improve our understanding of how best to implement mental health integration in primary care. Future research should explore the optimal mix of services for mental health care in LMICs and evaluate evidence of cost-effectiveness of mental health integration in primary health care districts and clinics. This review revealed evidence that integrated interventions in primary care can improve depression and alcohol use disorder outcomes, although it is important for policy makers to ensure that several factors, such as existing infrastructure, personnel, and resources, are considered when integrating depression and alcohol use disorder care into primary care.