Self-directed care (SDC) is a treatment model in which recipients self-manage funds designated for provision of services. The model was originally developed for the long-term care of Medicaid beneficiaries, including people with severe physical and developmental disabilities and elderly individuals (

1). Recent evidence on its use to promote mental health recovery shows that the model improves individual-level outcomes with budget neutrality, that is, costing no more than traditional service delivery (

2). Studies of SDC participants have found enhanced functioning and community tenure (

3,

4), improved employment and residential outcomes (

5), fewer unmet needs for personal care (

6), increased outpatient and rehabilitation service use (

7), and enhanced coping mastery and symptom reduction (

8). However, most research has focused on Medicaid beneficiaries (

9) rather than on uninsured public mental health service recipients with low incomes, an especially vulnerable group (

10). The purpose of this study was to assess the effectiveness of SDC for this population by measuring its impact on participant outcomes, service utilization and costs, and user satisfaction.

The SDC model we tested is grounded in self-determination theory (

11,

12), which posits that behavior change in the health domain occurs when people are internally motivated, interact with providers who support their autonomy, and increase their perceived competence for self-management (

13–

16). Active ingredients include providing information about a variety of treatments and services, acknowledging participants’ feelings, and enhancing choice by giving people control over funds for service delivery. Staff members, called brokers, help participants develop recovery plans and budgets and secure services and supports (

17).

Our target population, known as “medically indigent” (

18), consisted of adults with mental illness and low income who lacked health insurance but did not qualify for Medicaid, Medicare, or private health insurance. They comprise 28%–31% of persons served by state mental health authorities (

19,

20), and an estimated 1.5 million nationwide have serious mental illness (

10). These individuals are likely to be in poor health, with multiple comorbid conditions (

21,

22). As many as 40% are unemployed or out of the labor force (

10), and severe financial strain exacerbates their psychiatric conditions (

21). This high-need group may benefit from SDC’s service flexibility in the context of the model’s budget neutrality. Therefore, we tested the null hypothesis of no difference between SDC and services as usual in improving perceived competence for mental health self-management, met and unmet needs, recovery, and employment outcomes. Next, we tested the null hypothesis of no difference in service utilization and costs between the two study conditions. Finally, we evaluated SDC participants’ satisfaction with the program.

Methods

This study involved collaboration between researchers at the Center on Mental Health Services Research and Policy at the University of Illinois Chicago and a nonprofit public behavioral health managing entity (BHME) named Lutheran Services Florida. The latter is one of seven regional BHMEs in Florida, providing administration, management, oversight, and support for a network of provider agencies delivering state-funded behavioral health services exclusively to medically uninsured individuals in 23 counties. As a nonprovider organization, Lutheran Services Florida offered a site for the SDC program where participants would feel free to choose services from any provider organization. The program operated in two counties from January 2018 to April 2020.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria were being ages 18–60 years; having serious mental illness, as defined by federal Public Law 102–321 (

23) and state statute; enrollment in an agency overseen by the BHME; and understanding spoken English. Exclusion criteria included cognitive impairment (preventing informed consent); representative payeeship or court-mandated treatment or residential treatment (because the model requires choice in services and expenditures); recent uncontrolled substance use (to avoid misuse of funds); and recent violent behavior (because brokers and participants met alone in the community).

Study Procedures

Study recruitment was conducted by local BHME staff, supervised by university researchers, from September 2017 to February 2019. From administrative data, the BHME identified potentially eligible individuals receiving services at participating agencies. After onsite review of case files confirmed eligibility, these individuals were contacted by U.S. mail and telephone and were invited to participate.

Telephone interviews were conducted at baseline and at 6 and 12 months postbaseline. All interviewers were blind to respondents’ study condition. Random assignment occurred at the end of baseline interviews by using a randomly generated allocation sequence programmed into computer-assisted interviewing software. The study was approved by the University of Illinois Chicago Institutional Review Board.

Traditional mental health services were funded by allocations from the state behavioral health authority to the BHME. Discretionary funding from these allocations paid for nontraditional services and goods named in SDC participants’ individual budgets. A local nonprofit organization served as the program’s fiscal intermediary, supplying brokers with credit cards and overseeing adherence to standard fiscal practices.

SDC Intervention

Each participant’s annual budget was $4,000, which was the BHME’s average annual per-person cost for behavioral health services, excluding inpatient treatment, crisis services, and medications that remained available through regular channels. Participants met with brokers for program orientation and to review their current life situations and their use of behavioral health services in the past year.

This review culminated in participants’ choice of recovery goals and associated budgets, including traditional and nontraditional purchases. Nontraditional purchases included service substitutions (e.g., using Uber for transportation instead of an agency van), ancillary services (e.g., medical or dental care), private-sector providers, and goods directly related to recovery goals (e.g., eyeglasses, laptops, and work uniforms). Budgets required approval by the program supervisor. Brokers and participants met quarterly to review spending and progress toward recovery goals and to create budgets for the subsequent quarter.

Services as Usual

Participants in the control group received services available to uninsured adults meeting Lutheran Services Florida’s diagnostic, income, and other admissions criteria. Services included medication management, assessment, case management, skills training, peer services, psychotherapy, substance use services, and residential treatment. These services were delivered by community behavioral health agencies located in two regions of Florida.

Measures

The primary outcome was participants’ feelings of competence in managing their mental health, assessed with the four-item Perceived Competence Scale (

24). Secondary outcomes were met and unmet needs across multiple life domains, such as psychological distress, general health, and finances, assessed by using the 22-item Camberwell Assessment of Need Short Appraisal Schedule (

25); perception of service providers as supporting recipients’ autonomy, assessed with the six-item Health Care Climate Questionnaire (

26); and perceived level of recovery from mental illness, measured by using the 41-item Recovery Assessment Scale (RAS) (

27), including total and subscale scores. Given previous research (

5,

8), we also assessed the rehabilitation outcome of employment by using the U.S. Department of Labor definition as any work for pay or profit during a reference period. Finally, a set of items assessing satisfaction with the SDC program was administered at the final interview.

Lutheran Services Florida information technology staff extracted service utilization and cost data from electronic administrative records maintained for reporting to the state behavioral health authority. The nature and costs of nontraditional services and goods were extracted from SDC program records maintained by brokers.

Statistical Analysis

We tested the success of random assignment with chi-square and t tests to confirm the absence of statistically significant differences between study conditions on measured baseline characteristics. Individual-level outcomes were tested by using random effects linear and logistic regression models (RRMs). Features typical of longitudinal data, including serial correlation, baseline heterogeneity, missing observations, and time-varying measures (

28), were addressed by using repeated measures covariance specification, random intercepts, inclusion of all available data, and a linear measure of time. Each model included random intercept, study condition, time (measured as baseline, midpoint, and follow-up), and a study condition × time interaction. No additional covariates were included, given the success of random assignment, described below. Standardized effect sizes equivalent to Cohen's d were computed from study condition × time interactions, number of follow-up time points, and pooled standard deviations at follow-up (

29,

30) to assess the magnitude of the intervention effect, interpreted as small (0.2–0.4), medium (0.5–0.8), or large (>0.8) (

31).

For analysis of service data, the percentage of participants in each condition using mental health services and mean per-person service costs by service type were examined descriptively. Utilization differences by study condition were analyzed with chi-square tests, and differences in costs were analyzed by using generalized linear models with negative binomial distribution for overdispersed count data (

32,

33). Finally, descriptive statistics were used to assess satisfaction with the program and services. Data were analyzed in SPSS, version 25.

Study Retention

Forty-five individuals consented to participation and were randomly assigned to either the intervention (N=22) or control (N=23) condition (a CONSORT diagram is available in the online supplement to this article). One participant in the intervention group and two in the control group were later excluded because of ineligibility or a request to withdraw from the research, resulting in a sample of 42 individuals. Most participants (N=39, 93%) completed at least one follow-up assessment, and 83% (N=35) completed the final 12-month assessment. Attrition did not differ significantly by study condition.

Model Fidelity

The Self-Directed Care Fidelity Scale (

8) was administered to measure adherence to the model in staffing, management, and service delivery. At 2-day site visits in October 2018 and February 2020, a team of three external auditors interviewed brokers, participants, fiscal intermediary staff, and community service providers; reviewed randomly selected case files; analyzed written policies and procedures; and observed interactions between SDC staff and participants. Results were shared with program staff and managers after each visit. Fidelity increased from a baseline score of 91, representing fair fidelity, to a final score of 97, representing good fidelity.

Results

Baseline Characteristics and Multivariable Analysis of Participant Outcomes

Participants in the two study conditions did not differ significantly (p<0.05) on measured baseline characteristics (

Table 1).

Table 2 presents the results of the RRM, including effect sizes for the magnitude of the intervention’s impact over time. Participants receiving SDC had significantly greater improvement in perceived competence for managing mental illness than did participants in the control group. The observed effect size of 0.93 indicated a considerable impact of the intervention on instilling confidence in self-management ability. Participants receiving SDC reported significantly more met needs and significantly fewer unmet needs over time, compared with those in the control group. Effect sizes for these two outcomes indicated that SDC had a moderate impact on addressing participants’ needs.

SDC participants’ ratings of the degree of autonomy encouraged by their service providers increased over time; these increases were significant compared with the control group, indicating a moderate impact of SDC on creating a service delivery environment that supported patients’ autonomy. Additionally, compared with those assigned to the control condition, participants receiving SDC improved significantly over time in the RAS subscale that measured feelings of being dominated by psychiatric symptoms, with an effect size indicating a moderate impact on dealing with symptomatology. The total recovery score and remaining subscales did not show statistically significant differences between the two groups. Finally, participants receiving SDC were more likely than those in the control group to be employed over time (SDC: baseline=38%, follow-up=53%; control: baseline=29%, follow-up=38%), with a moderate effect size of the intervention.

Service Use and Costs

Table 3 shows the proportion of participants using behavioral health services and the results of negative binomial regression analyses testing for the effects of study condition on total and individual service costs. The two groups did not differ significantly in the proportion of participants using any behavioral health services: 100% of those in the SDC group and 86% of those in the control group used one or more services. Participants receiving SDC had slightly higher mean total costs than those in the control group ($2,570 vs. $2,270, respectively), but this difference was not statistically significant.

The two groups did not differ significantly in the proportion of participants using any traditional behavioral health service (SDC=95%, control=86%). Participants receiving SDC had somewhat lower mean costs for traditional services ($1,624), compared with those in the control group ($2,270), but this difference was nonsignificant. No significant differences were found in the proportion of participants using specific types of services nor in the costs of individual services, except for lower diagnostic service costs for SDC versus treatment as usual.

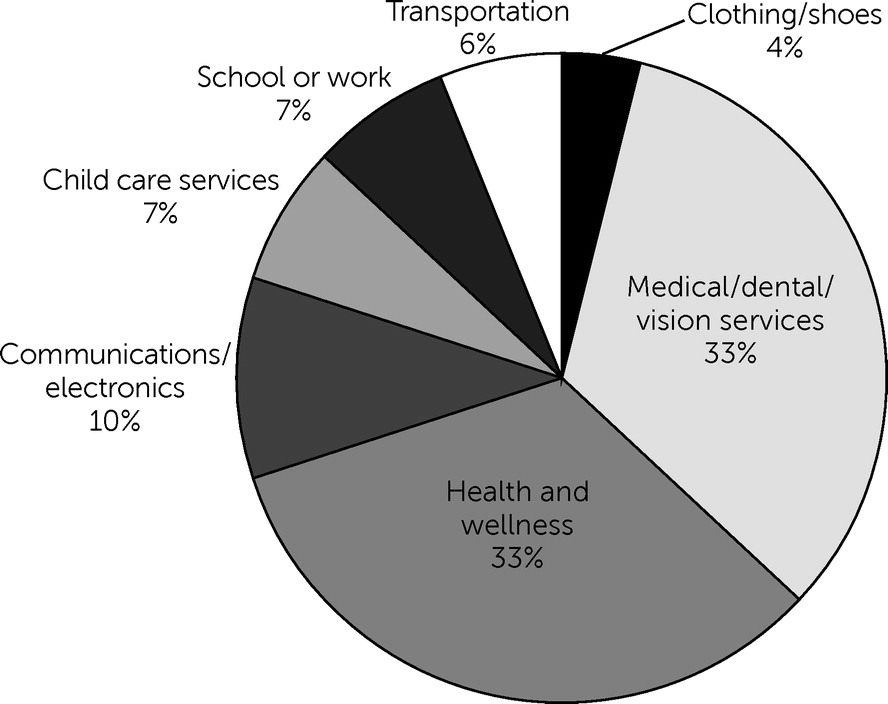

Nontraditional Services and Material Goods

Figure 1 shows the types of nontraditional services and goods purchased through individual budgets. Most frequent were medical, dental, or vision services at 33% ($6,489) and health- and wellness-related purchases at 33% ($6,465) (e.g., gym membership, acupuncture, and medical supplies). Other expenditures included communications and electronics expenses at 10% ($1,898), child care services at 7% ($1,412), school or work expenses at 7% ($1,481), transportation at 6% ($1,255), and shoes and clothing at 4% ($875). (All percentages are calculated on the basis of total dollars spent on these services and goods [$19,875].)

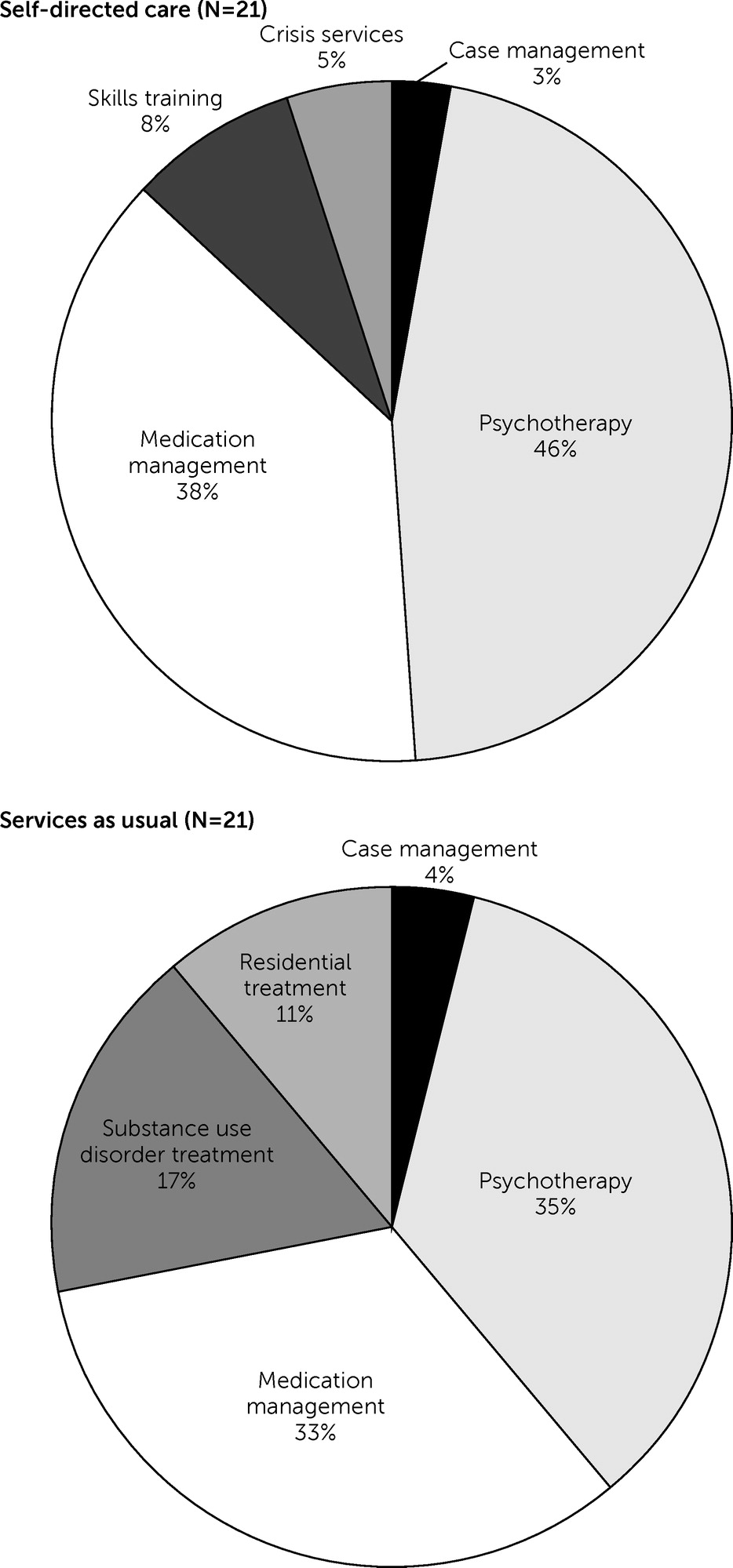

Traditional Mental Health Service Expenditures by Study Condition

Figure 2 presents individual mental health service expenditures as proportions of total expenditures, by study condition. The SDC condition had a higher proportion of program expenditures than the control condition for psychotherapy (46% [$15,842 of $34,104] vs. 35% [$16,477 of $47,670]), medication management (38% [$12,789 of $34,104] vs. 33% [$15,755 of $47,670]), skills training (8% [$2,870 of $34,104] vs. 0%), and crisis services (5% [$1,557 of $34,104] vs. 0%) and a lower proportion of expenditures for substance use disorder treatment (0% vs. 17% [$7,879 of $47,670]), residential treatment (0% vs. 11% [$5,462 of $47,670]), and case management (3% [$976 of $34,104] vs. 4% [$1,926 of $47,670]). Overall, expenditures on traditional service types were similar across the two conditions.

SDC Satisfaction

Of participants receiving SDC who completed follow-up assessments (N=19), most (N=14, 74%) reported being “very” or “somewhat” satisfied with the help they received, with 21% (N=4) “somewhat dissatisfied,” and 5% (N=1) “very dissatisfied.” Almost three-quarters (N=14, 74%) reported “a lot” of satisfaction with purchases, 16% (N=3) “a little,” and 11% (N=2) “not at all satisfied.” When asked to compare their mental health services before versus during the SDC program, 68% (N=13) said that their services were better, with the remainder (N=6, 32%) reporting that services were about the same. Just over half (N=10, 53%) of these participants reported making “a lot” of progress in achieving their goals, 37% (N=7) “a little” progress, and 11% (N=2) no progress.

Discussion

Compared with those receiving services as usual, participants receiving SDC had significantly greater improvement in the primary outcome of self-perceived competence in managing their mental health. In addition, they reported significant increases in the degree of autonomy encouraged by their care providers, which also exceeded levels reported by those in the control group. In self-determination theory, autonomy-supportive health care environments are deemed essential for promoting lasting change in health behavior (

34,

35). Our results contribute to the mental health SDC evidence base by suggesting that these environments support people’s autonomous motivation to persist in achieving recovery goals (

14,

36,

37). Moreover, our finding of increased perceived competence confirms previous SDC research showing that such competence is a necessary precursor to self-management skill acquisition and behavior change (

38,

39).

We hypothesized that SDC’s autonomy-supportive environment, greater service choice, and increased perceived competence would improve rehabilitation outcomes, such as employment. We found a higher employment rate, with more than half of SDC participants (53%) working by the study’s end, compared with those in the control condition (38%). We observed that many nontraditional purchases were work related, such as professional fees, child care, transportation, and electronics expenditures.

Like others (

6), we expected SDC to meet a wide range of participants’ needs. We observed significant decreases in unmet health and social needs and increases in addressed needs. The model’s ability to offer individually tailored treatment and rehabilitation options while increasing feelings of competence in using them may be well matched to the diverse and changing needs of uninsured adults recovering from disabling psychiatric conditions.

A final outcome we anticipated was that participants receiving SDC would experience greater recovery from mental health conditions than those receiving services as usual. We observed significant increases in recovery, indicated by reductions in feelings of being dominated by psychiatric symptoms. This outcome is important for individuals coping with residual symptoms that may interfere with valued goals, such as building satisfying relationships and community participation (

40,

41). However, we did not find significant increases in total RAS score or other subscale score. It is possible that participants’ relatively short 1-year exposure to SDC services did not allow for additional changes.

Importantly, these superior outcomes were achieved in the context of budget neutrality. Our intent-to-treat analysis found no significant differences in total average service costs between the two study conditions. Services individually chosen and used by SDC participants cost no more than services delivered by community agencies directly funded to provide a negotiated set of treatment options. In terms of specific service types, no significant differences were found between the two study conditions in costs of most individual services, except for diagnostic assessment, where SDC participants spent less on average than participants in the control group.

When given a choice, SDC participants continued to use traditional services such as medication management and psychotherapy. This finding mirrors results of a study in Utah, which reported increased use of mental health outpatient and rehabilitation services after individuals entered SDC (

7). Interestingly, our participants maintained use of traditional services, yet their total expenditures were budget neutral on average, meaning they offset the costs of their nontraditional services. This pattern is similar to that observed for an SDC program in Pennsylvania, where people banked their reduced traditional service funds for use on nontraditional purchases (

42).

Descriptive analysis of nontraditional purchases revealed that the two most common ones were for needs related to medical, dental, or vision care and those related to health and wellness. This finding is noteworthy given our population’s lack of insurance coverage for general medical care, poor self-reported general medical health, and prevalent comorbid conditions. The SDC model may be well suited to those with serious mental illness caught in the so-called Medicaid coverage gap, who lack a pathway to health insurance yet are managing multiple chronic conditions (

43,

44).

Other nontraditional purchases reflect participants’ severely constrained financial circumstances, which prevented access to communication and electronics devices, child care, work- and school-related necessities, and transportation. Although they are similar to the nontraditional purchases reported in previous studies of mental health SDC (

4,

8,

45), these purchases also reflect the situations of individuals with low income who do not qualify for programs such as Medicaid yet face formidable challenges related to social determinants of health, such as poor local labor markets and lack of public transportation. These findings suggest that the offerings of traditional mental health systems are inadequate to meet the full range of recovery needs of people who do not qualify for subsidized health insurance and income support programs (

3).

This study had several limitations. Its small sample may limit generalizability of the findings. Moreover, although randomization was successful, other unmeasured factors may have influenced study outcomes. Additionally, although service use was high in both study conditions, we did not measure participant engagement in services, which might have influenced outcomes. Also, we were unable to compare administrative costs of the two conditions and could not capture the occurrence or costs of any services that were delivered outside the state system. Finally, some of the study’s outcomes were measured through self-reports and therefore were potentially biased because of factors such as poor memory or social desirability.

Conclusions

Use of the SDC approach with uninsured adults with serious mental illness yielded superior outcomes compared with the traditional system of community agencies and did not result in higher service delivery costs. Given indigent care’s strict requirement to ensure optimal use of resources dedicated as a last resort for care (

46), these findings point to the need for further study of this model on a larger scale in behavioral health systems serving uninsured individuals with low income. Research is also needed to explore the ways that use of goods and nontraditional services in this model leads to positive rehabilitation and recovery outcomes for this highly vulnerable group.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge contributions from the following individuals and organizations: Katherine Kesler, Sarah Davidson, Jenaye Nolan, Samantha Zarnes, Zachary Jimison, Katherine Perez, Paige Klucina, Steven Rankin, Gene Costlow, Wesley Evans, Erin Whitaker-Houck, Jennifer Spaulding-Givens, Brandy Ruckdeschel, Samuel Shore, Volunteers of America of Florida, Florida Department of Children and Families, Florida SDC Circuit 20, Florida Self-Directed Care Program District 4, Aging True, and the University of Illinois Chicago Survey Research Laboratory.