For patients with a chronic psychotic or affective disorder, LAIAPs have some advantages over oral antipsychotic regimens. Interruptions in antipsychotic therapy are associated with deterioration in function, psychiatric hospitalization, and possible community disruption (

6,

7). Patients with a chronic psychotic or affective disorder who use LAIAPs are up to 20% less likely to discontinue medications than those taking oral regimens (

8). A recent meta-analysis reported that patients with schizophrenia had nearly twice the odds of medication adherence (≥80% days adherent) when using an LAIAP than when using oral regimens (

9). Because the use of LAIAPs provides greater privacy than use of oral antipsychotics and does not require adherence to daily pill regimens, LAIAPs are also associated with less stigma among some patients (

10,

11). Use of LAIAPs is also associated with decreased rates of psychiatric hospitalization and emergency department utilization (

9,

12). Correspondingly, growing research supports the efficacy of using LAIAPs early in the disease course, including after first-episode psychosis (FEP) (

13–

15).

In this study, we sought to quantify prescription patterns of LAIAPs by U.S. outpatient mental health care service providers. Given the role of LAIAPs in improving outcomes, increasing LAIAP utilization is an important part of psychiatric care. Identifying gaps in LAIAP prescription may reveal opportunities for innovation to better meet the needs of patients. Our objectives were to determine the percentage of U.S. outpatient mental health service providers prescribing LAIAPs, identify the most commonly prescribed LAIAPs among outpatient mental health care service providers, and ascertain the factors associated with the likelihood that an outpatient mental health service provider prescribes LAIAPs.

Discussion

A robust body of evidence supports the benefits and safety of LAIAPs for patients with chronic psychotic or affective disorders such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (

9,

12,

16,

26–

29). LAIAPs are an essential component of the array of interventions that improve quality of life and outcomes for people with such disorders (

12). Prescription of LAIAPs in outpatient settings is important for maintaining stability of treatment and to promote recovery and quality of life for patients who need chronic antipsychotic therapy.

Overall, a low percentage (30.6%) of outpatient mental health care service providers prescribed LAIAPs, and only 51.6% of the outpatient facilities prescribing any antipsychotics (long-acting injectable or oral) prescribed LAIAPs. This finding may be explained by the relatively greater logistic requirements to administer LAIAPs than oral regimens. Prescribing LAIAPs requires available staff time, training, facility space, and administrative time to coordinate schedules and payments (

23,

30). For providers without large populations of patients requiring long-term antipsychotic maintenance therapy, the necessary clinical infrastructure may be impractical.

LAIAPs are also increasingly recognized as an important component of early recovery–oriented care, which may be jeopardized by interruptions in treatment that are more likely with oral antipsychotic regimens (

8,

9,

12–

14,

31,

32). However, we found that only 58.2% of service providers with FEP programs prescribed LAIAPs (

13–

15). Early initiation of antipsychotic therapy that promotes adherence is a crucial component of recovery from early psychosis. This approach not only improves symptomatic stability but also may mitigate long-term neurodegeneration by preventing relapse (

33–

35).

The NIMH has published guidelines detailing coordinated specialty care (CSC) for FEP, which highlight an interdisciplinary approach to supporting patients (

36,

37). An estimated 360 clinics are classified as CSC providers by the NIMH, compared with 1,658 that indicated on the N-MHSS that FEP programming was available (

36,

37). However, the N-MHSS does not inquire about the specific components of this programming, so it is unclear whether providers who indicated their facility offered FEP programming met all CSC criteria, which likely explains this disparity. Importantly, the CSC guidelines do not specifically mention prescription of LAIAPs (

36,

37). As evidence grows supporting the benefits of early initiation of LAIAPs, increasing their availability will be an important area of consideration in designing outpatient services for patients early in their disease course (

13–

15).

We note two interesting findings related to facility type and LAIAP prescription. First, partial hospitalization and day programs were the least likely facility type to prescribe LAIAPs. This level of care may often be transitional for patients being discharged from inpatient psychiatric units before returning to a less-intense psychiatric follow-up schedule. Because some LAIAPs (such as haloperidol decanoate and paliperidone palmitate) require two initiation doses, both of which may not be given in the hospital, the ability to seamlessly continue the injection series in the outpatient setting is paramount to decreasing the risk for decompensation after discharge (

30). Previous work has found that up to 60% of patients who begin an LAIAP series did not receive the follow-up dose as an outpatient (

38,

39).

Second, the percentage of CCBHCs prescribing LAIAPs was relatively low (60.6%). CCBHC models are innovating and expanding and are premised on integration of mental health care, primary care, case management, and peer-support services (

40). Some CCBHCs also have an onsite pharmacy, which may allow for easier administration of LAIAPs. However, implementation of such a model would require training for pharmacists to detect changes in mental health status and timely engagement of psychiatric care providers (

41). Given the inherent multidisciplinary approach of the CCBHC model, these clinics may be opportune outlets to expand LAIAP use with adequate training and communication among all treatment team members (

42,

43).

Another possible strategy for increasing the use of LAIAPs is the expansion of the types of service providers in which patients can receive these medications to include pharmacies (

44). As of 2021, 48 states (excluding New York, Rhode Island, and Washington, D.C.) allowed pharmacists to administer LAIAPs, with eight states requiring a physician-pharmacist collaborative practice agreement (

45). Retail pharmacies are ubiquitous in the United States and already administer immunizations, and the more convenient operating hours of pharmacies may also increase utilization of LAIAPs. Studies of pharmacists and patients, although limited, have reported satisfaction with obtaining LAIAPs from community pharmacies, with good medication adherence; however, additional work is needed to inform further scale-up (

46–

48).

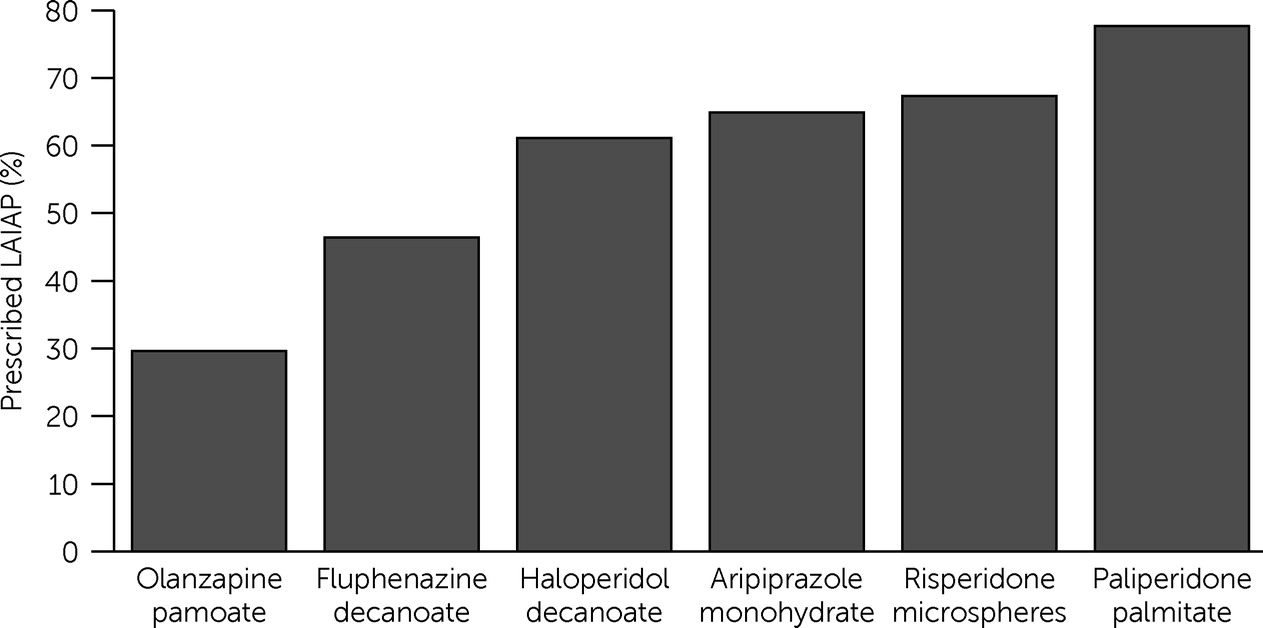

The finding that olanzapine pamoate was the least frequently prescribed LAIAP is not surprising, given the black box warning concerning postinjection delirium and sedation syndrome and the need for a period of monitoring by specially trained clinicians (

49). Thus, the number of outpatient service providers capable of administering this medication is likely significantly lower than for other LAIAPs, which require minimal additional infrastructure to administer.

Although they are effective and safe, LAIAPs are not the sole method of symptom control and relapse prevention for patients with chronic psychotic or affective disorders. Daily oral antipsychotic regimens remain a mainstay in the treatment of patients with these disorders and arguably offer more options for patients, given the greater number of available medications compared with LAIAPs. However, many of the newer oral antipsychotic agents are patented and more expensive. The same is true about the patented LAIAPs, which may be more difficult to obtain for patients because of insurance formulary restrictions and costs. However, we found that many outpatient mental health care service providers that used any LAIAP did not prescribe even relatively inexpensive, generic LAIAPs, such as haloperidol decanoate (39.8% did not use) and fluphenazine decanoate (53.6% did not use) (

Figure 1). This finding may indicate that clinical infrastructure is a greater limiting factor than affordability in the use of LAIAPs.

Finally, although some studies have identified decreased perceptions of stigma about mental illness and treatment among patients using LAIAPs, others have found that some patients have stigmatized views of LAIAPs because of the belief that these medications are reserved for patients with very severe illness (

10,

50). This perception is partially connected to the dissemination of these medications at specialized LAIAP clinics, which further underscores the need to broaden availability of these agents within the community rather than restrict them to specific clinics.

The findings of this study should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. The use of self-reported, cross-sectional survey data is inherently subject to limitations of recall and accuracy in reporting. Although the N-MHSS is distributed to many service providers, it may not be fully inclusive of all outpatient venues for psychiatric care in the United States. Notably, one group excluded from the N-MHSS is private and independent outpatient psychiatry practices, representing an important area of future study regarding use of LAIAPs. Furthermore, the N-MHSS does not quantify the number of patients seeking care at a facility or the number who are prescribed an LAIAP, so an outpatient facility may have been classified as prescribing LAIAPs even if very few of these medications were prescribed to patients. Examination of the facility characteristics associated with greater frequency of LAIAP use would be an interesting and important area for future study. Facility leadership, provider training, and patient education on LAIAPs as a treatment option may also be necessary to improve use of LAIAPs for appropriate patients.

Similarly, in the 2020–2021 N-MHSS, antipsychotic medications were the only specific group of psychotropic agents included; therefore, it was not possible to perform analyses based on whether a service provider prescribed any other psychotropic agents (e.g., antidepressants or mood stabilizers). However, an outpatient facility that prescribes psychotropic medications without also prescribing antipsychotics would likely provide incomplete treatment for mental illness because it would exclude many medication combinations commonly used for pharmacotherapy. Relatedly, data about the availability of samples from pharmaceutical companies or about manufacturer rebates reducing prices for patients who need an LAIAP are not captured by the N-MHSS and may also influence the availability of LAIAPs in the outpatient setting. Further study is needed to better understand the administrative and financial factors that may be limiting LAIAP prescriptions and to inform new service delivery models to increase the use of LAIAPs.

An additional limitation was the exclusion of facilities focused predominantly on substance use, which are not surveyed in the N-MHSS. The companion study, the National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services, does not include questions about whether a facility prescribes LAIAPs for patients with co-occurring substance use and chronic psychotic disorder diagnoses.