According to Thornicroft (

1), case management is the "coordination, integration and allocation of individualized care within limited resources," which includes ongoing contact with one or more identified key personnel. Case management has been implemented in many mental health services in recent years in an attempt to overcome deficiencies in community care, particularly those due to fragmented service systems and lack of continuity of care. Numerous reviews of studies of the effectiveness of case management in mental health services have been conducted (

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22), and the majority have indicated that case management improves outcomes for clients.

However, a review by Marshall and colleagues (

18) found that case management "approximately doubles the number of hospital admissions with little evidence of causing an improvement in mental state, social functioning or quality of life." This finding challenged the prevailing orthodoxy and called the effectiveness of case management into question. The review was conducted as part of the Cochrane collaboration, a network of researchers dedicated to "systematically reviewing the effects of healthcare within their areas of interest" (

23). The collaboration is widely regarded as one of the best sources of evidence about the effectiveness of health interventions. Hence these findings must be regarded seriously.

Case management has been defined in various ways. Solomon (

8), for example, distinguished four types of case management: assertive community treatment, strengths case management, rehabilitation, and generalist case management. Mueser and colleagues (

22) described six models: broker case management, clinical case management, strengths case management, rehabilitation case management, assertive community treatment, and intensive case management. They pointed out that the models could be grouped into three broad types, although they acknowledged that "the differences between models within each of these broad types of community care can be difficult to establish."

Rather than describing discrete models, Thornicroft (

1) proposed 12 dimensions that could be used to distinguish case management programs. Thus there appears to be little consensus about the best way to specify models of case management.

A commonly articulated conceptualization of case management distinguishes between assertive community treatment and other forms of case management (

7,

8,

17,

18,

19,

21). For example, Marshall and colleagues (

18,

19) have distinguished assertive community treatment from other models of case management on several dimensions, including lower caseloads, team rather than individual case management, an emphasis on outreach, and an orientation to the teams' providing as many services as possible rather than referring clients to other providers. Arguably, assertive community treatment has some elements in common with other forms of case management as well as some unique features. It is therefore reasonable to investigate both the common and the specific effects on outcomes of these different approaches.

Most previous reviews have been narrative accounts that compare the number of studies finding positive results to those finding negative results in order to determine overall trends. However, as Glass and associates (

24) and others have shown, such methods can lead to inaccurate conclusions. There have been four attempts to combine results quantitatively using meta-analytic methods (

13,

18,

19,

21). Bond and colleagues (

13) examined studies of the implementation at nine sites of the Thresholds Bridge program, which is based on the assertive community treatment approach. Gorey and associates (

21) used a meta-analytic approach to evaluate the effectiveness of case management more broadly. However, both analyses included controlled studies as well as studies that used a baseline-versus-intervention design. The latter design confounds change resulting from the intervention with change occurring over time resulting from factors not related to the intervention.

The meta-analytic studies of Marshall and colleagues (

18,

19) analyzed assertive community treatment and other models of case management separately. The meta-analysis of the effectiveness of assertive community treatment found that clients in these programs were more likely than clients receiving usual treatment to remain in contact with services and less likely to be hospitalized; assertive community treatment clients spent less time in the hospital and had better outcomes on housing status, employment, and satisfaction with services (

19). For other models of case management, Marshall and colleagues were able to reach conclusions for only two domains of outcome; they found that a greater proportion of case management clients were hospitalized (reported also as an increase in total admissions among case management clients) and that case management clients were less likely to drop out of mental health services (

18).

To compare the effectiveness of assertive community treatment directly with generic or clinical case management, Marshall and colleagues (

19) examined only those studies in which clients were randomly assigned to one model or another. However, because only six trials met this criterion, firm conclusions could not be drawn.

We decided to replicate the approach of Marshall and colleagues, but we broadened the inclusion criteria so that more studies and outcome domains could be included. One approach to comparing the effectiveness of assertive community treatment with clinical case management is to examine studies that directly compare outcomes for these two models—the within-study approach. However, Marshall and colleagues found only six such studies. An alternative is to examine the relative strength of the effectiveness of each model compared with usual treatment. This approach entails examining whether, for example, assertive community treatment is more effective than usual treatment on some domain of outcome than is clinical case management. Although this method is less strictly controlled, more studies can be included.

We also decided to include studies using measures for which reliability and validity data had not been previously published, rather than limit the analysis to studies using only established measures. Although the inclusion of some unreliable measures will attenuate the estimated average effect size, it may nonetheless increase the power of the analysis to determine whether there is any effect at all. The combination of these methods allowed us to conduct a broader examination of the effectiveness of case management as called for by Parker (

25) and extended the range of outcomes subjected to meta-analysis.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effectiveness of case management compared with standard community care without case management. We conducted a meta-analysis of the results of controlled studies of the effectiveness of case management. A second aim of the study was to compare outcomes of assertive community treatment and clinical case management.

Methods

Literature search

The analysis included studies of outcomes of case management in mental health services published between 1980 and 1998 in refereed journals. Studies were included if their focus was on the treatment of adults with serious mental illness such as psychosis, affective disorders, personality disorders, or anxiety disorders. Studies in which subjects had a diagnosis of a substance use disorder were included if subjects also had another diagnosis; however, studies in which subjects' sole or primary diagnosis was a substance use disorder were not included.

To be included in the analysis, studies also had to compare outcomes of a group receiving case management with those of a group receiving standard community care but not case management, or they had to compare outcomes of a group receiving assertive community treatment with those of a group receiving another form of case management. The studies included in the analysis had dependent variables that were measures of client outcome, such as hospitalization, quality of life, satisfaction, and level of community functioning.

The first sampling strategy was to examine studies cited in previous reviews of case management in mental health services (

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22) that met the criteria outlined above. Second, MEDLINE and PsycLIT searches were conducted using the terms case management, care management, care programming, or assertive community treatment and mental health, psychiatric, or psychiatry and evaluation, outcome, comparison, or effect.

The combination of these two methods yielded approximately 180 articles in English-language journals. Some of these articles reported comparisons of clients in two or more types of case management with clients in control groups. The results of other studies were reported in several articles, but they are included here as a single article. For our analysis, each comparison was coded and included as a separate study when possible; however, studies for which different outcomes were reported in more than one article were included only once. Studies comparing assertive community treatment and another model of case management were included and analyzed separately.

Measures

Each study was coded for client characteristics as well as several aspects of the study design, including sample size, study period, number of outcome measures used, attrition rates, and the method of assigning subjects to treatment groups. Each study was categorized by an estimate of research quality using criteria similar to those used by Glass and associates (

24). These categories were random assignment to conditions with attrition less than 20 percent (high rating); random assignment with attrition greater than 20 percent or differing between groups (medium-high rating); well-designed matching studies or analysis for covariance (medium-low rating); and weak or nonexistent matching procedures (low rating).

Standardized measures of outcome were calculated for each of 12 domains. The domains were improvement in symptoms (excluding the Global Assessment of Functioning and Global Assessment scales), which include both symptoms and level of social functioning; number of hospital admissions; length of hospital stay; proportion of clients hospitalized; contacts with mental health services; contacts with other services; dropout rates from mental health services; level of social functioning, measured as quality of life rated by clinicians and clients on the basis of clients' level of social functioning and improvement in their housing situation; clients' satisfaction; family members' satisfaction; family burden of care; and cost of services.

Statistical analysis

Two methods were used to calculate standardized measures for each domain of outcome—the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient (r) and the one-tailed level of significance (p). Although several measures of effect size are in use, we regarded r as being a more well-known and interpretable statistic than other effect size measures. Correlation coefficients can be derived from other statistics such as t values, means and standard deviations, and one-factor F values (

26). The META computer program (

27) was used to calculate r from reported statistics.

When possible, the one-tailed p value was also calculated for each outcome measure independently of whether the actual r could be calculated. One-tailed p values were obtained by halving the reported two-tailed probability if it favored case management and by subtracting the halved two-tailed value from one if it favored the control group. For example, a two-tailed p of .05 in favor of case management was coded as .025, and a two-tailed p of .05 in favor of the control group was coded as .975.

If studies simply reported the result as not significant, p was coded as .5 (

26). When a study reported more than one result in domains that were combined, such as two different symptom measures, the mean p or r was calculated (

26). All r and p values were calculated by the first author, and after all studies had been coded, each r or p value was recalculated and any inconsistencies resolved. For relevant outcome domains, we recorded whether the measure used in the original study had previously been reported in peer-reviewed journals. Missing data were excluded from the analysis.

The weighted mean r for each outcome domain was calculated by converting each r to a standard normal deviate (Fisher's z) and weighting each z by the study's sample size and research quality (

26,

28,

29). The 95 percent confidence interval was calculated for each weighted mean r (

28). As a separate analysis, the combined p value was calculated for each outcome measure by calculating the standard normal deviate for each p reported and weighting by sample size and research quality (

26). To investigate the impact of possible publication bias, we calculated Rosenthal's fail-safe N for each combined p (

26) and calculated the regression asymmetry test for publication bias first suggested by Egger and associates (

30,

31). The fail-safe N is an estimate of the number of studies with nonsignificant results that would have to be added to the sample in order to change the combined p from significant (at .05) to nonsignificant. Egger and associates' asymmetry test is a formal statistical test using relative effect size and sample size from each study to detect whether effect sizes are biased.

Homogeneity analysis techniques devised by Hedges and Olkin (

29) were used to compare the effect sizes between groups. This technique, which is based on effect sizes, determines whether variance within and between groups is significantly greater than would be expected by chance. Q values can be calculated for the heterogeneity that exists within groups (Q

within) and between groups (Q

between). If there is a real difference in outcomes between groups, Q

between will be significant on the basis of the chi square distribution (

29).

To compare outcomes of assertive community treatment and generic or clinical case management, two techniques were used. First, the combined p and weighted mean effect size were calculated for studies that directly compared these programs. Because the number of such studies was small (nine), we also analyzed all studies comparing case management with a control group by calculating Qbetween to compare differences between outcomes of assertive community treatment and clinical case management.

Results

Selection of studies

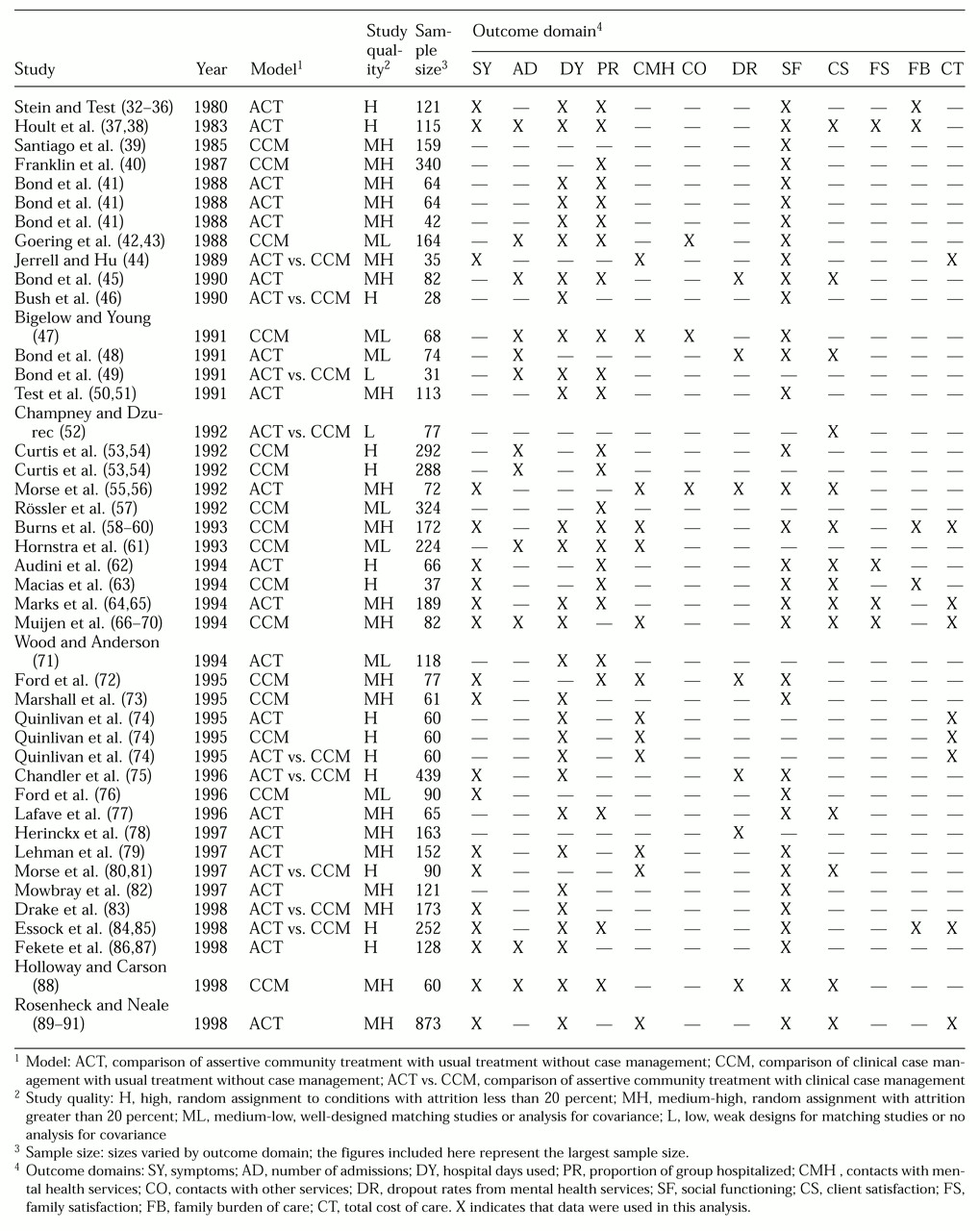

Table 1 lists the 44 studies and identifies the outcome domains included in the meta-analysis (

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84,

85,

86,

87,

88,

89,

90,

91). Thirty-five comparisons of either assertive community treatment or another model of case management with usual treatment were found that met the criteria for inclusion. These comparisons were reported in 50 separate articles (

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

42,

43,

45,

47,

48,

50,

51,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

76,

77,

78,

79,

82,

86,

87,

88,

89,

90,

91). Some articles appear in the table more than once because they report the results of separate comparisons. Nine studies were found that directly compared assertive community treatment with another model of case management. These comparisons were reported in 11 separate articles (

44,

46,

49,

5274,

75,

80,

81,

83,

84,

85), which are shown in

Table 1 as assertive community treatment versus clinical case management.

Six studies that met the inclusion criteria were not included in this analysis. One used criminal justice contacts as the only outcome measure, and this domain was not included in our study (

92). In another study the case management and control groups received services for different amounts of time (

93). In the other studies (

94,

95,

96,

97,

98,

99,

100), neither effect sizes nor p values could be retrieved.

The type of case management was recorded according to the definition used by the authors of the report. Initially we used Solomon's typology (

8) of assertive community treatment, strengths case management, rehabilitation, and generalist case management models to record types of case management. Nineteen studies compared assertive community treatment with usual treatment (

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

41,

45,

48,

50,

51,

55,

56,

62,

64,

65,

71,

74,

77,

78,

79,

82,

86,

87,

89,

90,

91). Sixteen studies compared another model of case management with usual treatment—one with a strengths model (

63), one with a rehabilitation model (

42,

43), one with a generalist model (

40)—and 13 other studies that could not be further classified (

39,

47,

53,

54,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

72,

73,

74,

76,

88).

We refer to these other models as "clinical case management." They all included a single person responsible for conducting needs assessment, developing individual plans, coordinating access to needed services, and monitoring mental state and social functioning. In addition, most emphasized the importance of the case manager's establishing a therapeutic relationship and providing ongoing care rather than acting merely as an administrative service broker. Thus the models described correspond to Kanter's description of clinical case management (

101), although they also seem to share features of the strengths and rehabilitation models described by Mueser and colleagues (

22).

The assertive community treatment programs in the studies we analyzed provided intensive support and many of the case management functions listed above, but they differed in several ways: they operated with teams of two or more that were responsible for each client, they had lower caseloads, and they often—but not always—provided more services from within the program rather than referring clients to other services. In 14 of the 19 assertive community treatment programs (74 percent), case managers had caseloads of ten to 19 clients. In the other five programs (26 percent), case managers had fewer than ten clients.

In nine of the 16 clinical case management programs (56 percent), case managers had caseloads of ten to 19 clients; in the other seven clinical case management programs (44 percent), case managers had caseloads of 20 or more clients. Usual treatment was generally provided via outpatient visits to a community mental health facility.

Client characteristics

A total of 6,365 clients were included in the 35 studies comparing case management with usual treatment. Eighty-three percent (N=5,283) were single, which included the categories of never married, widowed, and divorced. Fifty-six percent of the clients (N=3,564) were male. The mean±SD age was 37±5 years. The mean±SD number of previous psychiatric admissions was 6.6±2).

In the 19 studies that reported DSM axis I diagnoses for all clients, 61.6 percent of clients (N=2,023) were diagnosed as having schizophrenia, 7.8 percent (N=257) had bipolar affective disorder, 9 percent (N=297) had another psychotic disorder, 11.4 percent (N=376) had depression, 2.1 percent (N=69) had neurosis, and 8.1 percent (N=267) had another diagnosis. No statistically significant differences between case management and control groups were found for any of the demographic variables or for diagnosis. However, information about previous admissions was unavailable in 25 of the 35 studies (71 percent) because admissions were reported in a format that did not allow comparisons across studies.

Study characteristics

Of the 35 studies comparing case management with usual treatment, 29 (83 percent) employed control groups to which clients were randomly assigned. The mean±SD length of the study period, which was defined as the length of time during which the two groups received different services until the final measure for comparison was recorded, was 16.5±6.7 months. The mean±SD attrition rate was 15.9±9.3 percent for case management groups and 23.4±10.9 percent for control groups. The median size of the study samples varied considerably across outcome measures, from a maximum of 121 clients for the proportion of the group hospitalized to a minimum of 32 for family satisfaction.

Outcomes

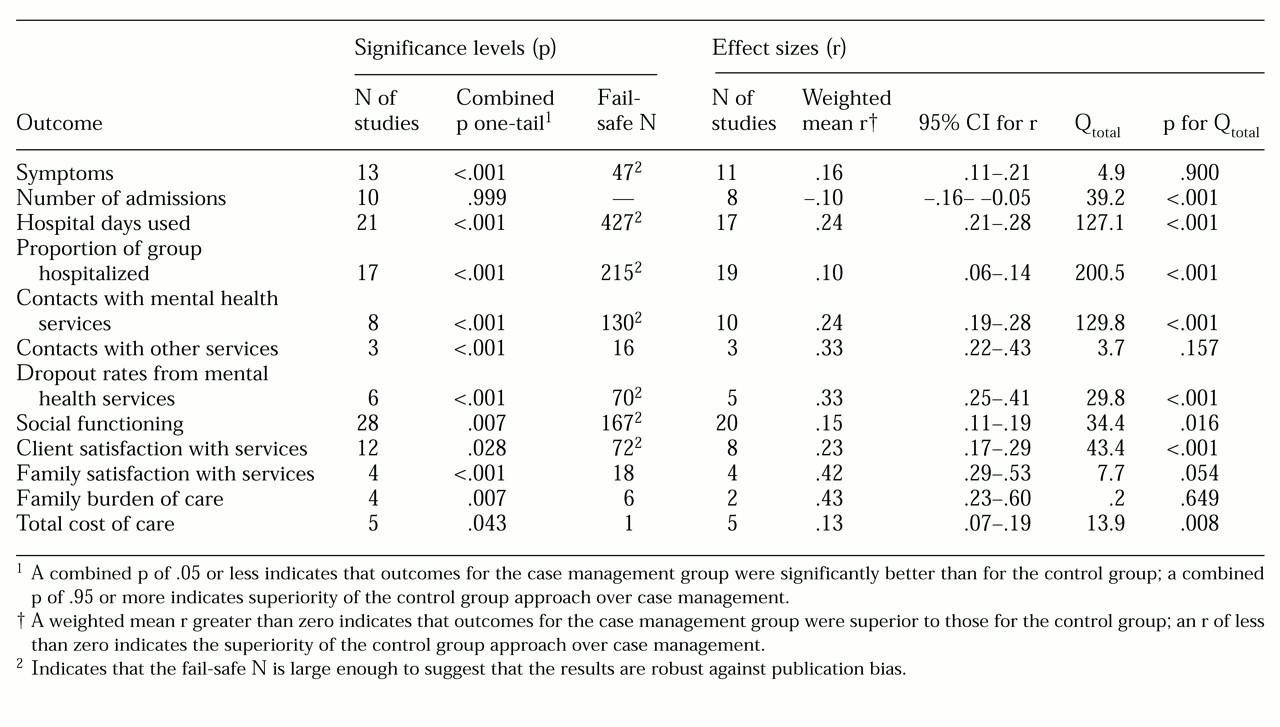

The results of the comparison of case management with usual treatment are presented in

Table 2, which shows each outcome domain by the number of studies contributing p values, the combined one-tailed p, Rosenthal's fail-safe N, the number of studies contributing r values, and the weighted mean r and its associated 95 percent confidence interval. Case management programs were more effective than usual treatment for most types of outcome, measured both by a combined p of .05 or less and by the probability that r is significantly greater than zero at the 95 percent confidence level.

Specifically, compared with usual treatment, case management was associated with greater improvement in symptoms, fewer hospital days used, a smaller proportion of clients hospitalized, more contacts with both mental health and other services, lower dropout rates from mental health services, greater improvements in level of social functioning, greater client and family satisfaction with care, less family burden of care, and lower total cost of care. Clients of case management programs were admitted to the hospital more frequently than clients receiving usual treatment.

Publication bias

Although most of the relationships were highly statistically significant, it is possible that because of publication bias, studies finding nonsignificant results were not published and thus could not be included in this analysis. Rosenthal's fail-safe N is shown in

Table 2. There are no objective criteria by which to judge when the N is large enough to ensure confidence in the validity of the results; however, Rosenthal (

26) suggested that a fail-safe N greater than or equal to five times the number of comparisons plus ten means that the results could be considered "robust." By this criterion, six domains could be considered robust against publication bias on the basis of reported p values: fewer hospital days used, a smaller proportion of clients hospitalized, more contacts with mental health services, lower dropout rates, greater improvement in social functioning, and increased client satisfaction.

Egger's test for publication bias (

30,

31) was calculated for each outcome domain except contacts with other services, family burden of care, and family satisfaction, which had sample sizes too small to plot. Three of the remaining nine domains showed some evidence of publication bias: the proportion of clients hospitalized (p=.015), contacts with mental health services (p=.017), and client satisfaction (p=.05). These results differ slightly from those for the fail-safe N because they are based on effect sizes rather than p values.

Study quality

The Q

total values and associated level of significance are shown in

Table 2. Nine domains had variance greater than that which would be expected by chance. We tested whether the quality of the research design was associated with different outcomes for these measures by collapsing the four categories for research quality into high-quality and low-quality categories and comparing weighted mean r values for these two groups.

Four of these nine measures showed significant differences in outcomes by study quality: number of admissions (Qbetween=14.7, p<.001), days hospitalized (Qbetween=4.6, p=.03), contacts with mental health services (Qbetween=12.2, p<.001), and level of social functioning (Qbetween=4.8, p=.028). However, the weighted mean r values for the high-quality group were almost the same as those calculated for the sample as a whole. For number of admissions, the weighted mean r for the high-quality group was -.14, compared with -.10 for the total sample; for days hospitalized, it was .26, compared with .24; for contacts with mental health services, it was .21, compared with .24; and for level of social functioning, it was .14, compared with .15. Taken together, these figures suggest that including matched-control studies and weighting for study quality increased the power of the analysis while effectively limiting the impact of lower-quality studies on the overall estimates of effect size.

We also examined the impact of using measurement instruments that had or had not been previously described in peer-reviewed journals, because this was one of the criteria used by Marshall and colleagues (

18,

19) to exclude some outcome domains. We compared the weighted mean r value for studies in which previously reported measures were used with those in which the measures used had not been previously reported in peer-reviewed journals. The number of studies using both reported and nonreported measures was sufficient to enable a comparison for only two domains. For both domains, the mean weighted effect sizes were significantly higher for the studies that used previously reported measures than for those in which nonreported measures were used: level of social functioning (r for reported measures, .18; r for nonreported measures, .13; Q

between=4.41, p=.036); and client satisfaction (r for reported measures, .38; r for nonreported measures, .19; Q

between=8.54, p=.003). Assuming that instruments not described in previous reports have lower reliability rates, the findings support our a priori assumption that these measures may tend to underestimate effect sizes.

Assertive community treatmentand clinical case management

We first examined studies that directly compared assertive community treatment programs with clinical case management programs. No differences between programs were found in previous admissions, age, the percentage of clients with psychosis, the proportion of males and females, or the percentage of single clients. All but two domains had fewer than four studies contributing effect sizes—too few to allow any firm conclusions to be drawn. Assertive community treatment was superior to clinical case management in improving social functioning (five studies, r=.18) and marginally superior in reducing the total number of days hospitalized (five studies, r=.08), although the small number of studies limit confidence in these findings.

To investigate this issue further, we compared outcomes for controlled assertive community treatment studies with outcomes for controlled studies of clinical case management. Clients in the assertive community treatment studies had more previous admissions than those in the clinical case management studies (7.4 compared with 4.7 admissions; t=2.35, df=8, p=.047); however, data were available from only nine studies. No significant differences were found in age, percentage of clients with psychosis, proportion of males and females, or percentage of single clients.

The Q

total scores and the associated levels of significance shown in

Table 2 indicate that there was no statistically significant difference in outcomes for improvement in symptoms, contacts with other services, and family burden of care. This finding suggests that on these measures, case management was effective but that assertive community treatment and clinical case management were no different; however, only two studies assessed family burden of care.

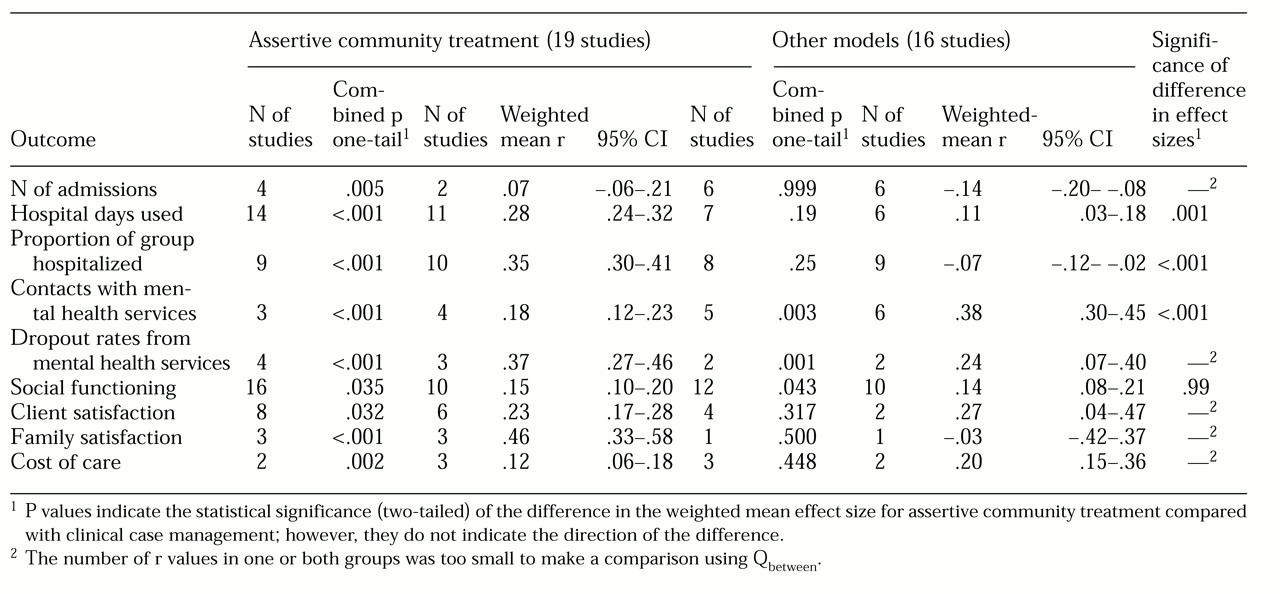

The remaining nine domains were analyzed further by comparing outcome effect sizes for assertive community treatment with those for clinical case management. Results are shown in

Table 3. For the number of admissions, effect sizes could be calculated only for two studies in the assertive community treatment group, making comparison using Q

between impossible. However, enough studies reported p values for this domain to show that assertive community treatment was effective in reducing the number of admissions, whereas clients in clinical case management had a larger number of admissions (the combined p being significant in the opposite direction).

As

Table 3 shows, for days spent in the hospital, the assertive community treatment studies showed a significant positive effect according to both combined p and weighted mean r; however, clinical case management showed a significant positive effect for weighted mean r only. The weighted mean effect size for days in the hospital was significantly greater for assertive community treatment than for clinical case management.

For the proportion of clients hospitalized, the assertive community treatment studies showed a significant positive effect according to both combined p and weighted mean r, suggesting that a smaller proportion of clients in assertive community treatment than clients in usual treatment were admitted to a hospital. For the clinical case management studies, the weighted mean r and combined p values were not significant, suggesting that clinical case management did not differ from usual treatment. Assertive community treatment was significantly better than clinical case management in reducing the proportion of clients hospitalized.

As shown in

Table 3, a higher frequency of contact with mental health services was found for clients in both assertive community treatment and clinical case management, according to both weighted mean r and combined p; however, the number of contacts was significantly greater for clients in clinical case management programs than for clients in assertive community treatment programs.

On the basis of weighted mean effect sizes, clients in both assertive community treatment and clinical case management had a higher level of social functioning, lower dropout rates from mental health services, and higher satisfaction; the total cost of care was lower in both types of program. No differences were found between the two types of program in clients' social functioning; however, for dropout rate, satisfaction, cost of care, and family satisfaction with care, the number of studies was too small to allow comparison using Qbetween.

Discussion

The findings of this study considerably extend our knowledge about the effectiveness of assertive community treatment and clinical case management and the differences between them. We found that clinical case management is generally effective in improving outcomes from mental health services, as measured by clients' level of social functioning, symptoms, client and family satisfaction, and family burden of care. These results directly contradict the claim of Marshall and colleagues (

18) that there is little evidence that case management improves clients' mental state, social functioning, or quality of life.

We have also elaborated on Marshall's finding that clinical case management increases the proportion of clients hospitalized, by showing that it increases the total number of admissions but that it decreases the total length of stay in the hospital. This finding means that although clinical case management led to more admissions than usual treatment, these admissions were shorter, which reduced the total number of hospital days. These results suggest that the overall impact of clinical case management on hospitalization was positive, again contradicting Marshall's rather pessimistic conclusions (

18).

We have replicated the findings of previous reviews in showing that assertive community treatment programs are superior to clinical case management in reducing hospitalization, both in terms of the proportion of clients admitted and the total length of stay. However, for the first time, we have shown that these two approaches appear to be equally effective in improving symptoms, improving social functioning, and increasing clients' satisfaction with services. The total cost of care was reduced in both types of case management, but different methods of calculating costs limit confidence in this finding. The results should be interpreted with caution because assertive community treatment programs may deal with a different client group than clinical case management programs. For example, clients in assertive community treatment in the studies we analyzed had a greater number of previous admissions before program entry than clients receiving clinical case management.

It is useful to consider the effect of different aspects of case management on outcomes. Assertive community treatment programs often include a specific goal to avoid or at least minimize hospitalization, and staff on these teams may be able to make decisions about admissions, while staff on other programs do not. This decision-making ability may have a major influence on hospitalization as a measure of outcome, independent of other considerations for admission such as mental state or level of social functioning.

A notable feature of the data was that average outcomes for clients in different programs varied widely. One reason for the diversity of outcomes may be the tension between monitoring and support of people with a mental illness. A greater emphasis on monitoring may result in more hospital admissions and less client satisfaction, because clients may perceive that case managers are intrusive and controlling. That clients in clinical case management programs had more admissions than those in usual treatment could be evidence of greater monitoring. However, the shorter total length of stay, together with the overall improvement in symptoms and social functioning, suggests instead that admissions may be more timely and may thus prevent the need for longer stays. Nevertheless, reconciling the monitoring and support functions remains an important dimension of case management programs.

Another reason for differences in outcomes may have been some variation in the difference between the case management programs and usual treatment. For example, some of the usual-treatment programs may have incorporated aspects of case management into their standard practices and procedures.

The main difference between this study and the study of Marshall and associates (

18) is that we analyzed a greater number of studies by including matched control groups as well as randomly assigned control groups, by including outcome data regardless of whether the measure had previously been reported in a peer-reviewed journal, and by not excluding studies that used parametric methods with skewed data. It is worth considering the effects of these differences. We have demonstrated that the inclusion of matched-control studies increased the power of the analysis and enabled conclusions to be drawn for a broader range of outcomes than previously considered; this was accomplished without lower-quality studies biasing the results. We also demonstrated that studies using unpublished outcome measures tended to underestimate effect sizes but nonetheless provided evidence in favor of the effectiveness of case management.

Thus our results may in fact underestimate the effectiveness of case management. The analysis of skewed data with parametric statistics could be of concern, but simulation studies, such as those described by Sawilowsky and Blair (

102), indicate that tests are robust to skewness as long as the sample sizes are reasonably large (larger than 30). That was the case for the studies included in this analysis.

Some skepticism has been expressed about the technique of meta-analysis (

103). For example, some meta-analyses may not take into account the fact that studies finding nonsignificant results tend to be published less often—the "file drawer problem" (

104,

105). We found that fewer hospital days, more contacts with services, greater client satisfaction, and improved social functioning could be considered to be robust against the file drawer criticism.

An added strength of this meta-analysis over individual studies—even those of the highest quality—is that it includes results from a wide range of services, which allows us to be more confident that our findings can be generalized to the mental health service system as a whole. In comparison, findings from individual studies may have limited generalizability because of the specific nature of the service under examination. Another limitation of meta-analyses is that they rely on the data supplied by original studies, which may not provide enough detail about some areas. For example, the descriptions of case management programs in the studies we analyzed varied from several pages of detail to only a sentence or two.

Although the effects of case management appear to be small to medium according to the criteria advocated by Cohen (

106), this finding is consistent with results of studies of many other new social programs or treatments. Citing the results of two analyses—one of 24 meta-analyses (

107) and another of 36 meta-analyses (

108)—Cook and associates (

109) concluded that "one strong finding from various meta-analyses is that most new treatments have, at best, small to moderate effects." Similarly, a meta-analysis of the effectiveness of psychotherapy (not specifically for serious mental illness) found an effect size equivalent to r=.3 (

110), which is about the midpoint of the range of effects found for case management. These findings therefore suggest that the effect of case management should neither be overstated nor dismissed.

Three important issues remain to be further explored. First, a limitation of this study was some uncertainty about the extent to which the programs described in the reports analyzed fit the definitions of assertive community treatment and clinical case management provided in the literature. The broad service context in which case management programs are based and the manner in which such programs are implemented vary considerably (

111,

112), which may be additional reasons for the heterogeneity of outcomes found in this study. This issue requires greater attention in evaluation studies, and the more recent phenomenon of measuring the adherence of programs to model specifications is to be welcomed (

112).

Evidence from one study (

112) suggests that closer adherence to the ideal assertive community treatment model in implementation of these programs results in better outcomes, although the only outcome considered in that study was hospitalization, and no control groups were used. We believe a fruitful direction for future research would be to measure case management programs on the 12 dimensions proposed by Thornicroft (

1) or some adaptation of them and then examine the impact of each of these dimensions on outcomes.

Second, the effectiveness of case management may be related to other factors that may play a mediating role, such as the availability of other community resources, the client's relationship to the treating psychiatrist, staff availability, adequacy of funding for services, and so on. These factors may operate independently of adherence to an idealized assertive community treatment model or to other models and need to be investigated separately.

Third, we cannot necessarily assume that case management is equally effective for all clients; some clients may benefit and others may not. For example, some of the studies included in this meta-analysis targeted people who had co-occurring substance use problems or who were homeless. We did not explore the relative effectiveness of case management for these groups compared with other groups of clients or the impact of different models. However, these questions are obviously important, as are the issues of consumer choice of case manager and client participation in needs assessment and planning. These factors need to be explored in future research.

Conclusions

Case management brings about small to moderate improvements in the effectiveness of mental health services. Assertive community treatment has demonstrable advantages over clinical case management in reducing hospitalization. The two approaches have similar effects in improving clinical symptoms, client and family satisfaction with services, and the client's level of social functioning.

The results of our meta-analysis reinforce the view that assertive community treatment should be targeted to clients who are at the greatest risk of hospitalization and that both assertive community treatment and high-quality clinical case management should be a feature of mental health programs (

84). Our findings imply that the widespread introduction of case management in mental health services has been a positive initiative.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mary Ann Test, Ph.D., for her suggestions for the study design and Steven Klimidis, Ph.D., and Dean McKenzie, B.A., for comments on an earlier draft of this paper. They also acknowledge the support of the Victorian transcultural psychiatry unit. This work was partly funded by a grant from the mental health branch of the Victorian Government Department of Human Services.