On December 1, 1991, the U.S. Congress implemented the Patient Self-Determination Act. This law requires that all health care facilities that receive government reimbursement inform their patients about advance directives and their right to have one on admission. Each patient also must be informed of the institution's written policies on the implementation of the patient's rights, and notification of the patient must be documented in the chart. Finally, the patient must be informed that the facility will not discriminate in the quality of health care on the basis of the patient's advance directive status. However, only 9 to 32 percent of adult patients have an advance directive (

1). Seventy-five percent of physicians are unaware that their patients have an advance directive (

2).

Many physicians fear that a discussion about do-not-resuscitate orders will arouse the patient's fears about death, and in the case of patients with affective disorders, they fear that discussion will increase the patient's anxiety or hopelessness (

3). Physicians also worry that the patient might feel that the provider has given up on healing the patient (

4). Many question whether patients can predict how they would feel or wish to act in a given situation. Also, many patients have a weak knowledge of advance directives and are confused by the terminology (

5).

Many psychiatrists have paid little attention to the Patient Self-Determination Act (

3), perhaps because the discussion of advance directives has focused on the general withholding of life-sustaining care rather than on how advance directives are relevant to psychiatric care (

6). However, depression may affect cognitive ability as well as thoughts about death (

7). Although depression can impair a patient's thinking, it may not change the patient's decisions about treatment. Cotton's 1993 study (

8) showed that geriatric patients' treatment choices were not affected by depression. Nevertheless, patients with severe emotional distress who require hospitalization are encouraged to defer major life decisions until their mental status improves (

3).

Many psychiatrists are aware of and question the line between the legitimate removal of life-sustaining care and suicide (

6). As Lee (

7) has noted, "Suicide prevention is based on the belief that the most hopeless situation might improve if one is prevented from acting in a moment of despair." What about decisions about life-sustaining treatment? In 1986 the California Supreme Court stated that the refusal of life-sustaining medical treatment is not suicide but rather an exercise of the right of privacy (

7).

The study reported here was designed to evaluate the relationship between advance directive status and degree of suicidal ideation along with other demographic variables among geriatric patients suffering from affective disorders.

Methods

This retrospective study reviewed the advance directives of all patients age 60 and older admitted to a geriatric psychiatry unit at a university hospital between March 1996 and May 1998 with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder. Severity of depression was not assessed. Of 192 patient charts examined, all were included in the study except one that did not include information about advance directive status. All patients were from the northeastern United States.

Data recorded from each patient's chart included age, diagnosis, length of stay, marital status, gender, religion, psychiatric history, family psychiatric history, Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score, and suicidal ideation. The advance directive status was divided into two categories —whether cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was to be carried out or not carried out. Patient age was also divided into two categories—patients under 70 years old and those 70 or older—to determine differences between the "young old" and the "old old." Length of stay was also divided into two categories—a median stay of less than 12 days or of 12 days or longer. Suicidal ideation was recorded as either present or absent.

Data were analyzed using the computer program SPSS. The association between variables was evaluated using the exact method of Pearson's chi square. The significance level was set at p<.05.

Results

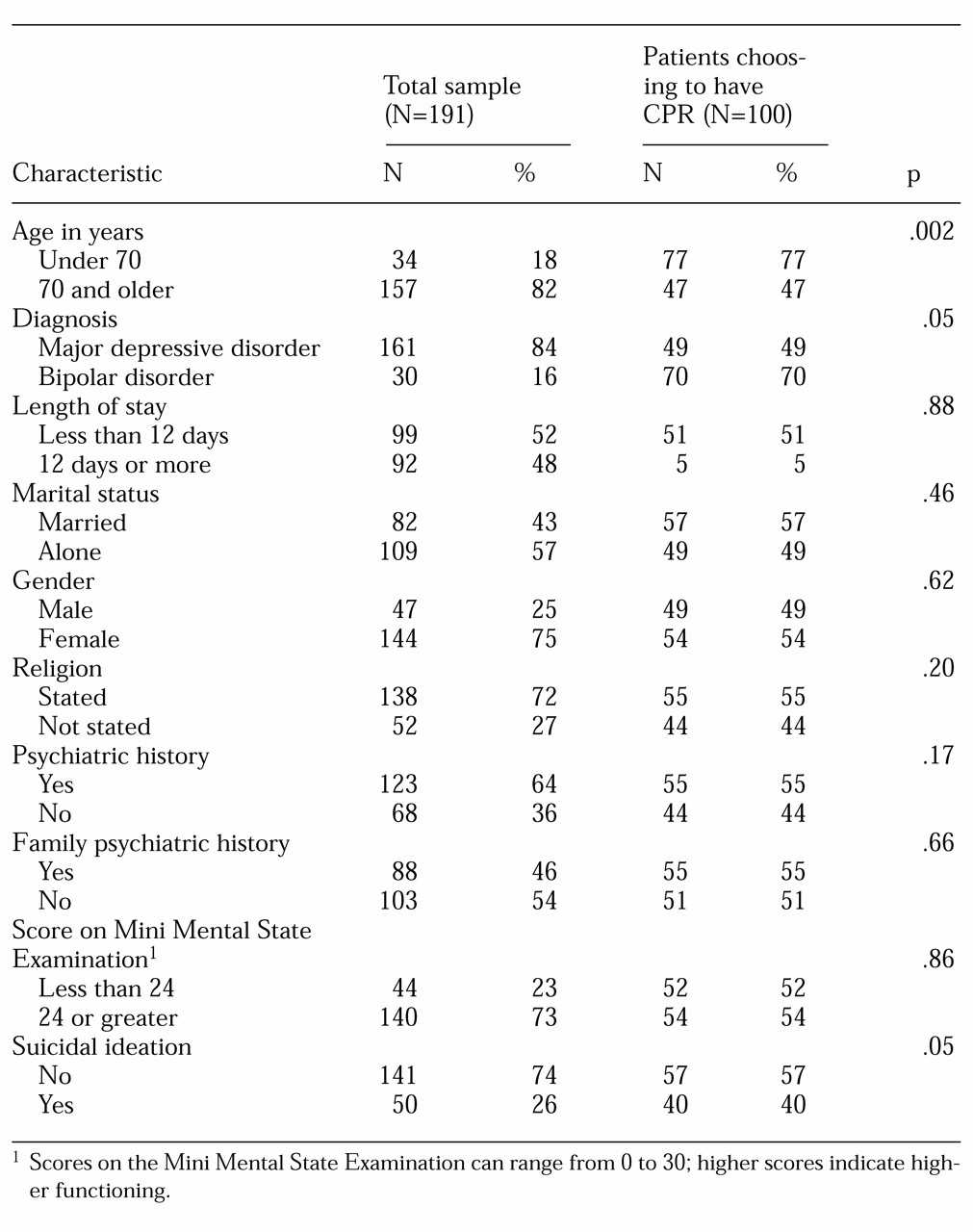

Overall, 91 patients (48 percent) wanted no CPR, 22 (12 percent) wanted CPR only, and 78 (41 percent) wanted all therapy performed in a life-threatening situation. As

Table 1 shows, elderly patients who had suicidal ideation were significantly less likely to ask for CPR than those who did not have suicidal ideation. Forty percent of patients with suicidal ideation asked for CPR if necessary, compared with 56.7 percent of those without suicidal ideation (χ

2=4.15, df=1, p<.05).

Diagnosis was also significantly related to advance directive status. Seventy percent of those who were diagnosed as having bipolar disorder chose to have CPR if needed, compared with 49.1 percent of those diagnosed with major depressive disorder (χ2=4.44, df=1, p<.05). Diagnosis did not appear to be confounded with suicidal ideation—131 patients with major depressive disorder (81.6 percent) had no suicidal ideation, compared with 28 patients with bipolar disorder (92 percent).

Age was found to be significantly associated with advance directive status. Among geriatric patients under age 70, 76.5 percent chose CPR compared with 47.1 percent of patients 70 years of age or older (χ2=9.64, df=1, p=.002). Age and diagnosis appeared to be confounded; 22 patients under age 70 (64.7 percent) were diagnosed as having major depressive disorder, compared with 139 of those 70 years of age or older (88.5 percent) (χ2= 11.99, df=1, p=.001). The relationships between age and suicidal ideation and diagnosis and suicidal ideation were not significant.

To adjust for possible confounding among age, diagnosis, and suicidal ideation, we employed logistic regression followed by the likelihood ratio test. Age made the strongest contribution to the variation in advance directive status (χ2=6.99, df=1, p=.004), and suicidal ideation made less of a contribution (χ2=2.95, df=1, p=.08). Diagnosis did not make a significant contribution.

Discussion

Many authors have expressed concern that depressed patients may not be able to make rational decisions about long-term treatment (

3,

6,

7). However, not all medical professionals feel that depression adversely affects a patient's ability to make decisions about advance directives (

8). Few data are available to help guide clinicians in this matter. In this study, elderly patients who had suicidal ideation were significantly less likely to ask for CPR as part of their advance directive than those who did not have suicidal ideation. This finding suggests that having suicidal ideation affects an older person's choice of advance directives. Thus a patient's psychopathology may indeed affect treatment decisions.

Age also was found to be associated with the choice of advance directive. Patients under age 70 in the study were much more likely than those 70 years of age or older to request CPR as part of their advance directive.

More data are needed to determine whether all elderly patients with affective illness should be asked about their advance directives. In our setting, we continue to ask all geriatric psychiatric inpatients about their advance directives and respect their wishes.