The health hazards of tobacco smoking are widely known—both acute symptoms, such as shortness of breath, and the elevated risk of developing serious and chronic conditions such as cancer, heart disease, and emphysema. People who have been diagnosed with serious mental illnesses, and especially those with schizophrenia, are much more likely to smoke than the general adult population (70 percent versus 30 percent) (

1,

2,

3). Although many different explanations have been proposed for this high prevalence, a matrix of causes is most likely, including neurological, psychological, behavioral, and environmental factors (

4,

5,

6).

Smoking cessation is gradually receiving increased attention among mental health service providers. The low rates of cessation success found for interventions in mental health facilities—10 to 20 percent, usually defined by six or 12 months' abstinence (

6,

7)—largely reflect the difficulty of quitting tobacco smoking; relapse and failure to quit are common in the general population as well (

7). In addition, factors specific to smoking among people with serious mental illnesses likely add to this difficulty (

4,

8). Understanding and addressing these factors—such as health beliefs, interactions between psychiatric medications and nicotine, and ways smoking is inadvertently reinforced within mental health programs—would likely enable programs to adopt or adapt cessation programs to more closely fit their clients' needs (

9,

10) and perhaps increase success rates.

Persons attending mental health programs have a high prevalence of tobacco use but little access to help with stopping smoking. This study was designed as a first step toward understanding what might be needed to create maximally effective intervention and prevention programs in psychosocial rehabilitation programs. We conducted a pilot study of five focus groups made up of clients from two such local programs with the goal of better understanding smoking and quitting from the perspective of this population.

We elected to use the focus group technique because it would enable us to learn about a wide range of influential factors from consumers themselves through an open data-gathering process; to use a group format so that participants could build on one another's ideas, thereby increasing the range of ideas reported to us; and to involve mental health consumers in shaping research that could affect therapeutic programs.

The discussion topics were based on previous literature and experience and included reasons for smoking or for quitting; pros and cons of smoking and of quitting or of being a nonsmoker; health beliefs about tobacco smoking; and experiences of and beliefs about the relationship between smoking and mental illness or psychiatric symptoms.

Methods

We formed five focus groups during the summer of 1999, each consisting of six to ten persons, in two different psychosocial rehabilitation programs, one urban and one suburban. A total of 40 people participated: 28 men and 12 women. Age, race, and other demographic characteristics were not recorded because individual-level data and subgroup comparisons were not part of our study. We did note, however, that participants ranged in age from their twenties to their sixties and included African Americans and Caucasians in roughly equal numbers. Many participants identified themselves as having a diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder; a few mentioned major depression or anxiety disorders, and some did not volunteer any information about their diagnosis.

Two groups were made up of people who currently smoked, two of people who currently did not smoke, and one of smokers who did not wish to quit. This last group was added because program staff and researchers agreed that it is an important subgroup in these programs.

At both programs, staff posted sign-up sheets and also individually invited clients they knew had a particular interest in the topic. Our inclusion criteria were simply that participants had to be clients of the program, willing to take part, and able to give informed consent. In addition, they had to identify themselves as best suited for one of the two or three groups being held at their program.

Each focus group was held at the program site. Once everyone was assembled, consent forms were distributed and read aloud, and the study's purpose was explained. In each group, one researcher guided discussion while a second operated the tape recorder, took thematic notes, and acted as a secondary facilitator. Sessions lasted 60 to 70 minutes. Participants were offered refreshments, and at the end of the session each was compensated $5.

We used the same outline of topical questions to guide the discussion in each group. Within this outline, however, we allowed great flexibility, as our purpose was to hear about the issues most important to the participants. The eight primary topics in the outline were reasons to quit and to maintain abstinence and benefits of quitting; reasons for starting or for never starting; strategies for quitting and maintaining abstinence; challenges or obstacles to quitting and maintaining abstinence; perceived benefits of smoking; relationships between smokers and nonsmokers; program policies and practices regarding smoking; and suggestions for programs to better support quitting and maintaining abstinence.

After each group, the audiotape was transcribed, and the transcript was checked against the tape. During transcription and correction, personal names and identifying details were removed or replaced by pseudonyms. The transcripts were then subjected to thematic analysis, in which a pair of the researchers read each transcript independently and noted important potential answers to the guiding global question, "What are the important issues regarding smoking or not smoking for these participants?"

The pair then compared notations for each transcript and resolved differences through discussion until they reached a consensus coding for each group's transcript. The codes for the five group transcripts were then compared and discussed until the researchers agreed on an overall, comprehensive outline of issue categories across all groups. The five transcripts were then recoded using this final consensus outline. In addition, as we proceeded, similarities and differences were noted, along with unusual, common, and emphasized issues. In all stages of analysis we focused on capturing a wide range of ideas and experiences rather than converging on a few.

Results

The five main issue categories of the final coding outline were reasons for smoking, reasons for not smoking, views on health concerns, perceived social costs and benefits of smoking, and strategies for quitting and maintaining abstinence. Each is discussed briefly below.

Reasons for smoking

In all groups, views about smoking reflected in participants' responses were similar to those of the general public, though some issues and emphases were specific to having a mental illness or attending a psychosocial rehabilitation program. On why they smoke—or used to, as only a few had never been smokers—participants spoke of having started as teens and now finding the addiction hard to break, or of now enjoying tobacco's effects. They emphasized the positive antidepressive, antianxiety, calming, and cognitive-focusing effects of tobacco.

The line between tobacco's lessening the effects of daily stress and its helping with psychiatric symptoms was blurry in many instances, although some participants made explicit connections. For example, one person said, "If you're going through a rough time, [mental] illness-wise … and you're getting an enormous amount of activity in your brain, and you just want to take a break, take five, you have a cigarette, and … it helps to focus you, calms your thinking."

In addition, two participants reported that smoking lessens psychiatric symptoms that are not helped by their prescribed medications, and several mentioned tobacco as reducing side effects of psychotropic medications.

Many participants said that they smoke out of boredom. "Just to have something else, something different to do" was a common response. When queried further, they described having a great deal of "empty" time in which other options are unavailable, literally or cognitively.

Similarly, smoking as "one of the few pleasures I have" emerged as a theme. Although this view was often expressed in the first person, participants also described family members, program counselors, and others telling them the same thing. One person recalled, "Other people told me, 'Enjoy your cigarettes, it's the only thing you have.… You don't really have that much in life, you got mental illness.… You don't really have that much in life like normal people have. So, go ahead—at least don't worry about your smoking, at least enjoy your cigarettes.' So, that's the attitude sometimes other people give me about talking about it.… I think it's a good statement. [Others agree.] It's true in a way. I mean, I'm sick, you know, I've had mental illness for 30-something years."

Reasons for not smoking

When asked about reasons to quit smoking or never to smoke, most participants said that cigarette smoking is unhealthy, and they had a general understanding that it can lead to heart and lung problems and to cancer. Some showed detailed health knowledge, while others voiced only vague awareness.

All groups described two different classes of health concerns as motivating them to quit or to wish they could quit: immediate troubling symptoms they or other people had experienced, such as cough, throat irritation, chest pain, and wheezing, and the increased risk of serious health problems in the future, such as developing heart disease, cancer, or emphysema. Having seen a family member or other significant person struggle with or die from smoking-related effects was a particularly powerful reason for a number of people. In addition, some participants were concerned that smoking can exacerbate existing physical and mental health problems.

Views on health concerns

Although all participants mentioned the same health concerns, we noted important differences in the ways smokers, nonsmokers, and smokers not interested in quitting discussed them. These differences seemed to reflect characteristic ways of cognitively dealing with the conflict between the perceived benefits and costs of smoking.

People uninterested in quitting were least likely to spontaneously mention smoking's health effects, and they discussed them in less detail when asked. Some spoke frankly of deliberately not thinking about health ramifications. One participant said, "I just smoke one day at a time and try to not get worried about it." They also described ways of mentally minimizing their perceived risks: "My mom and dad smoked for a long time, and neither one got cancer or anything like that."

A few, however, described accepting the hazards. One said, "In my case, I'm a chronic smoker, so what I got to do—this is a hard thing to do for me—I got to say to myself, 'Alright, I'm going to smoke the rest of my life, but one thing I got to remember is if I do have to die with cancer, then I have to accept it.' That's how severe the addiction is—knowing that if I do, if I really do, in the future end up dying with cancer, then I have to go through it and accept it."

In contrast, nonsmokers frequently and spontaneously cited health concerns as an important reason why they do not smoke, whether they ever did or not. They also emphasized health concerns as validating the wisdom of their quitting, even though some still craved tobacco.

Smokers who voiced some desire to quit were the most equivocal, mentioning health problems but also downplaying them, and articulating conflict between health knowledge and a desire to smoke. Saying they were concerned about the health risks of smoking, or "I know I should quit," but in the same breath explaining why they could not was a common combination. Some said they had convinced themselves that they could beat the odds of illness, and some expressed resignation that their addiction was just too strong for quitting to be possible. They also repeatedly pointed to motivation as an obstacle, emphasizing that people are much less likely to take in antismoking information or to use cessation tools effectively if they are not "ready" to quit.

Social costs and benefits

Although health issues were most prominent, all five focus groups also readily talked about the social meanings of smoking and of abstaining. As one might expect, participants cited recognition from others, enhanced physical functioning, money saved, and the avoidance of smelling smoky as social benefits of quitting. At the same time, quitting was also associated with forgoing the positive effects tobacco has on anxiety, cognition, and depressed mood, which in turn would negatively affect well-being and social interactions.

Participants also noted that in a psychosocial rehabilitation program —where most clients smoke—not smoking sets one apart. As smoking takes places at designated times and places in these programs and therefore involves smokers congregating, not smoking can exclude a person from these social interactions. Some felt left out, and others described the temptation to light up while sitting with their smoking friends. At the same time, most were glad that smoking restrictions had lessened temptation.

Smokers also described social benefits and costs. The interaction of sharing cigarettes or smoking together was mentioned as a benefit, and some participants were unhappy with the growing restrictions and stigma associated with smoking. Smokers also expressed a strong reluctance to expose nonsmokers to secondhand smoke, both out of concern for others' health and because they had seen it annoy people. Some also described smoking as limiting their social contacts with nonsmokers.

The focus group discussions often carried an undercurrent of weighing pros and cons, especially for smokers with some desire to quit. Discussions about cost provided an especially clear example of this tendency. Nonsmokers and former smokers cited cost savings as an important benefit of not smoking. Current smokers complained emphatically about cigarette prices and recent tax increases.

Their complaints were perhaps even more acute than those of nonclient populations since people attending psychosocial rehabilitation programs usually have little discretionary income. Some said price increases have led them to smoke less, roll their own cigarettes, or switch to generic brands. A few mentioned giving up other expenses, smoking nontobacco substances such as tea, or panhandling to afford cigarettes. Although several cited a hypothetical price that would make them quit entirely, many claimed that there was no such price—that although cost was a serious burden, cost alone would never be enough to make them quit.

Strategies for quitting and maintaining abstinence

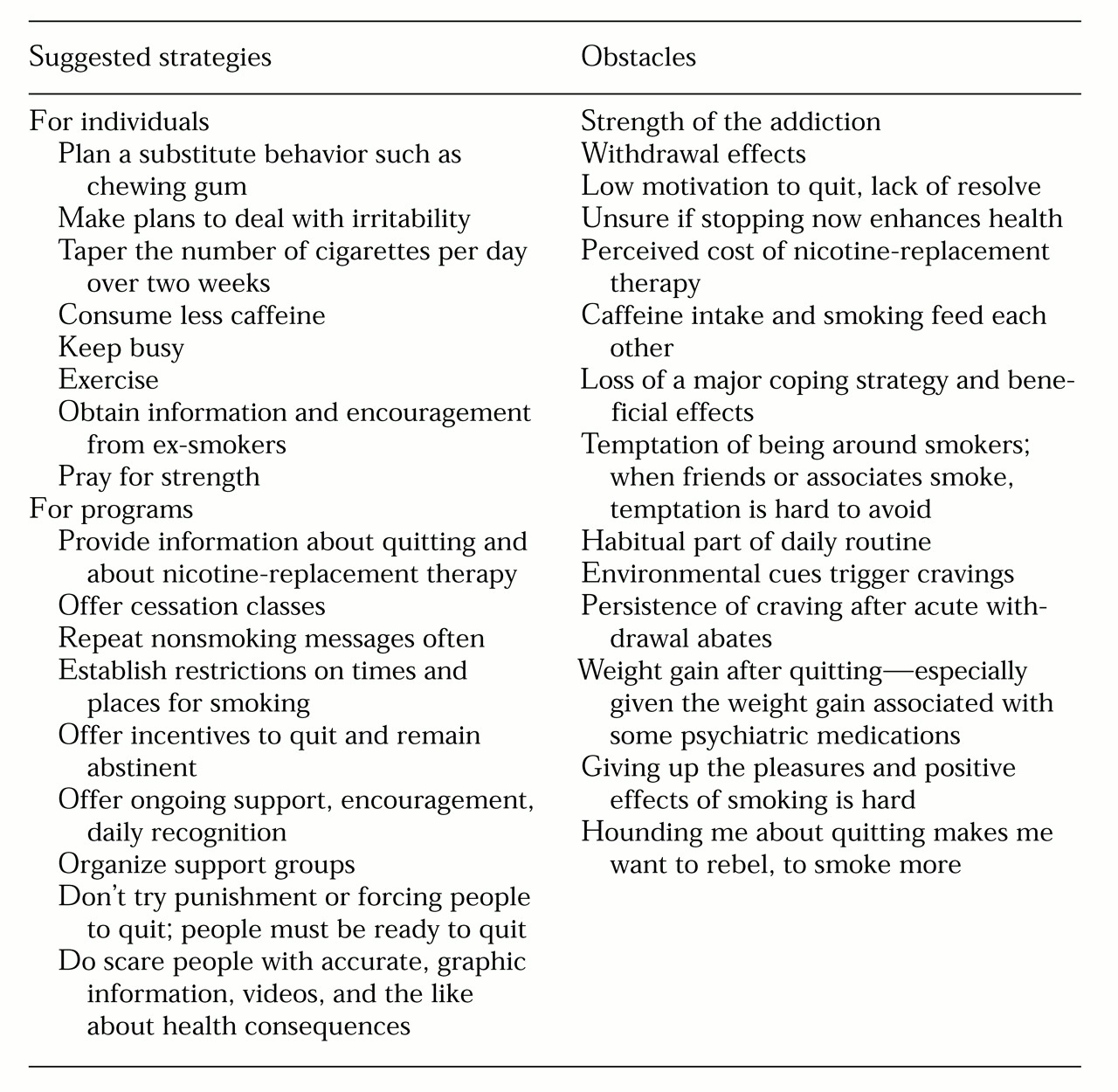

We asked smokers and nonsmokers about strategies they have used successfully or would like to see their program use to help people quit smoking. Their answers emphasized the combined importance of motivation, information, and sustained support (see

Table 1). In addition, in each group pharmacologic means of minimizing withdrawal symptoms such as nicotine patches or gum were mentioned prominently—perhaps because they are the primary methods offered in their programs. There was some confusion about the cost of these methods and their relative effectiveness, and most participants wanted additional information.

Discussion

Throughout the focus group sessions, participants described weighing and struggling with the various costs and benefits of smoking and abstaining, in much the same way that any group of smokers or former smokers might (

11). These conflicts and the fluctuating levels of motivation to quit are consistent with reports in the current literature on tobacco addiction and stages of behavioral change among the general population (

12), and they highlight important issues in designing smoking cessation interventions and support. The fact that some participants had successfully quit contradicts the widely held assumption that addressing smoking cessation in psychiatric populations is impractical. The variety of attitudes about smoking cessation and plans to quit among participants highlights the fact that motivation and current mind-set are critical factors to be taken into account in any smoking cessation efforts.

Although the findings of this pilot study must be considered tentative because of its small and nonrepresentative sample, the participants' emphasis on the emotional and stress-regulation benefits of tobacco is important for several reasons. Many smokers in the general population cite the regulation of affect that use of tobacco provides. However, people in psychosocial rehabilitation programs may experience more difficulties with alertness, anxiety, and depression than the general population because of psychiatric symptoms, medication side effects, or elevated life stresses. Some may have few other resources for coping with stress and negative affect and may rely considerably on the habit and calming effects of smoking.

Furthermore, biochemical research suggests that people with some mental illnesses may have vulnerabilities to addiction and that nicotine may have symptom-abating effects on the brains of some people with schizophrenia (

4,

13,

14). Finally, because of their involvement with mental health issues and services, persons attending mental health programs may be more attuned to their mental state—including to anxiety and distress—than the average person and hence may feel more need for coping assistance and affect dampening. These various possibilities all require further evaluation, but any one or several in combination would be important in tailoring smoking cessation strategies for maximal effectiveness for clients of psychiatric rehabilitation programs.

The focus groups highlighted environmental factors that may be important in designing prevention and cessation programs for this population. First, older clients may in the past have spent considerable time in hospitals and programs that routinely used cigarettes as rewards and placaters. Today access to "smoking privileges" or to cigarettes themselves is still sometimes used informally for behavior modification. Both encourage smoking and entwine it with the person's psychiatric history.

Second, participants in our focus groups described cigarette smoking as an important part of the informal social groupings and social exchange within their programs. Given the small social sphere of some psychiatric rehabilitation clients, this social aspect may provide a more powerful temptation to relapse or not to quit than it does for people who have access to a wider range of social outlets.

Third, participants noted hearing the message that they "shouldn't bother" to try to quit— "You have so many troubles, why worry about this one too," or "You have so few pleasures in your life, hold on to those you do have, including smoking." Such messages reinforce passivity and helplessness rather than encouraging self-care, fitness, and healthy life development, and they do not address the larger question of why the person has so many troubles and so few pleasures.