The terms used to refer to recipients of psychiatric services continue to be a source of controversy. Four terms in current use that represent different paradigms are "patient," "client," "consumer," and "survivor" (

1). Proponents of the "patient" paradigm consider users of psychiatric services to be mentally ill and to require care in a medical context. They dislike use of terms such as "client" and "consumer" because these terms imply human interaction in a business context rather than a healing context (

2). Opponents of the "patient" paradigm consider the negative connotations associated with the term—for example, sickness, disability, authoritarianism, and paternalism—and find its use inappropriate in rehabilitation, illness prevention, and health maintenance contexts. Proponents of the "client" paradigm consider the less passive connotation of the word and value its use in contexts of empowerment and collaboration between service providers and service users. Proponents of the "consumer" or "survivor" paradigm express similar concerns. In particular, those affiliated with the consumer empowerment movement argue in favor of use of the term "consumer" because it conveys a more activist and a hopeful stance than the traditional term "patient" (

3).

Shifts in terminology in mental health have in many ways paralleled changes in the relationship between providers and users in health care in general. Although the topic of appropriate terms has generated much debate, surprisingly little systematic research on the issue has been done. A 1996 U.S. survey of preferred terms for users of mental health services from a variety of settings suggested that no one term was clearly preferred among service users (

4). Forty-five percent of the sample preferred the term "client," 20 percent preferred "patient," and 8 percent preferred "consumer." On the other hand, Wing in 1997 surveyed persons attending a back pain clinic in Vancouver, Canada, and found that 74 percent of the sample preferred the term "patient" (

5).

In addition, little is known about the characteristics of service recipients who prefer one term over the others. Mueser and colleagues (

4) found no significant associations between the preferred term and gender, diagnosis, inpatient or outpatient status, or history of psychiatric hospitalization. On the other hand, Elliot and White (

6) reported an association between the preferred term and age; they found that preference for the term "patient" increased with age. Finally, the literature has focused on service recipients' preferences, and systematic surveys of service providers' preferences are lacking.

The purpose of the study reported here was to survey preferences for terms used to refer to users of psychiatric services among both service users and service providers and to identify factors that predicted the preferences. Examining terms used to refer to service users is important, given the connotations of particular terms and their implications for the delivery of high-quality care.

Results

Service providers

A total of 550 mental health service providers completed the service provider survey form. The majority of the mental health service providers were from the urban provincial psychiatric hospital (N=172, or 31.3 percent). The remaining service providers were from the urban private mental health center (N=129, or 23.5 percent), the rural provincial psychiatric hospital (N=119, or 21.6 percent), and the psychiatric unit in the urban health sciences center (N=59, or 10.7 percent). The location of 71 service provider respondents, or 12.9 percent, was not known.

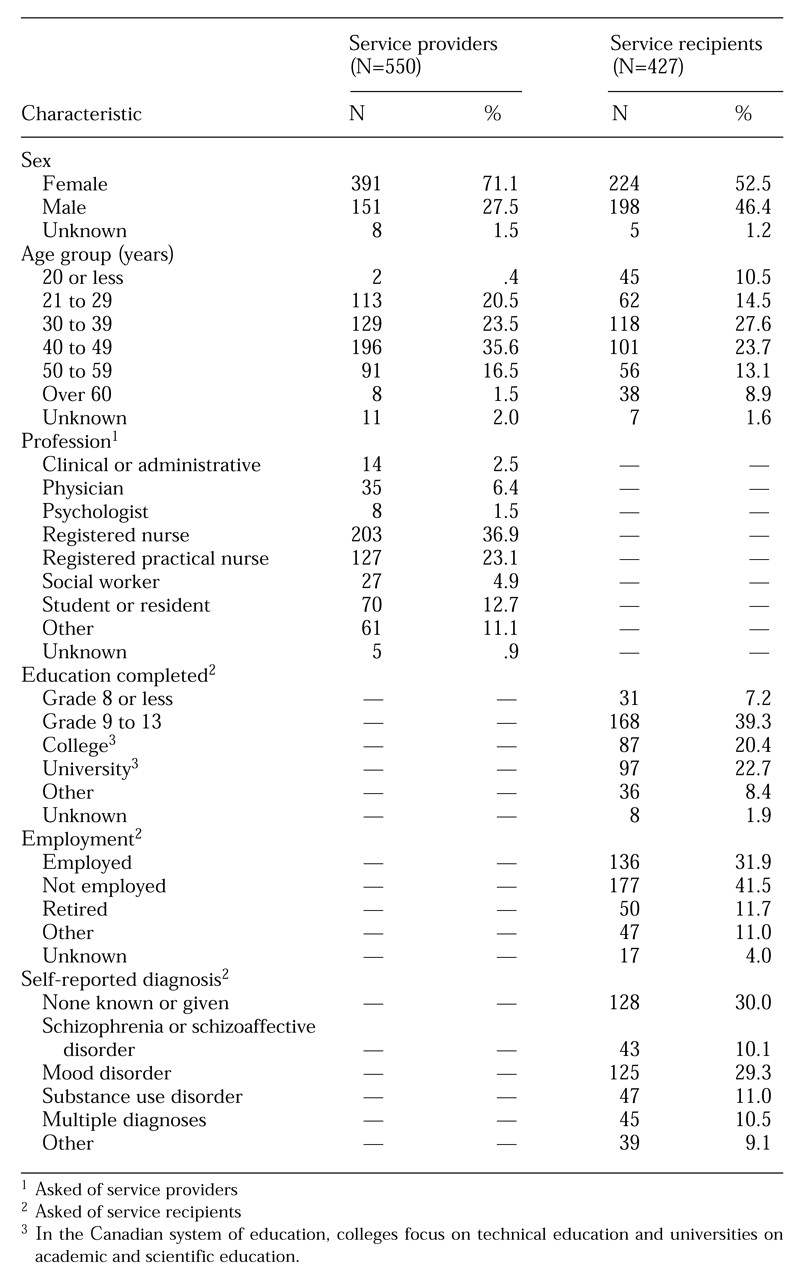

The sociodemographic characteristics of the mental health service providers are shown in

Table 1. The majority of the service providers were female (71.1 percent), were between ages 40 and 49 (35.6 percent), and were registered nurses by profession (36.9 percent). The group's mean length of service in the mental health field was 12.43±8.83 years.

A total of 68.4 percent of service providers preferred the term "patient," 26.5 percent preferred "client," 2 percent preferred "other" terms, and .5 percent preferred "consumer." The term "survivor" was not endorsed by any of the 550 service provider respondents. Similarly, the number of respondents who suggested terms other than those provided in the survey was very small (N=11). The following suggestions were given: the person's name, consumer-survivor, individual, treatment partner, people, person with psychiatric disabilities, and participants. Preferences were unknown for 2.5 percent of the service provider sample.

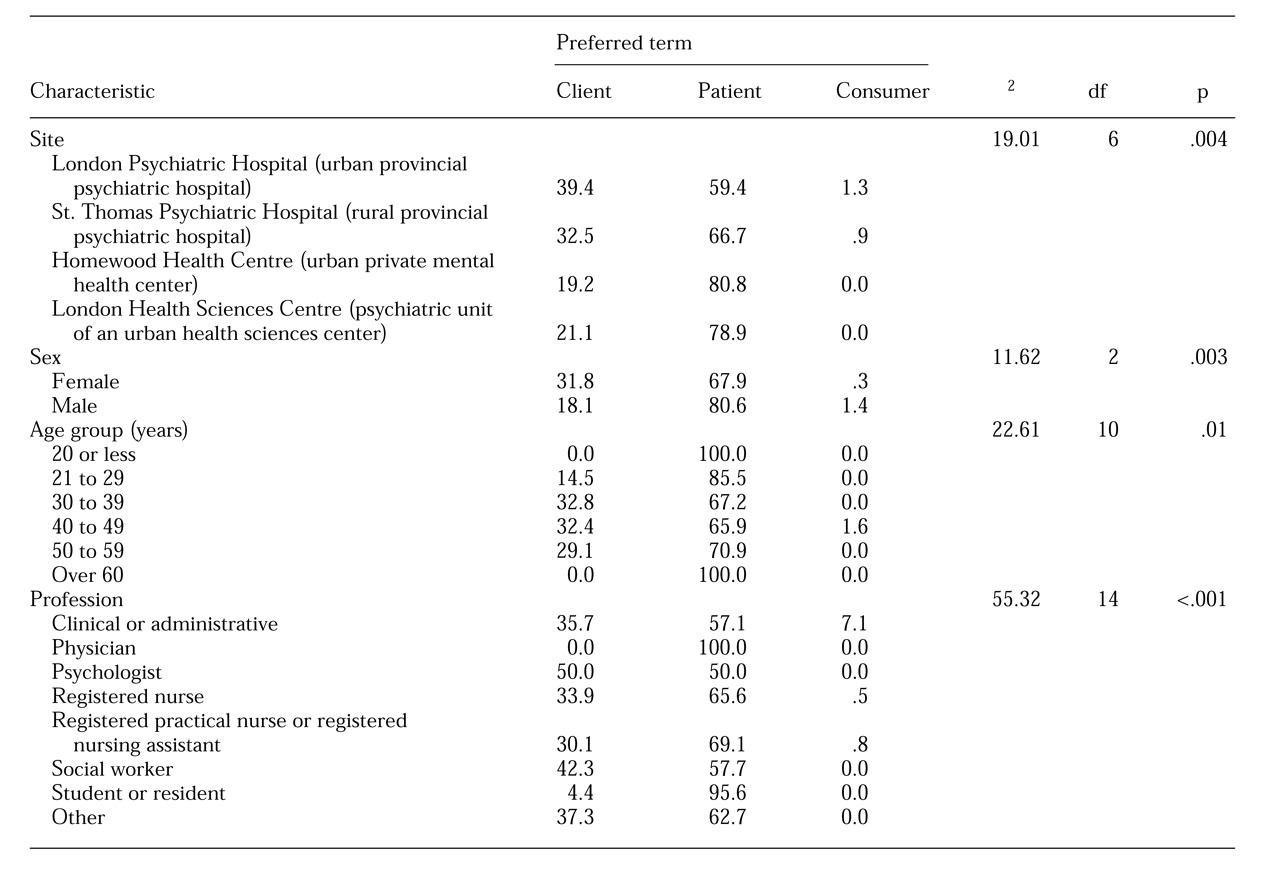

Because of the lack of endorsement of the term "survivor" and the heterogeneity of terms in the "other" category, both categories were excluded from further analyses of data from the service providers' surveys. Relationships between preferences of service providers for the three terms for service recipients and sociodemographic factors are presented in

Table 2. Service provider preferences were associated with site (χ

2=19.01, df=6, p<.004), gender (χ

2=11.62, df=2, p<.003), age group (χ

2=22.61, df=10, p<.012), and profession (χ

2=55.32, df=14, p<.001), but not length of service. Service providers who preferred the term "client" had a mean±SD of 13.02±7.65 years of service, those who preferred "patient" had a mean of 12.08±9.35 years of service, and those who preferred "consumer" had a mean of 14.67±5.69 years of service.

In relation to site, a larger proportion of service providers endorsed the term "client" in the provincial psychiatric hospitals than in the private and the general hospital psychiatric services. Women service providers were more likely to endorse the term "client" than were men service providers. On the other hand, younger service providers—those age 29 and younger—had a high rate of preference for the term "patient," as did physicians and students or residents.

Service recipients

A total of 427 mental health service recipients completed the service recipient survey form. The majority of the mental health service recipients were from the urban provincial psychiatric hospital (N=172, or 46.6 percent). The remaining service recipients who participated in the study were from the urban private mental health center (N=129, or 34.2 percent), the rural provincial psychiatric hospital (N=40, or 9.4 percent), and the psychiatric unit of the urban health sciences center (N=40, or 9.4 percent). The site for .5 percent of service recipients was not known.

The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the service recipients are summarized in

Table 1. The majority of the service recipients were female (52.5 percent), not employed (41.5 percent), and between ages 30 and 39 (27.6 percent). Most had completed secondary school (39.3 percent). Thirty percent reported that they had no known psychiatric diagnosis or had not been given a psychiatric diagnosis. Among those with a psychiatric diagnosis, mood disorders were the most frequently reported diagnoses; 14.5 percent reported having a diagnosis of depression, and 14.8 percent reported a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Substance abuse was reported by 11 percent, multiple diagnoses by 10.5 percent, and schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder by 10.1 percent. The mean number of psychiatric hospitalizations for the group was 6.32±8.8. More than half of the service recipients (N=234, or 54.8 percent) reported a history of physical, emotional, or sexual trauma.

A total of 54.8 percent of service recipients preferred the term "patient," 28.8 percent preferred "client," 7 percent preferred "survivor," and 2.8 percent preferred "consumer." Twenty-five service recipients, or 5.9 percent, suggested terms other than those provided in the survey, including first name, person, past client, customer, consumer-survivor, resident, and socially challenged care recipient. The preferences of .7 percent of the service recipients were unknown.

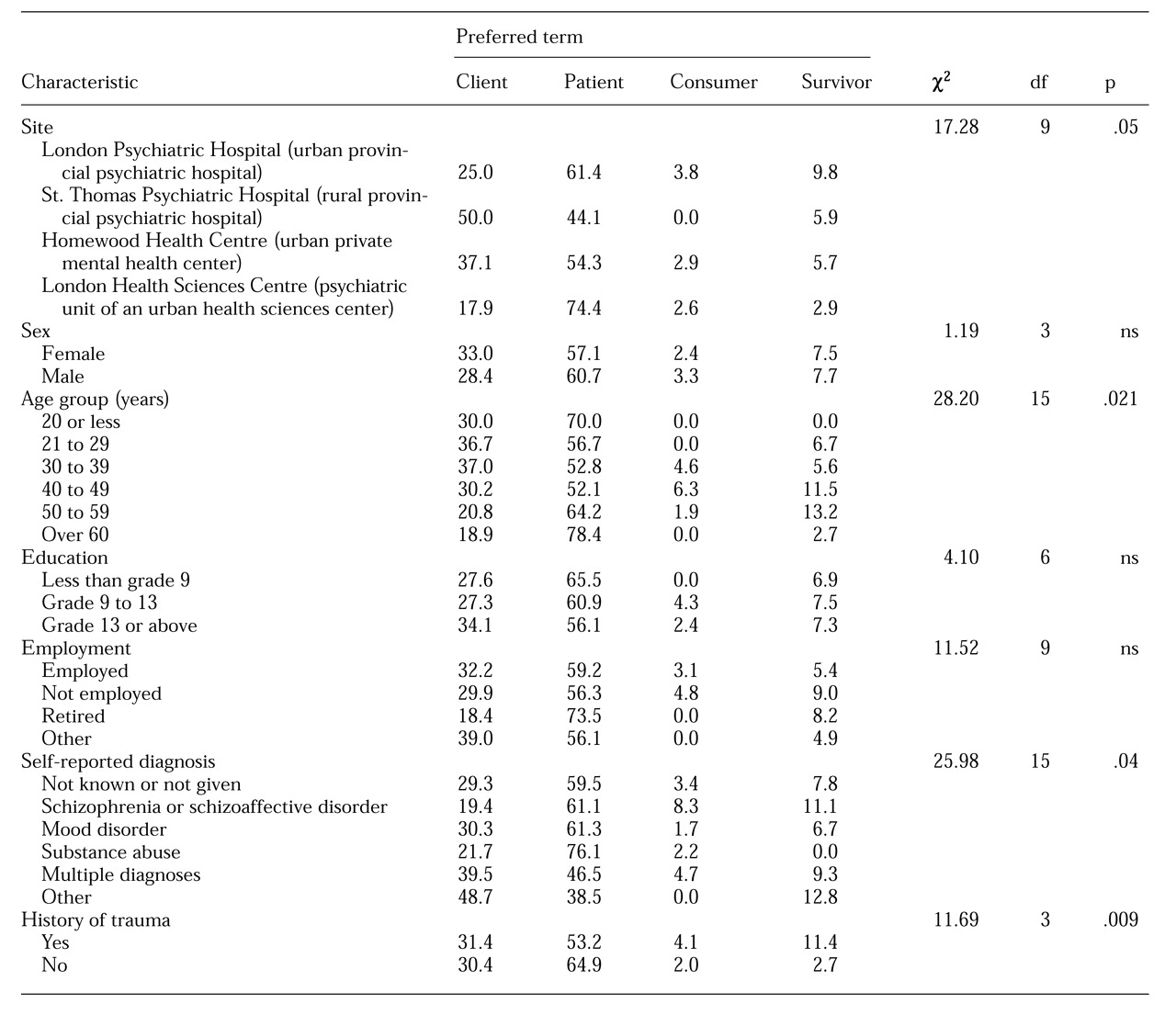

Table 3 summarizes the relationships between the terms preferred by service recipients and sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the sample. Service recipients' preferences were significantly associated with site (χ

2=17.28, df=9, p<.04), age (χ

2=28.20, df=15, p<.02), self-reported diagnosis (χ

2=25.98, df=15, p<.04), and history of trauma (χ

2=11.69, df=3, p<.009). Findings for gender, educational level, employment, and rate of self-reported number of hospitalizations were not significant. Service recipients who preferred the term "client" had a mean±SD of 5.36±7.22 hospitalizations, those who preferred "patient" had a mean of 6.96±10.44, those who preferred "consumer" had a mean of 5±2.77, and those who preferred "survivor" had a mean of 6.18±4.55.

In relation to site, more service recipients endorsed the term "client" in the provincial psychiatric hospitals and the private mental health center than in the general hospital psychiatric service. Service recipients age 60 and older and those with a self-reported diagnosis of substance abuse had a high rate of preference for the term "patient." Those between ages 40 and 59 and those with a diagnosis of a schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder preferred the term "survivor."

Predictors of preferred terms

Because the terms preferred by service recipients were significantly different from those preferred by service providers (χ

2=13.62, df=2, p<.001), separate logistic regression analyses (

7) were performed for service recipients and service providers to identify predictor factors. In the analysis of service providers' preferences, the variables site, age, female gender, years in profession, and professional status were entered into the logistic regression equations. For the site variable, data for the rural provincial psychiatric hospital, the private mental health center, and the psychiatric unit in the health sciences center were together compared with data for the urban provincial psychiatric hospital. For the professional status variable, data for the categories psychologist, social worker, registered nurse, registered practical nurse or registered nursing assistant, administrative staff, students or residents, and other were together compared with data for the physicians.

The logistic regression results for service providers' preference for the term "patient" showed that age and gender contributed most to prediction (χ2=13.59, df=2, p<.001). The findings suggested that younger service providers were more likely to prefer the term "patient," and that women service providers had lower odds of preferring the term "patient" than did men. The logistic regression results for service providers' preference for the term "client" also showed that age and gender contributed most to prediction (χ2=15.06, df=2, p<.001). These findings suggested that older service providers were more likely to prefer the term "client," and women had higher odds of preferring the term "client" than did men. The logistic regression analysis of service providers' preferences for the term "consumer" failed to provide any predictors, partly due to the small number of participants who preferred this term.

For the analysis of service recipient preferences for the term "patient," the variables site, age, self-reported diagnosis, and employment were entered into the logistic regression equation. For the diagnosis variable, data on participants with schizophrenia, substance abuse, multiple diagnosis, other diagnosis, and no diagnosis were together compared with data on participants with mood disorders. For the employment variable, data on participants who were not employed, retired, or had other employment arrangements were together compared with data for participants who were employed.

The logistic regression results for service recipients' preference for the term "patient" showed that the variables site, diagnosis, and employment status contributed the most to prediction (χ2=30.86, df=11, p<.001). More specifically, service recipients from the rural provincial psychiatric hospital had lower odds of preferring the term "patient" than did service recipients from the urban provincial psychiatric hospital. Service recipients with the diagnosis of substance abuse had higher odds of preferring the term "patient" than those with mood disorders. Retired service recipients were more likely to prefer the term "patient" than those who were employed.

The results for preference for the term "client" showed that site and diagnosis contributed most to prediction (χ2=28.97, df=8, p<.001). More specifically, service recipients from the rural provincial psychiatric hospital had higher odds of preferring the term "client" than service recipients from the urban provincial psychiatric hospital. Service recipients with the diagnosis of substance abuse had lower odds of preferring the term "client" than those with mood disorders. Finally, analysis of preference for the term "consumer" failed to provide any predictors, partly due to the small number of participants who preferred this term.

Discussion and conclusions

The survey results showed that service providers are more likely to prefer to refer to service recipients as patients than as clients or consumers. In this study physicians and students or residents were more likely to prefer the term "patient." However, logistic regression analysis showed that professional status did not predict preferred terms. Rather, age and gender contributed most to providers' preferences. Younger service providers—those age 29 and younger—were more likely to prefer the term "patient," and older service providers were more likely to prefer the term "client." These results seem counterintuitive, as it might be expected that older service providers would have a more traditional perspective on mental health care and may tend to prefer the term "patient." However, with experience and time, service providers may be influenced by the development of alternate perspectives and language choices.

Other factors related to the composition of the younger and older groups may also be important. In this study women service providers had higher odds of preferring the term "client." The gender difference could be explained by an overlap between the high proportions of women service providers (71.1 percent) and of registered nurses or registered nursing assistants (60 percent) in this survey. Because the nursing profession has adopted "client" as the more universal term (

8) and more nurses are female, more women may thus prefer "client."

Survey respondents from the provincial psychiatric hospitals were more likely to endorse the term "client" than were those in general and private hospital settings. This finding may be related to the recent adoption of client-centered principles in the provincial psychiatric hospital system. However, the provincial psychiatric hospitals have "patient councils" that include representatives who are service recipients, suggesting that the preferred term for service recipients may not be consistent. In the general hospital setting, the term "patient" was preferred, as would be expected in a medical setting. However, in the logistic regression analysis, site was not a predictive factor for preferred terms. A possible explanation is that factors other than site may override any possible site influences.

Service recipients in this study preferred the term "patient," followed by "client," "survivor," and "consumer." These findings are contrary to results from an earlier U.S. survey (

4) but are consistent with results of an earlier Canadian study (

5). There are several possible explanations for these differences. Systemic issues related to the differences in health care delivery between Canada and the United States may be a factor. Rada (

1) described a health care revolution in the U.S. in terms of a shift from "patient" to "client" to "consumer."

Characteristics of the service recipient population may also be an explanatory factor. In particular, the diagnostic profiles of service recipients in the study reported here differed from those of the earlier U.S. study (

4). In our study the reported rates of mood disorders and schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorders were 29.3 percent and 10.1 percent, respectively; the rates of those disorders in the U.S. study were 12.9 percent and 45.7 percent, respectively.

Differences in the settings surveyed may also be an explanatory factor. The U.S. study drew respondents from a greater diversity of settings than did our study. Settings in the U.S. study included inpatient psychiatric facilities, community mental health centers, psychosocial clubhouses, day treatment programs, vocational rehabilitation programs, and consumer-run drop-in centers.

For service recipients, the preference for the term "patient" was predicted by site, diagnosis, and employment status. For example, St. Thomas Psychiatric Hospital, the rural provincial psychiatric hospital that participated in the study, has adopted a psychosocial rehabilitation model that reinforces the use of the term "client."

Survey respondents with a diagnosis of substance abuse had higher odds of preferring the term "patient" than those with mood disorders. This finding is contradictory to the hypothesis that the term "client" may be preferred in the addictions model of treatment. However, both sites in this study that offered substance abuse treatment programs are inpatient units in psychiatric facilities, and one of those sites has a mandate to deliver substance abuse treatment to those with dual diagnoses of psychiatric disorder and substance abuse.

The preference of retired service recipients for the term "patient" may be more related to their age than to their employment status. Our analysis found no factors that predicted preference for the term "client" or for the term "consumer." The small number of respondents who endorsed those terms may have precluded meaningful prediction.

The findings of this survey contribute to the literature on the preferences of terms for mental health service recipients among both the recipients and the providers of mental health services. Although preferences have been identified in the survey, neither service providers nor recipients showed a clear and consistent preference for particular terms. This finding supports the need for dialogue between recipients and providers on the terms used (

4). In particular, the dialogue may focus on a particular recipient's preference as well as the implication for various terms on the working relationship between recipient and provider.

In addition, providers of mental health services may need to discuss the terms used in their program and facility as well as their implications. Use of a term may be context-dependent—for example, the term "patient" may be appropriate for someone who is in an intensive care unit. On the other hand, someone who is in a rehabilitation phase of treatment would be appropriately addressed as a "client." As changes occur in the health care system, the terms used to refer to service recipients will need to be reexamined, and service recipients will undoubtedly participate in these endeavors. As suggested by Rada (

1), the concept of "partners in care" moves the recipient of care into an active role in the enterprise of health and well-being.