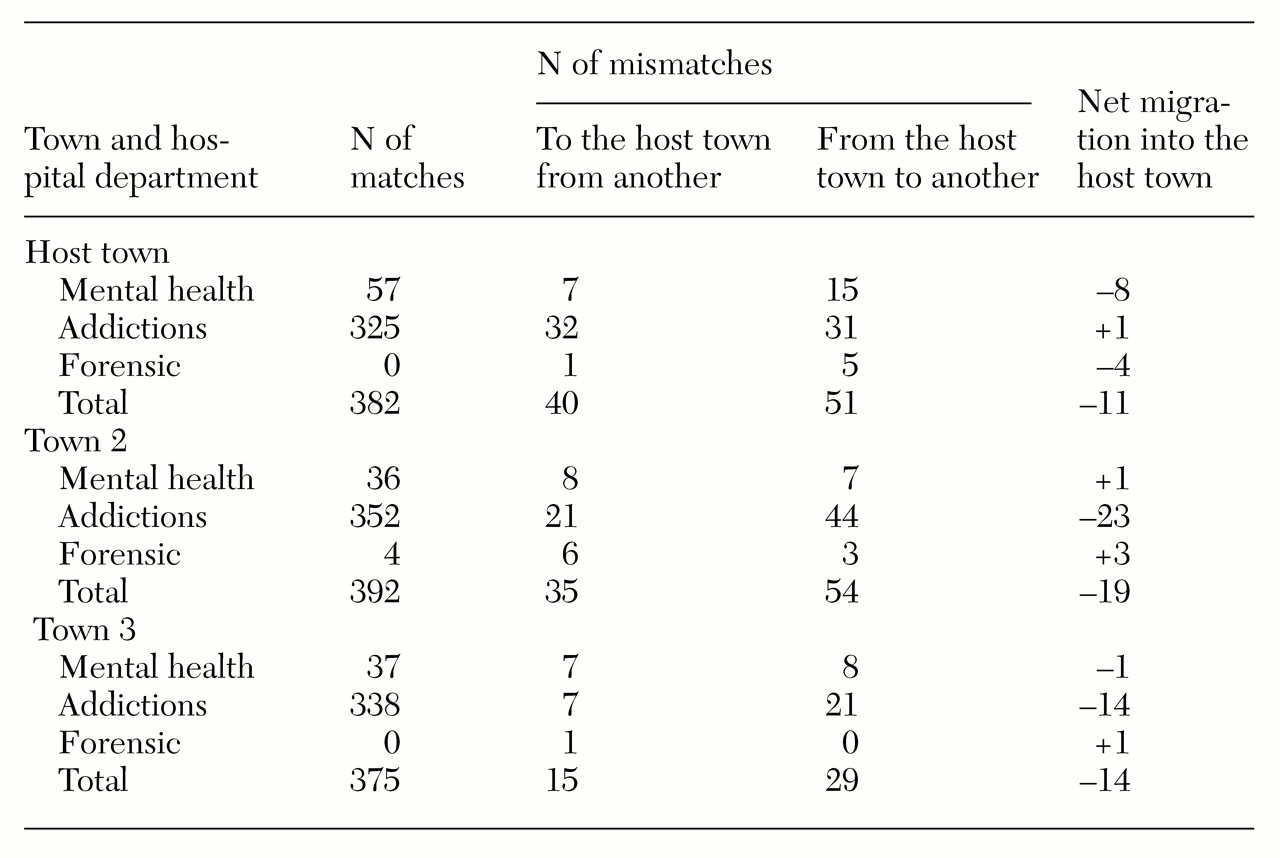

Overall, the incremental economic impact of the consolidation plan on the host community was positive. The added net benefit to the community of the consolidation was estimated at roughly $3.9 million (in 1997 dollars) for the 18-month period after consolidation. This benefit would recur—that is, it was estimated that the community would gain this amount every 18 months.

Objective socioeconomic impact

With the exception of the hospital's response to patients who left the hospital without permission, the hospital's practices after consolidation either contributed positively to the socioeconomic welfare of the community or had no effect, compared with practices in the 18-month period before consolidation.

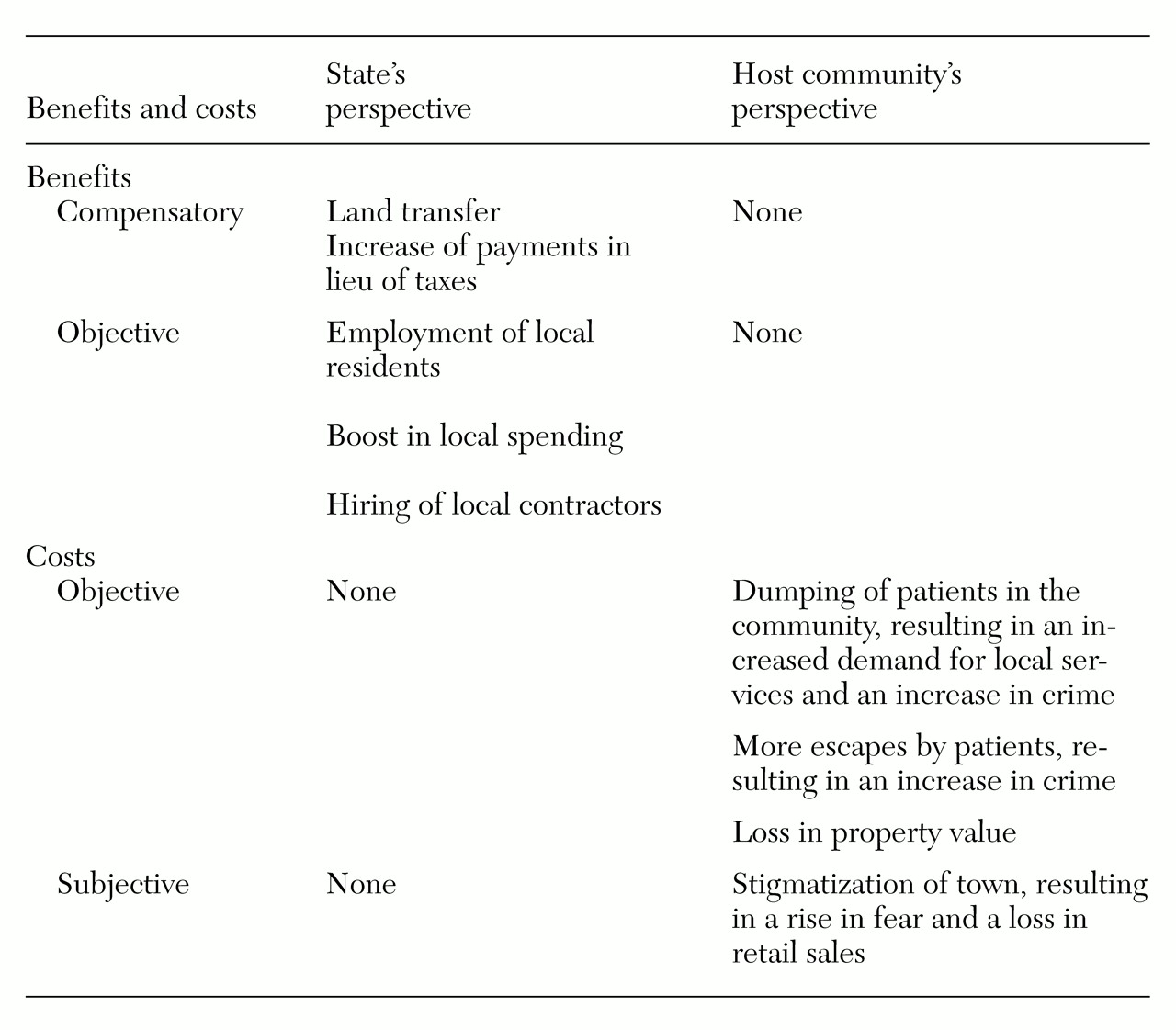

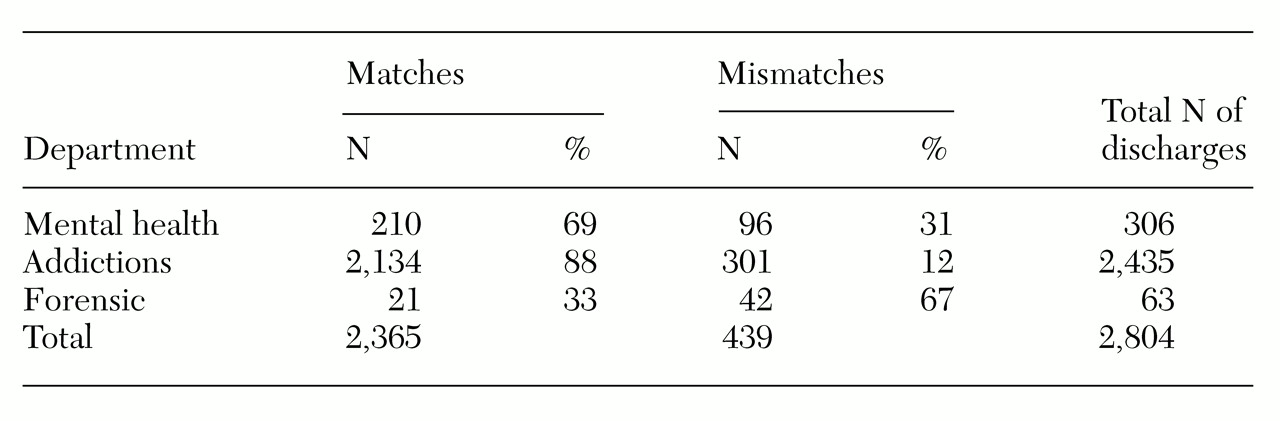

Discharge policies and practices. The hospital's discharge policy was to return patients ready for discharge back to their home community unless such a placement imposed risks to the patient. Consistent with these policies, 84 percent of patients discharged from the hospital in the 18 months after consolidation were discharged to their town of origin (

Table 2). The host town had a mismatched discharge score of -11, meaning that among the mismatched discharges, 11 more patients from the host town were placed in some other town (

Table 3).

Logistic regression was used to identify predictors of mismatches. Neither being from the host town nor being discharged to the host town was a significant predictor. Findings based on hospital discharge records were confirmed by the community-based investigation.

Local service use. Local providers expected a huge surge in the need for their services after the consolidation. The medical director of the local emergency room anticipated that consolidation would be a "cataclysmic event" and that the hospital would be "deluged with patients." Similarly, the vice-president of a large nonprofit alcohol treatment facility in the town "expected floods." Yet, in retrospect, these agencies reported that consolidation had been "a nonevent."

Other service providers shared this view. Officials of the local housing programs said they were not receiving referrals from the hospital, were receiving fewer referrals after consolidation, or were receiving referrals only for clients who were residents of the host town. Service utilization data from the periods before and after the consolidation supported these perceptions.

Similar reports were provided by locally funded service agencies. The superintendent of the school system reported that consolidation "had no effect on education." The acting police chief claimed that there had been "no noticeable change in the nature or volume of interactions between the police and persons with mental illness over the past two years." His perception was consistent with the local crime statistics.

Residency history of street persons. According to hospital records, only 21 of the 133 street people surveyed (16 percent) had been patients of the hospital during the past two years. Most of these (17, or 81 percent) were former patients of the addictions department. Fourteen of the former patients (67 percent) had lived in the host town longer than two years. Fourteen of the former patients had been placed back in their town of origin, the host town, at the time of discharge. Of the seven patients (33 percent) who were not from the host town at the time of admission, only one had been discharged to the host town, because his parents were living there.

Security practice. Of the 3,036 admissions to the hospital in the 18 months after consolidation, 33 patients (1 percent) left the grounds of the hospital without permission. Patients who were on leave in other communities and who did not return to the hospital were not counted among those absent without leave. For the host town, the adjusted rate of absence-without-leave events was 1.1 per 100 admissions. The host town's exposure to unauthorized absences decreased by less than one patient (a decrease of .6) in the 18 months after consolidation. This finding was confirmed by the acting police chief, who reported that the level of police resources used to apprehend patients who left the hospital without permission had not changed since consolidation.

Employment practices. With consolidation, the number of employees of the hospital increased by 61 percent, to 1,336. In the month before consolidation, 14 percent of the annual hospital payroll went to the 200 employees who resided in the host town. By contrast, in the last month of the study period, 320 employees residing in the host town received 24 percent of the annual payroll.

Local purchases by the hospital. The hospital made purchases both for operations and for the renovation. Overall, payments to businesses in the host town increased 10 percent with the advent of consolidation. That is, payments to local businesses from the hospital increased by approximately $315,000 in the year after consolidation, and these payments were distributed to 99 local businesses. During the 18-month period, the incremental increase in total local purchases was estimated at $472,500.

Local purchases by new employees. The average new employee reported spending $91 a week in the host town. To the extent that the surveyed sample is representative of all new employees, consolidation added approximately $45,900 to retail sales of local businesses every week. New employees also reported spending, on average, another $322 for services and durable goods from local businesses every six months. Based on this average expenditure, estimated local expenditures for services and durable goods by all new employees equaled $162,288 every six months. Overall, it was estimated that new employees would add a total of $4.1 million to local retail sales every 18 months.

Subjective socioeconomic impact

A small segment of the community believed that the consolidation plan had harmed the welfare of the community.

Residential perceptions. A total of 640 of the 800 respondents from the host town (80 percent) thought that the town as a place to live either had improved or had not changed over had the past two years. When asked specifically about the changes in the downtown shopping area, 304 respondents (38 percent) said that the downtown area had become worse since consolidation. Almost a quarter of these residents said that what they liked least about the downtown area was that too many people were homeless (80 respondents, or 10 percent) or mentally ill (16 respondents, or 2 percent) and that the streets were not safe (80 respondents, or 10 percent). When asked why there was homelessness in their community, 176 of the town residents (22 percent) attributed the increase to the impact of the hospital—104 (13 percent) cited the discharge of patients into town from the hospital and 72 (9 percent) cited the social services provided by the community.

Shopping behavior. Sixteen of the 800 residents surveyed (2 percent) said that what they least liked about the downtown area was that there were "too many mentally ill people downtown." It was estimated that these 16 residents would each spend $184 more per month downtown if people with mental illness were not in the downtown area. Based on these estimates, the retail sales potential per month associated with eliminating the presence of persons with mental illness in the downtown area was $62,773, or $1.1 million for the 18-month period.

Merchants' perceptions. The 25 merchant respondents were divided in their assessment of how the retail activity in the downtown area had changed over the past two years. Ten merchants (40 percent) said that the downtown area had not changed. Nine merchants (36 percent) reported a decline in retail activity, and seven of them attributed it to poor economic conditions in the state. Three merchants (12 percent) attributed the decline in retail activity to the "atmosphere" of the downtown area. In particular, they mentioned "the crazies walking around," the "bad reputation" of the downtown area, and "too many drugs in the area."