Clinicians are becoming increasingly aware of the need to better understand the sexual lives of persons with severe mental illness, partly because of the impact of the HIV epidemic on this population (

1). However, both clinical work and HIV prevention research are limited by reliance on self-reports about sexual risk behaviors, which are of uncertain reliability.

Although studies suggest that carefully designed interviews can elicit reliable sexual histories from some populations (

2,

3), the reliability of such data among persons with severe mental illness is not well established. Several factors that may undermine reliability, including cognitive impairment, substance use, and a history of sexual abuse, are common among mentally ill individuals (

4). Despite these factors, a previous study of the reliability of data provided by 25 psychiatric patients about their sexual behavior reported encouraging results (

5). In the study reported here, we built on the previous study, using a larger sample and covering a more comprehensive range of risk behaviors.

Methods

The study was conducted in a psychiatric program in a municipal men's shelter in New York City. Subjects were recruited from the 122 patients who participated in a larger study of HIV risk behaviors (

6). Data collection was completed in August 1993. Thirty-nine men consecutively enrolled in the risk behaviors study were asked to also participate in the reliability study reported here. All of them agreed and provided written informed consent.

Sexual behavior data were obtained using a version of the Sexual Risk Behavior Assessment Schedule (SERBAS) (

7) that was adapted for homeless men with severe mental illness. The SERBAS is a semistructured interview, consisting of 281 items, which first screens for sexual activity and then assesses recent and lifetime sexual practices in detail. The terminology about sexual behavior used in the interview is established with the respondent at the beginning of the interview. The length of the interview varies according to the amount and type of sexual behavior reported; in this study interviews lasted an average of one hour. For this study, only data from items inquiring about sexual behaviors in the past six months that might be related to HIV transmission were used.

The SERBAS was administered to each participant twice, one to two weeks apart, by two different male interviewers. Both interviewers were nonclinicians; one had a bachelor's degree and one a Ph.D. degree. The interviewers were trained using a standard protocol that included desensitization to sexual talk, didactic sessions on sexual interviewing, and supervised pilot interviews. Interviews were conducted in private rooms, and strict confidentiality was assured.

We chose a one- to two-week interval between interviews so that most of the men would still be living in the shelter for the second interview, which both simplified follow-up and prevented the possibility that changes in settings might affect the reliability of results. In addition, the items used in this study ask about sexual behaviors over the past six months. A relatively short interval between the two interviews ensured that the interviews largely covered the same time.

Demographic data were collected at the first interview using a personal history assessment developed for research in this population. Psychiatric and lifetime substance use diagnoses were made at a later time by clinical interviewers using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (

8). Both instruments have been used in previous studies of homeless men with severe mental illness.

We assessed the test-retest reliability of self-reports of recent sexual behaviors related to HIV transmission. First, we compared responses from the two interviews about any sexual activity, sex with women, and sex with men. Second, we assessed the reliability of data on the number of female and male sexual partners, including all partners, new partners (those with whom the first sexual contact was made within the past six months), and commercial partners (those with whom drugs or money was exchanged for sex). Third, we assessed the reliability of the data on specific sexual behaviors, including the number of episodes, the percentage of episodes that included vaginal and anal intercourse, and the percentage of each type of behavior that was condom protected. Reliability was estimated using kappa and intraclass correlation coefficients (

9).

Results

Of the 39 men in the study, 32 (82 percent) were African American, six (15 percent) were Latino, and one (3 percent) was white. Their ages ranged from 24 to 57 years. Thirty of the men (77 percent) had schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, seven (18 percent) had major depression, and two (5 percent) had other psychotic disorders. Twenty-three (59 percent) were diagnosed as having comorbid cocaine or alcohol use disorders. Twenty (51 percent) had been homeless for at least one year.

Twenty-six men reported any sexual activity during the previous six months: 22 at both interviews, three at the first interview only, and one at the second interview only (kappa=.78). Twenty-three reported sex with women: 17 at both interviews, four at the first only, and two at the second only (kappa=.69). Nine reported sex with men: eight at both interviews and one at the second interview only (kappa=.93).

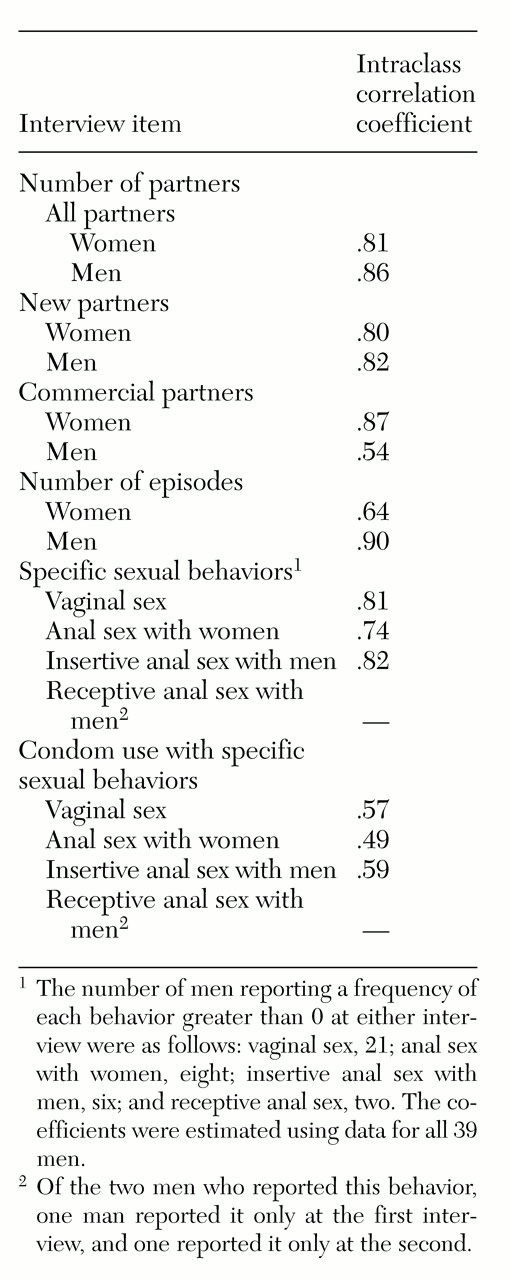

Table 1 shows intraclass correlation coefficients for the number of partners and episodes and the frequency of specific sexual behaviors reported at the two interviews. Although standards for judging reliability estimates vary, in general, estimates below .4 represent poor reliability, those between .4 and .75 represent good reliability, and those above .75 represent excellent reliability (

9). In this study, reliability estimates ranged from .49 to .90 for all behaviors except receptive anal sex with men. The number of men reporting this behavior was too low to estimate reliability.

We conducted subsequent analyses, first restricting the sample to the 26 men who reported sexual activity at either interview and then restricting it to the 22 men who reported sexual activity at both interviews. The results were essentially the same. Restricting the sample to the subsample of men with substance use diagnoses also did not change the results.

Conclusions

The findings of this study indicate that it is possible to elicit reliable information about sexual behavior from homeless men with severe mental illness. Men from this population might be expected to have difficulty remembering and reporting their sexual behaviors because, in addition to psychiatric disorders, they commonly have substance use disorders, long-standing histories of homelessness, and unstable sexual relationships. Yet by common standards (

9), reliability was adequate for most behaviors.

These data provide important support for the promising results from studies of interventions to reduce HIV risk among men with severe mental illness, which have been based on self-report data (

10). However, our reliability estimates for some behaviors were lower than those reported for less marginalized populations (

2,

3). This finding should be considered when planning sample sizes for intervention studies in this population and when making comparisons of risk behaviors between this population and others.

The lowest reliability estimates were for the number of male commercial sex partners and the frequency of receptive anal sex. Both practices are stigmatized behaviors in this population, which may make them more likely to be underreported. For other behaviors, the reliability of reports of condom use (range, .49 to .59) was generally lower than the reliability of reports of other specific sexual behaviors (range, .74 to .82), perhaps because questions about condom use were more complex. For these questions, the men were asked to report what percentage of their sexual episodes included each specific behavior. They were then asked for what percentage of these estimates the behavior was condom protected.

Our study had important limitations. The sample included only men. The reliability of sexual history reports may differ for women with severe mental illness. The sample size was too small to draw conclusions about less common sexual behaviors. The period covered by each interview—the past six months—did not completely overlap, which might explain some of the inconsistency between the two interviews. Finally, reliability is a necessary but not sufficient prerequisite of validity; establishing the validity of self-reports about sexual behavior of persons with severe mental illness will be more difficult.

It is also noteworthy that administering the SERBAS interview requires considerable training, from 15 to 20 hours. Interviewers with less training might not achieve the same reliability.

Further examination of these data revealed ways to improve interviews about sexual behavior for this population, particularly about stigmatized behaviors and condom use. Such improvements include shortening the period of time covered by the interview questions, asking subjects to report behaviors with each of their partners separately, and asking subjects to report frequencies for each behavior by counts instead of percentages.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by grants MH-49547, MH-48041, and P50-MH-43520 (Anke A. Ehrhardt, Ph.D., principal investigator) from the National Institute of Mental Health and by the Aaron Diamond Foundation (to Dr. Colson).