For the sake of discussion, treatment for the dually diagnosed patient can be divided into two phases: acute treatment and stabilization, and maintenance and rehabilitation. The assessment and classification issues relevant to these phases differ and will be discussed separately.

Acute treatment and stabilization

This initial phase of treatment begins with the first contact with the patient and can last for several weeks or months. Treatment during this phase includes observation, management of acute intoxication and withdrawal, management of acute psychiatric symptoms, and restabilization of the patient to a baseline condition.

The first assessment task from the standpoint of dual diagnosis is to evaluate the possibility that the patient has both substance abuse and psychiatric problems. Does the patient show psychiatric symptoms and evidence of substance intoxication or withdrawal? If so, do the psychiatric symptoms clear as detoxification proceeds? If the psychiatric symptoms clear completely with detoxification and the patient has no prior history of psychiatric disorder, then the patient should not receive a dual diagnosis. Conversely, if the psychiatric symptoms do not fully abate with detoxification or if the patient has a prior history of psychiatric illness, then the possibility of dual diagnosis should be considered.

One major pitfall during this initial assessment phase is the failure to adequately consider the possibility of both problems, to either overlook or misattribute the symptoms of one of the disorders to the other. DSM-III-R offers a clear and systematic framework for assessing the presence of substance abuse and psychiatric syndromes. Clinicians should be conversant with the DSM-III-R criteria for mental disorders and substance abuse disorders and apply them in a thorough initial evaluation. Lack of familiarity with this or some other well-defined set of criteria may lead to premature closure about the presence of either type of problem.

A second major pitfall during the assessment phase is to presume the primacy of either the psychiatric or the substance abuse disorder. Despite the shortage of empirical data to guide us, there seems a consensus in the literature that this phase of treatment should include concurrent treatment for both disorders (

22). This approach avoids the disjointed treatment so often encountered by these patients, who are referred back and forth between psychiatric and substance abuse treatment programs that view one of the disorders as primary and argue that the other cannot be addressed until the first is stabilized. It is not clear whether patients can be effectively treated by involvement in both types of programs simultaneously or whether hybrid programs are needed (

22). In any event, the key to assessment and treatment in this phase is to identify and treat all syndromes present.

At first glance it would seem a relatively easy task, given careful and thorough assessment, to decide which patients have a dual diagnosis and to establish which syndromes are present, but this is not always the case. Persons with well-documented histories of a major mental illness plus well-documented histories of alcoholism or drug dependence fall clearly into the realm of dual diagnosis. Patients experiencing transient psychiatric symptoms clearly attributable to intoxication or withdrawal would not receive a dual diagnosis. However, clinicians encounter more difficulty when considering less definitive or more chronic levels of psychiatric symptoms and substance abuse.

For example, the following types of patients are examples of less clear candidates for dual diagnosis: a person with an episode of major depression who drinks alcohol while depressed; a person with manic-depressive illness who drinks when manic; a person with schizophrenia who takes stimulants, perhaps to counteract neuroleptic side effects or the negative symptoms of schizophrenia; a person who abuses amphetamines, intermittently becomes psychotic, and is dysphoric without stimulants; and a person with alcoholism who develops persistent first-rank symptoms of schizophrenia in the postwithdrawal phase. Put more generally, when does the use of psychoactive substances constitute abuse among the mentally ill and when should psychiatric symptoms among substance abusers be considered mental illness? Currently it is not evident where to draw the line or even if the assumption of such a line is valid.

Given current concerns about the tendency to overlook the existence of dual problems, the most prudent recommendation is to attend carefully to the presence of any persistent psychiatric symptoms and any persistent substance abuse. Thus the two major recommendations for assessment of dual diagnosis patients during acute treatment and stabilization are to conduct a thorough examination for both types of disorders and to avoid premature decisions about which disorder might be primary.

Maintenance and rehabilitation

Maintenance and rehabilitation is a long-term phase of treatment that seeks to prevent recurrence of the disorders through continued medical and psychosocial interventions. Such interventions may include the broad array of services offered to persons with either substance abuse or mental illness: medications, psychotherapy, self-help, and rehabilitation. The key question during assessment and classification of what long-term treatments are necessary becomes more relevant in this phase to ascertain whether the patient's disorders have a hierarchical structure and what factors contribute to the long-term risk of recurrence. During this phase, a variety of clinical hypotheses about how the patient has come to be dually diagnosed gain relevance.

The clinician may need to address various treatment questions. Does the patient need maintenance pharmacotherapy for mental illness (neuroleptics, antidepressants, or lithium), for substance abuse (disulfiram or methadone), or for both? Would the patient benefit from psychosocial treatments, and if so, which ones? Patients with psychotic disorders may not do well in standard substance abuse self-help programs, and persons with primary substance abuse problems may not fit well into psychosocial programs for the seriously mentally ill. The vocational rehabilitation needs of persons suffering from psychotic disorders with secondary alcohol abuse may differ from those of alcoholics with intermittent psychotic symptoms associated with intoxication or withdrawal. Decisions about long-term treatment will depend on the clinician's hypothesis about why a given patient is dually diagnosed.

Following are discussions of four clinical hypotheses about how dual diagnosis conditions develop: primary mental illness with substance abuse sequelae, primary substance abuse with psychiatric sequelae, dual primary diagnosis, and common etiology. They are mutually exclusive in a given case, but different hypotheses probably account for different segments of the dually diagnosed population. The four hypotheses also are not necessarily the only possible hypotheses, but they illustrate the kinds of clinical reasoning inherent to many current discussions of the dually diagnosed. All are longitudinal hypotheses about illness, in contrast to the cross-sectional, phenomenologic diagnostic approach needed in the earlier phase of treatment.

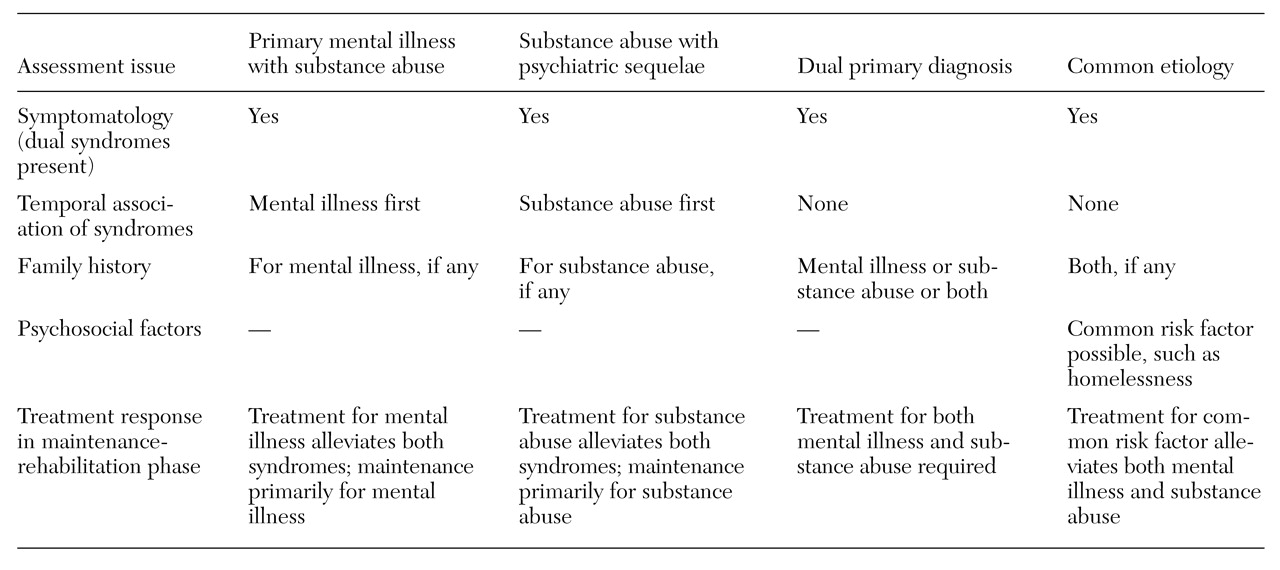

Table 1 summarizes the types of assessments that may be helpful in classifying patients according to these four clinical hypotheses.

Primary mental illness with substance abuse sequelae. In this hypothesis, the patient suffers from a primary mental illness, and the symptoms and sequelae of the illness or its treatment (for example, medication side effects) lead to addictive behavior as a way of coping with the illness. This hypothesis encompasses the concept of self-medication (

23,

24,

25) but also covers secondary substance abuse attributable to such factors as impaired judgment and social passivity.

The literature on risk factors for addictive behavior is striking for the fact that most of the risk factors are present with mental illness (

26). Risk factors for addictive behavior include negative affect states, impaired cognition, misinterpretation of internal cues, poor self-esteem, lack of a sense of self-control and self-efficacy, poor role performance, impaired social skills, restricted coping capacities, disturbances of vegetative functions, and lack of social supports.

Given this literature, it should come as no surprise that the mentally ill suffer from high rates of substance abuse. The risk of addictive behavior may be increased via multiple nonspecific symptoms and sequelae of mental illness. For example, the dysphoria, demoralization, loss of self-esteem, and loss of functioning associated with many persistent mental illnesses may lead to a nonspecific search for relief in abused substances. Such a scenario would not entail an association between specific mental disorders and specific substances of abuse.

Some of the literature supports a second, more specific self-medication hypothesis (

2,

25,

27). Certain mental illnesses may predispose patients to abuse specific substances that in some way alleviate the immediate negative effects of that mental illness. Numerous possible examples are reported in the literature, including an increased association of psychostimulant abuse with psychotic disorders (

15,

27,

28) and of abuse of alcohol and other central nervous system depressants with affective disorders (

15,

29,

30). However, other reports counter these patterns (

8,

25,

31,

32), so the data on consistent associations between specific mental disorders and specific types of substance abuse are by no means conclusive.

The self-medication hypothesis may provide some intriguing clues to the underlying pathophysiology of various mental illnesses. For example, Cesarec and Nyman (

33) found differential responses to amphetamines among different subgroups of schizophrenic patients; patients with only deficit symptoms of schizophrenia tended to improve on a combination of neuroleptic and amphetamine, whereas those with active psychotic symptoms worsened. Perhaps differences in substance abuse patterns among patients within a given

DSM-III-R diagnosis could provide useful clues to differentiating physiologically heterogeneous subtypes.

DiSalver (

30) has proposed that the substances typically abused by patients with affective disorders may provide clues to the pathophysiologies of these disorders, and he specifically proposes a connection between abuse of anticholinergic substances and the monoamine theory of affective disorders. Khantzian (

25) has provided specific psychodynamic hypotheses linking the abuse of heroin and cocaine to specific psychiatric syndromes. It is not currently known whether such lines of speculation will yield useful information for future classification.

The implications of this hypothesis for maintenance and rehabilitation for such a patient are that the principal focus of treatment will be on alleviating the symptoms and sequelae of the mental illness, with the assumption that the sustained amelioration of these symptoms and sequelae will lead to resolution of the substance abuse. Most likely such a patient would be treated by the mental health care system in the long term. However, if dependency on the substance has developed, the substance abuse may need to be treated as a primary problem in its own right.

Primary substance abuse with psychiatric sequelae. This hypothesis holds that the patient suffers primarily from substance abuse and that psychiatric symptoms are a manifestation of the effects of the substance(s) abused. Examples include the rebound depression in the use of cocaine and other stimulants (

34), impairments in cognitive functioning and thought processes due to alcohol (

35), psychoses induced by phencyclidine, amphetamine, lysergic acid diethylamide, and other psychotomimetics (

36,

37). This hypothesis covers the acute psychiatric syndromes associated with intoxication and withdrawal, and such cases can usually be recognized as not true dual diagnosis as the patient becomes detoxified.

A more intriguing and elusive question is whether primary substance abuse can lead to persistent mental illness in the absence of continued substance abuse. Some evidence does support this hypothesis, including the chronic psychotic states associated with long-term abuse of stimulants (

38,

39,

40) and persistent affective disorders related to abuse of central nervous system depressants and other agents (

30,

38).

Whether these patterns of persistent mental disorders following primary substance abuse are the result of a preexisting vulnerability to mental illness uncovered by the substance abuse or of persistent changes in brain physiology directly attributable to the abused substance remains an open issue. Patients fitting this hypothesis may receive maintenance and rehabilitation primarily in substance abuse programs.

Dual primary diagnosis. Under the hypothesis of dual primary diagnosis, the patient suffers from two initially unrelated disorders that may interact to exacerbate each other. The apparent increased co-occurrence of mental illness and substance abuse above that predicted by chance tends to argue against this hypothesis (

2). However, this model may apply to some subgroups. For example, studies generally have not found an excess prevalence of alcoholism among patients with schizophrenia (

28,

41,

42), although even this finding has not been entirely consistent in the literature (

2). The particular relevance of this model is that even co-occurrence of primary psychiatric and substance abuse disorders may alter the presentation of either, making diagnosis and treatment more difficult.

The treatment implication for this hypothesis is that such dually diagnosed patients will need maintenance and rehabilitation for both psychiatric and substance abuse disorders. They will require either parallel treatment in both the mental health and substance abuse service sectors or treatment in a "hybrid" program (

22).

Common etiology. The hypothesis of common etiology posits that common underlying factors may predispose a patient both to mental disorders and to substance abuse disorders. Certainly the most common example is the idea that alcoholism and affective disorders are familially linked (

43,

44,

45), but there is dispute about whether this connection indicates a common underlying genetic factor (

32) or other phenomena, such as assortative mating (

46).

Regardless of whether a genetic link exists, some dual disorders may share a common biologic etiology. Defects in dopaminergic function may predispose patients to schizophrenia and to abuse of such dopamine agonists as amphetamine (

33). Similarly, defects in cholinergic activity may predispose patients to affective disorders and to abuse of drugs affecting cholinergic pathways (

30). Finally, one may postulate common psychosocial factors that predispose to mental illness and to substance abuse, such as homelessness as a risk factor for both depression and substance abuse (

47).

The treatment implication of the hypothesis of common etiology is that if such a common underlying etiologic factor exists, the treatment should be aimed at this factor. Presumably, effective intervention with this factor will alleviate both the psychiatric and substance abuse disorders.