Introduction by the column editors: The specificity of the different curricula used for training persons with schizophrenia in the wide spectrum of skills they need is both a strength and a limitation. By separately teaching skills for each domain of community adaptation, clinicians using behavioral learning principles have overcome most symptomatic and cognitive barriers to learning. It is axiomatic in behavior therapy that "you get what you teach"; hence it has been necessary to adopt arduous training in many areas to bring about improvements in social functioning (

1).

Although social skills training has yielded excellent acquisition and durability of skills, generalization to other domains of functioning has to be carefully programmed. One way to promote generalization is to teach persons with schizophrenia a general social problem-solving method. In the modules for training social and independent living skills produced by Liberman's UCLA group, problem solving is embedded in two of the eight learning activities for each skill area, which may account for the durability and generalization of skills reported in recent studies of the modules (

2,

3,

4). Information about the modules for teaching social and independent living skills is available on the Web site of Psychiatric Rehabilitation Consultants at www.psychrehab.com.

Problem solving is a core element in a wide variety of interventions for anxiety, mood, and schizophrenia spectrum disorders (

5,

6). Developing the ability to identify and cope with stressors, interpersonal conflicts, and other obstacles blocking achievement of goals is a key aspect of most psychological treatments. We describe a module for teaching interpersonal problem-solving skills, its use with outpatients who have schizophrenia, and the impact of the training as measured by the Assessment of Interpersonal Problem Solving Skills (

7).

Evaluation of the module

Sample

Participants were 75 individuals with a

DSM-III-R diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder confirmed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) and other clinical sources. The diagnosticians were trained to high levels of reliability and accuracy (

8). Participants were assigned to receive either four months of weekly group sessions of training in social problem solving (N=38) or an equal amount of supportive group therapy (N=37).

Because the study was conducted with outpatients at a Veterans Affairs (VA) hospital, 90 percent were male. Forty-eight percent were African American, 13 percent Hispanic, 2 percent Asian, and 37 percent Caucasian. The mean±SD age of the sample was 38.7±8.8. More than 85 percent had never been married. The mean number of years of education was 12.3. The mean duration of illness was 13.2±8.9 years. No significant differences were found between the persons assigned to the two treatment conditions on any of the demographic or clinical variables, including chlorpromazine-equivalent dosages of antipsychotic medication. Each group consisted of four to six patients recruited from among stabilized outpatients living in residential care homes or their own apartments.

Interventions

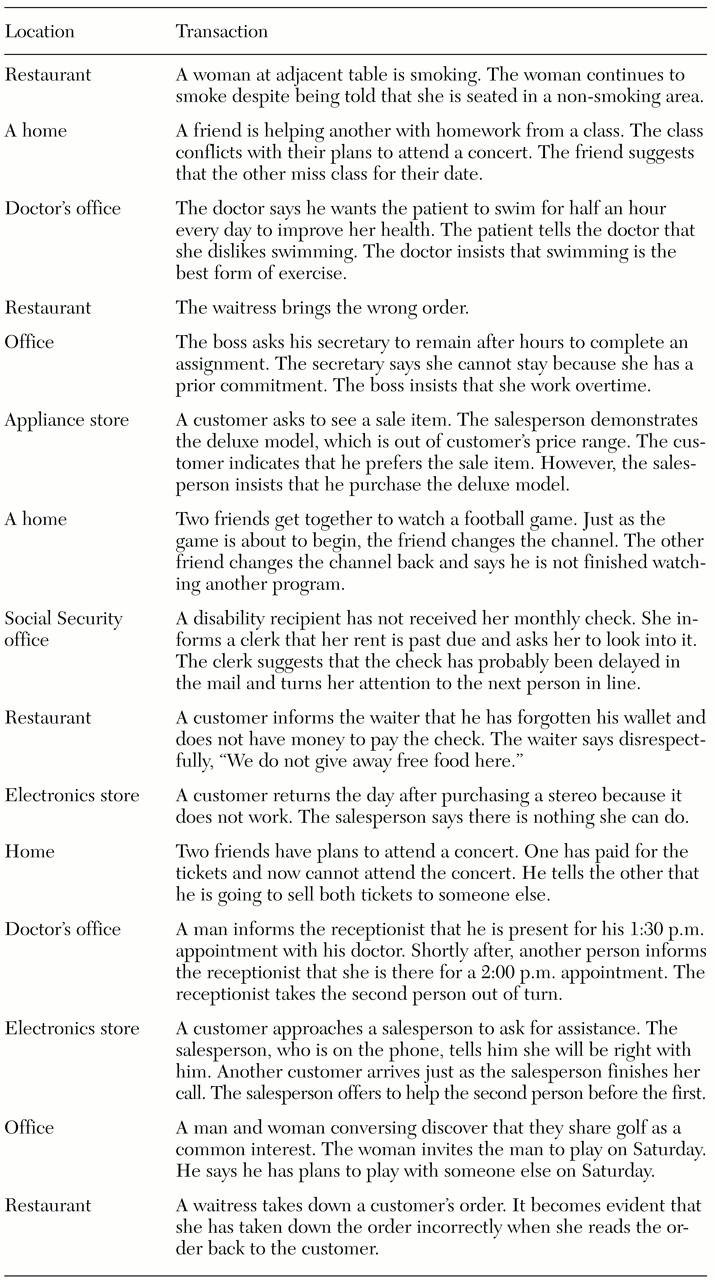

The module consists of a trainer's manual and a videocassette. The manual has step-by-step, prescriptive instructions for the therapist or trainer on how to conduct each group session. The aim of the module is to teach participants how to identify and successfully cope with problems encountered in everyday life. The videocassette demonstrates each step of social problem solving. The steps are identifying the problem, generating alternative solutions, weighing the pros and cons of each alternative, selecting a feasible solution, and planning to implement the selected alternative. The videocassette depicts 15 interpersonal scenes that serve as prompts to evaluate the participant's mastery of the technique (

Table 1).

In a typical session, the trainer might tell the participants: "Let's pretend that you are applying for a job. You arrive on time for the interview but are told by the receptionist that the interviewer has gone home for the day. The problem here is that an obstacle has been thrust in your pathway to achieving your immediate goal, which was the job interview. In learning to do problem solving, the next step is to come up with alternatives that might enable you to remove the obstacle; for example, you might ask the receptionist if there's another person in the office with whom you can interview. Not only is what you say to the receptionist important in determining her response but also how you say it with verbal and nonverbal expressiveness."

Then the trainer shows the group a segment of the videocassette that provides both poor and good examples of coping with social problems. The trainer then uses the manual as a guide to engage the participants in a Socratic dialogue to ensure that they assimilated and comprehended the material on the video. Role playing with coaching and feedback follows until the participants achieve satisfactory ratings of their problem-solving skills.

In the comparison group, participants were led in an open-ended discussion of the problems they were experiencing in their lives, but no structured method was presented for coping. Instead the therapist, an experienced doctoral-level psychologist, encouraged participants to share their ideas for helping each other deal with the problems presented. Informal problem solving was done, but the therapist studiously avoided any structured approach.

Assessment

A psychometrically sound interview and role-play instrument, the Assessment of Interpersonal Problem-Solving Skills (AIPSS), was administered to the participants in both treatment conditions before and after the interventions (

7). The AIPSS consists of 13 videotaped vignettes, ten of which depict a problem between two people. The other three are neutral scenes that do not represent problems.

In administering the test, the rater instructs the subject to take the part of the protagonist in the videotaped scene and to respond to a series of questions that correspond to the problem-solving steps, such as "Was there a problem in that scene?" (identification of a problem), and "Please tell me what you would do or say if you were in that situation" (generating alternatives).

Results

Fifty-three participants completed the two interventions and the pre- and postintervention AIPSS.

The baseline level of accuracy in identifying problems in the scenarios from the AIPSS was very high for participants in both groups. More than 80 percent of the responses were correct in identifying whether a problem existed in the scenes. After the interventions, accuracy of identification increased significantly, to almost 90 percent in both groups (F=8.29, df= 1, 51, p= .006). Patients in both groups also significantly improved in their ability to describe the problems, including the obstacles and goals faced by the protagonists. The range of correct responses rose from 68 to 73 percent before the interventions to 83 to 86 percent afterward (F=25.47, df=1, 51, p<.001).

However, the patients who received the module training demonstrated significantly greater improvements in the other four dimensions of social problem solving than did their counterparts in supportive group therapy. In the generation of alternatives, improvement was 22 percent for module training versus 9 percent for supportive therapy (p<.03). In the selection of an alternative, improvement was 19 percent for module training versus 7 percent for supportive therapy (p<.02). In the quality of the verbal and nonverbal skills of the subject in a role play of the selected solution, improvement was 20 percent versus 6 percent (p<.04). In the overall quality of the role-played performance, improvement was 23 percent versus 6 percent (p<.02).

Discussion and conclusions

In this group of outpatients with schizophrenia, the capacity for identifying and describing common problems involving individuals in everyday life situations was excellent and not different from that shown by persons without mental disorders (

6). This finding is perhaps surprising, because biological and neurocognitive studies of patients with schizophrenia often report that they show substantial deficits in laboratory tests of social perception. More challenging for the patients in this study were aspects of social problem solving that required them to generate solutions and the expressive skills required to put a solution into effect. In these dimensions, structured and systematic training in social problem solving made a significant difference in ameliorating the deficits.

Because the training module included scenarios that were different from those in the assessment instrument, it is possible to conclude that four months of systematic training in social problem solving can yield generalizable outcomes that may be helpful to the patients in many other realms of functioning. In fact, studies have found generalization of skills to a wide array of community activities when this approach to training skills has been used for six months or longer (

3,

4).

We believe that teaching individuals with psychotic disorders social problem solving, especially when such training is done through "overlearning" or "errorless learning," may inoculate them against stress-induced relapse. Moreover, regular use of problem solving in everyday life can enhance social functioning and empower individuals to attain more of their personal goals.

Afterword by the column editors: Some clinicians might argue that teaching persons with schizophrenia a structured mode of social problem solving is artificial and inappropriate because normal people do not go through these stepped progressions. However, many persons with schizophrenia have neurocognitive deficits that make it difficult for them to conceptualize spontaneously and think flexibly when stymied by obstacles. Providing them with an auxiliary method of social problem solving may be just as helpful and constructive, albeit as "artificial," as providing a wheelchair to a person with a spinal cord injury.

Moreover, just as people with severe spinal cord injuries learn how to maneuver their wheelchairs through experience and practice, an individual with schizophrenia must be given the opportunities and coaching to use newly acquired skills in novel situations. The UCLA Social and Independent Living Skills modules were designed to facilitate such learning and have been demonstrated to achieve these ends in a number of randomized controlled trials (

9). However, our society must do for people with schizophrenia what it has done for wheelchair-bound individuals—namely, to recognize the moral imperative to make therapeutic accommodations to the needs of this disabled and highly stigmatized population that enable them to actively and effectively participate in everyday community life.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants MH-30911 to the Intervention Research Center for Treatment and Rehabilitation of Psychosis (Robert Paul Liberman, M.D., principal investigator) and MH-41573 (Stephen R. Marder, M.D., principal investigator) from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors acknowledge the assistance of Sun Hwang, M.S., in statistical analysis. They also thank Karen Blair, Karin Zimmerman, Malca Lebell, and Joanne McKenzie.