The Epidemiologic Catchment Area study (

7) found that about one-third of adults who suffered from a major depressive disorder had not sought treatment. In a review of studies of adult depression, Hirshfeld and associates (

8) found serious undertreatment of persons with depression, even though effective treatments have been available for several decades. They concluded that patient-associated reasons for undertreatment include failure to recognize symptoms, limited access to services, lack of insurance, fear of being stigmatized, and noncompliance with treatment. A further conclusion was that inadequate training of health care providers and barriers created by mental health care delivery systems also contribute to undertreatment. The cost to individuals, families, and society of undertreatment is substantial (

8,

9,

10).

Individual characteristics found to affect child mental health service utilization include the child's age (

18,

19,

20), gender (

18,

20,

21,

22), ethnicity (

19,

20,

21,

23), physical illness (

24), and level of functioning (

17,

25,

26). Family characteristics include socioeconomic status (

19,

22,

24) and the parents' use of mental health services (

22), their perception of the child's need for mental health services and whether the need was met (

17), and their perceived burden (

27). All these factors, with the exception of perceived parental burden, were taken into account in this study.

Most studies of child and adolescent mental health service need and service use have not examined the association between service use and specific psychiatric disorders. Little is known about the factors that affect mental health service use for depression or the types of treatment received by children with depression. In this context, our study addressed three questions: What are the factors associated with receiving professional help for childhood depression? What are the factors associated with receiving antidepressants for depression? Are there shared and unique factors associated with receiving professional help and receiving antidepressants?

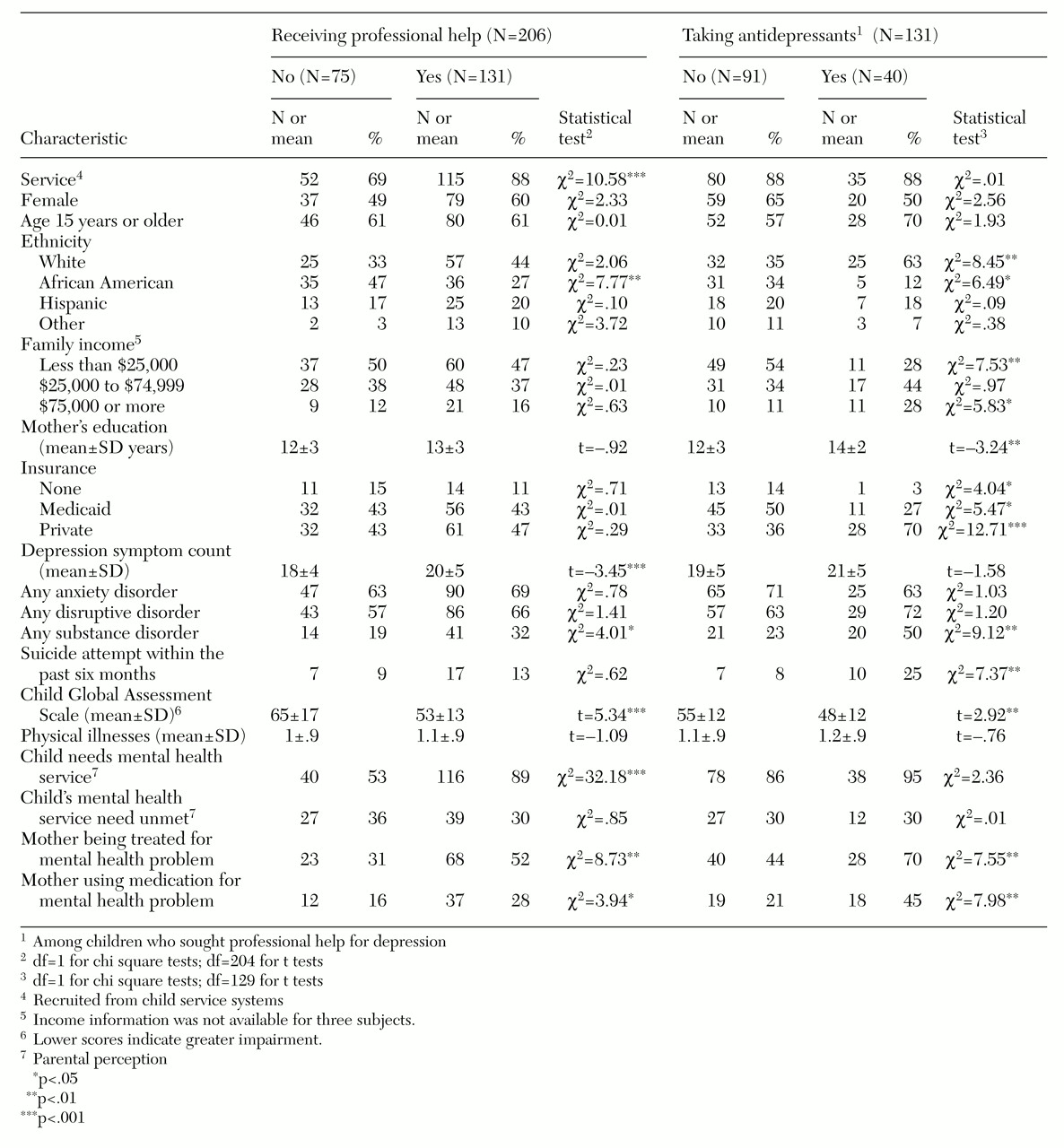

Analysis

We were mainly interested in two binary dependent variables: whether the depressed children had received professional help for depression, and whether those who received professional help received antidepressants. A univariate analysis was first conducted to compare sociodemographic characteristics, other psychiatric disorders, and other factors of depressed children who received professional help with those who never received any professional help for depression. Among those who received professional help, univariate analysis was used to compare those who received antidepressants with those who did not. A chi square test was used for categorical variables, and a t test was used for continuous variables.

Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to identify factors that affected mental health service use for depression among all depressed children. For those who received help, the same method was used to identify the factors differentiating those who were taking antidepressants from those who were not.

The two dependent variables—receipt of professional help and receipt of antidepressants—correspond to the two dichotomies of the service use hierarchy; the comparison for antidepressant treatment was nested within the comparison for getting professional help. Therefore, in the last stage of our analysis, we used a nested response model (

33) to examine whether the factors affecting receipt of professional help for depression were the same as those affecting receipt of antidepressants. The model was tested using the SAS generalized linear models (GENMOD) procedure (

34).

Results

Sample description

Of the 206 depressed children and adolescents, 116 (56 percent) were girls, 82 (40 percent) were white, 71 (35 percent) were African American, 38 (18 percent) were Hispanic, and 15 (7 percent) were other. The mean age±SD was 14.4±2.3 years. Thirty-nine children in the community sample (7.3 percent) and 167 children in the child service systems sample (21.9 percent) were depressed.

Comparisons of demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of depressed children from the community with those from the service systems show that depressed children from the service systems were more likely to be boys, to be ethnic minorities, to be from disadvantaged families with a low income, and to be on Medicaid (data not shown). These notable differences between the children from the community and those from service systems were anticipated. In the subsequent multivariate analyses, a dummy variable—services versus community—was included to control for differences in the community and service systems samples.

Univariate analyses

Of the 206 depressed children, 131 (64 percent) received professional help; 75 (36 percent) did not seek professional help for depressive symptoms.

Table 1 shows the family and individual characteristics of depressed children who received professional help compared with those who did not. African-American youth were less likely to receive professional help than those from other ethnic groups. As expected, depressed children who received professional help were more likely to have a greater number of depressive symptoms and more impairment than those who did not receive such help. Mothers of depressed children who received professional help reported greater use of mental health services and medication for their own psychiatric problems and were more likely to think that their children needed mental health services than mothers of depressed children who did not receive help.

Among the 131 children who received professional help, antidepressants were prescribed for 40 (31 percent) in the year before the interview. As

Table 1 shows, children who received antidepressants were significantly more likely than children who did not to be white, to have a mother who had received professional help and antidepressants, and to be more impaired. Families of children who received antidepressants also had a higher average income and a higher level of maternal education and were more likely to have private insurance. Children who received antidepressants were also more likely to meet criteria for substance abuse disorders and to have recently attempted suicide.

Multivariate Analyses

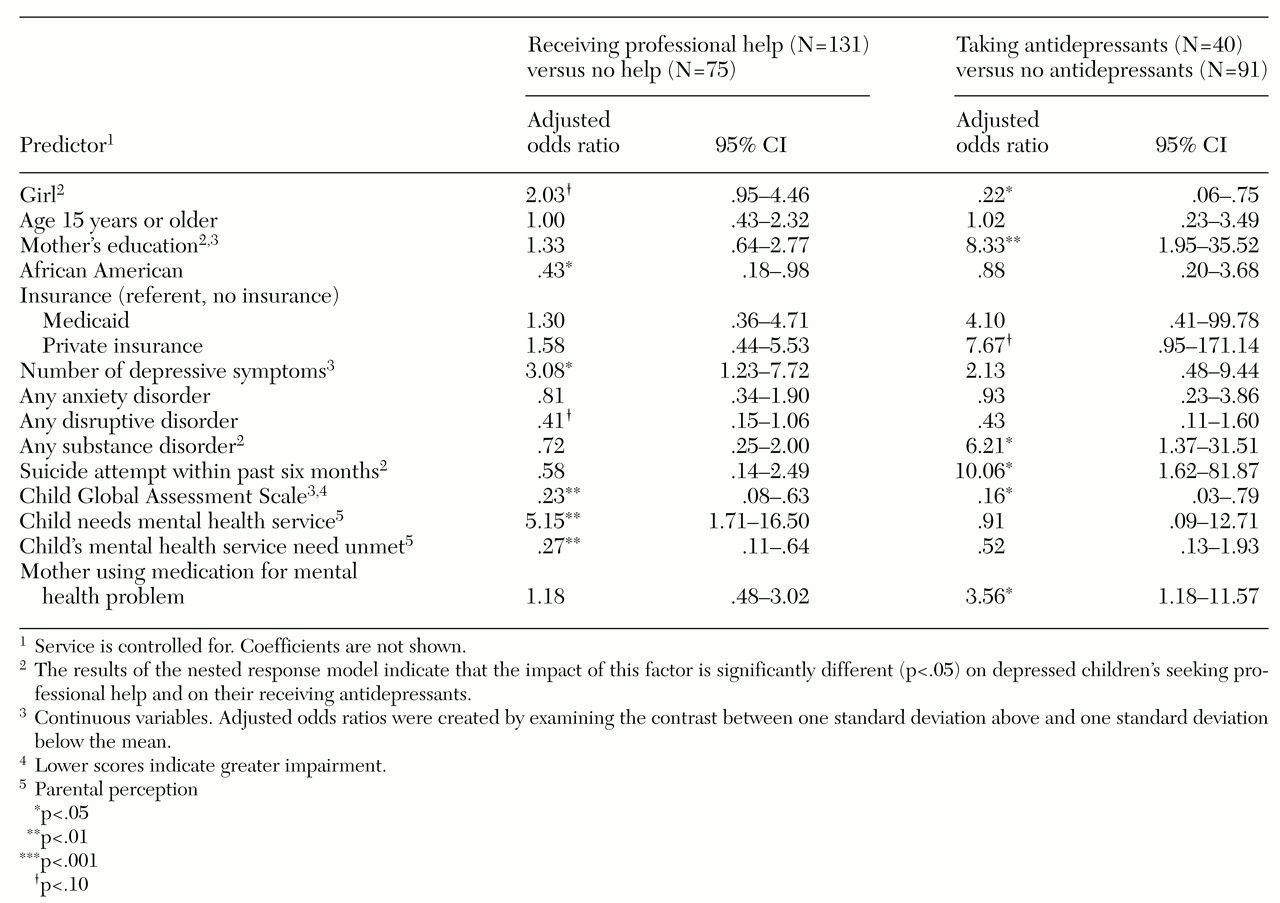

Table 2 shows the results of two logistic regression analyses. Because the results shown in

Table 1 indicated that the major ethnic difference was between African Americans and other ethnic groups, African Americans were compared with all other ethnic groups in the logistic regression analysis.

Table 2 shows the adjusted odds ratios and confidence intervals for the analysis comparing depressed children who received professional help with those who never received any help and for the analysis comparing those who received antidepressants with those who did not.

As shown in

Table 2, children who received professional help for depression were significantly less likely to be African American, had more depressive symptoms, and were more impaired. Their parents were also more likely to report that the child needed mental health services and were less likely to report unmet need. Girls tended to receive professional help more often than boys, and children with disruptive disorders were less likely than other depressed children to receive treatment for depression.

Among children who received professional help, factors significantly associated with receiving antidepressants included being male, a higher level of maternal education, comorbid substance use disorders, a recent suicide attempt, and greater impairment. Children from families with private health insurance tended to receive antidepressants more often than those from families with no insurance.

As discussed above, we were interested in identifying factors that affected whether children received professional help for depression and that influenced whether antidepressant medication was prescribed for those who received help. In addition, we wanted to identify shared and unique factors associated with receiving professional help and antidepressants. Because the comparison of children who received antidepressants was nested within the comparison of children who received professional help, the model of nested responses (

33) was applied to the data.

We identified four factors with differential impact on the receipt of professional help for childhood depression compared with the use of antidepressants among those receiving professional help. Girls were more likely to receive professional help for depression; however, among all those who received help, boys were more likely to receive antidepressants (p<.01). Also, the mother's education and the child's comorbid substance use disorders and previous suicide attempt were significantly related to antidepressant treatment (p<.05) but not to receiving professional help for depression.

Discussion and conclusions

Most studies of child mental health service use have not examined service use in terms of a specific disorder. The study reported here assessed child mental health service use for depression and compared factors affecting the use of professional help and treatment with antidepressants for childhood depression.

Consistent with findings of studies of adults (

7,

8), depression appears to be undertreated among children and adolescents, especially among African Americans (

21,

35,

36). However, it has been suggested that African-American youth more frequently seek help for psychological symptoms from nonprofessional domains such as church and family before seeking formal mental health services than do whites (

37). Further research in this area is needed.

After the analysis controlled for other possible confounding factors, depressed girls appeared to be somewhat more likely to receive professional help for depression than boys. This gender difference is consistent with that found among adults (

38,

39). However, among children who received professional help for depression, boys were more likely to receive antidepressants. These findings suggest that the gender effect may differ by types of service and treatment. More studies are needed to replicate these findings.

Family socioeconomic characteristics did not appear to be significant factors in whether children received professional help, but they did play an important role in whether antidepressants were prescribed. Children who received antidepressants were more likely to come from families of higher socioeconomic status. Although the association with income disappeared in the multivariate analyses, the mother's education remained a significant predictor, suggesting that parental knowledge of depression and of available medications for treatment may influence the type of services received.

Like other studies (

40,

41), our findings did not show a correlation between having insurance and receiving professional help for depression. However, among children receiving such help, those with private insurance tended to be somewhat more likely to receive antidepressants than those with no insurance. These findings suggest that studies examining mental health service use without simultaneously exploring the type of treatment received may not reveal— and may consequently underestimate—the impact of having health insurance. The impact of insurance on different types of treatment for depression and possibly other disorders should be explored.

Consistent with previous studies (

26,

40), our results indicate that level of impairment and severity of depression (number of depressive symptoms) were related to receiving mental health services. The occurrence of other disorders did not appear to be related to a child's receiving professional help for depression. However, among children who received such help, those who received antidepressants were more likely to have a comorbid substance use disorder and to have had a previous suicide attempt. This finding is consistent with previous studies (

1) and suggests that children with depression are more likely to receive antidepressants if they have some life-threatening or severe symptoms, such as a suicide attempt and drug abuse.

In summary, our findings suggest that parental failure to recognize depressive symptoms, lack of knowledge about depression and its related treatment, and lack of adequate health insurance may all influence whether or not a child receives services as well as the type of treatment received. Mental health education should be offered to parents to improve early identification and treatment of depressed children and adolescents.

A limitation of this study is that the information on treatment for depression was limited, as we did not have a measure of psychotherapy. Consequently, the children who did not receive antidepressant treatment could have received anything from a single evaluation to a full range of treatment without antidepressants. It is also possible that some depressed children who received antidepressants had previously received another type of treatment. Therefore, we do not mean to imply that children who received antidepressants got better service than those who did not.

In fact, the literature indicates that although both psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy have been found to be beneficial for depressive disorders, children do not seem to respond to antidepressants as well as adults do (

1,

42,

43,

44,

45). Psychotherapy has been recommended as the first treatment for most depressed youth, with antidepressants considered only for those with more severe depression, bipolar disorder, and depression with psychotic features and those who do not respond to psychotherapeutic intervention (

1). Future research, including detailed treatment information, is needed.

Finally, because of the low prevalence of depression, data from our community and service systems samples were combined to increase the power of the analysis. Although sample differences were statistically controlled and detailed analyses were conducted to ensure that our findings were not due to sample differences, a large-scale study is needed to replicate these findings.