Approximately half of all individuals with severe mental illness have a co-occurring substance use disorder. Compared with individuals who have a diagnosis of severe mental illness only, those with dual disorders experience more difficulties in the community, which often results in homelessness and hospitalization. Integrated outpatient treatment, in which dual diagnosis patients receive treatment for both mental illness and substance abuse, results in high rates of engagement, reduced institutionalization, and remission of substance abuse for many patients (

1).

For individuals with a dual diagnosis who do not respond to outpatient treatment, residential treatment provides intensive services combined with safe housing and assistance with daily living, and it is less expensive than inpatient treatment. However, studies of residential programs for dual diagnosis patients, including our own study, have found poor patient retention and only modest improvements in substance abuse and hospitalization rates (

2,

3,

4,

5). One reason for these poor outcomes may be that the duration of treatment was too brief for the patients to consolidate gains.

To address the problems associated with our existing short-term program, we instituted a long-term residential treatment program for adults with dual diagnoses. Both our short-term and long-term programs provided integrated substance abuse and mental illness treatment in a day program setting. The short-term program was eventually closed because of poor outcomes.

The long-term program differed from the short-term program in several respects. It was community based rather than hospital based. Patients were allowed to enter, leave, and reenter the program over several months while individualized treatment planning occurred. Abstinence was required, but relapse was dealt with therapeutically and did not result in immediate discharge from the residence. Living and vocational skills were emphasized. The patients' length of stay was unlimited, although the goal was to achieve discharge by two years, compared with three to six months for the short-term program.

The purpose of this study was to compare the effectiveness of a long-term residential treatment program for dual diagnosis patients with that of a short-term treatment program. We hypothesized that patients in a long-term program would be more likely to become engaged in treatment, to reduce substance abuse, and to avoid institutionalization in a hospital or jail after discharge. We also hypothesized that patients in the long-term program would show improvement on these measures of adjustment between admission and discharge.

Methods

Study samples

The long-term group comprised 43 individuals who entered the long-term program between 1992 and 1996. They had all failed at attempts at outpatient treatment. A total of 56 patients entered the program during this period. At six-month follow-up, six of the patients remained in the program, and seven had moved; these 13 patients were not included in the analyses. The overall demographic characteristics of the 56 patients in the long-term admission group were similar to those of the 43 individuals in the follow-up group.

Thirty-eight (88 percent) of the patients in the long-term group were Caucasian, 30 (70 percent) were men, 17 (44 percent) had at least a high school education or equivalent, and 15 (35 percent) had ever been married. The mean±SD age was 36±7 years. Twenty-seven patients (63 percent) were diagnosed as having a schizophrenia spectrum disorder, 14 (32 percent) of having an alcohol-use-only disorder, five (12 percent) of having a drug-use-only disorder, and 24 (56 percent) of having both an alcohol and a drug use disorder. The mean±SD length of stay was 400±496 days.

The short-term group comprised 39 of the 41 adults with dual disorders who entered the short-term residential program between 1990 and 1991 (

5). The patients' mean±SD length of stay was 66±56 days.

Chi square tests and t tests were used to compare demographic and diagnostic characteristics of the short-term group with those of the long-term group. The groups were similar on all characteristics except two. More individuals in the short-term group had at least a high school education or equivalent (31, or 78 percent, versus 24, or 47 percent). Also, more individuals in the short-term group had a diagnosis of alcohol-use-only disorder (17, or 42 percent, versus 17, or 30 percent).

Measures

On admission to the long-term program, patients were given a structured interview that included the Time-Line Follow-Back (

6) to assess alcohol and drug use; the medical, legal, and substance use sections of the Addiction Severity Index (

7); a detailed chronological assessment of housing and institutional stays using a self-report calendar (

8); and the Service Utilization Interview (

9).

Patients were rated on the 5-point Alcohol Use Scale and Drug Use Scale (

10) at admission and at follow-up. Additional follow-up data were drawn from the patients' State Mental Health Statistics Improvement Project forms. To find missing data, the first author reviewed clinical records.

Patients admitted to the short-term residential program were also given a structured interview, which was conducted by a research psychiatrist who used methods similar to those used with the long-term patients (

5).

Treatment engagement was defined as a stay of at least three months.

Results

Short-term versus long-term outcomes

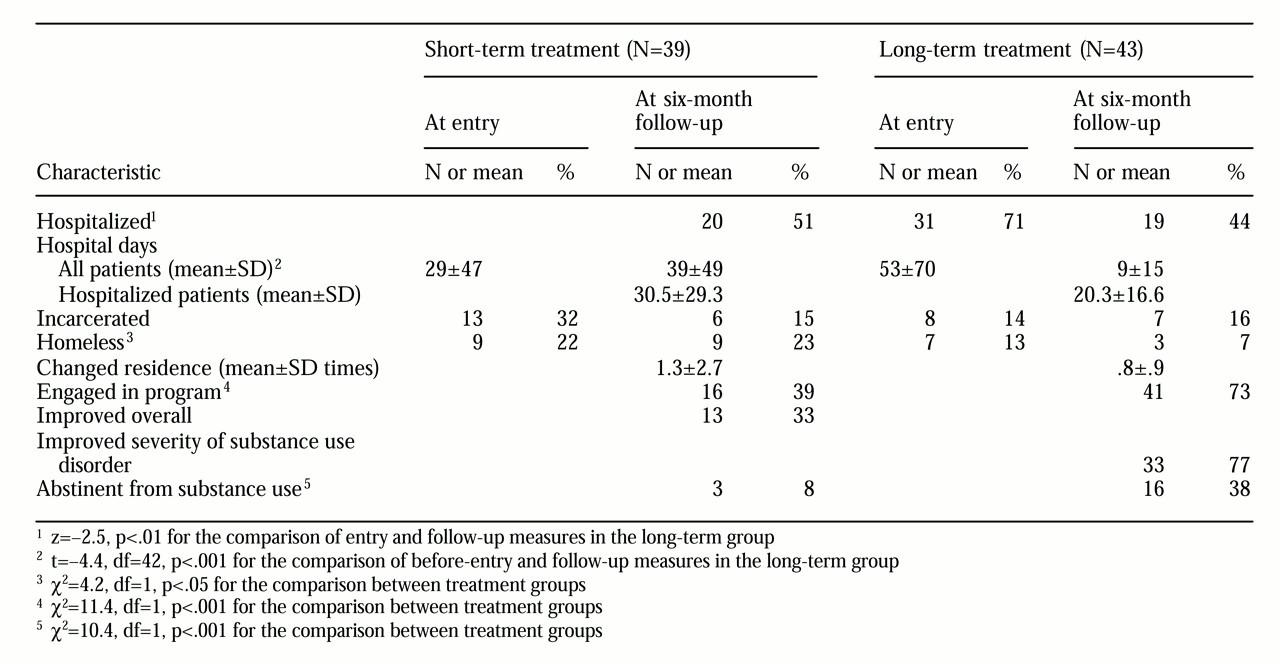

Table 1 shows the comparison for engagement and six-month outcomes between the short-term group and the long-term group. Patients in the long-term program were significantly more likely to become engaged in treatment, and after discharge they were more likely to maintain abstinence and less likely to experience homelessness. No statistically significant differences were found between the two groups at follow-up for measures of incarceration, psychiatric hospitalization, or number of moves.

Changes within the long-term group

Substance abuse outcomes were not analyzed for three patients who were in a controlled environment at follow-up. Of the 40 remaining patients, 20 (50 percent) had maintained remission from all substance use disorders, and 16 (38 percent) had maintained complete abstinence from substance use at six months after discharge. The severity of the substance use disorder had lessened for more than three-quarters of the patients. The mean length of stay in the long-term program was 624.9±578 days for the 20 patients in full remission from substance use disorders, compared with 165±228.2 days for the 20 patients who still had an active substance use disorder (t=3.5, df=1, p=.002). Psychiatric hospital use was also significantly less among patients in the long-term group at follow-up. No statistically significant changes in homelessness, housing instability, and incarceration were found.

Discussion and conclusions

The results of our study support the effectiveness of long-term residential treatment for individuals with dual disorders who have not responded to outpatient treatment. Overall, patients in the long-term program had significantly better outcomes than those in the short-term program. In addition, patients in the long-term program who achieved full remission of their substance use disorder had stayed in the program longer.

Treatment duration and flexibility appear to be critical features of successful treatment. Longer stays may have resulted in better outcomes because patients were provided with a safe, sober, stable living environment in which they could take time to learn the skills necessary to maintain abstinence. In addition, longer stays allowed more flexibility in engagement, social and vocational rehabilitation, and transition back to the community.

This study was limited by the nonequivalence of study groups and time periods, small group sizes, and potential regression to the mean. Results may not be generalizable because of circumstances particular to small cities in New Hampshire.

Further research is needed to confirm the effectiveness of treatment and the cost-effectiveness of long-term residential treatment for this population.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant R24-MH-56147 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors thank Brenda LaPointe, R.N., of the Mental Health Center of Greater Manchester.