Cocaine abuse and dependence are common among persons who have schizophrenia, and prevalence rates vary by setting. Studies have estimated that 16 to 40 percent of persons who have schizophrenia abuse cocaine, and rates are as high as 70 percent in some hospital emergency services, inpatient units, and outreach programs (

1,

2).

The high rates are of particular concern because cocaine use by persons who have schizophrenia leads to increases in the severity of positive symptoms, treatment noncompliance, violence, HIV infection and other medical problems, housing instability, homelessness, and higher health care costs (

3,

4). In general, when a person who has schizophrenia is abusing cocaine, treatment is more challenging. However, some patients respond well to addiction treatment that involves focused interventions. Others require extensive treatment that integrates addiction and mental health treatment.

A variety of hypotheses have been proposed to explain why persons who have schizophrenia abuse cocaine. They include greater dysregulation in the dopamine system, a desire to reduce negative symptoms or the unwanted side effects of conventional neuroleptic medications, limited social and community support, and social isolation (

5). In addition, deinstitutionalization has resulted in increased substance use because of easier access to drugs (

5).

Neuroimaging studies suggest that aberrations in the dopamine system play a role both in schizophrenia and in maintaining cocaine addiction via craving. Craving is a manifestation of internal affective and motivational processes that can persist for three to 12 months after last use, although the intensity of craving is highest during the first three months of abstinence or in response to specific triggers (

6).

Few studies have directly examined craving in individuals who have cocaine dependence and schizophrenia, although several medication trials in this population have used craving as a secondary outcome measure. Our clinical experience indicates that among cocaine-dependent persons, those who have schizophrenia complain more about high-intensity and persistent cocaine craving than those who do not have schizophrenia. Therefore, we undertook this study to evaluate whether individuals who have schizophrenia and cocaine dependence experience more intense craving than cocaine addicts who do not have schizophrenia. We were also interested in using a repeated-measures design to examine the stability of craving during the first few days of abstinence from cocaine.

Methods

We compared cocaine craving in two groups: 20 cocaine-dependent male outpatients who had schizophrenia and who were participating in a chemical abuse program for persons with mental illness and 20 cocaine-dependent men who did not have schizophrenia and who were recruited from the substance abuse outpatient treatment program at the Veterans Affairs New Jersey Health Care System. The study was conducted in 1998 and 1999.

To be included in the study, participants had to meet DSM-IV criteria for cocaine dependence, to report having used at least six grams of cocaine a month, and to have been abstinent from cocaine for two weeks at the time of the study. The patients met DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia. Diagnoses of schizophrenia and cocaine dependence were made independently by a doctoral-level psychologist. Persons were excluded who had a history of dependence on opiates, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, marijuana, or alcohol; who met DSM-IV criteria for another current axis I disorder; and who had been abstinent from cocaine for more than two months. Persons were excluded from the comparison group if they were currently taking prescribed medication that could affect the central nervous system; patients who had schizophrenia were not excluded for this reason. Institutional review board approval was obtained for this study.

After giving written informed consent, participants completed a demographic survey and the Voris Cocaine Craving Questionnaire (VCCQ), a four-item, self-report, 50-point visual analogue scale (

7). The VCCQ was chosen because of its good reliability and validity when used with cocaine-dependent persons who do not have schizophrenia (

7) and because most psychiatric patients find it easy to complete. The four items on the scale include craving intensity, measured along a scale from craving to no craving; mood, happy to sad; energy, too little to too much; and feeling, good to bad. The intensity item measures a person's craving state, and the other three items measure subcomponents of that state. Respondents score each item by marking a line through a 50-point scale that reflects their current state. To examine craving stability, we administered the VCCQ at baseline and 72 hours later.

Student's t test was used to examine group differences in cocaine craving, and Pearson's correlation coefficient was used to examine craving stability.

Results

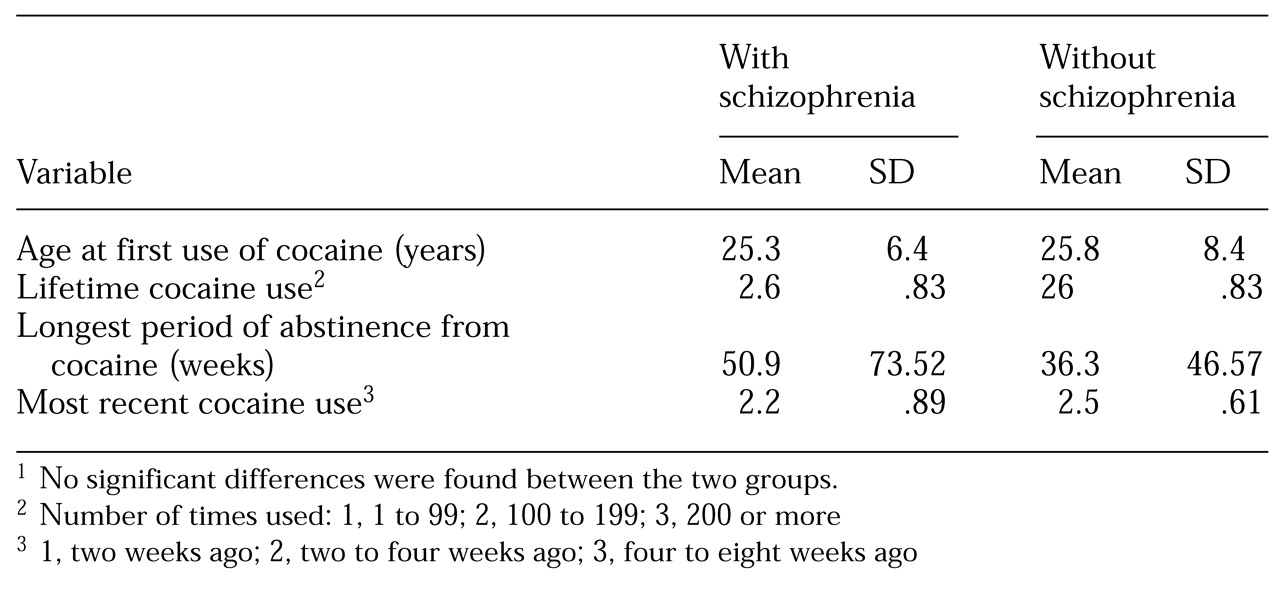

No significant differences were found in sociodemographic characteristics or in the frequency, intensity, or duration of substance use between cocaine-dependent persons who had schizophrenia and those who did not. The mean±SD age of patients in the schizophrenia group was 25.3±6.4 years. Eighteen (90 percent) of the patients in this group were African American, one (5 percent) was Hispanic, and one was white. The mean±SD age of patients in the group without schizophrenia was 25.8±8.4 years. Fifteen (75 percent) were African American, four (20 percent) were Hispanic, and one (5 percent) was white.

Table 1 summarizes data about cocaine use in the two groups. However, as shown in

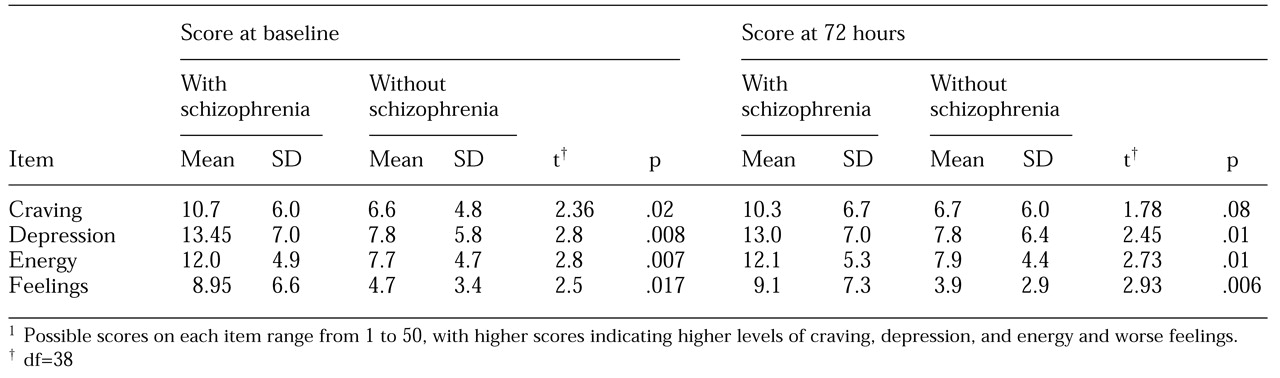

Table 2, persons in the schizophrenia group reported a significantly higher level of craving, depression, and energy and felt worse than those in the comparison group.

Craving stability over the 72-hour period was high in both groups on three of the four items—depression (Pearson's correlation coefficient= .73), energy (.64), and feeling (.68). In both groups, the intensity of craving was slightly less stable (.53).

Discussion

The findings support our hypothesis that during early abstinence, cocaine-dependent persons who have schizophrenia experience more intense cocaine craving than cocaine-dependent persons who do not have schizophrenia. We also found that the intensity of cocaine craving remained stable over a 72-hour period in both groups.

Cocaine-dependent persons who have schizophrenia may be particularly vulnerable to relapses and may require specialized psychosocial and pharmacological interventions to manage their craving and to reduce relapses. The persistently high level of craving noted in this study may partly account for the poorer retention in outpatient treatment and recurrent hospitalizations in this population (

8). These patients also appear to be particularly vulnerable to the instability that frequently accompanies the transition from inpatient to outpatient treatment (

9). A higher level of cocaine craving may be related to having a neurobiological vulnerability and more psychosocial instability.

These preliminary results should be interpreted with caution given the small sample and lack of a structured interview to maximize diagnostic certainty. Furthermore, the study relied on a self-reported measure of craving. Laboratory exposure to drug cues, such as videotapes of cocaine and of people using it, would have helped determine group differences in craving in a controlled setting (

10). Such exposure provides an opportunity to examine an individual's triggers for cocaine use and to monitor the intensity of response.

Because persons who have schizophrenia may use cocaine to manage or self-medicate their negative symptoms and the extrapyramidal side effects of medication, future investigations should include negative symptoms and side effects as dependent variables. It is interesting that preliminary reports suggest that atypical neuroleptics, which are thought to produce fewer extrapyramidal symptoms and negative symptoms and to reduce dopamine transmission during acute withdrawal, have been shown to reduce craving among persons who have schizophrenia and cocaine dependence (

11).

The relationship between cocaine craving and relapse to both drug use and psychiatric illness supports continued efforts to evaluate medications and psychosocial treatment approaches. Several naturalistic and open pilot pharmacotherapy studies suggest that patients taking the atypical agents clozapine, olanzapine, and risperidone have better treatment outcomes, including treatment for cocaine addiction, than those taking conventional neuroleptics (

11,

12,

13). Psychosocial treatments have also been developed that blend and modify the best psychosocial approaches in mental health treatment—social skills training, case management, and outreach—and the best psychosocial approaches in addiction treatment—relapse prevention, cognitive-behavioral therapy, motivational enhancement therapy, and 12-step recovery programs. Clinical experience and research support the integration of mental health and addiction treatments, pharmacotherapy, and psychosocial treatments to best treat cocaine addiction (

14).

We and others are currently conducting double-blind studies to integrate psychosocial and pharmacological interventions and to determine whether use of conventional or atypical neuroleptics is associated with less intense cocaine craving and fewer relapses among persons who have schizophrenia and cocaine dependence.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Aron Starosta, M.D., for helpful comments.