Procedure

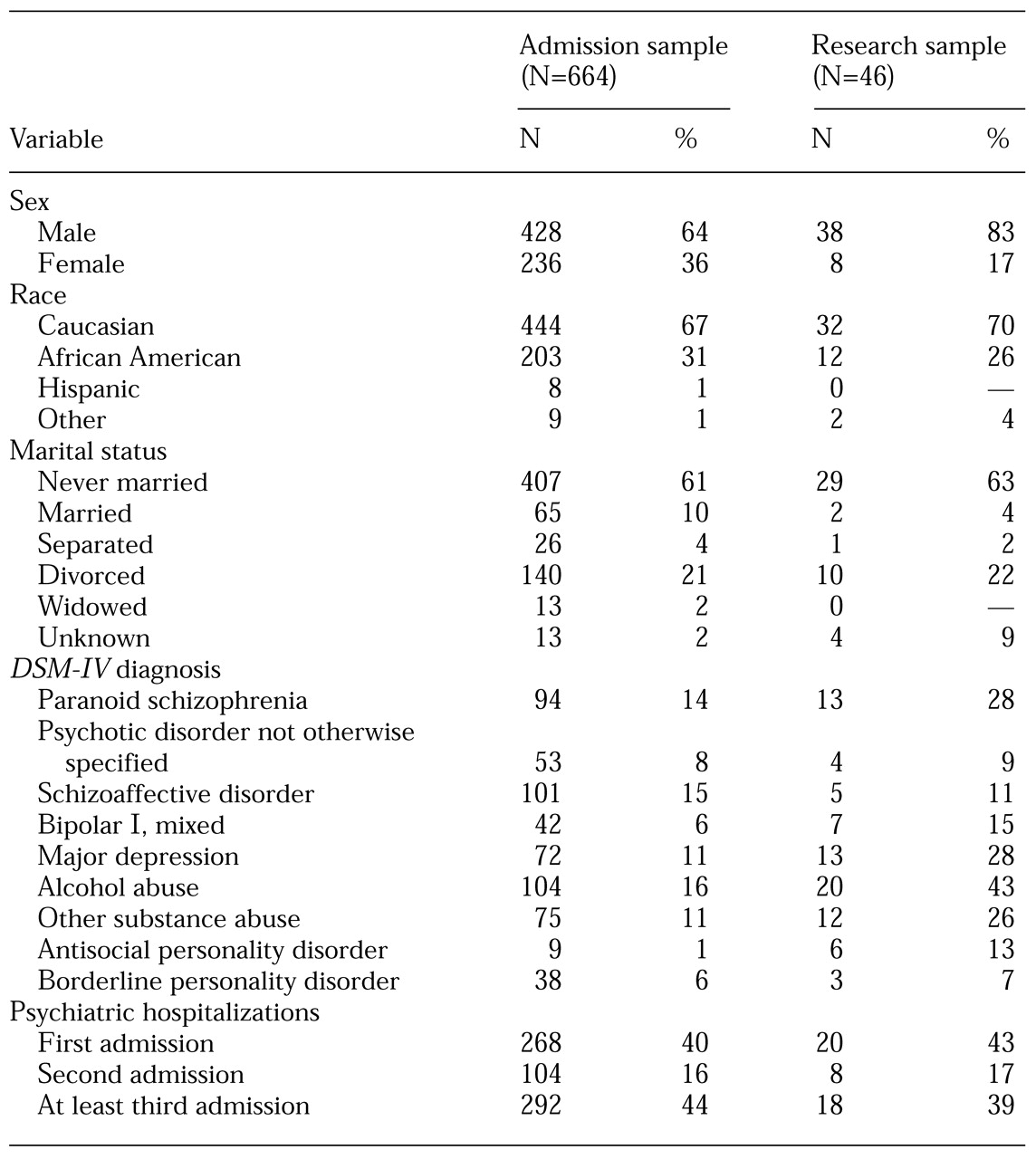

Assessment. All patients were assessed by a psychiatrist on admission. Psychiatrists used a checklist of risk factors to record each patient's psychiatric symptoms and DSM-IV diagnoses as well as specific information on history of violence, crime, and psychosocial stressors as indicated by information obtained from a mental status examination, behavioral observations by staff, and collateral resources.

This information was then passed on to a multidisciplinary treatment team, who reviewed the information within 24 hours of the patient's admission. The multidisciplinary team— typically composed of the patient's attending psychiatrist, a registered nurse, a psychologist, a social worker, the patient's case manager, various ancillary therapists, and the patient—determined the patient's risk-related needs and gathered more detailed information about the patient's history of threatening to harm him- or herself or others with a firearm and the patient's access to firearms.

For patients who were identified as having threatened to harm themselves or others with a firearm or as having access to a firearm, the multidisciplinary treatment team implemented a treatment plan that included measures to immediately address the risk posed to the patient or to others—for example, notifying family members of threats or referring the patient to a firearms treatment group. During the next 72 hours, a more comprehensive treatment plan was implemented, which addressed issues beyond the risk of harm posed by the patient—for example, substance abuse and lack of housing.

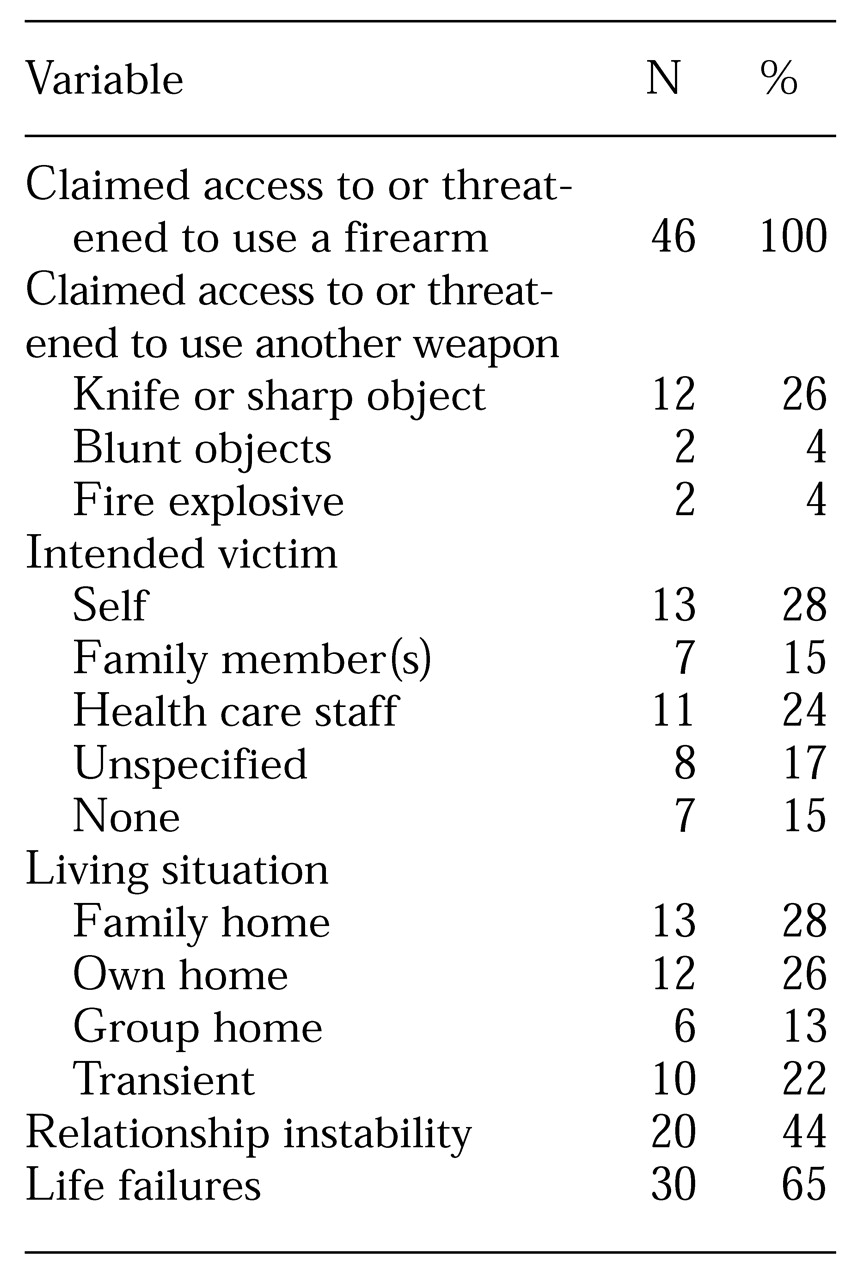

Throughout treatment, patients who were identified as having threatened themselves or others with a firearm or as having access to a firearm were further assessed by an assigned social worker. The social worker completed a firearms flow sheet, which documented the type and location of the firearm and any identified victim and that victim's awareness of the threat. The social worker then contacted the patient's family, the patient's case manager, and law enforcement officials, as necessary, to verify the patient's access to a firearm and any firearm-related threats.

If family members minimized the issue of the patient's access to a firearm or threats to use a firearm, the social worker explained the potential associated risks. In addition, the social worker strongly encouraged the families of patients who had access to a firearm to restrict that access—for example, to remove the firearm from the home. Information gathered from collateral sources and the steps taken by the social worker to neutralize the risk of the patient's using the firearm were then documented on the firearms flow sheet.

Monitoring. Each patient's treatment plan was subjected to a quality assurance process to determine whether all the identified risk-related needs were being adequately addressed. Risk-related needs that were identified as not being adequately addressed were referred back to the multidisciplinary treatment team. A follow-up review occurred within 48 hours to ensure that the indicated corrections or additions had been made.

Treatment. A therapy group on self-control skills for interpersonal stressors was specifically designed for patients who were identified as having threatened to harm themselves or others with a firearm or as having access to a firearm. Staff members from the psychology and social work departments facilitated this group. In the therapy group, patients learned to identify how they had relied on external physical means—firearms in particular—to deal with their psychiatric, psychological, and emotional problems.

Members of the group specifically learned to distinguish between internal and external coping skills and then to identify and begin using alternative and socially appropriate methods to gain control. They learned not to rely on or to use firearms or other weapons. The facilitator taught basic cognitive-behavioral concepts, including understanding the relationship between thoughts, feelings, physiology, and behavior and the relationship between antecedents, behaviors, and consequences. The patients were trained in behavioral time-outs, relaxation techniques, and stress management exercises. Treatment goals focused on effective and assertive communication, problem solving, and conflict resolution without the use of force or threats.

Consultation. Consultation was available to address diagnostic issues or interventions at any point during a patient's assessment or treatment. Consultations were requested by the patient's multidisciplinary treatment team and included professionals such as forensic psychiatrists, psychopharmacologic experts, and the medical services director.

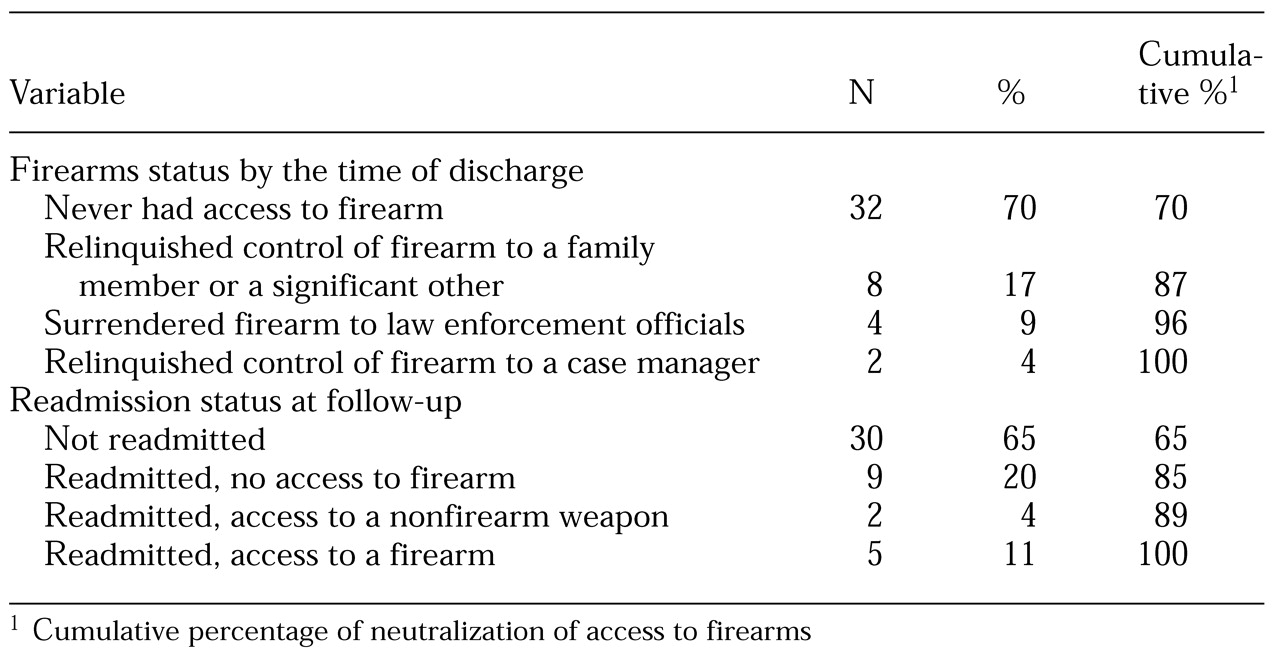

Discharge. After a patient had been stabilized, the priority of treatment was to discharge the patient to the least restrictive, safest environment available, while maintaining neutralization of the risk of firearms use. To this end, the treatment team developed a detailed relapse prevention plan for identifying symptomatic and behavioral cues related to risk and for activating outpatient assessment on the emergence of any of the identified cues. Twenty-four hours before discharge, the patient's social worker forwarded the firearms flow sheet to the social work supervisor, who reviewed the flow sheet and the medical record to determine whether there were any outstanding risk issues and, if so, how these issues should be addressed. The discharge plan and related information were then forwarded to the community discharge agency.

After the patient's discharge, the community discharge agency was responsible for continually monitoring whether the patient had regained access to a firearm. If the patient had regained access, appropriate actions could have included—but would not necessarily have been limited to—protecting the patient from self-harm and notifying potential victims of the possible danger.