For patients with chronic mental illness, the introduction of atypical antipsychotics has opened new possibilities for reintegration through meaningful work and community living. However, the likelihood of patients' sustaining such improvements may depend on their adherence to prescribed medications for months or years in an unsupervised community setting.

Treatment guidelines suggest a year of antipsychotic therapy for patients who are experiencing their first psychotic episode and at least five years of maintenance therapy—if not indefinite therapy—with antipsychotics for patients who have experienced multiple episodes (

1). Yet the psychiatric literature reveals little about the duration and variation of adherence to antipsychotic medication under conditions of routine outpatient care.

This study examined the medication adherence of patients in the community who obtained their initial prescription for an antipsychotic medication at a national retail pharmacy chain. Our first goal was to document the pattern of nonadherence over an eight-month period. Our second goal was to compare differences in adherence for atypical and conventional agents and among individual agents.

Methods

The database for this study consisted of all refill records from a national pharmacy chain from September 1998 through May 1999 for the selected agents. Patients who received a new prescription for a noninjectable form of an agent were included in the study, resulting in an analysis sample of 25,301 patients. The generic and brand formulations of each agent were analyzed. Because some patients received a prescription for more than one antipsychotic, a total of 26,447 courses of therapy were analyzed.

Of the 17,067 initial prescriptions for atypical agents in our database, 290 were for clozapine, 8,785 for risperidone, 1,662 for quetiapine, and 6,330 for olanzepine. Of the 9,380 initial prescriptions for conventional agents, 4,481 were for haloperidol, 1,211 for trifluoperazine, 1,623 for thiothixene, 829 for fluphenazine, and 1,236 for perphenazine. Overall, fewer than 5 percent of the patients switched to another antipsychotic during the study period.

The endpoint of the analysis was medication persistence, that is, the proportion of patients who continued with therapy. Medication persistence was defined as a patient's having a supply of medication in hand at a particular point in time. Treatment persistence was evaluated for each patient at 30-day intervals from the patient's starting date for an eight-month period or until the end of the study period. Because patients who entered the study in later months had less time during which they were at risk of discontinuing therapy, the denominators used for evaluating persistence decreased with each successive month.

By this method, patients were considered to be continuing medication therapy at the end of a given month if they had sufficient medication from a previously purchased refill to carry them past the end of that month or if they subsequently purchased another refill. For example, if a patient purchased an initial prescription and returned for the next refill during month 8 of therapy, he or she was still classified as continuing therapy for the entire eight-month period. Thus patients classified as continuing therapy after eight months could have obtained as little as two months' worth of medication. Persistence, as defined here, simply reflects a patient's tendency to continue with therapy; it does not reflect whether a patient actually took the medication, nor does it measure the clinical benefit received.

Chi square analyses were used for comparisons between groups.

Results

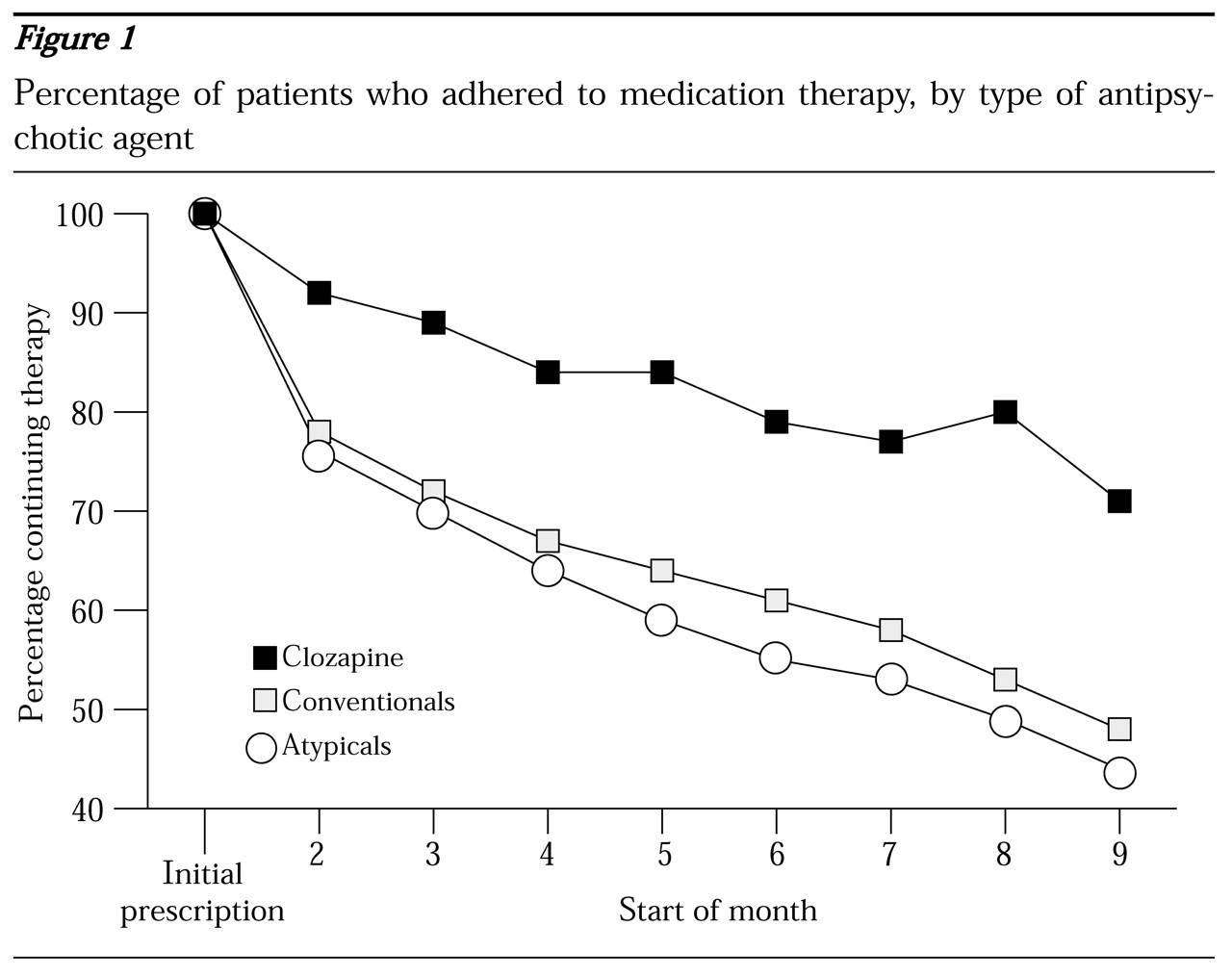

As shown in

Figure 1, persistence with therapy was greater among patients who were taking conventional agents than among patients who were taking atypical agents. At the start of the third month, 72 percent of those taking conventional agents (6,258 of 8,729 patients) were persistent in therapy compared with 70 percent of those taking atypical agents (10,279 of 14,763) (χ

2=11.27, df=1, p<.001). At the start of the sixth month, the respective rates were 61 percent (3,684 of 6,074) and 55 percent (5,466 of 9,922) (χ

2=47.77, df=1, p<.001). At the start of the ninth month, the rates were 48 percent (820 of 1,723) and 44 percent (1,242 of 2,823) (χ

2=5.58, df=1, p<.02). Persistence rates were compared for the different drugs within the group taking conventional agents and the group taking atypical agents. Within-group rates were similar for the drugs in each group.

Patients who were taking clozapine were significantly more likely to continue medication therapy than patients who were taking conventional agents and patients who were taking atypicals other than clozapine (

Figure 1). Of the patients who were taking an atypical agent, 71 percent of those who were taking clozapine (81 out of 114 patients) persisted with therapy at the start of the ninth month, compared with 40 percent of those who were taking risperidone (519 of 1,473) (χ

2=41.37, df=1, p<.001), 40 percent of those who were taking olanzepine (413 of 1,026) (χ

2=39.76, df=1, p<.001), and 33 percent of those who were taking quetiapine (79 of 242) (χ

2=46.98, df=1, p<.001).

Discussion

Our analysis of pharmacy refill records did not show higher levels of medication adherence for atypical agents as a class than for conventional agents. This finding runs counter to the presumed relationship between the improved side effect profile of atypical agents and long-term adherence (

2). Notably, the risk of patients' discontinuing medication was not uniform across points in therapy.

Our data also suggest a risk profile for discontinuation of antipsychotic medication that is greatest at the start of therapy for all agents. Improved follow-up of patients during the first 30 to 45 days of therapy or after discharge from inpatient care may help reduce the risk of discontinuation.

The high and sustained rate of medication adherence in this study among patients taking clozapine differs from rates found in studies that have suggested that poor medication adherence among patients taking antipsychotics is the almost unavoidable norm (

3). Clozapine was unique among the agents we studied in that patients who were treated with this antipsychotic were required to participate in a highly structured medication administration and tracking process. To receive clozapine, patients were required to make at least eight visits a month to the pharmacy and laboratory during the first six months of therapy. Additional contacts with a psychiatrist would also have been made.

Moreover, this process demanded heightened accountability on the part of psychiatrists and pharmacists, who were responsible for certifying weekly or bimonthly white blood cell counts and reporting results of blood tests to a registry for four weeks after a patient discontinued clozapine. This process may have resulted in better patient engagement in therapy and better identification of patients who missed scheduled blood draws or medication. However, a selection bias for more compliant patients or for patients who have better social or systems support may have contributed to the high level of persistence demonstrated by patients taking clozapine.

The extent of poor adherence among patients taking antipsychotic medication observed in this study is similar to that in previous reports. Cramer and Rosenheck (

4) found that the adherence of patients taking medications for psychosis and mood disorders differed little from that of patients taking medication for physical disorders. Teaching patients to use a "feedback" method that links daily activities with the process of taking medication is one approach that can be used to increase rates of adherence (

5,

6). Other methods of increasing adherence, such as mailing reminders to patients at strategic points in therapy, are also being investigated.

A limitation of our study is the lack of collateral diagnostic information. Persistence with atypical agents was likely underestimated in our data set, because for some patients short-term use of atypical agents may have been legitimate; for example, atypical antipsychotics are used for affective disorders and dementia. In addition, some limitations are associated with a pharmacy database; for example, pharmacists may have entered incorrect information into the system or patients may have changed residence, obtained medication refills through other pharmacy chains, or been rehospitalized.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that the improved side effect profile of atypical agents may not automatically ensure high levels of persistence with medication therapy, as is commonly assumed. The high rate of persistence among patients taking clozapine suggests that premature medication discontinuation may be not just a patient issue, but a larger systems issue that may be responsive to processes that improve medication administration and patient tracking. Given the human and financial costs of poor adherence to antipsychotic medication, population-based processes for improving medication adherence are ripe for investigation.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Marc Glassman, Ph.D., for assistance with the data analysis.