The rights of hospitalized psychiatric patients has been a topic of increasing interest and controversy. Despite important legal, clinical, and ethical advances in this area, little research has been conducted, and no study has directly assessed and compared the attitudes of patients and staff members.

There has been much debate about the benefits and risks of various interventions and the extent to which psychiatric patients have the capacity to evaluate these interventions and thus maintain the right to be active in choosing and planning their treatment (

1). Some researchers have described deprivation of patients' rights—at least temporarily—as a gross violation of patients' autonomy, freedom, and dignity, whereas others have viewed such measures as preserving patients' autonomy, or even helping to restore it, by alleviating a condition that limits autonomy (

2). The question becomes most complex when there is a conflict between patients' rights and staff members' evaluation of clinical needs (

3). Staff want to provide treatment, but resistance to treatment is in fact common (

4). In such a situation, each patient's clinical condition, the potential risks and benefits of various forms of treatment, and the risk associated with no intervention need to be considered (

5,

6).

In Israel, the rights of psychiatric patients and the methods of involuntary hospitalization were first defined in the Treatment of Mental Patients Act of 1955. This law was amended in 1991 (

7) and is the current legal authority. There are three general ways in which psychiatric hospitalization takes place in Israel: voluntary hospitalization, that is, upon the person's request; urgent hospitalization, whereby a person who enters a psychiatric hospital—regardless of how—can be hospitalized against his or her will for 48 hours if the hospital staff considers the situation to be urgent; and forced hospitalization, whereby a person can be hospitalized involuntarily if he or she is assessed by a psychiatrist and found to be floridly psychotic and a danger to self or others and refuses to be examined.

According to the law, patients who are hospitalized voluntarily cannot be treated or medicated against their will or without their consent. However, patients who are forcibly hospitalized can be treated against their will. In both cases, a separate consent—or ruling in the case of forcibly hospitalized patients—is needed for special treatments, such as electroconvulsive therapy. Seclusion or restraint can be conducted only under a physician's order and only when necessary for preventing danger to the patient or to others. Such orders are time limited, and specific regulations exist for related record keeping. During psychiatric hospitalization, patients have the right to correspond, receive visitors, keep personal belongings, and wear their own clothes. Patients are informed on admission about their rights and receive a pamphlet that states all their rights. The law addresses confidentiality and discretion about any patient information.

Because of the controversy surrounding many of these issues, the inherent impact of personal values and treatment trends, and the changing social context, the issues are far from settled. Therefore, it seems important to study attitudes about treatment and about the conditions under which treatment may or may not be justified, even against a patient's will, from diverse perspectives. Particularly important are the viewpoints of the mental health practitioners who make treatment recommendations according to their evaluation of clinical needs and the viewpoints of the patients whose lives are directly influenced by such decisions.

The few studies that have compared the attitudes of staff and patients have typically focused on treatment-related issues and have found major differences in the way they perceived responsibility (

8,

9,

10,

11), treatment clarity (

12,

13), patient involvement (

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19), treatment goals and curative factors (

20,

21), and effectiveness (

22,

23,

24,

25).

The purpose of this study was to assess and compare patients' and staff members' attitudes about what the rights of hospitalized psychiatric patients should be. Specifically, we chose to assess patients' and staff members' attitudes about the most prominent and controversial aspects of patients' rights that have been identified in the literature, including patients' right to obtain information about their illness and treatment, confidentiality rights, the right not to be subjected to treatment by force, the right to refuse treatment, the right not to be subjected to physical restrictions, and the right not to be hospitalized involuntarily.

Methods

Subjects

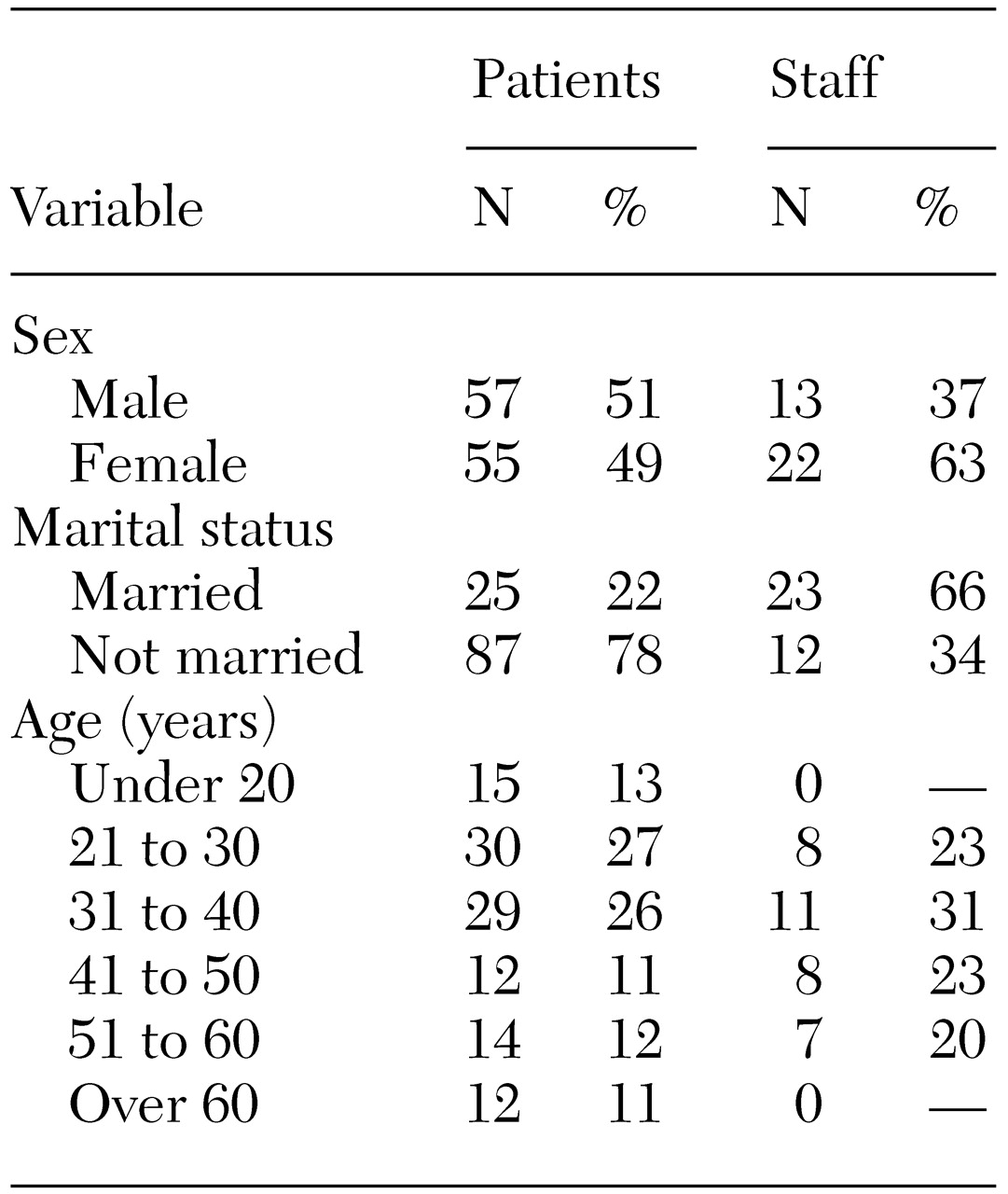

A total of 112 patients who were hospitalized in one of seven wards at a public psychiatric hospital in Israel were studied during 1996. This group of patients comprised almost all the hospitalized patients at the time who were able to fill out the consent form and complete the assessment instrument. The study patients ranged in age from 15 years to more than 70 years, with a mean±SD age of 33±16.4 years. About half of the patients were male (

Table 1). At the time of the study, 71 patients (63 percent) were single, 14 (13 percent) were divorced, and 25 (22 percent) were married; the marital status of two patients was unknown. For 38 patients (34 percent), this was their first hospitalization; for 31 (28 percent) it was the second or third hospitalization, and 37 patients (33 percent) had been hospitalized at least four times; the number of previous hospitalizations was unknown for six patients (5 percent). Eighteen patients (17 percent) had completed nine years of school, and 72 (65 percent) had completed 12 years of school.

Sixty-four patients (57 percent) had received a DSM-III-R diagnosis of schizophrenia, 15 (13 percent) a diagnosis of a major affective disorder, and eight (7 percent) a diagnosis of an anxiety disorder; 25 (22 percent) had received another diagnosis or had not yet received a diagnosis.

The 35 staff members ranged in age from 21 to 60 years, with a mean± SD age of 36±10.9 years. Thirteen staff members (37 percent) were men, and 22 (63 percent) were women. At the time of the study, nine staff members (26 percent) were single, three (9 percent) were divorced, and 23 (66 percent) were married. The staff comprised 15 psychiatrists (43 percent), 11 nurses (31 percent), eight psychologists or social workers (23 percent), and two orderlies (6 percent). Fourteen staff members (40 percent) had up to five years of practical experience, six (17 percent) had between six and 20 years of experience, and 12 (34 percent) had more than 20 years of experience; the number of years of experience was unknown for three staff members (9 percent).

Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of patients and staff.

Instrument

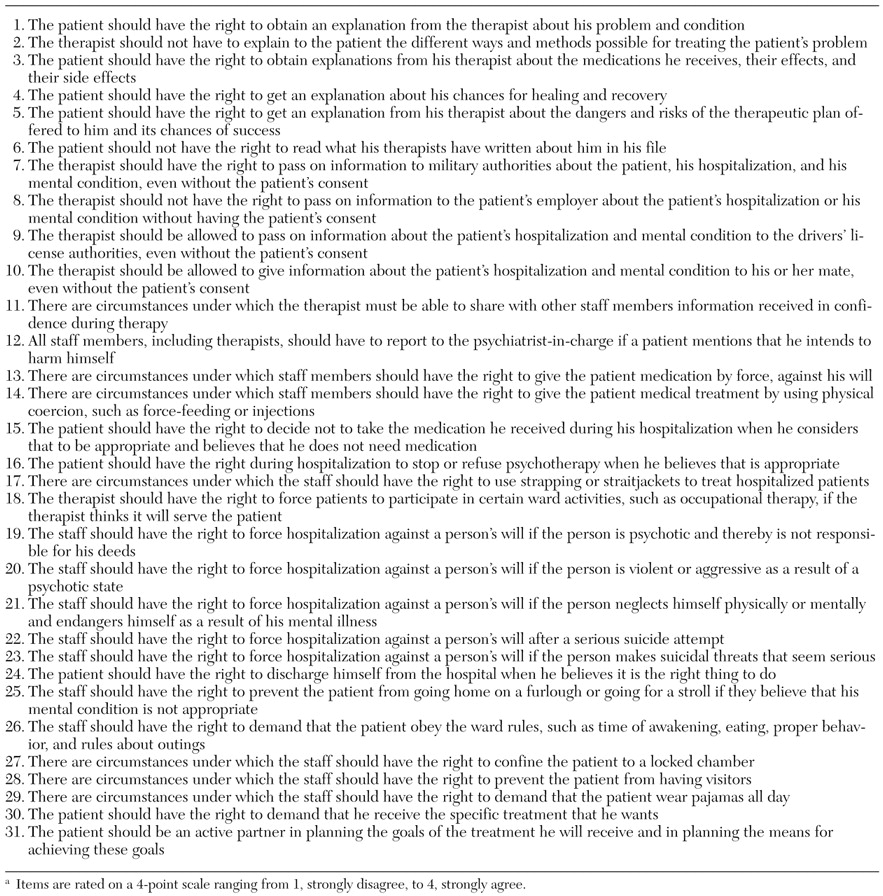

Although we conducted an extensive literature search with PsycLit and MEDLINE, we were unable to locate suitable instruments for eliciting attitudes about what rights hospitalized psychiatric patients should have. We thus developed an instrument in Hebrew; individual items, translated into English, are listed in

Table 2. We developed the instrument by reviewing the literature, identifying topics related to the rights of hospitalized psychiatric patients, and mining our collective clinical experience. This approach generated six key categories that we believe encompass the most substantial aspects of the perceived rights of psychiatric patients. We were careful to word statements so that identical phrasing could be used for patients and staff. The instrument was tested on a sample of six patients and four staff members and was revised.

The final instrument included 31 statements on what rights hospitalized psychiatric patients should have, to be rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 1, strongly agree, to 4, strongly disagree. Each statement pertained to one of six clusters: the patient's right to obtain information on his or her illness and treatment, the right to confidentiality of information provided in therapy, the right not to be subjected to treatment by force, the right to refuse treatment, the right not to be restricted physically, and the right not to be hospitalized involuntarily. (Item 28 was not used in the analysis; thus these six clusters comprise 30 of the original 31 items.)

Procedure

Patients were approached in person, provided with a brief oral description of the study, and asked for their written consent before they were asked to complete the questionnaire. This phase of the study was conducted by an assistant who was not aware of the purpose of the study. The assistant also extracted information from the patients' charts, such as diagnosis, length of stay in the hospital ward, age at the time of the first psychiatric hospitalization, and number of hospitalizations. Subsequently, questionnaires were distributed to and collected from the staff members. All data were handled anonymously. The study was approved by the institutional review board according to the Helsinki regulations.

Data analysis

The internal consistency of the scales was tested with Cronbach's alpha (.46 for information on illness and treatment, .55 for confidentiality, .77 for forced treatment, .57 for nontreatment, .70 for physical restrictions, and .77 for forced hospitalization). Multivariate analysis of variance, controlling for age and sex, was used to compare the two groups. A modified Bonferroni correction was used to control for multiple comparisons by dividing .05 by the six clusters compared, resulting in acceptable probability levels of .008 or less.

Results

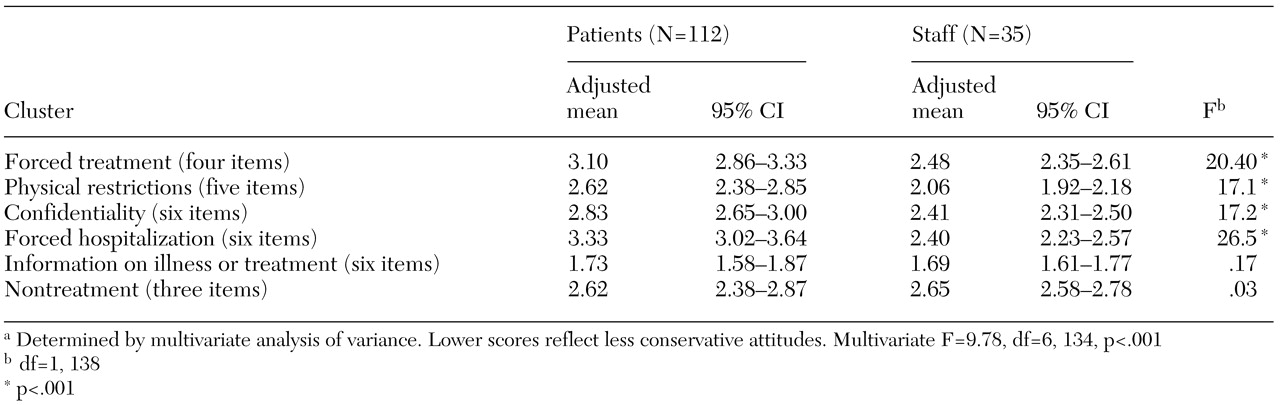

The attitudes of staff and patients are compared in

Table 3. Patients were less likely than staff to express the view that involuntary hospitalization, the use of force or physical restrictions, or the compromise of confidentiality is justified. There were no significant differences between staff and patients in attitudes toward patients' right to obtain information about their illness and treatment or their right to refuse treatment. No significant age- or sex-related differences in attitudes were found.

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that there were significant differences between staff and patients in four of the six clusters of patients' perceived rights. Specifically, there were differences between groups in terms of situations that justify involuntary hospitalization, the use of force or physical restrictions, and compromise of confidentiality. Areas in which no differences were observed were patients' right to obtain information about their illness and treatment and their right to refuse treatment. This pattern seems to indicate that the differences in viewpoints between staff and patients about what rights hospitalized psychiatric patients should have were greater for proposed interventions that involved more drastic compromises of patients' rights.

The most consistent finding of the study was the direction of the disagreement: staff members were always more likely to express the view that patients' rights should be compromised when they conflicted with what could be understood as a clinical need.

Our main findings seem to support the often-exaggerated stereotype of mental health professionals as being authoritarian and not always sensitive to patients' rights. However, it might also be that both groups value patients' rights but that staff tend to be more willing to compromise these rights when they perceive them as conflicting with patients' clinical needs. This difference may be a function of the way the two groups evaluate the potential benefit of treatment—even forced treatment—in relation to the potentially negative impact of restricting rights.

The patients' attitudes seemed to conform more closely to the "rights-driven model," which gives priority to patients' rights, whereas the staff members' attitudes appeared to be closer to the "treatment-driven model," which endorses a right to object to treatment but not a right to refuse it (

26). This approach is consistent with Stone's "thank-you theory of paternalistic interventions" (

27). Stone argued that patients who initially resist intervention will later appreciate having received benefits that ameliorate suffering.

The results of some studies lend support to the justification of paternalistic interventions by showing equal levels of satisfaction and positive attitudes between voluntarily and involuntarily admitted patients at discharge (

28,

29). Other studies have shown the diminished ability of psychiatric patients to understand decisions about hospitalization and treatment compared with patients in a general hospital (

30,

31).

In contrast, Cournos (

32) challenged the justification of paternalistic interventions for psychiatric patients. Drawing together findings from her extensive review of the literature, she concluded that medical patients and psychiatric patients do not necessarily differ in their ability to make health care decisions. Furthermore, she pointed out that little is known about the long-term usefulness of coercing patients to accept treatment that they do not agree with. Indeed, a heterogeneous survey of mental health consumers showed that almost half avoided treatment because they feared involuntary commitment (

33).

The results of our study may also reflect "professional socialization"—a state in which members of a certain profession, as a result of their education, their upbringing, or the norms and ideas of their profession, have viewpoints that are unique to them (

34,

35). The results of our study suggest that professional socialization may sometimes blind the members of a profession to the common consent about an issue.

Recognizing that such differences exist seems important in its own right. The results of this study indicate a profound conflict in the way patients and staff believe several everyday situations that come up in the ward should be dealt with and what principle should prevail—patients' rights or clinical needs as perceived and understood by the staff. Our results suggest a need to create groups in which both patients and staff participate so that sources of potential disagreement and conflict that may be impeding the treatment process can be dealt with.

In a therapy group at a day treatment program led by the first author, we conducted a role-play in which the patients acted out an interview with a patient to decide whether to hospitalize him. One patient played the role of the staff member conducting the interview, another played the role of the patient, a third played the role of the patient's parent, and the remaining patients voted on whether the patient should be hospitalized. The role-play stimulated much thought and discussion and provided a unique opportunity to consider the complexity of the problem and the various viewpoints. This type of therapeutic work may facilitate the important process of building bridges to overcome the gaps such as those revealed in this study.

Further research should explore whether the differences in attitudes between staff members and patients are a result of different value systems or simply a difference in the way each group weighs the potential benefits of treatment in relation to the restriction of rights. Another potentially interesting line of research would be a comparison of the attitudes of staff members and patients in a general hospital as a means of exploring whether this issue is specific to psychiatric patients or pertains to medical patients as well.