The cost of mental health care has been of increasing concern in recent years, resulting in concerted efforts to establish methods for delivering high-quality care at the lowest possible cost. One of the clearest results of this effort has been a large-scale reduction in the number of inpatient mental health beds, particularly in publicly operated institutions, and an attempt to shift emphasis from inpatient care to less costly community-oriented outpatient care (

1,

2,

3). However, as public systems have faced increasing restrictions on the ability to care for persons with mental illnesses, there has been concern that the most vulnerable populations—such as the severely disabled, persons with dual diagnoses, and homeless persons with mental illness—are the most likely to suffer from reduced access to care (

1,

4,

5).

Many vulnerable low-income populations already have limited access to mental health care (

5). Without adequate private insurance to treat mental illness, they must seek care from publicly funded systems such as state mental health authorities or the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). Reductions in access to needed mental health services in any given system are likely to have one of two effects: either patients go without services or they negotiate access to an alternative system of care. There is only a small body of literature on the extent of cross-system use by users of mental health services, largely because of the difficulty in collecting adequate data from multiple systems of care (

6,

7).

The literature on cross-system use can be divided into system-level studies of how changes in one system of care affect systems in the same geographic area, and individual-level studies of changes in individual patterns of service use in response to restrictions or changes in the availability of services. In an example of the first type of study, a recent national survey of mental health providers indicated that two-thirds of hospitals that provided inpatient psychiatric care transferred patients to other systems of care once the patients' insurance coverage had been exhausted (

8). Similarly, data from VA populations have shown that lower expenditures on state-funded mental health care are associated with greater use of VA services (

9) and, conversely, that greater funding of VA mental health facilities is associated with lower use of state hospitals by veterans (

6). These studies indicate that the amount of mental health spending in any given system of care may directly affect the use of adjacent systems of care.

However, data from the second type of study—individual-level studies—indicate that changes in expenditures within one system of care have only modest effects on the behavior of individual patients. Studies of cross-system use of services by individual veterans living in Philadelphia (

7) and in a national sample of VA mental health patients (

10) indicate that rates of cross-system use are low, with between 10 percent and 23 percent of VA patients using non-VA care. In addition, cross-system use accounts for only a small proportion of the overall costs of mental health care (

6,

9).

The chief limitation of the existing studies of cross-system use is the age of the data: all the data on cross-system use that have been published thus far were collected in the late 1980s or early 1990s. However, substantial changes have occurred in the provision of mental health care since that time. One major change has been an increase in the use of managed care principles by state mental health authorities to limit the use of state services (

11,

12). Colorado is one state that recently implemented such practices.

We used data on both VA and state mental health service use in Colorado to examine the effects of the implementation of managed care in the state mental health system on rates of cross-system use by veterans. We hypothesized that as managed care was implemented in Colorado, access to state mental health services would decrease and veterans would respond by using VA facilities more exclusively for their mental health care, and thus that rates of cross-system use would decline over time.

Colorado implemented managed care for mental health services in most of its counties between 1995 and 1997 (

13). However, some counties (11 in total), including the most populated (Denver), did not implement managed care until June 1998. Thus we were able to compare the effects of managed care across counties.

Operationally, the implementation of managed care in Colorado meant a shift from Medicaid reimbursement on a fee-for-service basis to capitated payments for the expected number of patients, calculated on a monthly basis. A majority of care was still provided by local community mental health centers, but three counties had cooperative agreements with private managed care companies to provide mental health services. Reimbursement was calculated on the basis of historical use of services at mental health facilities by clients in various age and disability groups. Reimbursement rates were calculated individually for each facility or mental health authority. State regulations mandated that capitation costs could not exceed 95 percent of the costs that would have been paid on a fee-for-service basis.

Although lower costs were thus legislatively mandated, there were no mandated procedures for restricting access to care—for example, utilization review. However, preliminary survey data from a longitudinal study of the effects of the implementation of managed care showed that use of both inpatient and outpatient services was significantly lower than in areas where managed care had not been implemented, for both adults and children (

13,

14). This decrease in service use was accomplished through various standard managed care practices, including organized efforts to monitor high-risk patients more closely to prevent hospitalization, the use of alternatives to traditional inpatient stays, reductions in "standard" lengths of stay, and preauthorization for both inpatient and outpatient services.

We examined administrative data for veterans who had used any VA mental health services between fiscal years 1995 and 1997 and calculated annual rates of use of both state and VA mental health services (cross-system use). Specifically, the analysis addressed four questions. First, what were the rates of cross-system use by veterans in this sample? Second, did these rates change over time? Third, did service use change at a different rate in the counties that had implemented managed care than in the other counties? And fourth, what individual factors predicted cross-system use?

Methods

Sample and data sources

The data for this study came from several sources. First, all male patients who had used any VA mental health services and who were residing in the state of Colorado between July 1, 1994, and June 30, 1997, were identified from VA administrative databases—the Patient Treatment File and the Outpatient Care File, which together record all inpatient and outpatient services delivered in the VA system. Patients who had used VA mental health services were identified on the basis of whether they had used services that were designated in the VA administrative data as specialty psychiatric or substance abuse programs. The cohort was restricted to males because of the low proportion of women served in the VA system (about 5 percent), which makes gender comparisons impractical.

Once the male VA mental health care users had been identified, the data were merged with administrative data from Colorado's state mental health authority. Social Security numbers were not recorded in all the state administrative databases, so dates of birth and names were used to match records.

The resulting cohort consisted of all male veterans who had used VA mental health services between 1994 and 1997, some of whom had also used state mental health services during that period. We were able to identify only whether a veteran had used any state mental health services, because data on the use of specific services were not available. All personal identifiers, such as name and date of birth, were removed for confidentiality reasons before the data were analyzed. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by a human investigations committee.

Validation of the data merge

Because Social Security numbers were not available for all state mental health patients in Colorado, we conducted a validation study with a subsample of patients who were treated in Colorado's state mental hospital at Pueblo and for whom Social Security numbers were available. This substudy was used to determine whether our matching criteria would adequately identify persons who were included in both data sets. Using the matching criteria described above, we were able to successfully match 384 of 469 veterans (82 percent) who were found to have used both VA and state hospital systems during the study period on the basis of a match of Social Security numbers. Discrepancies were accounted for primarily by the fact that older patients were less likely to have an accurate match on name and date of birth, possibly because long-term elderly psychiatric patients have more errors in their recorded date of birth. However, on average the validation test indicated that matching date of birth and name was a reasonably accurate method that would not result in any systematic bias.

Data analysis

Data analysis proceeded in several steps. First, we calculated, for each year, the rates of cross-system use by VA patients. Second, we examined the bivariate association between several patient variables and cross-system use. These variables fell into two categories: personal characteristics and VA health service use variables. Personal characteristics included age, dual diagnosis, whether the veteran lived in a county that implemented managed care between 1995 and 1997, and the distance in miles between a veteran's home and the nearest VA and non-VA hospital. Distances were calculated by using mapping software and represented the linear distance between the geographic center of the veteran's ZIP code and the nearest VA and non-VA facility. Other sociodemographic variables, such as race or ethnicity, marital status, education, and income, were not routinely available from the VA administrative data for the study period.

Service use variables consisted of categorical variables that indicated whether veterans had used any of a number of types of VA health services in fiscal years 1995 through 1997. These services were inpatient psychiatric care, inpatient substance abuse care, inpatient medical or surgical care, outpatient psychiatric care, outpatient substance abuse care, and outpatient medical or surgical care.

Bivariate analyses were used to identify any associations between personal characteristics, health service use, and cross-system use in fiscal years 1995 to 1997. These analyses allowed us to determine which characteristics were most important to include in the multivariate models. Because patients could have used or not used VA services in any given year and also could have used or not used state services in any year, we fitted a repeated-measures logistic regression model of cross-system use over time. The outcome of interest was use of both VA and state services in any given fiscal year.

There were three independent variables of interest: whether the veteran lived in a managed care county, the year, and interaction between managed care and year. Thus we were able to assess whether there was a trend in cross-system use over time, whether living in a managed care county affected the likelihood of cross-system use, and whether the effect of living in a managed care county changed over time. Control variables included age, use of VA inpatient and outpatient services, geographic distance to the nearest VA and non-VA facilities, and dual diagnosis. Age, diagnosis, and geographic distance were kept constant over the study period, whereas service use was allowed to vary by year in the repeated-measures models.

The final analysis was designed to determine whether the implementation of managed care in certain counties was associated with a shift to exclusive use of VA care. We examined rates of shift from use of state services to use of VA services and compared rates across counties that had implemented managed care and those that had not.

Results

A total of 10,950 veterans had used VA mental health services at some time between 1995 and 1997. Of these, 844 (7.7 percent) had used state mental health services in the same period. An upward trend was observed in cross-system use over time, although cross-system use was generally low throughout the study period. In 1995, a total of 172 of 5,966 VA users (2.9 percent) also used state services; in 1996, a total of 261 of 5,972 VA users (4.4 percent) also used state services; and in 1997, a total of 354 of 6,001 VA patients (5.9 percent) also used state services. In general, rates of cross-system use were consistently and significantly lower in counties that had implemented managed care policies: 2.7 percent compared with 3.4 percent in 1995; 4.1 percent compared with 4.9 percent in 1996, and 5.3 percent compared with 7.1 percent in 1997.

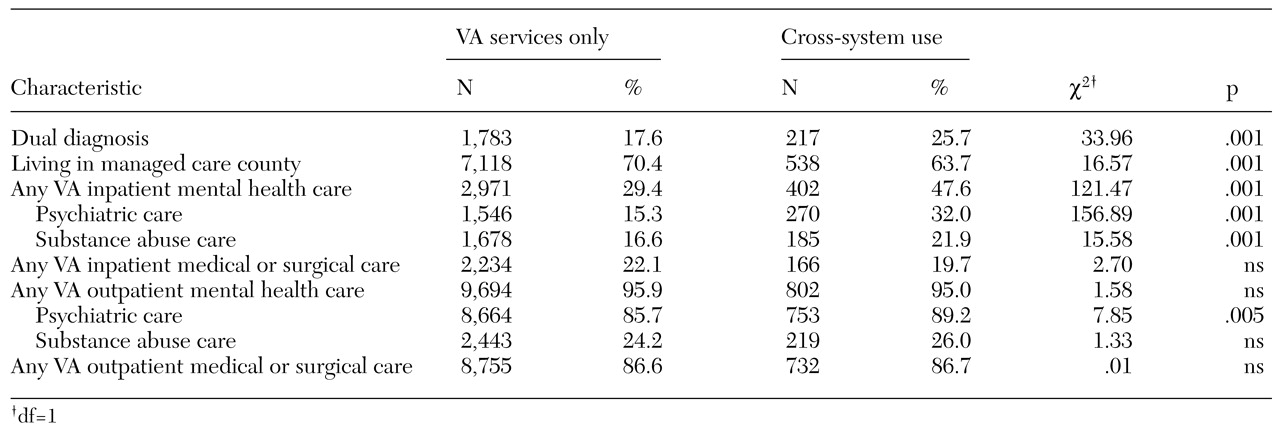

The distributions of categorical variables for VA-only and cross-system users are shown in

Table 1. Data are aggregated across all three fiscal years. Cross-system users were significantly more likely to have a dual diagnosis and significantly less likely to live in a managed care county. Cross-system users were also more likely to have used VA inpatient psychiatric or substance abuse services. Cross-system users were similar to VA-only users in their use of VA inpatient and outpatient medical or surgical care. Overall, the use of outpatient services was not significantly different between the two groups, but cross-system users were significantly more likely to have had at least one outpatient psychiatric visit.

Cross-system users were also significantly younger than VA-only users (a mean±SD age of 45±10.8 years compared with 47.4±12.7 years, p<.001) and lived farther from the nearest VA (a mean distance of 21.8±26.7 miles compared with 18.3±22.7 miles, p<.001) and nearer to the nearest non-VA hospital (4±6.9 miles compared with 4.9±7.4 miles, p<.001).

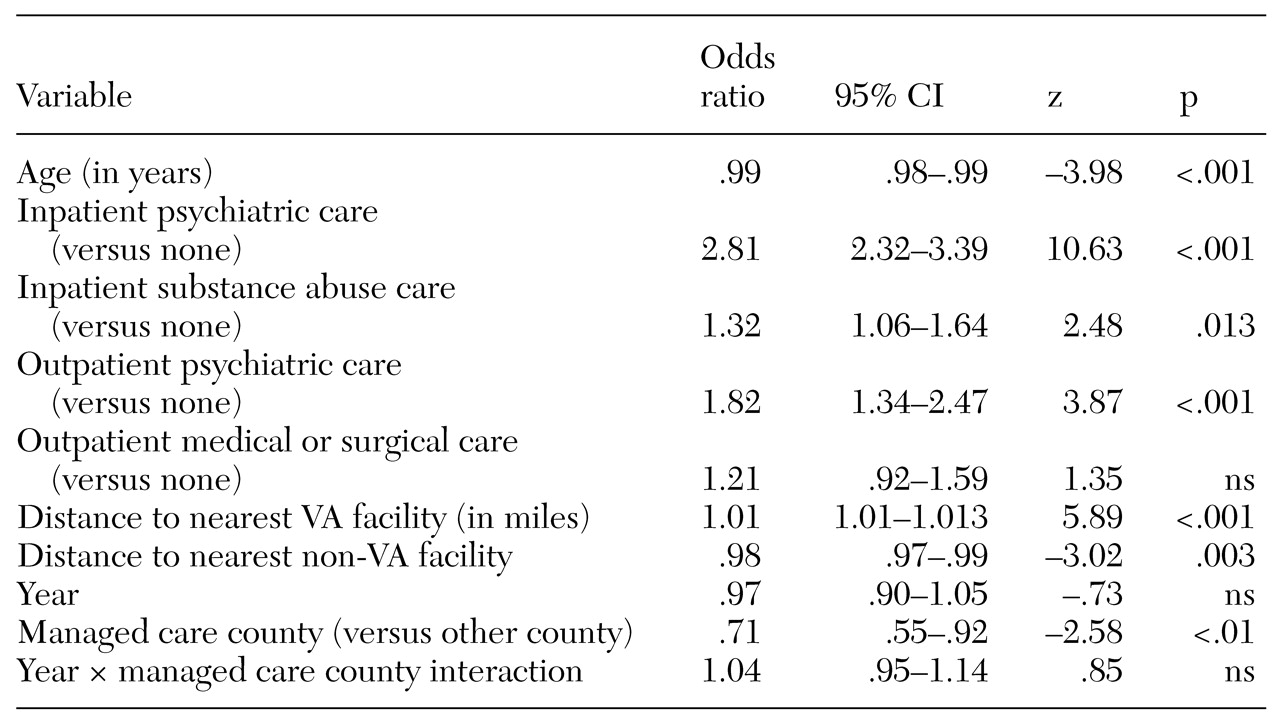

Time-series analyses predicting cross-system use indicated that living in a managed care county was a significant predictor of lower cross-system use, indicating that those who lived in a managed care county were less likely to be cross-system users than those who lived in a county without managed state mental health care. However, no statistically significant trend was observed over time in the rate of cross-system use, and no significant interaction was noted between time and residence in a managed care county (

Table 2).

Other significant predictors of cross-system use in multivariate analyses were age, geographic distance to VA and non-VA facilities, and VA service use. Older veterans were less likely to be cross-system users, and those who lived farther from a VA facility and closer to a non-VA facility were more likely to be cross-system users. Service use variables indicated that veterans who had a high level of use of VA services were more likely to also have used state services; those who had used inpatient psychiatric care, inpatient substance abuse care, or outpatient psychiatric care were more likely to have used state services in addition to VA services.

The final set of analyses examined whether residence in a managed care county was associated with shifts from use of state services to use of VA services. Because the study sample included all veterans who had used VA services in the three-year study period, some patients could have been using state services and then shifted to VA services with the advent of managed care. We tested this hypothesis in several ways. First, we determined which patients had used only state services in 1995 but had then used VA services in 1996 or 1997. Stratified by managed care counties, 1.6 percent of those who were living in a managed care area met these criteria, compared with 2 percent of those who were living in counties that had not implemented managed care.

Second, we determined which patients had exclusively used state services in 1995 or 1996 and had used no VA services until 1997. In managed care counties 3.4 percent of the sample met these criteria, compared with 4.2 percent in other counties.

Finally, we determined which patients used any state services during the study period but only started using VA services in 1997. In managed care counties 7.5 percent of the sample met these criteria, compared with 8.3 percent in other counties. Overall, no association was found between residence in a managed care county and a shift over time from state to VA mental health care.

Discussion

Taken together, the results of these analyses indicate that rates of cross-system use of VA and state services in Colorado was relatively low, that the advent of managed care in the state system was not associated with higher cross-system use over time, and that living in a managed care county was not associated with a shift over time from state care to VA care.

These results have a number of important implications for both state and VA systems of care. First, the rates of cross-system use we found—which are more recent than data from other studies of cross-system use—indicate that rates have continued to be fairly low, despite tremendous cost restrictions in recent years. This could be another indication that cost restrictions have thus far had little impact on individual patients' behavior.

However, these data also indicate that although there was no apparent increase in the effect of managed care policies over time, VA patients who lived in counties that had implemented managed care were less likely to be cross-system users than those who lived in other counties. This finding is likely to be a result of selection bias. Rural communities were more likely to have implemented managed care, whereas urban centers such as Denver—which also houses Colorado's major VA hospital—did not implement managed care during the study period.

The association we found between high levels of VA service use and cross-system use suggests that some VA patients were supplementing their VA care with non-VA care. These data do not clearly indicate why this happened, but several possibilities deserve comment. Patients may prefer to get certain types of care from VA facilities, such as care for posttraumatic stress disorder, but get other types of care, such as substance abuse care, from state facilities. They may face restrictions on certain types of care in the VA system, such as inpatient care, or they may want or need very high levels of care and learn to negotiate as many systems as possible to get it.

In 1996 the VA began a major restructuring of mental health programs and as a result reduced its number of inpatient mental health beds by as much as 60 percent nationwide. In Denver the number of inpatient beds dropped by 48 percent, from 87 beds in 1995 to 45 in 1997 (

15,

16). Several studies have been conducted to determine whether elimination of VA beds resulted in spillovers to state systems or to the criminal justice system (

11,

17,

18). These studies indicated little, if any, spillover effects. However, reduced access to inpatient care in the Denver VA may have served as an equalizing force against the pressure of reduced access to state care after the implementation of managed care, which may be why we found little effect of managed care over time.

Distance to facilities as a proxy for the convenience of access has been repeatedly demonstrated to be a strong predictor of service use (

9), and our findings are no exception. Not surprisingly, veterans who lived farther away from a VA facility were more likely to be cross-system users than those who lived closer. In addition, those who were younger—and presumably more mobile and better able to travel distances—were more likely to be cross-system users. However, age may also be an indicator of identification with the VA system—older veterans may have invested more time and energy into their VA care and their clinicians than younger patients, and they may prefer to continue that relationship over time.

Although these data are somewhat reassuring in that managed care did not appear to result in widespread shifts in access to care in either the VA or the state mental health system, there were limitations to the data. First, the lack of a personal identifier such as a Social Security number in both VA and state data reduced the accuracy of the data merge. Although we do not suspect that this resulted in any systematic bias related to cross-system use, it may have resulted in underestimates of the extent of cross-system use.

Second, data on the intensity of use of state mental health services were not available. If these data become available, they may be helpful for exploring shifts in the relative intensity of service use across systems. Although we found no major shift in access as measured by use of any service in a given fiscal year, there may have been a shift in the intensity of service use across systems. For example, although overall access to state care may not have been restricted over time, restrictions in length of stay or access to particular types of high-intensity services, such as inpatient care, may have been reduced over time. This hypothesis is consistent with preliminary data from other studies of the managed care shift in Colorado, which showed no overall reduction in access but significant reductions in costs per patient. Overall service expenditures dropped by about 18 percent, with a 31 percent decrease in inpatient costs but a 4 percent increase in outpatient costs (

14).

Third, we were unable to determine which of the VA patients were Medicaid eligible. This limitation is important, because veterans who were not Medicaid eligible would not have had access to state services. In addition, as a result of VA pension and disability payments to disabled veterans, many veterans are not eligible for Medicaid because of income restrictions. Thus the generalizability of our results is limited. However, veterans who do not receive such payments are also those who are most likely to be cross-system users, namely those with a substance abuse diagnosis and those with dual diagnoses. In addition, we were interested in whether veterans were forced out of the state system over time, and veterans would have had to have been Medicaid eligible to be included in the state data.

Finally, the managed care data may have been confounded by selection bias in terms of which counties had implemented managed care. Rural counties were more likely to have implemented managed care. Veterans living in these counties would have had to travel greater distances to receive any type of care, state or VA, and thus the effect of managed care may have been overpowered by the limitations of geographical access. As data are collected in other parts of the country, the effect of geographical access should be explored further.

Conclusions

These data indicate not only that cross-system use is fairly low but also that the advent of managed care practices in Colorado had a fairly benign effect in terms of producing system shifts and spillovers. We found no evidence that veterans were forced out of the state system or that cross-system use increased over time as a result of managed care. In addition, preliminary data from other researchers suggests that although the implementation of managed care in Colorado lowered the costs of care, as evidenced by lower use of costly inpatient services, clinical outcomes were unaffected (

13,

14). It is likely that a small proportion of veterans will continue to receive mental health services from both VA and state service systems and that managed care will not affect that pattern, but managed care interventions may have a moderate effect on the intensity of service use.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Diana Truax, Rosann Barentson, and Pat Ison for their assistance in obtaining and interpreting the data as well as Howard Goldman, M.D., and Vera Hollen. This work was supported in part through grant MH-5R24 MH-53148 from the Research Infrastructure Support Program of the National Institute of Mental Health.