Correcting errors and significant ambiguities

In the years since DSM-IV was published, several errors and problems have been identified in the definition of some disorders and in the implementation of specifiers and other diagnostic conventions. Although major changes to criteria sets were off limits, the text revision was an opportunity to correct such errors. Because each of these changes may have an impact on the day-to-day use of DSM-IV, they are discussed in some detail below.

Clarification of the definition of pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified. In DSM-IV, major changes were made in the category of pervasive developmental disorders. The changes were based in part on a large multisite international field trial. However, an editorial change was made in the description of pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDDNOS) during the final phase of production of DSM-IV that had an unintended effect on the definition of this disorder. Instead of requiring "impairment in the development of reciprocal social interaction and of verbal and nonverbal communication skills," as DSM-III-R indicated, DSM-IV states that the "category should be used when there is a severe and pervasive impairment of reciprocal social interaction or verbal and nonverbal communication skills, or when stereotyped behavior, interests, and activities are present." Thus a child with an impairment in only one area—for example, a child with stereotyped behavior, interests, and activities but without evidence of disturbed social interactions—could theoretically qualify for a diagnosis of PDDNOS.

To assess the impact of the

DSM-IV rewording, Volkmar and colleagues (

12) conducted a series of reanalyses of the

DSM-IV data from the autism-pervasive developmental disorder field trial. When clinicians' judgment of the presence or absence of PDDNOS was used as the standard, the

DSM-IV wording for this disorder had a sensitivity of .98. However, the specificity was only .26—that is, about 75 percent of children identified by clinicians as not having the disorder (true negatives) were incorrectly identified as having it according to

DSM-IV. These results lend support to the concern that the

DSM-IV wording inappropriately broadened the construct of PDDNOS. If the diagnosis requires impairment in the social area and either problems in communication or restricted interest—that is, if at least two types of problems must be present, one of which must be from the social area—the sensitivity was .89 and the specificity .56.

These results supported a change in the wording of PDDNOS to revert to the original construct. The new wording in DSM-IV-TR is as follows: "This category should be used when there is a severe and pervasive impairment in the development of reciprocal social interaction associated with impairment in either verbal and nonverbal communication skills, or with the presence of stereotyped behavior, interests, and activities, but the criteria are not met for a specific Pervasive Developmental Disorder, Schizophrenia, Schizotypal Personality Disorder, or Avoidant Personality Disorder."

Removal of the clinical significance criterion from the criteria sets for tic disorders. A clinical significance criterion—"the disturbance causes clinically significant distress or impairment"—was added to the criteria sets of a majority of disorders in

DSM-IV, tic disorders among them, to emphasize that a mental disorder should not be diagnosed in trivial cases, such as when the disturbance is so mild that it has little impact on the patient. The addition of the clinical significance criterion has been the focus of some criticism (

13).

According to

DSM-IV criteria, a diagnosis of tic disorder can be made only after it is established that the tic causes clinically significant distress or impairment in the child. After the publication of

DSM-IV, concerns about the appropriateness of this criterion were raised by clinicians, researchers (

14), and patient advocacy groups, such as the Tourette Syndrome Association. For example, clinicians have expressed concerns about not making a diagnosis in the case of a child whose presentation clearly meets the tic symptomatology criteria for Tourette's disorder but who does not have significant impairment or distress from the tic, a situation quite common in clinical practice. Thus this criterion has been eliminated from the criteria sets for Tourette's disorder, chronic vocal or motor tic disorder, and transient tic disorder.

Adjustment of wording of the clinical significance criterion for the paraphilias. In DSM-III-R, the criteria sets for the paraphilias included a clinical significance criterion—"the person has acted on these urges, or is markedly distressed by them"—to indicate that the mere presence of paraphilic sexual urges or fantasies does not invariably warrant a diagnosis of a paraphilia. During the preparation of DSM-IV, the wording of this criterion was adjusted as part of the effort to adopt uniform wording for the clinical significance criterion across the disorders. The DSM-IV wording is as follows: "the fantasies, sexual urges, or behaviors cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning."

An unforeseen consequence of the rewording was that it led to confusion about the

DSM-IV definition of pedophilia (

15). Specifically, the replacement of the

DSM-III-R phrase "acts on these urges" with the phrase "causes clinically significant … impairment" was misconstrued to represent a fundamental change in the definition of pedophilia. Some readers misunderstood the new wording as greatly restricting the number of individuals who would receive a diagnosis of pedophilia by requiring that these persons be distressed by their behavior in order to qualify for the diagnosis. This implication was never intended, as it is well recognized that many, if not most, individuals with pedophilia are not distressed by their pedophilic urges, fantasies, and behaviors.

To remove any possible ambiguity about whether acting out pedophilic urges with others is sufficient for a diagnosis of pedophilia, the original DSM-III-R wording has been reinstated for pedophilia as well as for paraphilias that involve a victim who is a nonconsenting individual—voyeurism, exhibitionism, and frotteurism. Because some cases of sexual sadism may not involve harm to a victim, such as inflicting humiliation on a consenting partner, the wording for sexual sadism involves a hybrid of the DSM-III-R and DSM-IV text. The DSM-IV-TR version states: "the person has acted on these urges with a nonconsenting person, or the urges, sexual fantasies, or behaviors cause marked distress or interpersonal difficulty."

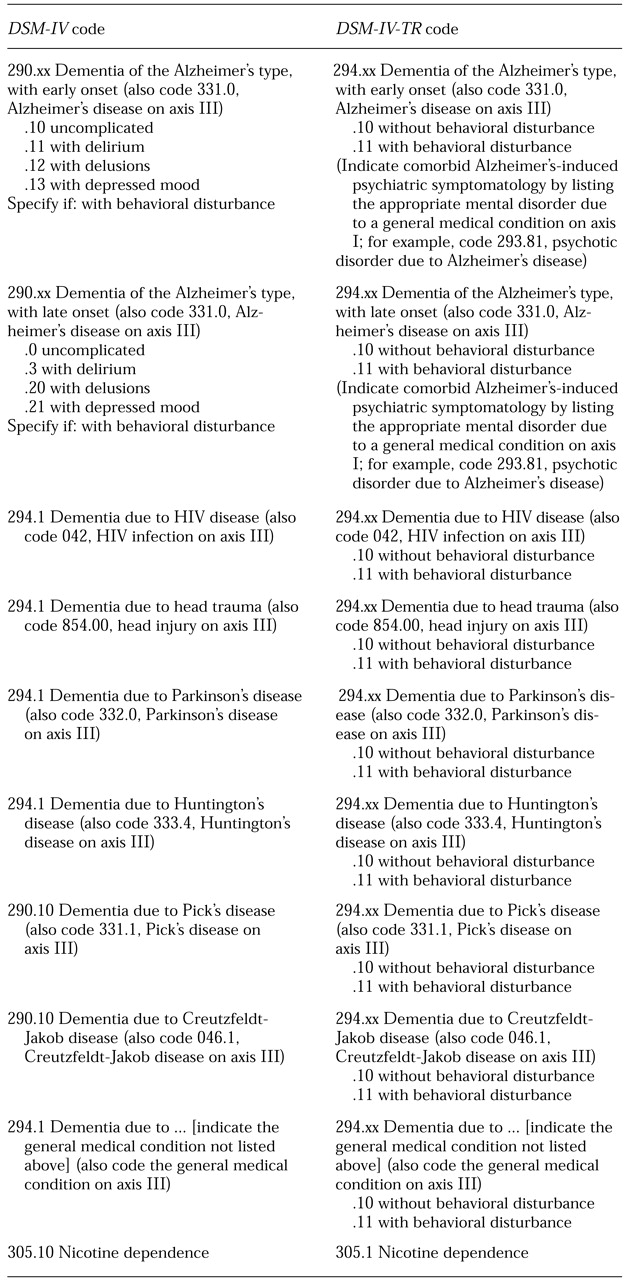

Change in coding conventions for indicating clinically significant psychiatric symptoms occurring as part of a dementia. An ICD-9-CM coding change has rendered the subtypes for dementia of the Alzheimer's type—that is, with delusions, with depression, and with delirium—obsolete. Now, all forms of dementia of the Alzheimer's type share the same ICD-9-CM diagnostic code (code 294.1). To indicate comorbid psychiatric symptoms arising from Alzheimer's disease, the new convention is to code the mental disorder that is due to Alzheimer's disease on axis I along with the dementia.

For example, under DSM-IV coding conventions, an individual with dementia of the Alzheimer's type who suffers from the delusion that aides in the nursing home are trying to poison him would have been given a diagnosis of 290.20, dementia of the Alzheimer's type, late onset, with delusions. In DSM-IV-TR, two diagnoses would be assigned: 294.11, dementia of the Alzheimer's type with behavioral disturbance, and 293.81, psychotic disorder due to Alzheimer's disease, with delusions. The potential list of secondary conditions to choose from include psychotic, mood, and anxiety disorder, personality change, and sleep disorder due to a general medical condition.

One complication that arises in DSM-IV is the fact that the criteria for personality change specifically prohibit it from being diagnosed in the presence of dementia. Criterion D states: "The disturbance does not occur exclusively during the course of a delirium and does not meet criteria for dementia." This exclusion was an inadvertent carryover from the DSM-III-R criteria set for organic personality disorder, which had an identical criterion D. Because the DSM-III-R criteria for dementia included personality change as one of the defining features, allowing organic personality disorder to be diagnosed along with dementia would have been redundant. When personality change was dropped from the criteria set for dementia, a diagnosis of personality change due to a general medical condition should have been allowed along with dementia. Thus criterion D in personality change due to a general medical condition has been changed so that it excludes only delirium.

Clarification of the procedures for making an axis V Global Assessment of Functioning rating. Lack of detail on how to use the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) rating have led to misinterpretations of how to apply the GAF. One source of confusion is how to operationalize the "current" time frame for the GAF. Does it refer strictly to how the patient appears and functions during the evaluation procedure? This interpretation might result in a misleadingly high GAF, given that some individuals may experience transient improvement in anticipation of receiving help. For clarity, the text now includes a sentence specifying that "in order to account for day-to-day variability in functioning, the GAF rating for the 'current period' is sometimes operationalized as the lowest level of functioning for the past week."

Another source of confusion involves how to integrate the potentially disparate contributions of a patient's psychiatric symptoms and functioning to the final GAF score. For example, what should the final GAF score be for a patient who is a significant danger to himself, which would justify a GAF rating below 20, but is otherwise functioning well at work and with his family, reflecting a GAF rating above 60? Some clinicians mistakenly use an average of the two, which in this case would result in a GAF score around 40. In fact, the final GAF score should always reflect the lower of the two ratings. In this case, the GAF score should be below 20, despite the patient's higher social and occupational functioning. A paragraph has been added to the GAF instructions to clarify this convention.

Clarification of the concept of polysubstance dependence. It is not uncommon for clinicians to inappropriately use the term "polysubstance dependence" in referring to heavy drug users who are dependent on a number of different types of substances. Instead, multiple comorbid diagnoses of substance dependence, one for each class of drug that the person is dependent on, should be given. For example, an individual who smokes crack several times a week, injects heroin daily, and smokes several marijuana cigarettes a day would receive three diagnoses—crack dependence, heroin dependence, and marijuana dependence—and not a diagnosis of polysubstance dependence.

A diagnosis of polysubstance dependence should be given only in clinical situations in which the pattern of multiple drug use is such that it does not meet the criteria for dependence on any one class of drug. In such a case, the only way to assign a diagnosis of dependence is to consider all the substances that the person uses, taken together as a whole. To clarify the appropriate use of this diagnosis, the text for polysubstance dependence was revised to provide examples of situations in which this diagnosis might apply.

In making these revisions, however, it became clear that more than one interpretation of how to apply the polysubstance dependence rule is possible. One interpretation, which is operationalized in the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (

16), focuses on periods of indiscriminate use of a variety of substances. Another interpretation is analogous to the concept of "mixed personality disorder"—that is, one or two dependence criteria are met for a single class of drug, but full criteria for dependence are met only when the drug classes are grouped together as a whole. Since both interpretations are covered by the construct of polysubstance dependence, the revised text includes elements of both.