The number of women in jail, in prison, on probation, or on parole in the United States has increased dramatically over the past 20 years and now exceeds 950,000 (

1). The number of female prison inmates increased from 7,389 in 1974 to 82,594 in 1999 (

2). Despite these increases, few studies have described the characteristics of female criminal offenders. We know that most have been arrested for a drug or property crime, have substance use problems, and are mothers (

3,

4,

5,

6,

7). Female criminal offenders also have a high rate of HIV infection (

8,

9,

10). Although studies with small samples or convenience samples have suggested that female criminal offenders have a variety of psychosocial problems (

11,

12,

13), research is needed to document the extent of these problems.

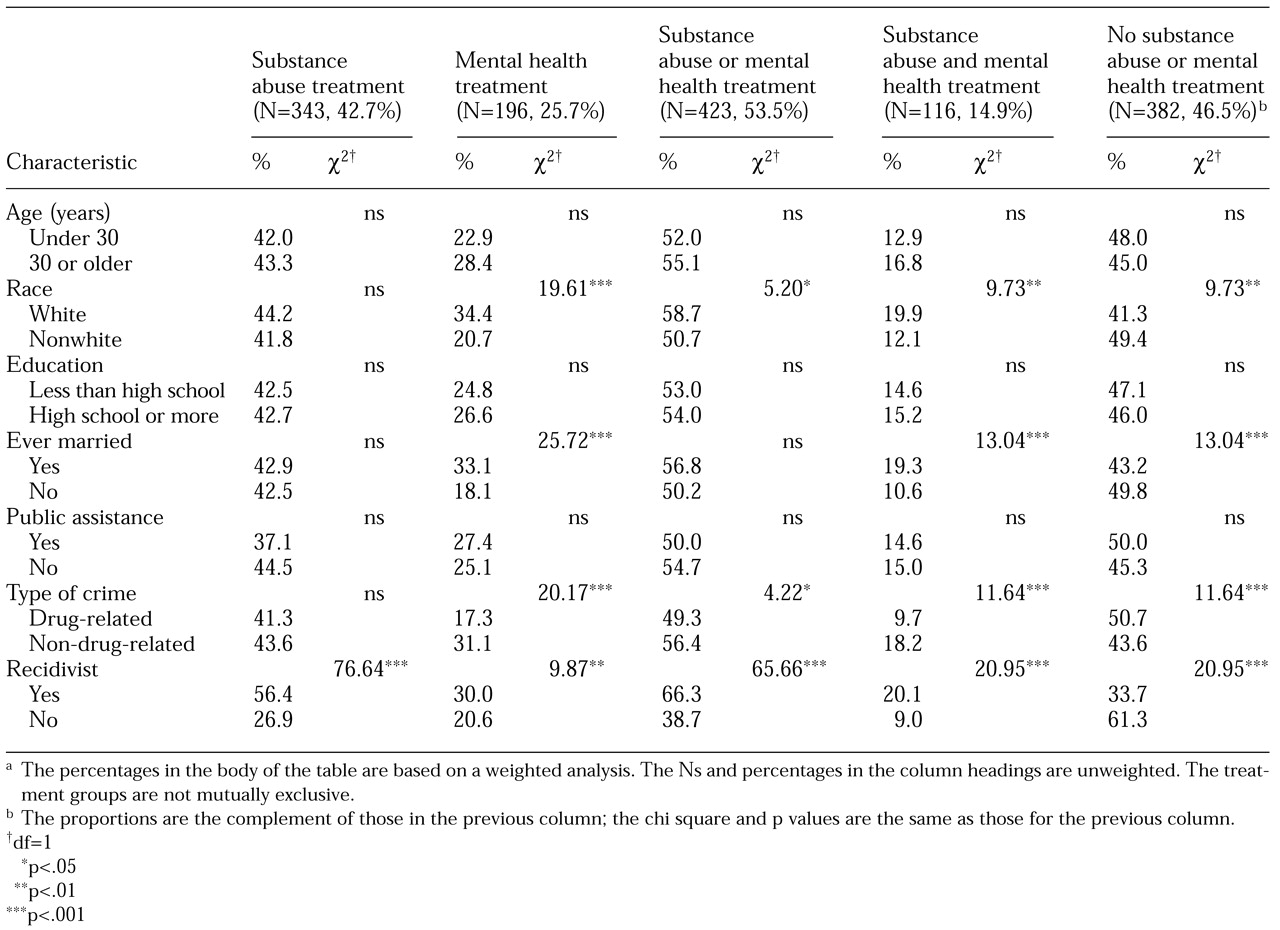

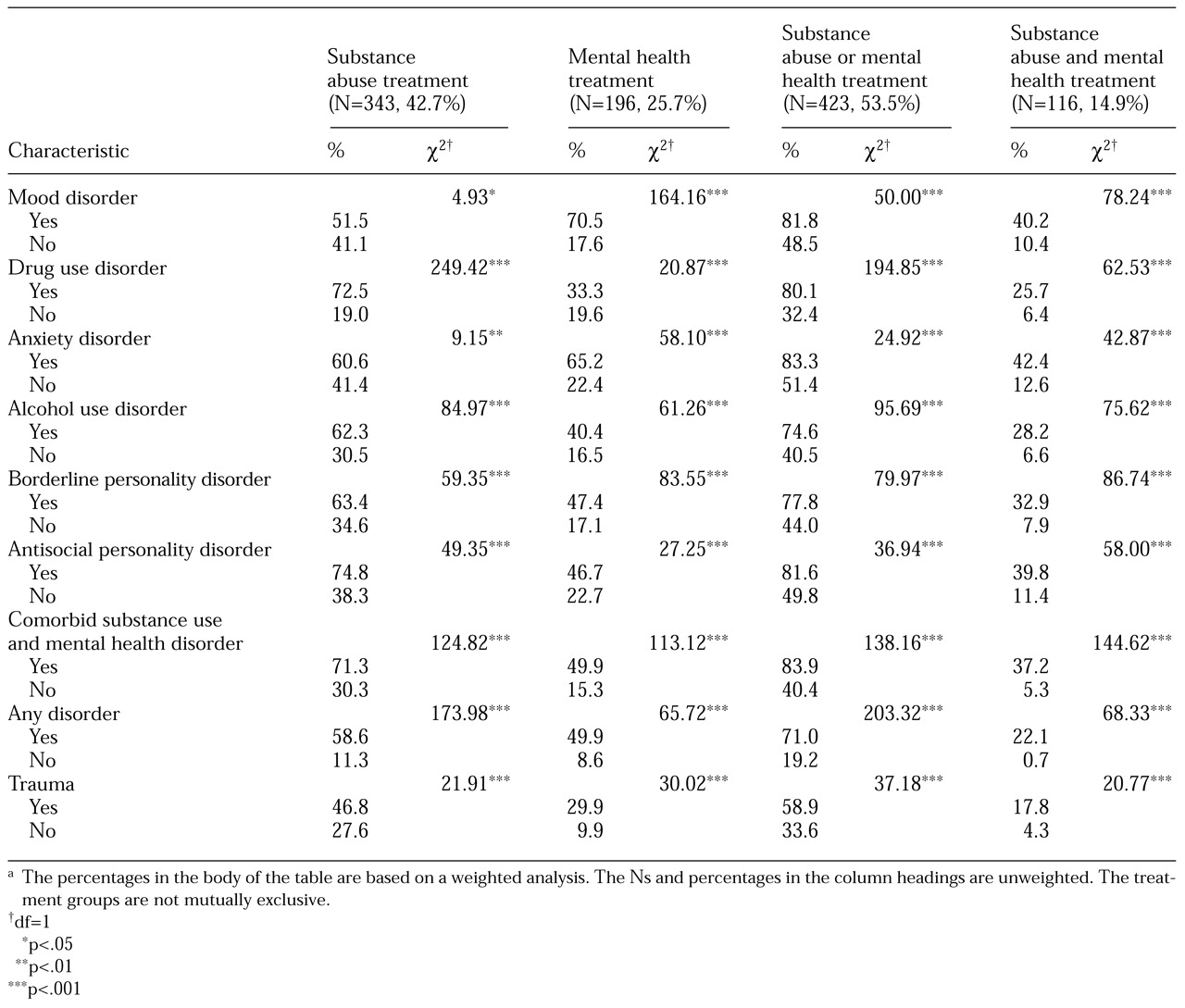

The purpose of this study was to deepen our understanding of the use of mental health and substance abuse treatment by incarcerated female felons. The study used data from the survey sample in the Women Inmates' Health Study to address the following research questions. First, among women recently imprisoned in North Carolina and assessed soon after incarceration, what are the bivariate relationships between the women's demographic and clinical characteristics and their lifetime use of mental health and substance abuse treatment services? For example, are white inmates more or less likely than nonwhite inmates to use such services? What proportion of women with a mood disorder have received mental health and substance abuse treatment, and how does this utilization rate compare with the rate for women without a disorder or with a different disorder? Second, in multivariate analyses in which the dependent variable is use of services versus no use of services, what characteristics or disorders are significantly related to the use of specific types of services, when the effects of all other independent variables are controlled for? Third, how do the utilization rates for mental health and substance abuse treatment services among female felons compare with rates for women from a community sample, if the effects of psychiatric and substance use disorders are controlled for?

Methods

The Women Inmates' Health Study

Data for the study were collected between 1991 and 1992 at the only prison to which newly sentenced female felons in North Carolina were admitted. (A felony is an offense for which the minimum sentence is one year or longer.) Study subjects included all women entering prison for a new felony charge during that period, except for a few months during which there was a large number of intakes, from which a random sample was selected. For the high-intake months, sampling weights were used to adjust for the probability of selection (

18). For example, if one of every three women was randomly selected in a month, the weighting for these subjects would be the inverse of the selection probability, which is three. Only 6 percent of the entire sample consisted of women who entered prison during the high-intake months. The subjects were interviewed shortly after intake. The study was approved by the Research Triangle Institute's institutional review board.

The survey interviewers for the Women Inmates' Health Study conducted 805 in-depth, face-to-face interviews in private. The mean duration of the interviews was 2.5 hours. Emphasis was placed on assuring participants that responses would not be shared with prison authorities or staff. Written informed consent was obtained, and a package of toiletries was the honorarium. The response rate was 95 percent; the remaining 5 percent were lost to follow-up, primarily as a result of transfer to another facility or release.

Assessment of psychiatric disorders

A detailed discussion of the instruments used for psychiatric assessment has been published elsewhere (

14).

DSM-III-R (

19) diagnostic criteria were used. Most specific psychiatric disorders were assessed with the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (

20,

21). Because the CIDI does not have a module that identifies antisocial personality disorder, the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (

22) was used to assess participants for that disorder. Because neither of the two instruments assesses borderline personality disorder, we used a modification of the borderline personality disorder module of the Diagnostic Interview for Personality Disorder, Revised (

23).

Rates of service use for North Carolina women inmates grouped by disorder were compared with rates for a sample of North Carolina women of comparable age from the Duke site of the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) survey (

24). More than 90 percent of the women in the ECA sample were community residents, and we refer to them here as the community sample. The ECA used the Diagnostic Interview Schedule and

DSM-III (

25) criteria. The CIDI was developed from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule, and rates of disorders found by using the two instruments should be similar.

The specific alcohol, drug, and mental health disorders considered in this analysis included mood disorders (major depressive episode and dysthymia), anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder), and substance use disorders (alcohol abuse and dependence and drug abuse and dependence), as well as antisocial personality disorder and borderline personality disorder. We chose not to assess psychotic disorders. The assessment of such disorders is time-consuming, and the prevalence estimates were expected to be low (1 to 2 percent) and thus possibly unreliable. In addition, the number of cases would have been too small to distinguish any significant effects for this group in multivariate analyses. The prevalence estimates reported here are lifetime estimates, that is, the disorder may have occurred at any time in the subject's life. We also assessed exposure to extreme or traumatic events (that is, criterion A for posttraumatic stress disorder) by using a modification of the instrument used by Resnick and colleagues (

26) in their national study of rape.

Service use

Treatment included both inpatient and outpatient services. Substance abuse treatment also included self-help groups, such as Alcoholics Anonymous, and detoxification.

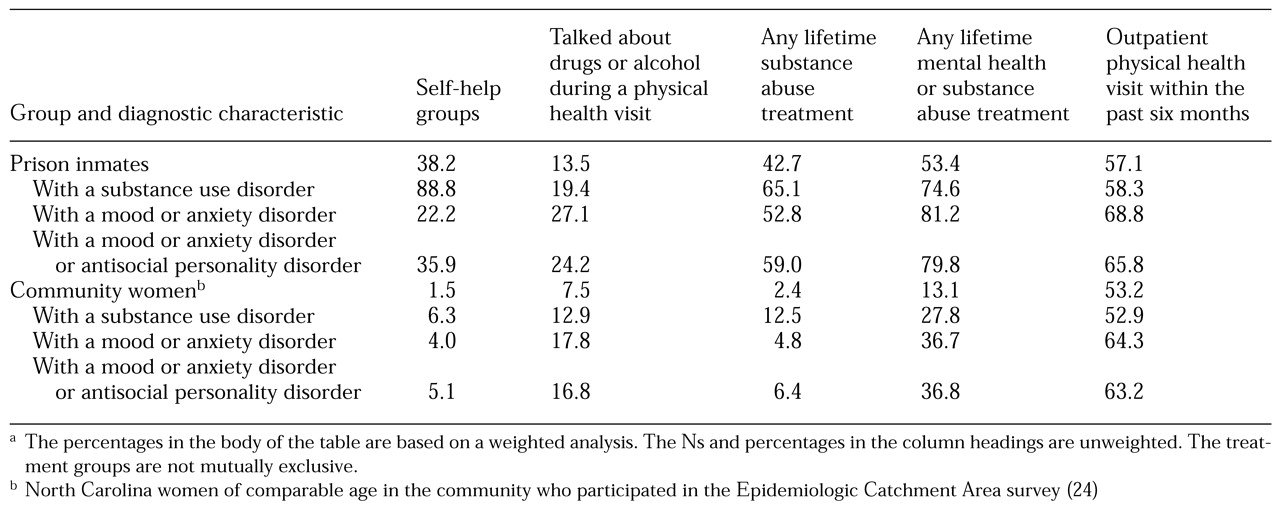

For the comparisons between the inmates and the women in the community, services were classified as self-help groups targeting substance use problems, discussions about drug or alcohol problems when visiting a health care provider for a physical health problem, use of any substance abuse treatment services, use of mental health treatment or substance abuse treatment, and use of outpatient services for a physical health problem in the previous six months. Besides allowing a comparison of the overall use of medical services between the two groups, the latter category of services was used as an indicator of overreporting. If inmates tended to overreport service use, their rates of reporting physical health services would have been higher than those of the community women.

Because the inmates were interviewed within days after their admission to prison, the services they reported were virtually all received before their current incarceration. We did not know whether any of the reported services were received during a previous incarceration.

Other variables

The demographic variables included age, race, education, and marital status. A dichotomous variable was used to identify women who indicated that public assistance was their primary income source at the time of the arrest. Another variable specified whether participants had been incarcerated for a drug-related crime or a non-drug-related crime. The two categories were mutually exclusive, and women who were incarcerated for both types of crime were included in the drug-related crime category. A recidivism variable identified women who had previously served time in jail or prison.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were weighted to account for the probability of selection and, for the ECA data, for design effects. Therefore, all reported statistics, including prevalence estimates, are weighted estimates. Sample sizes, however, are given as actual (unweighted) numbers. For the bivariate analyses, chi square tests were used to determine whether rates of service use varied by the levels of the independent variables.

In the bivariate analyses, the variables indicating use of any substance abuse treatment and use of any mental health treatment were coded independently of one another—that is, whether or not the woman used the other type of treatment. Thus the treatment groups overlapped, and the sum of the sample sizes across the groups is greater than 805.

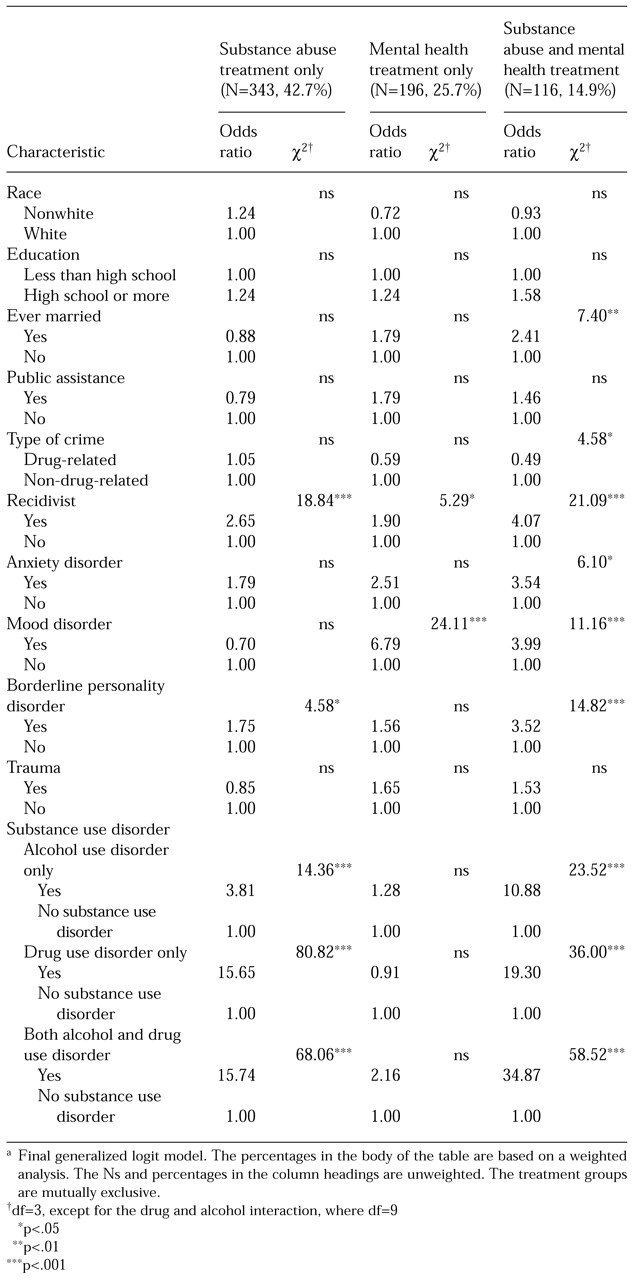

Next, a multivariate analysis was conducted to determine the relationship of the independent variables to different types of service use, with the effects of the other independent variables controlled for. For these analyses, a four-level variable was created in which the substance abuse treatment and mental health treatment groups were mutually exclusive—that is, the sample was divided into those who received only mental health treatment, only substance abuse treatment, both mental health and substance abuse treatment, and no treatment (the contrast group). Therefore, in the regression analyses, we used a multinomial (four-level) logit model that could accommodate nominal dependent variables (

27). The multinomial logit model was analogous to the use of three separate binary logistic regression models comparing mental health treatment only versus no service, substance abuse treatment only versus no service, and both mental health and substance abuse treatment versus no service. For each independent variable, such as recidivism, three sets of odds ratios were calculated: one for mental health treatment only, one for substance abuse treatment only, and one for mental health treatment plus substance abuse treatment—all three relative to no service use. For example, for recidivists the odds ratio for mental health treatment only was 1.9. Thus, recidivists were 1.9 times as likely as nonrecidivists to have received only mental health treatment than to have received no treatment.

With samples this large, the expected values of the estimates would be the same for the four-level model as for four separate binary regression models. The multinomial model had the advantage of lower variances.

In the final analytic step, which compared women inmates and community women, prevalence estimates and their associated standard errors were generated by using standard analysis weights for the ECA study. These analyses were conducted with the Crosstab procedure from the Survey Data Analysis (SUDAAN) statistical package to account for the complex sampling design of the ECA (

28).

Discussion and conclusions

In the bivariate analyses, we found that women with certain characteristics were more likely to use services than their counterparts. These characteristics were being white, married, or incarcerated for a non-drug-related crime, having previously served time in jail or prison, or having met lifetime criteria for a mental health or substance use disorder. For example, white women were more likely to use services than nonwhite women, and married women were more likely than unmarried women. When the effects of all other independent variables were controlled for, the multivariate analyses revealed that only the following attributes were significantly related to having received either substance abuse or mental health treatment or both: having previously served time in jail or prison, being married, being incarcerated for a non-drug-related crime, and meeting lifetime criteria for a substance use, mood, or anxiety disorder or borderline personality disorder.

One striking finding is that more than half of the women entering prison for a felony charge in North Carolina had received mental health or substance abuse treatment services at some time in their lives, and almost half of those who had received mental health services had received inpatient services. To put this in perspective, it is important to remember that the majority of these women had had a lifetime psychiatric or substance use disorder, and, despite high rates of previous treatment, almost half had a current disorder. The rate of mental health or substance abuse treatment for community women of similar age was about 13 percent.

Furthermore, at least three-quarters of the women inmates with a psychiatric or substance use disorder had received services for their disorder, compared with 28 to 37 percent of the community women with a disorder. Because the rates of use of physical health services among the inmates and the community women were similar, the differences between the groups do not appear to be explained by overreporting of service use by inmates. The differences between the groups may have been due to greater severity of illness among the inmates, whose symptoms may have been so severe that they may have engaged in illegal behaviors such as violent assault or stealing to get money for drugs.

Alternatively, the inmates, who tended to have low incomes, may have received public treatment that was unavailable to many community women with higher incomes. Or, because many inmates with a disorder had already spent time in jail or prison, they may have received assessment and treatment during previous incarcerations, as mandated by law. However, Teplin and colleagues (

15) and others have found that most individuals with psychiatric disorders who are incarcerated usually do not receive treatment. Furthermore, other findings suggest that the differences between the inmates and the North Carolina women in the ECA sample were not primarily the result of treatment during previous incarcerations: the rate of mental health and substance abuse treatment among first-time inmates was high; at the women's prison where the study was conducted, very few mental health treatment services were available; some studies have reported elevated rates of prior arrest and incarceration among community clients in substance abuse treatment and among psychiatric hospital patients (

29,

30).

Although the bivariate analysis found that trauma was related to lifetime service use, this relationship seems to have been mediated by the presence of a lifetime disorder, and the relationship was not found when the analysis controlled for the effects of disorder. Recidivism was the most robust predictor of service use among inmates.

These findings suggest that there is a subgroup of troubled women whose impairments result not only in their receiving mental health or substance abuse treatment services, or both, but also in their being repeatedly incarcerated. These women reported a high rate of substance use as well as impulsive and reckless behaviors, such as driving drunk or physically attacking others (data not presented). Their arrest and incarceration may have been related to behaviors associated with their psychiatric or substance use disorders.

Because we have no detailed information about the characteristics of the mental health and substance abuse services the women used, we do not know why, despite having been in treatment, they continued to exhibit fairly serious mental health problems and to engage in activities that led to arrest and incarceration. One hypothesis suggested by the high prevalence of exposure to trauma among the inmates is that their disorders may be trauma related, and previous treatment may not have addressed traumatic experiences.

An alternative explanation is that, in addition to having mental health and substance use problems, many of these women live in chaotic environments and have poor interpersonal, job, problem-solving, and other skills. Thus mental health or substance abuse treatment services without wraparound services may be of limited benefit, especially if the women return to the environment in which their problems developed. Moreover, we have no data on the amount and quality of treatment. Thus treatment may have been of limited duration or of poor quality, the women may not have adhered to treatment or may have dropped out, or they may have been unable to afford medications that were prescribed. Finally, research suggests that persons with severe drug or alcohol problems may require multiple treatment episodes.

One caveat that must be considered in interpreting the study findings is that the data were collected almost ten years ago. During that interval, the treatment histories of incarcerated women offenders may have changed. The demographic characteristics and proportions of women committing different categories of crime have not changed substantially in that time, which suggests that the characteristics of women inmates have not changed substantially. However, in North Carolina, as in many states, access to and availability of services have decreased in the past ten years (

31). Thus rates of use may have decreased somewhat. Nevertheless, nearly half of the inmates in our study who received mental health services had used inpatient services, which suggests the presence of severe symptoms. Thus many would likely have received some treatment even if services were less available overall.

The high rates of psychiatric disorders found at the time of entrance to prison suggest a need for additional treatment resources for incarcerated women. The law mandates the right to treatment for serious mental health problems (

15). Unfortunately, few services are available to these women at a time when they may be most amenable to change. For example, among women entering prison in Texas, 56.4 percent responded positively when asked if they would be interested in participating in a drug or alcohol treatment program "at this time" (

16). The rapidly increasing rate of incarceration among women—and among men—often means that prison dollars are spent on beds and buildings and not on treatment and other services.

More research is needed to determine how best to address the alcohol, drug, and mental health problems of women inmates. One option might be to provide in-prison treatment that addresses inmates' specific problems and circumstances, including postrelease services. Another option would be to incarcerate fewer women—most are not violent offenders—and use the money saved to provide intensive outpatient treatment services, including wraparound services, that focus on the multiple needs of these women.

Previous studies have demonstrated that substance abuse treatment can reduce rates of criminal offenses and rearrest (

32,

33), and some research has suggested that treatment can also reduce recidivism for some offenders with mental disorders (

34,

35,

36). However, providing services to offenders has generally not been seen as a worthwhile expenditure of public funds, even though such services may have a cost-offset benefit by reducing recidivism and the need for other costly services, such as social and child welfare services, and even though such services may reduce the impact these women's problems have on their lives, their children, and their communities.