Participants and procedures

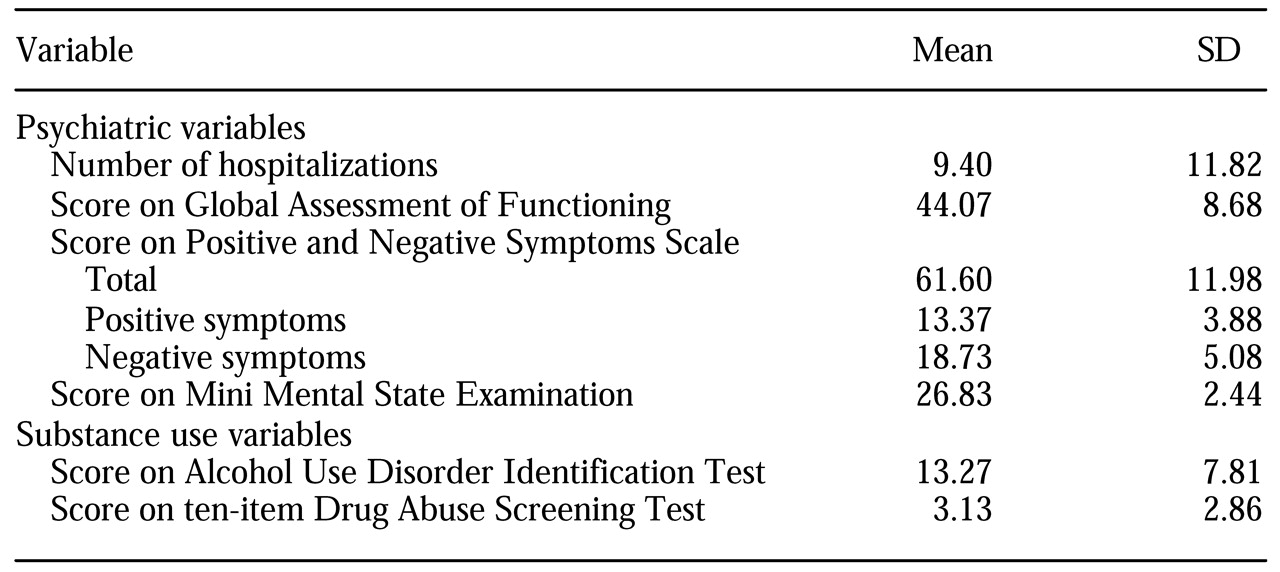

Patients from two hospitals were recruited through referrals from hospital staff. The recruitment criteria were a diagnosis of either a schizophrenia spectrum disorder or bipolar disorder, a current substance use disorder or lifetime substance abuse or dependence as well as problematic substance use during the previous six months, and lack of active engagement in treatment for a substance use disorder. Patients who were judged to be too disorganized or symptomatic to engage in meaningful dialogue were not recruited. A research assistant approached patients at a regularly scheduled appointment, described the project, and invited them to participate. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards of the two hospitals and Syracuse University.

Eligibility was determined on the basis of an interview conducted by a doctoral-level psychologist. The Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) (

20) was used to screen for gross cognitive dysfunction. Possible scores on the MMSE range from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating better functioning. Patients with scores below 24 were excluded, except for one person for whom a lower score was due to a documented learning disability that affects spelling. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (

21) was used to confirm the diagnoses of patients who were eligible to participate. Of the 31 eligible patients identified, 30 agreed to participate. Data collection took place between March 1999 and July 2000.

Several descriptive measures were also used during the screening session: the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) (

22), the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS) (

23), the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) (

24), and the short (ten-item) version of the Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10) (

25). Possible scores on the GAF range from 1 to 100, with higher scores indicating better functioning. Possible scores on the PANSS range from 30 to 210, with higher scores indicating more severe pathology. Possible scores on the AUDIT range from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating more harmful or hazardous alcohol consumption. Possible scores on the DAST-10 range from 1 to 10, with higher scores indicating greater risk of drug abuse. All of these instruments have demonstrated strong psychometric properties in previous research with this population (

26,

27). Patients were paid $10 to participate in this screening session.

Substance use, treatment involvement, and attitudes toward substance use and cessation were assessed before and after the intervention and at three-month follow-up. A research assistant administered all the instruments orally to maximize the quality of the data (

28). During all assessments, patients' breath was analyzed with an AlcoSensor IV (Intoximeters, Inc., St. Louis, Missouri) to maximize the accuracy of reporting. The assessment was rescheduled if the patient's blood alcohol level was above .02. The participant's primary problem substance was the reference point for all attitudinal measures, because readiness to change may vary by substance. Nicotine and caffeine were not considered primary substances, because of their pervasive use in this population (

29). Participants were paid $10 for each of the pre- and postintervention assessments and $15 at the follow-up session.

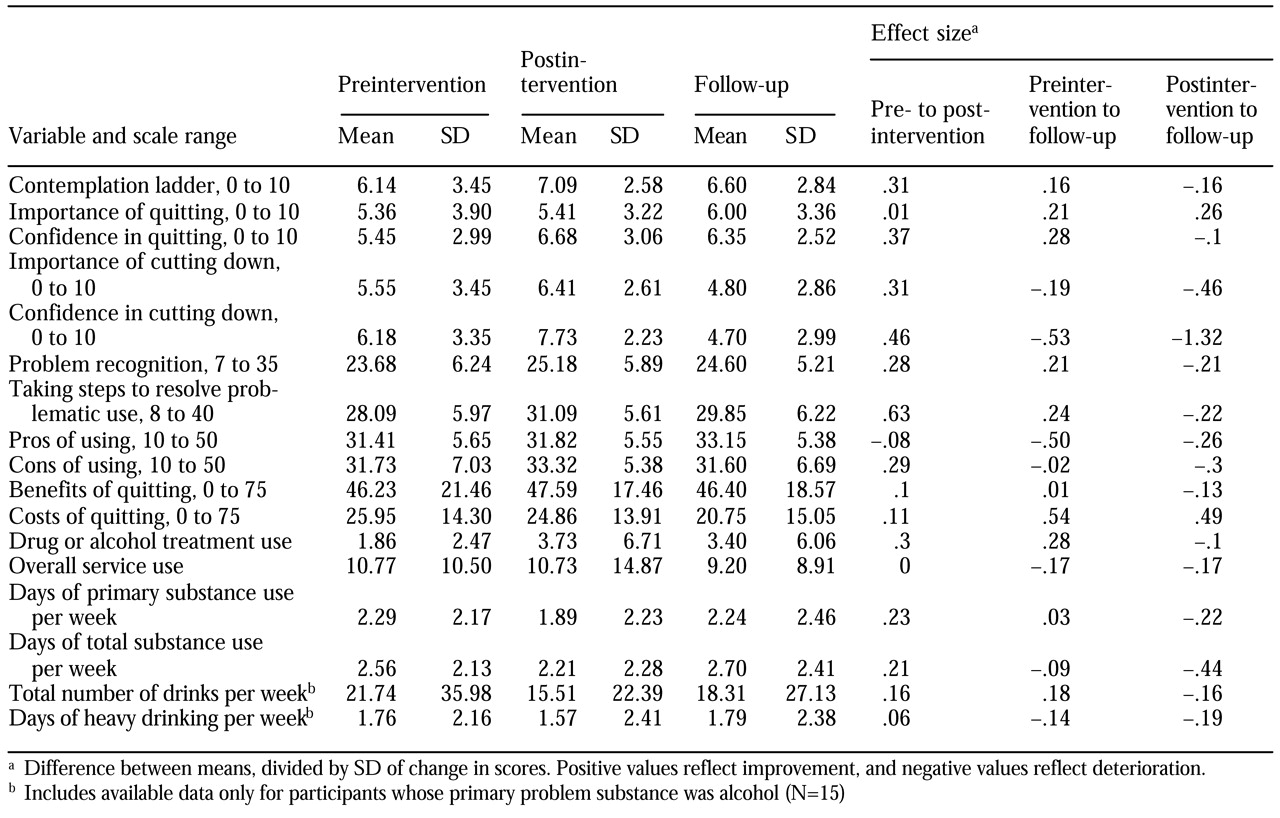

Preintervention assessment. The contemplation ladder (

30) was used as a representation of participants' readiness to change; higher rungs on the ladder represent greater readiness to change. Four expectancy scales were used to assess participants' perceived importance of quitting substance use and of cutting down and their confidence that they could quit or cut down if they decided to (

31).

A stage-of-change algorithm was used to assign patients to one of six stages: precontemplation, during which the person has current substance dependence or abuse and expresses no intention to quit or cut down within six months; contemplation, during which the person intends to change within six months but not within the next month; preparation 1, during which the person intends to change within the month; preparation 2, during which a person in preparation 1 also reports an attempt to quit or cut down in the previous month; action, during which the person says that he or she has quit or cut down within the past six months; and maintenance, during which the person reports change that has been sustained for at least six months. Separate stages were assigned for quitting and cutting down, with the expectation that the latter may be more sensitive to differences among persons with low readiness to change.

Participants then completed a series of self-report scales that measure motivation to change. All the scales have demonstrated reliability and validity with this population (

28). The Stages of Change Readiness and Treatment Eagerness Scale (SOCRATES) (

32) assesses the participant's recognition of a substance use problem and whether he or she is taking steps to resolve the problem. The Decisional Balance Scale (DBS) (unpublished data, King TK, DiClemente CC, 1993) assesses perceived pros and cons of continued substance use. The Alcohol and Drug Consequences Questionnaire (ADCQ) (

33) measures perceived costs and benefits of quitting or cutting down.

Participation in available treatments was also assessed. We adapted the Treatment Services Review (TSR) (

34) to evaluate, for each participant, the number of professional contacts, services provided, and significant discussions that occurred in seven areas: psychiatric problems, alcohol problems, drug problems, medical problems, legal problems, employment problems, and family or social problems. We used a two-week time frame and excluded participation in the research-related intervention sessions from calculations of contacts related to drug or alcohol use.

Substance use was assessed with a 90-day Timeline Followback (TLFB) (

35). Alcohol use was recorded in standard drink units for each of the previous 90 days. Drug use was documented by type of drug. Thus we obtained frequency data for a wide range of substances. Temporal reliability and convergent evidence for the validity of TLFB data are strong (

36,

37).

Three clinician rating scales were completed by primary therapists before the intervention and at the follow-up session, with reference to use of the primary problem substance over the previous 90 days. The Stages of Substance Abuse Treatment Scale (SATS) (

38) is used to categorize a patient's involvement in substance abuse treatment as preengagement, engagement, early persuasion, late persuasion, early active treatment, late active treatment, relapse prevention, or full recovery. The SATS is reliable across raters and over time (

38). Primary therapists also completed the Alcohol Use Scale (AUS) and the Drug Use Scale (DUS) (

39) to indicate the level of a patient's alcohol or drug use over the previous three months on a 5-point scale. The AUS and the DUS are reliable (

39) and valid (

40).

Intervention. The four individual sessions were conducted according to a detailed treatment manual (

4). The intervention was designed to increase recognition of a problem and dissatisfaction with using drugs, interest in quitting, and confidence in the ability to change. Sessions were structured with specific activities and work sheets to help focus participants' attention and record their ideas for later reference. We maintained flexibility in session goals and adjusted the pace when necessary. Catch-up sessions were added when lapses in treatment occurred.

The development of the intervention was guided by three treatment approaches or philosophies. First, the intervention incorporated the five therapeutic principles of motivational interventions (

20): expressing empathy, developing discrepancy, avoiding arguments, "rolling with the resistance," and supporting self-efficacy. Central to the motivational approach is a respect for and support of goals that are important to the patient. These principles promote a client-centered yet directive interventional style that can improve recognition of a problem and motivation to change (

41).

Second, consistent with a harm-reduction philosophy (

42), reductions in substance use that fell short of abstinence were accepted by the therapist. Reduced use is a more proximal goal and may appear more attainable to some patients, especially those who are less ready to change. Third, the transtheoretical model of change (

3) was influential in that more action-oriented procedures—for example, developing an action plan—were emphasized only among participants who were judged to be farther along in the change process, whereas consciousness-raising techniques were emphasized among participants who did not recognize their substance use as problematic.

All sessions were conducted by a clinical psychologist with training in motivational interventions (the fourth author). The first session included feedback on substance use patterns identified by the TLFB, comparison with national patterns, and discussion of the consequences and associated risks. The second session involved a decisional balance activity. Reasons for and against change—for example, "good things about using" and "not-so-good things about using"—were elicited from the patient and discussed. Participants were encouraged to elaborate on change-promoting factors. Change-inhibiting factors presented opportunities for problem solving.

In the third session, one to three personal goals—for example, "to live in a better place"—were discussed in light of the potential impact that cutting down or quitting—as opposed to continuing current use patterns—would have on achieving the goals. In session 3 or 4, expectancies about the importance of and confidence in changing were revisited, which provided an opportunity to reinforce improvements and to address reasons for lack of improvement. In the fourth session, realistic substance-related goals were identified and an action plan was developed that included specific steps, how others may help, and ways to address specific barriers that might arise. The therapist also highlighted themes that emerged during the intervention and reinforced change-oriented talk. All participants continued to receive usual medications and supportive counseling but were paid $5 for expenses associated with attending each 30- to 60-minute session.

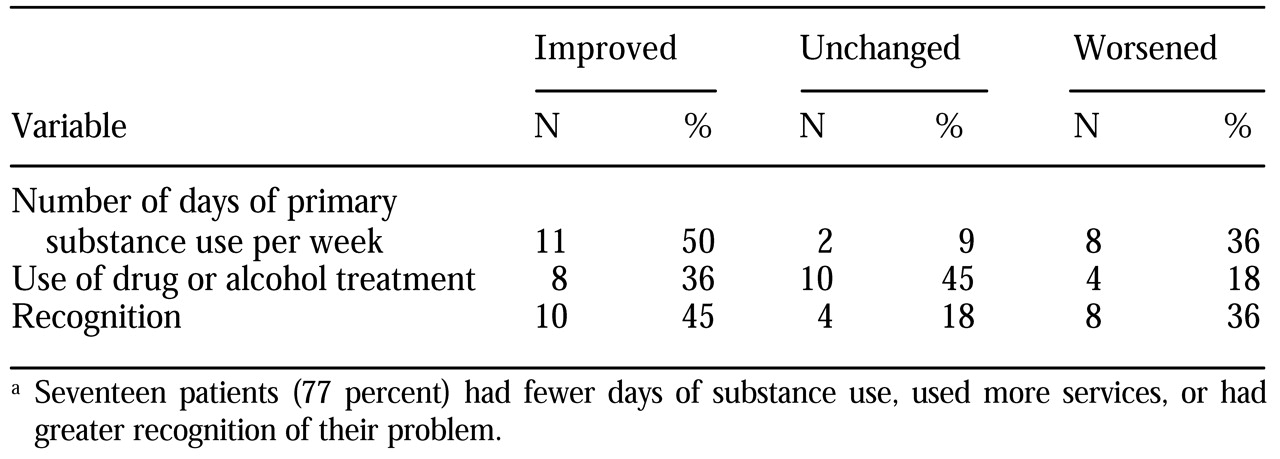

Postintervention assessment. Treatment acceptability ratings were obtained about a week after the last intervention session. For these ratings, seven adjectives were used to describe the intervention—for example, "valuable" or "worthless"—and seven adjectives were used to describe the therapist—for example, "caring" or "uncaring"—on a 7-point Likert scale. Scores for each item were averaged to form summary scores. At that time, all self-report measures that had been administered before the intervention were readministered. The average weekly use from pre- to postintervention assessments was calculated on the basis of participants' TLFB data.

Follow-up assessment. All the preintervention measures were readministered at the three-month follow-up session. Average weekly use between postintervention and follow-up assessments was determined from TLFB data. In addition, a measure of retention of ideas introduced in the intervention was administered. Participants indicated whether each of 20 topics had been discussed in the intervention—for example, "We discussed reasons I might want to quit or cut down." Foils were included to minimize demand characteristics—for example, "We discussed each of the 12 steps."